Dublin city centre is unusually congested. It is estimated that the extent of traffic in the capital costs hundreds of millions of euros a year in lost productivity. For these very practical reasons, the city council has committed to a new transport plan. Initially will involve a couple of hundred metres of bus gates and the closing off of a few left-hand turns. Although it was fully consulted and 80% of the almost 4,000 submissions supported the plan, which was then voted on after thorough debate in the city council, there are last minute efforts by vested interests to block it.

The plan aims to ease congestion and increase the possibility for more active transport solutions between the canals.

What does this look like?

Well, from the vast network of sensors within the city, the Council can conclude that as much as 60% of the motor traffic in the city’s centre is passing through – the drivers are actually going elsewhere. The plan isn’t anti-car; it isn’t a far-fetched ideological fantasy of some radical cyclists. It’s a project intended to re-route this batch of traffic around the city to free up the core of our capital for more liveable and workable spaces. The high-quality planning has engaged with thousands of citizens and stakeholders and been given democratic mandate by the city council.

This is a very modest plan. We are not following the leading example of cities like Ghent or Paris. It will speed up buses, it will improve air quality, it will make the city safer to cycle in, and a more pleasant place to be. It is a live plan and can be adapted as it rolls out.

But now some car park proprietors, aided and abetted by a junior minister, are trying to block the improvement of the city.

Clearly this is an anti-democratic attempt to skewer a plan that aims to serve the common good because some individuals feel it threatens their private profit. But it is also depressingly predictable. For decades, every single move to limit private motorists from slowing down the city has faced massive opposition.

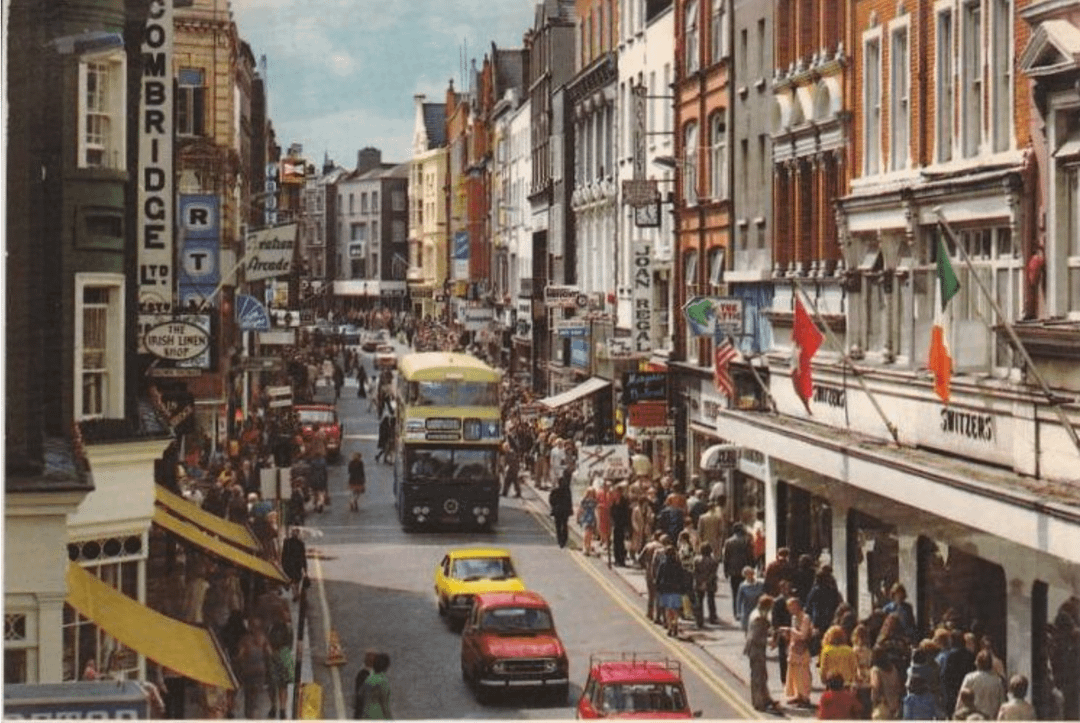

Today, one of the most iconic images associated with our city is pedestrianised Grafton Street. But the process that achieved the removal of cars from that avenue was torturous and longwinded. The Irish Times reported on December 4th, 1987 that it “was a long, slow process bedevilled by every objection imaginable, and a few more besides.” More recently, the hugely successful pedestrianisation of Capel Street was opposed, by the same people who are promising that the modest changes of the Dublin transport plan will bring chaos. The much smaller scale project to pedestrianise Liffey Street – which even before any modifications had more than three times as many pedestrians as cars – was also opposed by the usual suspects. The cycle lanes installed along the quays – compared to amputating a limb from the city!

But the opposition is also there for largescale projects too. The DART is an essential cog in Dublin’s machinery and a beloved part of the city’s fabric. Back when it was being built, confident men aligned with business interests were asserting that it would never succeed.

The LUAS is perhaps even more loved – and the subject of many affectionate memes from the citizens of the city – but for the longest time it was derided as a pointless white elephant. “LUAS lunacy” was a catchphrase of the country’s best-selling broadsheet newspaper at the time of its construction.

Even the Dublin metro is opposed by some people. At present, Dublin is unique among European capitals for not having a train link from its airport to the city and instead relies on taxis, easily delayed buses, and private motor cars to ferry people to and fro from the terminals.

There are a record number of people taking public transport into the city – three in every four visitors arrives by bus, tram, train, bike or on foot. Only 24% of consumers drive! This is the reality before Bus Connects is properly active, before a coherent safe cycling network has been built, before the Metro has even begun!

The reality is that a small number of people are using their corporate power to exert an out-sized influence on the city. Even if they were right, this would be the wrong way to go about things. But just as they were in the wrong about pedestrianisation and the DART, the LUAS and the metro, they are wrong about this.

The city will flourish now and into the future to the extent that we adapt to more sustainable solutions. There is a long history of self-interested voices drowning out the common good in this city. It’s time for this plan to be delivered.