Introduction

Forced to take an indirect route to work or a night out because of “no-go” streets. Hurriedly crossing the road due to serial law-breaking and aggressive behaviour. Speeding up on your bicycle as a “single male” aggressively follows. Children unable to go to school on their own—even the shortest distance—without needing to be delivered to the school gate in the parental car. The need to have protective equipment so as not to be the victim. Ireland’s cities and towns are indeed becoming more dangerous.

Recent pronouncements by politicians and celebrities on Ireland’s streets are correct but not for their intended, and often coded, reasons. Driver violence is endemic, with no end in sight but the equivalent of official thoughts and prayers.

Driver Violence

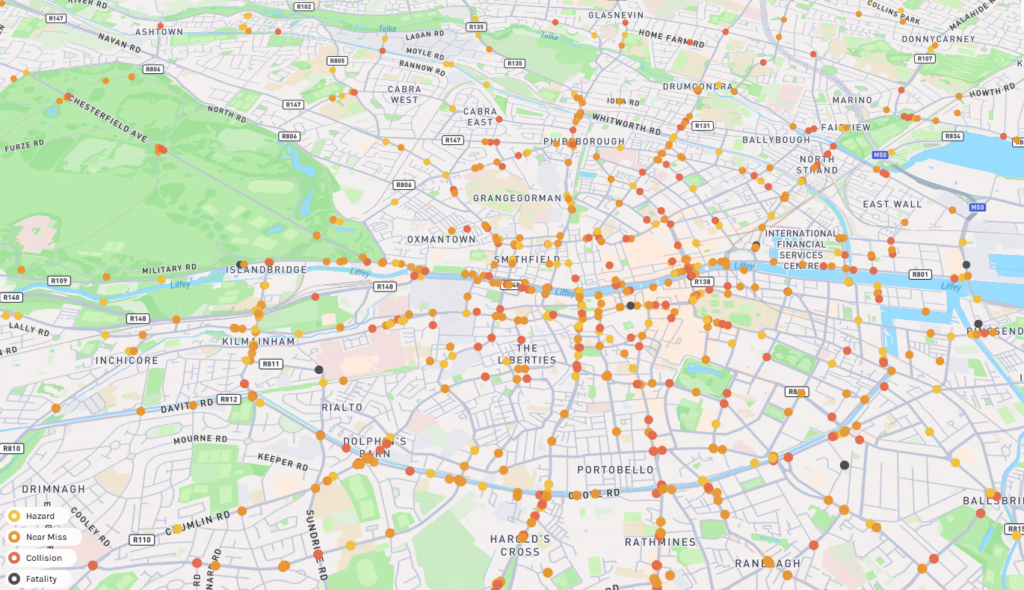

A quick glance of the Dublin Inquirer’s Collision Tracker (which you should fill in) for inner-city Dublin indicates the frequency of fatalities, injuries, and near misses as adults and children go about their daily lives to work, education and play. No village or postcode emerges unscathed. Many of the heavily coloured junctions we will recognise and can recount our own tale of a near-miss or inexplicable driver conduct.

Screengrab of Dublin Inquirer Collision Tracker (23rd March 2025)

In 2023, the number of people killed on our roads was 184, the highest in almost a decade. Compared with 2021, with 137 deaths, this represented an increase of 34% in only two years. And, of the 178 people who were killed on our roads last year, 39 were pedestrians, 11 were cyclists, and 4 were e-scooter users. To pause for a moment and consider that 54 people were killed using active transport last year, while no national emergency plan was implemented, is to realise that these deaths are factored in as the cost of a car-centric culture, where no impediment to driver convenience will be tolerated.

Deaths alone do not adequately convey the social harm and lasting physical and psychological scars suffered by victims of road violence. Considering the most vulnerable road users—pedestrians and cyclists—the official number of recorded injuries was 2,250 in 2022, 50% higher than a decade previously in 2013.

Official numbers on injuries suffered by people who walk or cycle is limited due to time delay and recording discrepancies. Recent reports have highlighted serious under-reporting of injuries caused by drivers. For example, after an examination of hospital data, it was discovered that the number of children injured while cycling is six times higher than official An Garda Síochána records. Children often heal quickly but there is social harm caused which lasts a lifetime as they grow and develop in environments where their independence and play is severely curtailed for the sake of motorists (and their freedoms). This is most sharply experienced in the (often-poor) neighbourhoods in Dublin where their streets function solely as through-roads across the city.

The 2023 Child Casualties Report revealed that two of every three children killed or seriously injured on Irish roads from 2014 to 2022 were walking or cycling. Furthermore, and most shockingly, two thirds of child casualties were injured on urban roads with a speed limit of less than 60 km/h. Early evaluation of the Welsh government’s introduction of 20mph (32 km/h) speed limits suggests that 100 fewer people were killed or seriously injured in the first year of implementation.

Decreasing Crime Rates

Even dismissing the agenda of proponents of “lawlessness” discourse against particular groups of people—whether asylum seekers or teenage boys—it is worth noting the shaky ground that they are standing on. Over the 12 months from mid-2023 to mid-2024, assaults causing harm, robbery from person, and possession of drugs for sale all decreased. These are the offenses that most people would probably list as resulting in the perception of dangerous streets and towns.

The offences on the rise—theft and disorderly conduct—are those related to addiction, poverty, desperation, and need. But, like driver violence, these are much less sexy and attention-grabbing, requiring community investment rather than more prisons and police.

Response of Policymakers

Faced with rising road deaths, increasing driver violence against pedestrians and cyclists, and falling crime rates in many areas, what will official Ireland do? Quicker than an SUV driver through a morning rat-run beside a primary school, one of the new FF/FG(Ind) coalition’s first decisions on assuming power was to rollback on their previous commitment to maintain a 2:1 spending ratio on public and active transport over road projects for motorists. Close on their heels, Dublin City Council then announced that funding for cycle lane construction and other active transport project in Dublin would be cut by €16million for 2025.

Politicians and policymakers, with even the faintest commitment to so-called “evidence-based policy,” would see the modest expenditure and (painfully slow) progress on safe infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists as warranted to reduce the deaths and injuries on our roads. Instead they roll over for car industry lobbyists and the “motonormativity” which prevails in Irish society, rather than providing leadership and a map to a future with less road violence, death, and injury to all road users.