For most of us, time is money. Quite literally. We live in a society where the majority of people exchange their waking hours for payment we call wages, so as to provide for the essentials of life and, if are fortunate, a few occasional luxuries.

It is curious that for all the time we spend preparing to get a job, getting to our jobs, actually at our jobs… we spend relatively little time thinking about the entire arrangement.

We’ve got better things to do, I suppose. Like spending the wages we earned at our job. Or, as is increasingly common, working a second job because the wages from the first job don’t cover our costs.

I have been thinking about the system of wage labour in which we live ever since encountering the Just Wage Initiative from the University of Notre Dame. Informed by experts from a range of disciplines and informed by Catholic Social teaching, this initiative questions the foundational question – what makes a wage just. Of course, there are important voices who would declare this question bogus. Marx famously argued that profit was the surplus value of the laborer unjustly appropriated by the capital-holding class. Wages, in that view, are just that share of your toil that the bosses think they can get away with giving you.

Christians can find plenty of scenes in the Scriptures where this kind of class antagonism seems to find resonance. While Jesus’ teaching grants the existence of wages and articulates that workers must get paid rightly (Luke 10), his parables often unveil a logic which seems to entirely undermine the idea that your access to the goods of life should be reliant on your toil (Matthew 20). This makes sense, even to the most market-convinced of readers when we remember that we do not expect children, the elderly, or those with profound disabilities to earn their keep. We may disagree about the details, but we still live in a culture with a shared principled commitment to using our wealth to care for the vulnerable among us.

The Just Wage Initiative is a useful device for thinking more rigorously about what is clearly a complex area. They establish seven criteria by which we can interpret the justice of a wage:

- Just wages enable a decent living for the worker and their household;

- Just wages enable asset-building;

- Just wages include basic security services;

- Just wages are not discriminatory;

- Just wages are determined in part by the worker;

- Just wages distinguishes differences between types of work and workers;

- (And most unusually they state) Just wages are not excessive.

This represents an interesting framework, beyond brute calculations, that would help people think ethically about payment. They index their principles against historic Christian thought and social scientific research. By assessing a wage from these perspectives, they argue, it is possible to establish how morally sustainable a particular payment approach might be.

In Ireland we do not have a tradition of thinking in terms of a just wage. Even a “minimum wage” was a relatively recent advance. And while there is much discussion today about “living wages“, our support payments do not map on to real-world numbers so it is hard to tell small and medium enterprises that they have to meet a standard the State dodges. While Irish society satisfies some of the Notre Dame criteria quite easily, there are other areas in which we lag far behind satisfactory levels. The idea of excessive wages is very popular with the electorate but consistently resisted by decision makers. Ireland, famously, has some of the highest paid public servants in the Western world. And some industries claim that they can’t even recruit people anymore because we have salary caps installed (after, let us not forget, those industries played a central role in almost bankrupting the State).

But the area where we really fall down is when we test whether Irish wages can enable asset building. While salaries are relatively high, for most people, they are not sufficient to buy a house, which is the primary mode of asset accumulation available to those who are not very rich. In fact, what we are finding more and more is that the people who are being made homeless are also people who are working plenty of hours and earning good wages. It is not just that asset accumulation is out of reach, a secure roof above their heads feels impossible.

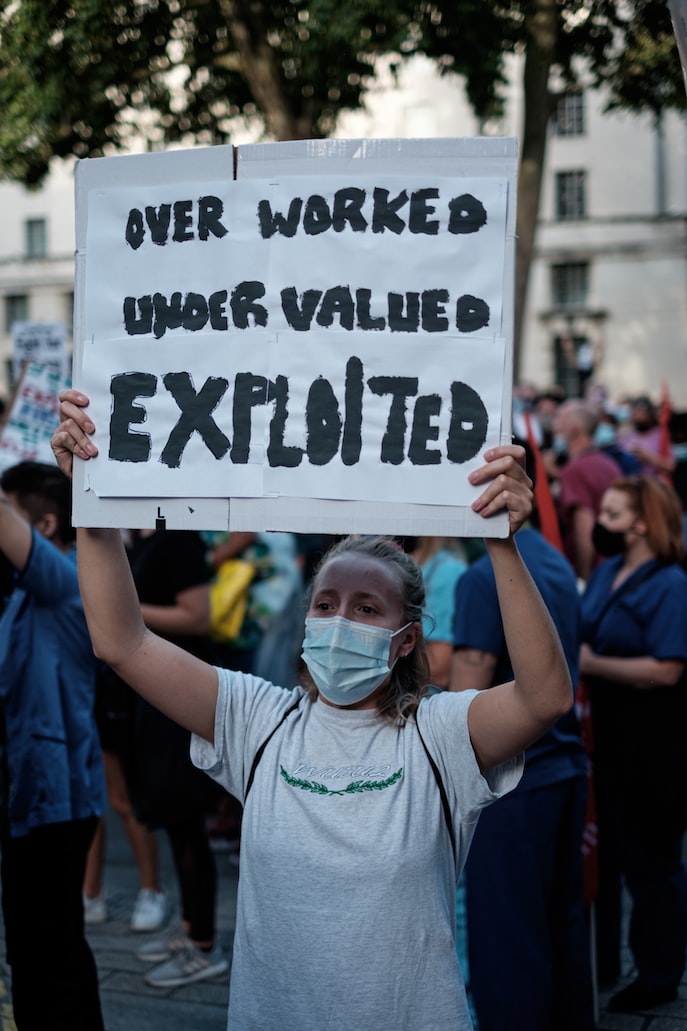

Time is money, and the longer the Irish government avoids the obvious step of committing to large-scale building of public housing on public land for the public good, the faster those homelessness numbers will rise. It seems that for many, it doesn’t matter how much wages they earn, rent will still accelerate out of their reach. Such a society can be described in many ways but the words that come to mind are not positive: absurd, irrational, and, in the end, unjust.