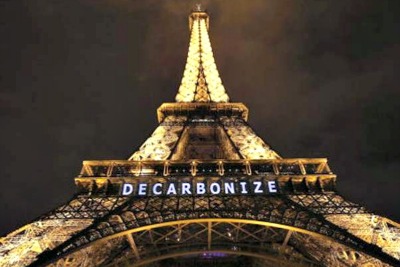

COP21. Success, Disappointments, and the Road Ahead

The resulting Paris Agreement presents a road map for action.

In early December, the world watched as world leaders negotiated the terms and conditions of an agreement that would aim to prevent dangerous climate change. The resulting Paris Agreement presents a road map for action.

In this article, Catherine Devitt, environmental justice officer with the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice highlights some the key successes and disappointments within the Agreement, and argues that challenging times lay ahead in the shift to achieving a low carbon society.

COP21. Success or not?

In the closing day of the Climate Summit, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon shared to the media: “I have been attending many difficult multilateral negotiations, but by any standard, by far, this negotiation is most complicated, most difficult but most important for humanity”. This statement reflects the weight of expectations placed on COP21.

For many, the Paris Agreement was a monumental success, reflecting a universal, explicit acknowledgement among the nations of the world, that climate change is a serious issue requiring urgent action. However, while long on ambition, the Agreement falls short on steps for concrete action.

Key summary points

Where the Agreement succeeds:

• An explicit acknowledgement by 195 countries that climate change is a serious threat

• An overall aim to limit global temperature rise to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels

• Inclusion of a legally binding five year review process of national emission plans, supported by a transparent monitoring system

• Continued and sustained commitment to financing mitigation and adaptation initiatives in developing countries and countries hardest hit by climate change

• The allocation of responsibility to developed nations to “take the lead” on reducing greenhouse gas emissions

• Overall, the Paris Agreement provides the impetus for more ambitious, progressive change

Where the Agreement disappoints:

• The Agreement does not include any reference to leaving fossil fuels in the ground

• No specific date is set for a peak in global greenhouse gas emissions

• The Agreement does not include emissions from global shipping and aviation;

• Vague references are made to technologies and actions which may pave the way for false solutions with potentially harmful social and ecological implications

Photo credit: ewn.co.za

On temperature rise

A recent scientific report found that a 2˚C temperature rise above pre-industrial levels would mean disaster for low-lying coastal regions, and a more sufficient target is required to keep vulnerable populations safe from the effects of climate change (Tschakert, 2015). Therefore, the aim of limiting global warming to 1.5˚C is a welcome outcome. The final text aims to keep warming “well below” 2˚C above preindustrial levels, and to continue all efforts to limit the rise in temperatures to 1.5˚C, representing a much stronger scope for future progress and ambition.

On emission reductions

The critical mechanism for achieving the temperature goal of 1.5˚C requires that each party “shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve.” However, this is where it falls short on action. Currently, the levels of emissions pledged from 186 countries sum up to a 2.7˚C temperature rise, much higher than the 1.5˚C included in the Agreement and higher than the 2˚C limit necessary to mitigate dangerous climate change levels.

Reaching both temperature limits necessitates achieving near zero carbon dioxide emissions by the latter half of the century (United Nations Environment Programme, 2015). The final text sees nations aiming to peak their emissions “as soon as possible”. No specific date is included in the Agreement, although it is recognised that developing nations should peak in their emissions later than developed nations. By way of achieving this, the text vaguely refers to the need “to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half the century.” For some commentators, this translates into achieving net-zero emissions anytime between 2050 and 2100 – meaning that carbon can still be released if balanced by its removal through the means of carbon capture and sequestration (i.e., anything which captures and stores carbon, including biological means such as forests and peat-land, and physical and chemical processes, such as carbon injection).

Five year review cycles

The inclusion of a five year legally binding review cycle allows governments to progressively review levels of ambition. In kick-starting this process, a “facilitative dialogue” will take place in 2018 aimed at taking stock of collective efforts. In 2023, the five year review cycle will commence. While the emission targets themselves within these plans are not legally binding, the final text allows for a transparent monitoring and review process – a major step forward.

In terms of responsibility, developed countries must “continue to take the lead in the reduction of greenhouse gases” and developing countries are encouraged to “enhance their efforts”, moving over time to cut emissions. However, there is no reference to leaving fossil fuel resources in the ground – despite scientific evidence (see McGlade and Ekins, 2015), and climate justice leaders such as Mary Robinson telling us that this needs to be the case if we are to avert dangerous climate change levels.

Allowing for net-zero emissions rather than complete decarbonisation may also open the door to potentially harmful geo-engineering and carbon sequestration techniques. The Agreement is also open to the use of carbon trading mechanisms, despite evidence suggesting that carbon trading in its current form has been ineffective in reducing emissions (see Laing et al., 2013, and Ecojesuit’s report on emissions trading here). Indeed, in his recent encyclical Laudato Si’, even Pope Francis criticizes carbon credits as “an expedient which permits maintaining the excessive consumption of some countries and sectors.” (LS. 171)

Civil society mobilises for action on climate change, during the Paris Summit. Source: Sara Pacia/Inquirer.Net

On loss, damage and finance

The Agreement explicitly directs a task force to “develop recommendations for integrated approaches to avert, minimize and address displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change.” Concepts around liability and compensation (that could result in affected nations seeking redress from big polluters) were excluded from the final text, meaning developed countries cannot be held truly accountable for past or future climate change-related impacts. In fact, the Agreement “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation”, undermining any real commitment to climate justice.

In terms of finance, developed countries must provide financial resources “from a floor of USD 100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries”, although it remains unclear how this will work. This amount will be reviewed in 2025, yet developing countries have argued that this is not enough, and there is no separate target for adaptation finance.

Notably, the figure of US$ 100 billion pales in comparison to the estimated US$ 548 billion spent in 2013 on consumer subsidies for fossil fuel according to the International Energy Agency, clearly showing that considerable scaling up of investment in climate finance is required.

Other sticking points

In the final days of negotiations, important elements around human rights, food security, and climate justice were removed or weakened. Environmental groups honed in on the obvious elephant in the room – the absence of emissions from global shipping and aviation from the final text. Ironically, air travel is afforded to only a small proportion of the global population, yet when combined with shipping, accounts for over 5% of global greenhouse emissions, and is the most climate-intensive form of transport.

The exclusion of international aviation and shipping emissions from the Agreement undermines the 1.5˚C target, and reduces any hope of keeping temperature rise to below 2°C. “Renewable energy” is referred to just once (in relation to achieving access to sustainable energy in Africa), and instead, vague references are made to “technologies” and “actions”, leaving much scope for possible false solutions (with the potential to cause social and ecological harm) to emerge as quick fixes. In addition, the protection and enhancement of ecosystems, which play a crucial role in mitigation and adaptation processes, received only vague attention in the final text.

Hope in a growing social movement

Outside of the Paris Agreement, much hope lies in the climate action movement, which now has considerable reach and is no longer confined to just environmentalists but encompasses a much broader civil society base. This reach may echo the beginnings of the “ecological conversion” Pope Francis calls for in Laudato Si’ (LS. 217). Pope Francis also calls for “a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet… a conversation which includes everyone… a new and universal solidarity” (LS. 14). In going forward, while the Agreement may be weak on certain aspects (some of which are detailed above); it now provides a vehicle in which civil society can hold governments accountable to their promises, bridging any gap between ambition and action. This will certainly be the case in Ireland, where emissions are on the rise, and we are on track to miss our 2020 targets.

A nature-inspired light show was projected onto St. Peter’s Basilica to celebrate the opening of the Holy Year of Mercy, calling attention to the urgency of tackling climate change. Source: (CNS)

The road ahead

The Paris Agreement will take effect from 2020, with challenging times ahead, especially if planned and coordinated steps are not implemented immediately. Despite some of the notable gaps, the Agreement presents a crucial step forward, providing a landing ground for countries like Ireland, to prepare for the shift towards achieving a low carbon society. In looking ahead, the author of this article takes much inspiration and guidance from one commentator. Reflecting on Paris, Charles Eisenstein, the de-growth activist, calls for a “Revolution of Love”, “when we as a society learn to see the planet and everything on it as beings deserving of respect – in their own right and not just for their use to us… then we will realize that as we do to any part of nature, so, inescapably, we do to ourselves… the current climate change narrative is but a first step toward that understanding.”

Author: Catherine Devitt, Environmental Justice Officer, Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice. 21st December 2015

Further reading on climate justice, youth by Fr Peter Walpole SJ can be accessed on the Irish Jesuit Missions website.

References

Laing, T., Sato, M., Grubb, M., & Comberti, C. (2013) ‘Assessing the effectiveness of the EU Emissions Trading System’, No. 106, GRI Working Papers, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment

McGlade, C., & Ekins, P. (2015) ‘The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2oC’, Nature, 517: 187 – 190. doi:10.1038/nature14016

UNEP (2015) The Emissions Gap Report 2015. A UNEP Synthesis Report. Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme

Tschakert, P. (2015) ‘1.5oC of 2oC: a conduit’s view from the science-policy interface at COP20 in Lima, Peru’, Climate Change Response, 2(3). doi: 10.1186/s40665-015-0010-z

Image Eiffel Tower by Patrick Kovarik / Afp / Getty