Policy-making is, in essence, about telling stories. Politicians, civil servants, think-tanks, and advocacy groups may like to imagine we have, at least, moved beyond stories and tales to ‘data’ and ‘evidence-based policy.’ Yet, the stories we tell each other change how we perceive our reality, affect our sense of agency, and shape the responses possible. Stories are underestimated in their role in shaping our political imaginations.

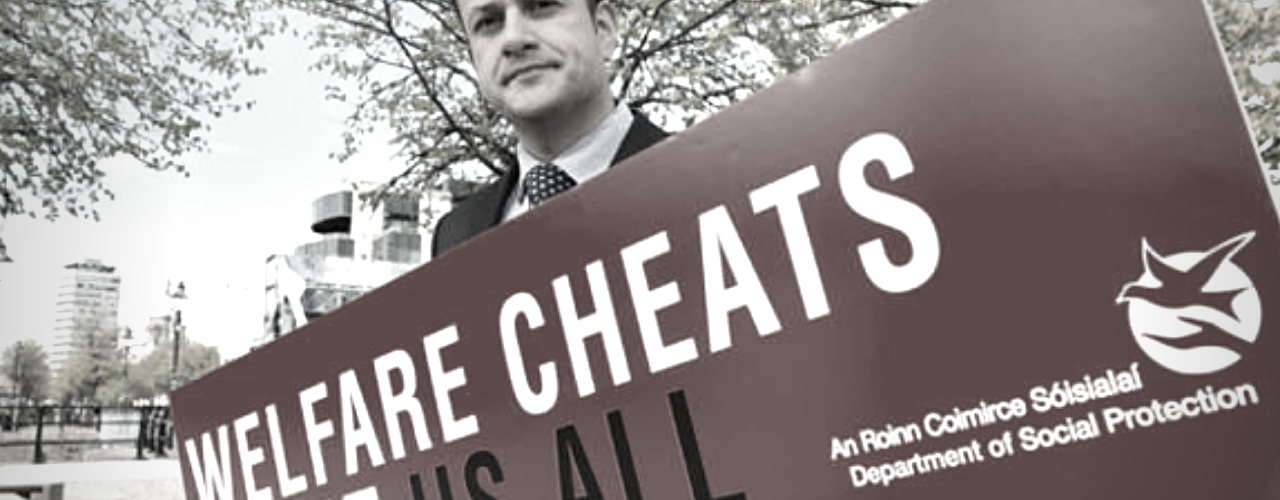

Stories are typically based around a common problem, with the characters taking on the role of fixers (heroes), causes (villians) or the harmed (victims), moving towards a resolution. The infamous Welfare Cheats Cheat Us All campaign, launched by Leo Varadkar back in 2017, utilised the power of storytelling in an extremely effective way. He cast himself as the hero in the story. Those claiming welfare fraudently were the villains and anyone claiming income support payment became suspects in the narrative. We – that gloriously mythic we – the unsuspecting public, were the victims. But we could also play supporting roles to the heroes in this piece. Shortly after, department officials moved to distance themselves from the campaign as the level of fraud was wildly overstated and the sums recouped were meagre.

So, why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

Many other examples exist of similar stories – here and here – being told in the politicial and public sphere. If we understand stories as shaping our imaginations and actions, then the stories which we tell have consequences. Lone parent policies exacerbated their poverty and the relentless pursuit of reduced budgetary deficits delayed economic recovery but the policies gained traction through their accompanying story.

I want to suggest that policymaking is not born out of rationality or data but the story or narrative which accompanies the policy. And, at its heart, policymaking is not about contested data, where the most reasoned data wins out, but contested stories. Recent homelessness data and policy may provide a small window for us into this idea of policymaking as contested stories.

In July 2019, following the number of homeless adults and children surpassing the evocative threshold of 10,000 in February that year, the Department of Housing, Planning & Local Government (hereafter the Department) began to publish Quarterly Progress Reports alongside their already monthly homelessness data. The information was more extensive as it presented and interpreted data and trends on the number of families presenting as homeless, prevention of homelessness, numbers leaving emergency accommodation, and duration of stay. As we currently have two years worth of progress reports, it is worth revisiting this additional data to see what story was told and whether other stories exist.

To set the broad context of homelessness over the past two years, 9,753 adults and children were officially recorded as homeless in December 2018. This rose to 10,514 in October 2019, remaining at over 10,000 for twelve months and gradually decreasing to 8,200 adults and children at the end of December 2020. The largest fall in homeless numbers coincided with the period of the first Covid-19 lockdown and ban on evictions as numbers declined by over 1,000 people between March and May 2020.

Each quarter, using the numbers of those who left homelessness, the Department compared the numbers exiting with the corresponding quarter from the previous year e.g 2019Q4 was compared with 2018Q4 and so on. The first four reports demonstrated a double-digit increase in exits from homelessness. People were finally leaving homelessness to secure tenancies in large numbers. A breakthrough had been made. We just had to stay the course.

Yet when we look at the absolute numbers of exits from homelessness over the two year period, it is difficult to fathom the existence of double-digit increases. Comparing each quarter with the previous quarter in 2018—which had a much lower base for exits at a time when homeless figures were rising rapidly—allowed the production of ostensibly higher rates of increase. This method would have merit if applied consistently through reports. As we can see from graph, the variance in numbers was low, only 232.

As the number of quarterly exits began to decline, the Department did not report the 4.3% increase in 2020Q2 or the -13.7% in 2020Q3. Instead, they altered their reporting method and based the change on the corresponding six- and nine-month period in 2019 so the reported change would be a 7% and 0.3% increase respectively. The story changed. So, in essence, during a quarter when exits from homelessness decreased by 81, the Department could report an increase in 7% while a quarter with a decrease of 115 exits could be reported as a 0.3% increase. We see the claim data is the hard, objective material of fact is also a story. The numbers don’t shape the story. The story selects the numbers.

When the method of presenting homelessness exits based on comparison with the previous quarter is applied, a different story emerges. Granting that things have been difficult for everyone since the start of the pandemic, the fact remains that the double-digit headline figures reported in the first four progress reports appear misleading. When the quarterly figures are compared with the previous quarter, we see more modest increases of 1.6%, 9.8% and 1.2% and, in fact, a decrease of 1%.

With homelessness remaining over 10,000 up to early 2020 – despite the claims of significantly increased exits from homelessness – the idea was reinforced that homelessness was an intransigent problem. In other words, it was not the fault of the Department. The small quarterly increases demonstrate that neither of these ideas were true.

Since homeless figures started to be published, only rarely has the Department interpreted data compared with a corresponding period from twelve month previous. As homeless numbers increased steadily over 10,000 adults and children in 2019, this would have made little sense from a political perspective as the increases would have been even starker. Yet, in response to continued failure in ending homelessness and increased public pressure, more resourceful methods of interpreting the data to tell a more palatable story were found.

The Department’s story of exits from homelessness was of a rapid and sustained increase in the numbers leaving homelessness at a time when the overall homeless numbers were increasing. Looking at the data in a different light, the exits from homelessness were modest, plateauing quickly, and presented in a manner to suggest a definitive turning point in the enduring legacy of homelessness under successive governments. Maybe, if certain key indicators are not telling the proper story, new indicators can be found.

Eviction bans and the sudden availability of short-term tourist lets have made it difficult to surmise what is the result of Government policy or the natural consequences of social restrictions and reduced travel during a pandemic. When normality resumes, the homeless figures will immediately provide a key indicator of whether policy changes will have long-lasting effects or were merely the knock-on effects of other policy.

If we understand the stories we tell each other as shaping our political imaginations and actions, there is a profound short-sightedness in telling stories of success in the face of enduring human suffering. Considering the narratival angle to policy can induce a certain dizzyness. If facts are shaped by the stories we are telling, where can truth be found? The JCFJ is committed to an ancient practice of approaching such questions from the perspective of the people on the underside of these systems. In our blog next week, we hope to explore that more perspective more fully…