This weekend marks Prisoners’ Sunday, a moment in the year prompting us to pause and consider the men, women, and children who inhabit our prisons and places of detention. People in prison are rarely the recipients of sympathy. Their concerns and travails barely register with the general public. In fact, public opinion on penal matters often seems to favour longer, harsher sentences. Despite Christian directives on themes of forgiveness, redemption, and love for all of humanity, even the church-going population are largely ambivalent. The recent synodal process, a collective deliberation about issues that are important to ordinary Irish Catholics, did not stir enough concern for the plight of prisoners and their families to warrant a mention. In any case, the fostering of sympathy may not be enough, for those in prison, or for ourselves either.

Sympathy with Suffering not Thought

The destitution he observed around him in late Victorian Britain spurred Oscar Wilde to write The Soul of Man under Socialism, in which he states that “the emotions of man are stirred more quickly than man’s intelligence … it is much more easy to have sympathy with suffering than it is to have sympathy with thought.”

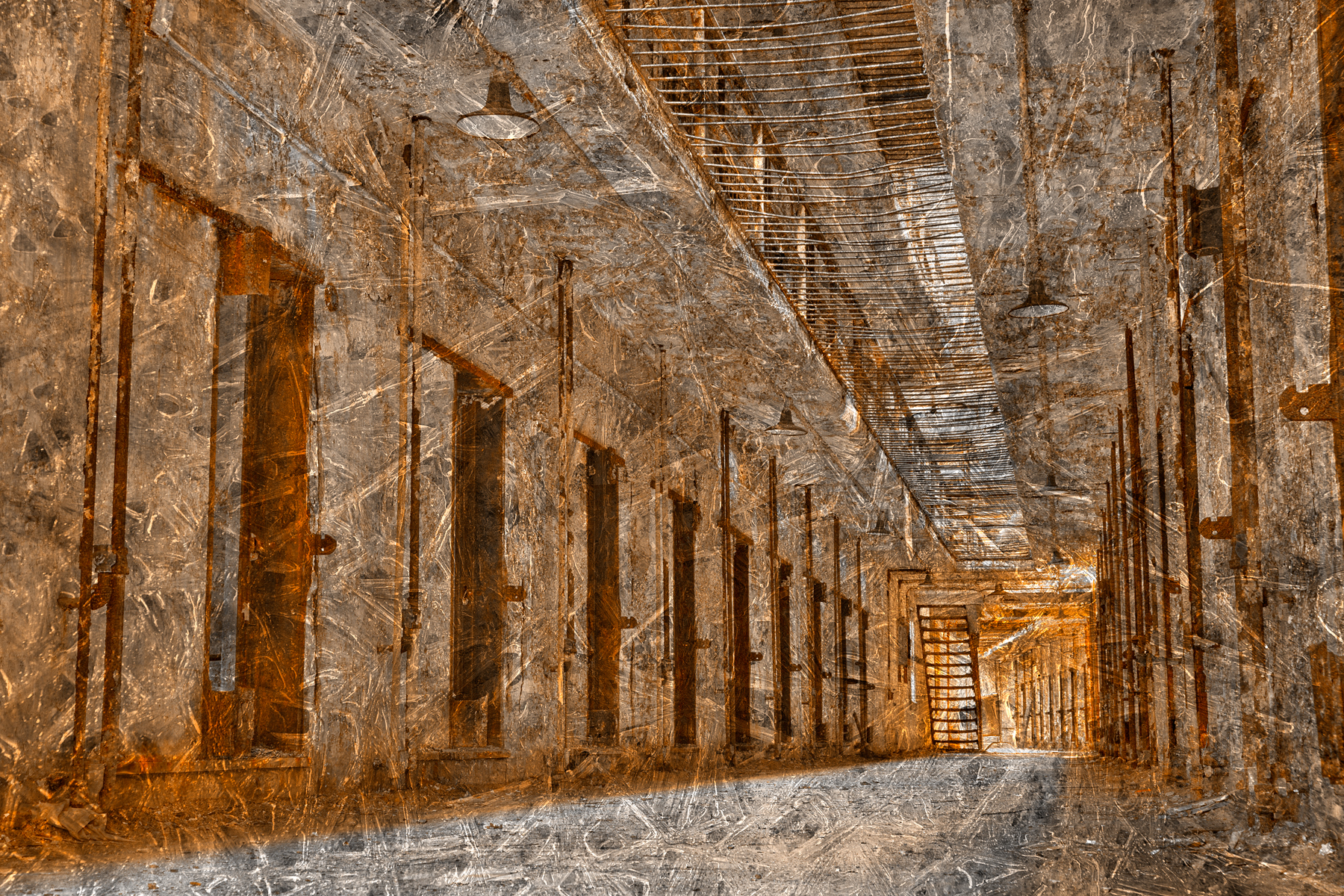

To walk the wing of a women’s prison in Ireland or to spend time in the communal spaces is to be in proximity to women who frequently have suffered great hardship. Their stories feature homelessness, addiction, mental and physical abuse, and severed familial relationships. Somewhat perversely, some are in prison as a result of a misplaced compassion. Concerned judges sometimes issue custodial sentences for women with particularly chaotic lives. Two media stories this year framed such decisions as acts of benevolence. The first tale was of a woman who was living in a tent, and found succour in prison; the second narrative told of a woman with severe mental ill-health on trial for breaching a safety order, whose solicitor agreed with the judge that a prison sentence would be the “lesser of two evils.”

Sympathy without thought has led us to this place, where women are sent to prison guilty only of being homeless, mental illness, or a substance addiction.

Prison is an institution where we should never forego thought. The political justification for prison is that it is necessary, to keep people safe from those who pose a threat to their safety. Prisons are believed to serve four additional purposes: deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and the delivery of justice. There are other aims but these are the main points. The irony is that these agreed purposes have endured, yet no definitive evidence exists that prisons effectively fulfil any of them.

Prison as Shelter

But if we consider the list of purposes in light of the typical female prisoner, questions about their relevance remain. Where is the threat to public safety that requires the removal of traumatised women from society? Is the aim of imprisoning women to deter others from crimes caused by severe mental ill-health, substance abuse, or homelessness? Or should we understand their sentences as punishment? As we consider the options, are we just left with the perverse situation where the State is punishing individuals for its own failure in social provision?

As is common, the answer is more banal. We are really only left with one move which is logically coherent; the creation of another purpose of imprisonment: the provision of shelter. Some women in our prisons are not criminals, yet they find themselves in prison for the absence of healthcare and a secure home. Many of those who are convicted in prison, are there for petty, victimless crimes.

What we are currently experiencing is a mission creep—the gradual expansion of prison beyond its original aims or goals— which is very difficult to row back once it becomes ingrained, especially in rigid institutions of detention. It is important to state that this is not a mission creep desired by the Irish Prison Service, it is the result of policy failures in housing, addiction services, and mental health services. At the moment, it is easier to envision the Irish State providing more prison places instead of providing the homes, addiction services, and in-patient care that are desperately needed.

Why them and not me?

Pope Francis’ teaching and ministry has brought prisoners and their plight to the centre of his pontificate. His visits to prisons are a radical expression of solidarity with the people they contain. In 2014, he described the experience of witnessing the people who inhabit prisons he visited, asking “why him and not me? I feel this way. It’s a mystery. But beginning with this feeling, with this feeling I accompany you.”

Human lives are fragile and can be easily derailed. This Prisoners’ Sunday, we should begin to cultivate the necessary interconnection between our emotions and our intellect, between sympathy and thought, and move towards a radical solidarity with the men, women and children who – often because of circumstances over which they had no control – ended up in our penal institutions. Let’s ask ourselves why them and not me?