It is less than two weeks since the Minneapolis police officer, Derek Chauvin, was caught on camera killing George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man. Floyd, who was a father of three, an accomplished sportsman, and a devout Christian had been suspected of passing a counterfeit $20 note.

Protests in the city of Minneapolis have quickly spread across the United States, and the world, with some turning violent. At least a dozen curfews have been imposed in major cities as almost 20,000 National Guard troops have supplemented local police force in a dramatic display of state power. The irony that protests against police brutality have been met with such a show of force cannot be avoided.

It is clear that Floyd’s killing, coming so soon after the shocking murder of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery was just a tipping point for a simmering fury at the rampantly racist behavior of American police, which statistically ends up targeting black flesh almost three times as often as white. Incarceration rates in America far outstrip anywhere else in the world and disproportionately feature African-Americans in ways that warrant it being described in terms of an evolved strategy of enslavement.

We look on aghast from Ireland. We find ourselves marveling at how African-Americans are not perpetually in protest – or outright revolution – at a society so viciously stacked against them. In the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, we recognise that the rallying cry – Black Lives Matter – is not just a political declaration, but a theological one. Informed as we are by liberation theology, we wholeheartedly proclaim that anyone who is a Christian is already committed to this movement, given that on Good Friday a black man was lynched.

While it is important to stand in solidarity with our oppressed neighbours across the Atlantic Ocean, this is also a moment for us to take stock of how our own society is marked by profound prejudice and how our policies of discrimination are built-in to our State. An appropriate comparison has been drawn in protests in Dublin between the Black Lives Matter movement and the system of Direct Provision that we operate.

But the case of the Travelling Community, or Mincéirs, is an even more apt comparison.

The statistics are not as accurate as we would like. That itself might be a policy position, because what is not recorded cannot be reported. After all, if we don’t keep detailed figures about policies that are racist, it is impossible to protest the State’s racism. Recognising that it is difficult to get absolute precision in the numbers, recent research using prison data report that about 5 per cent of the Irish prison population comes from the Travelling Community.

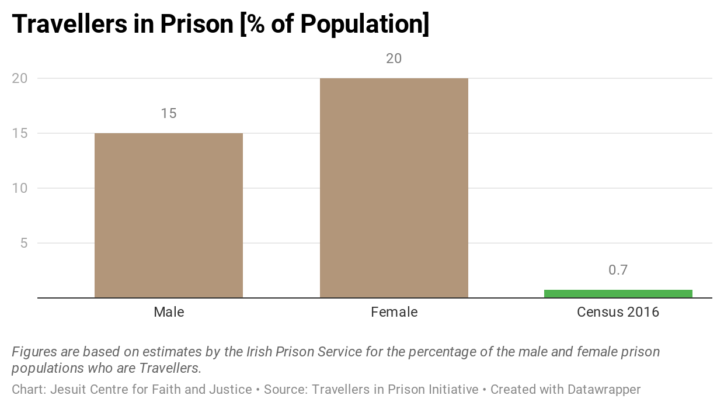

This is almost certainly understated. Travellers tend not to self-identify their ethnicity upon arrival in prison, for fear of active discrimination. The Irish Prison Service informally estimates that about 20 per cent of women in prison are Travellers and about 15 per cent of the male population. In 2017, over half of the population of a single prison – Castlerea – were Travellers.

These figures are put into their correct perspective when we remember that Mincéirs make up 0.7 per cent of the population.

Even working off the weaker official figures, the question is inescapable: Does Ireland have a racist criminal justice system?

From thousands of kilometres away, we can see that the American justice system requires sweeping and profound reform. But let us not sit smugly in a false sense of European superiority. Our own policing, prosecuting, and incarcerating systems are not presently free from systemic prejudice. Irish people only became white in America two generations ago. Just because Travellers have the same skin colour as the dominant culture does not mean that racism is impossible.

If it is prevalent, if it inescapable, then it too requires sweeping and profound reform to resolve.