Last weekend, Irish social media lit up with the sharing of a shocking video. By habit and disposition, I try to avoid clicking on these links. My world is distressing enough as it is at the moment and it is easier to process things when presented in black and white in text. Full colour and in motion provokes sleepless nights.

What is seen in the clumsily shot footage is a group of white teenage boys surrounding a woman who is remonstrating with them on a canal bank before one of the children breaks ranks and intentionally pushes the woman into the water.

The story, as it was later reported, did nothing to reduce the dismay caused by the video. After being accosted with racial slurs on three separate occasions, Xuedan (Shelly) Xiong actively pursued the boys harassing her to tell them their behaviour was unacceptable.

“I told them it was racial discrimination to speak like that. I wasn’t frightened anymore, all I felt was anger. There were lots of lone women walking along the canal at that time but they targeted me. I think there’s a reason behind that.”

Rather than be chastened by her words and her courage, two of the boys assaulted her. As it stands, it appears no one will be brought to justice for this clearly racially motivated attack conducted in broad daylight with eyewitnesses, caught on film. A few days later, two Chinese men were physically assaulted with similar verbal harassment in Cork.

In the aftermath of the remarkable Black Lives Matter protest movement this summer, there has been some serious reflection about the prevalence of racism in Ireland. People of colour in Ireland can quickly puncture any ideas that the old tropes about Irish hospitality, 100,000 welcomes, and our colonial past somehow make us immune to racism. This is not a brand new realisation either. More than two years ago, the Jesuits were highlighting how racism was an unaddressed toxicity at the heart of our society.

The Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice has argued this summer that Ireland’s criminal justice system is functionally racist. The facts are beyond dispute: we criminalise the Travelling community disproportionately and we in the time since data has emerged to support anecdotal hunches about day-to-day bias in our policing forces.

The social imagination in which the Irish State was established was ethnically homogenous. People of my generation – I still pass for “young” in certain quarters – can often recall the first time they met someone who was not Caucasian. The transformation in Irish demographics over the last generation has been significant and it is important to note that immigration has been warmly welcomed – from both sides – in many instances. This week the CSO published figures that unpack some of the recent trends, which include a positive net migration rate (meaning more Irish people returned home than left) as well as continued immigration.

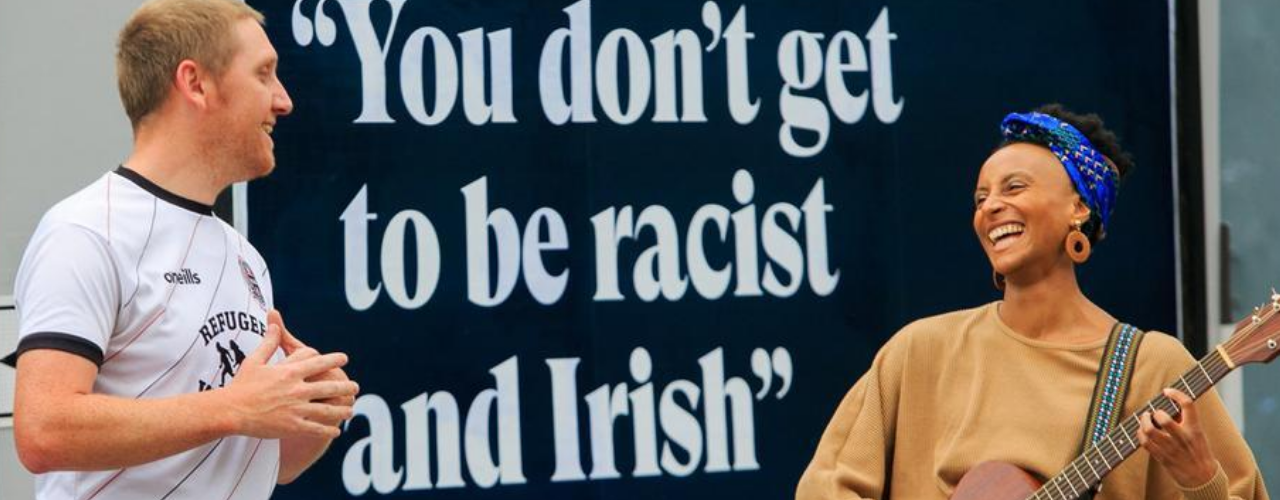

How Ireland deals with the problem of racism is yet to be resolved. We might hope that the default-ethnostate conceptions of the last century are bankrupt, but the emergence of nationalist populisms around the globe would not support that. One approach being tried might be described as “top-down reformation”. An example of that is a recent billboard campaign featuring poetry by the pop singer Imelda May, which reads: “You don’t get to be racist and Irish.”

While the good intentions behind the statement can’t be denied, the poetic weight might be questioned and the sheer facticity of the claim – either in law or in the philosophy of what it means to be a republic – is risible. When we trace the source of this campaign, we find it is supported by an NGO called Rethink Ireland, which seeks to “work with bold, courageous and compassionate leaders who seek to invest in change.” That their support comes from the Bank of America, State Street, Twitter, Zurich, and various other corporate behemoths might mean they are not a wise investment if you hope their campaigns will successfully reduce the rising tide of racism in our society, never mind head off the risk of an ethno-nationalist populism.

There are moves afoot to introduce hate crime legislation, which is another approach to the problem. Supported by groups like the Irish Network Against Racism, this move would have the benefit of not just addressing racism, but laying a legal foundation for opposing all kinds of hate-motivated acts of violence, whether addressed to belief, sexuality, ethnicity, or otherwise.

Discerning whether this is will be an effective response is beyond the capacity of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, but in recent weeks we encountered one sizeable argument against this approach. In her latest collection of essays, the British novelist and intellectual, Zadie Smith, wonders whether the adjective ‘hate’ adds anything to the noun ‘crime’. She writes:

“I find it hard to distinguish between forms of hate that have the same consequence. The hatred of women versus the hatred of this particular woman. The statement The police are investigating this as a hate crime always prompts in me the query: when it comes to murder, what other kind of crime is there? I realise that’s banal but I can’t help it. I think what I resent is not the recognition of a murderer’s motivation – which should never be obscured – but an elevation of importance in what strikes me as the wrong direction. To think of a hate crime as the most uniquely heinous of crimes seems to lend it, in my mind, an undeserved aura of power.”

Smith neither constructs this argument as, nor intends it to be, a knock-down defeater of the idea of hate crime legislation. But the question she asks presses on a weak point of the proposal. Casting hate in terms of crime flatters the one who hates, embellishing their violence with the status of an ideology.

Questions of race have been a consistent focus of some of the richest theological research done around the world in recent years. Even people who have no connection to Christianity and little feeling for the faith would be wise to consult this literature if they are interested in understanding how racism works. Works like Willie Jennings’ The Christian Imagination, James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree, and J. Kameron Carter’s Race: A Theological Account interrogate the ways in which concepts of what it means to be white or American or Christian have been deployed to ruin the lives of people with darker skin. Theologians have a store of language about ideas like human dignity which allows a thorough interrogation of racism, especially when the systemic injustice is interwoven with communal religious belief.

But when we look to the Irish church, there is largely silence on the question of race, ethnicity, and national identity. This is all the more scandalous because Christian congregations on Sunday are commonly one of the most diverse and well-integrated parts of our society. Apart from notable exceptions like Gladys Ganiel in Belfast and Siobhan Garrigan in Dublin, there are few theologians or Christian academics interrogating what it means to be Irish. This is a surprising oversight, since ethnic integration is at the heart of the Christian Gospel, which is a message brought to this country by a Roman from Wales. What it means to be Irish is the presenting issue but sitting below that is the question of what it means to be human.

Hate crime legislation might be an essential aspect of our push-back against a growing tolerance of racial intolerance. If mediocre poetry on billboards actually helps, plaster those quotations in every town and village! But the people of Ireland need to reflect seriously on how their own sense of belonging excludes.

Our society needs to ask awkward self-critical questions about how our rhetoric of inclusion leaves certain communities excluded. And there is a theological project to be undertaken which interrogates how the stories we are telling ourselves about how we got to where we are encourages the kind of violence and harassment we are seeing.