Dr. Tony Bates

Introduction

When ‘Deirdre’ arrived to see me with her mother, my first impression was of a young woman with a warm smile and not a problem in the world. She was twenty-three years old, already the mother of two. As she checked out my office, I wondered if she was happy to be here. I was concerned that coming to see me might have been more her mum’s idea than her own. In confirming the appointment, her mother had described her as ‘a bit lost’, ‘having lots of panic attacks’, and ‘stuck in a relationship that’s not doing her any good’. But none of this was apparent in those opening minutes of our meeting.

Deirdre assured me our meeting was her choice. She added that even though she might appear relaxed, she was anything but. She had been nervous about coming to see someone because she didn’t find it at all easy to talk about ‘personal things’. She remained cautious at first, sat slightly hunched in the chair avoiding eye contact as if to protect herself. Gradually, Deirdre opened up. And before long, her words flowed. She barely paused for a breath, as if pausing at all would risk her shutting down completely. Deirdre was determined to tell her story, to release what had been pent up inside her for a long time.

Deirdre described in detail her experience of living with a jealous man who had intimidated and threatened her for the past three years. She cried. She had been afraid to tell anyone – especially her mother – as he threatened to kill her if she did. I could feel her fear as she described the terror of living with this man. By speaking to me, Deirdre knew she was putting her life on the line. She also knew that by not saying anything, death was probably inevitable. Her partner’s jealousy had grown more intense over time and now his aggression had spilled over on the children. He had always screamed and spat at them if they made any noise, but recently he had covered her five-year old daughter’s mouth and held her so hard that she had almost suffocated. This finally pushed Deirdre to tell someone what was happening.

After listening to her story, and following a long conversation with Deirdre and her mother, she agreed to go directly to her local Garda station and make a full statement on the physical and emotional abuse she had experienced.

Deirdre’s experience may seem extreme and atypical for the majority of her peers. But as caring adults in their lives, it alerts us to some fundamental truths shared by all young people in search of mental health.

The Experiences of Young Adults and Mental Health

Our experience in Jigsaw has shown that young people struggle with what they want to say and with what they cannot say. When they find themselves in distress or in crisis, they may hide behind an outward appearance that suggests an indifferent or problem-free approach to life. Sometimes what young people need to say is not permitted to be spoken about, within their family, school or community. What they need to say may be deemed unsayable, but it doesn’t go away. When the gap between their lived reality and their public persona becomes too great, a young person can feel incredibly isolated and trapped. The stress of trying to maintain a false sense of self can become unbearable. Without words, or some way to express what they feel, young peoples’ distress becomes enacted in symptoms and risky behaviours. Even with someone to talk to, young people may find it hard to open up for the fear of judgement or the fear of having their deepest suspicion about themselves – that there is something fundamentally ‘messed up’ about them – confirmed.

Generally, as adults, and more specifically, as the people who support them who care, it helps to remember that whatever a young person is feeling, there is always a reason for why they are feeling that way. Symptoms of distress, such as panic, anxiety or sadness, don’t appear out of nowhere. They arise from a person’s history, from key relationships in their lives – oftentimes abusive relationships – and from social circumstances where they feel impotent and trapped. Our challenge as listeners is to help young people make sense of their experience so that they can stop feeling they are ‘weird’ and become empowered to face real issues in their lives. This is not easy, especially for a young person who has experienced neglect or violence from the very adults they relied on to feel safe in the world. Their guard may be up and they may test any potential confidant in subtle ways to see if they are trustworthy. When as listeners we fail to grasp the layers of memory and history behind their unsociable behaviour, when we blame them for their problems, or reduce the complexity of their lives to a simple ‘diagnosis’ that explains everything in terms of something ‘wrong’ inside them – rather than something wrong ‘between’ them and their world – we prove to them once again that adults will let them down.

On the other hand, when we can remain steady in the face of their uneasiness, tolerate awkward silences and testing behaviours, we may offer young people something new in their lives: the experience of being heard and of gradually learning to trust. To be that listener requires a capacity to see through the ‘noise’ of their defensive behaviours, recognise the strength and determination they’ve shown to make it this far, and convey to them our belief in their potential to deal with whatever is happening.

The Vulnerability of Young Adults

Returning to the account that opened this article, Deirdre was ready to talk and she did. Her ‘panic attacks’ became understandable when the full picture of what she was dealing with emerged. Her symptoms were her mind’s attempt to manage and to communicate, in the only way it could, what was a terrifying and overwhelming ordeal. In the weeks and months that followed that first meeting, we engaged a range of supports that Deirdre and her children needed to get their lives back. Once Deirdre let people know what had been happening, she found support in surprising places, and little by little, she regained a sense of safety and control over her life.

Mental health is the number one health concern for young people in Ireland.1 Almost 75 per cent of all serious adult mental health disorders are present to a significant degree by 18 years old.2 This may be related to the intensity and vulnerability of youth which can make it a time in our lives when we are most susceptible to mental health difficulties. It is rarely without periods of fear and self-doubt as a young person questions who they are, and whether they have what it takes to make something of their lives. It is also a time when the emotional consequences of childhood trauma can make its presence felt in distressing ways. The search for identity, belonging and purpose are critical psychological challenges in the lifespan between the ages of 12 and 25 years.

Protective experiences for young people include being affirmed in one’s particular gifts and strengths, acceptance by peers, and having a goal that gives direction and focus to their lives. Above all, the presence in the life of a young person of at least ‘One Good Adult’ who knows them personally, believes in them and who is available to them is the strongest protective factor when it comes to his or her mental health.3

Many would argue that life was easier for young people in the past. Embedded in close knit communities, they knew where they stood and what was expected of them. Life’s trajectory came with a map that had milestones and timelines. When they encountered inevitable challenges and setbacks, young people had resources to draw on for guidance and direction. Today, even in small communities where young people may have a sense of place, their identities and sense of belonging can become blurred across their on-line and off-line lives. Add to this the anxiety that many young people feel in the cut and thrust of social media where the possibility of being ridiculed or rejected is a constant risk.

Financially dependent on their parents, young people are tied to living at home beyond a time when such an arrangement is appropriate. Seeing property prices move out of reach, they wonder if they will ever be able to secure a place of their own. In a world addicted to happy endings, many young people are quietly feeling despair as though their lives are over before they’ve even begun.4 Traditionally, a young adult could expect to have left home by twenty-seven, be financially independent, married and have somewhere to live.

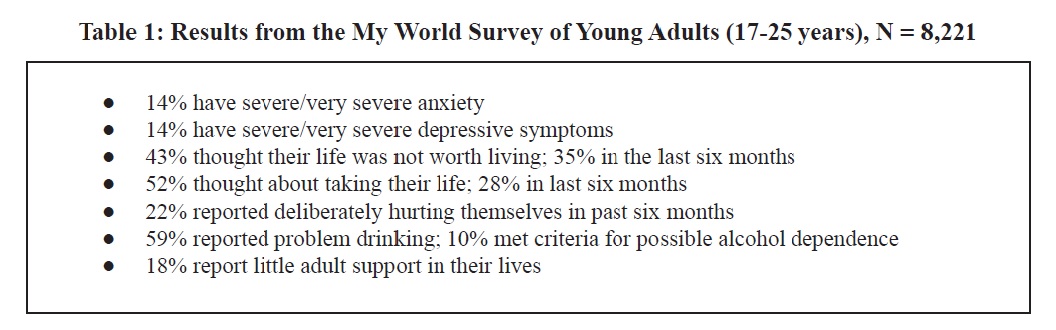

It is not surprising, therefore, that the consequence of this sense of detachment means that many young people report rising levels of anxiety.5 Epidemiological studies6 and extensive needs analyses7 document evidence of the extent of mental ill-health among young people. The most compelling recent evidence regarding the mental health needs of young people in Ireland came from the My World Survey. Table 1 summarises some findings in respect to the 17-25 year old sample.8

The absence of safe accessible support can lead to a mental health crisis becoming compounded by dropping out of education, social withdrawal, reckless behaviour and a growing sense of helplessness and despair. Clearly these factors play a part in the tragedy of suicide.9

Young People’s Experience of Mental Health Services

Research carried out by Jigsaw found significant gaps in mental health services in Ireland.10 One participant in this research commented that:

The biggest problem for young people is mental health and yet there seems to be a huge gap in the system, where the most important thing for young people has been neglected. (Female, aged 21)

Despite the evidence that adolescence is the most vulnerable time when it comes to mental health, Ireland’s mental health system is weakest where it needs to be strongest. Young people and their families in need of emotional support reported that they need ‘somewhere to turn to, someone to talk to’ but that their options to do so are few and far between.11 Where services are available, the challenge for young adults and their families is how to access them. The system is fraught with complex referral pathways, long waiting lists, fees, and very few after-hour options. To illustrate, a parent of a troubled young person commented:

You can’t cross the sectors. It’s all islands. It’s an island here and it’s an island there and some islands are better than others, you know.12

Consultations with young people in both the United Kingdom and Ireland have shown that the needs that young people articulate have more to do with an investment of thought and consideration rather than major capital investment. Young people want to be treated with respect, to be listened to, and not to be dismissed as ‘going through a phase’ or treated like a child. As service providers, our experiences show that the guarantee of young peoples’ confidentiality and anonymity is very important. They want a safe place where they can feel comfortable; this includes somewhere where they can clear their head without being labelled or stigmatised, somewhere where they will not be told to go elsewhere.

Jigsaw: A Step in the Right Direction

The American poet Mary Oliver, in her poem The Journey, has the line ‘One day you finally knew what you had to do’.13 The year 2006 was such a time for me. For the previous twenty-five years, I had heard over and over again the phrase if only from adults in a psychiatric hospital: If only I’d been able to talk to someone and get the support I needed when I was younger, when all this started. Problems and issues that first emerged in the teens of these adults had become entrenched. In the absence of support, they did the best they could to ‘manage’ their troubled inner lives. Substance misuse, self-harm, social withdrawal or simply running with the wrong crowd, turned some crisis in their lives into a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, or a criminal record.

With the help of several others who also felt the need for a new approach to mental health among young adults, Headstrong – the National Centre for Youth Mental Health (now called Jigsaw) was established in 2006. The goal of Jigsaw was to change how Ireland thinks about youth mental health and to support vulnerable young people. Jigsaw puts young people at the heart of the planning process, and invites agencies and professionals in the community to move beyond silo thinking and work collaboratively in a new way. Participation of young people keeps these conversations grounded and practical.

Direct support for vulnerable young people is provided through main-street youth-friendly Jigsaw Hubs, where support from a multidisciplinary team is available, and clear pathways to specialist services are facilitated, if required. Jigsaw also supports young people indirectly though building competence and the confidence of key people in their lives who engage with them every day in schools, colleges, community and youth services.

Jigsaw is now operating in thirteen communities across Ireland. It is a step in the right direction. But there is still a long way to go if we want to strategically improve the mental health of young people in this country, particularly of those who are marginalised and seldom heard.

Conclusion

Young people are seeking to establish a personal identity that ‘does not let them down in their struggle, the struggle for identity, the struggle to feel real, the struggle not to fit into an adult-assigned role, but to go through whatever has to be gone through’.14 They want to be themselves, to speak in their own voice, rather than fit into a role that has been assigned to them. Mental health is central to this struggle. Good mental health means learning to hold and accept tensions and contradictions in their personalities. It is not about being perfect; it is about being whole. For every human being, this involves learning to integrate and reconcile in themselves both light and dark, strength and weakness, success and failure, so that, when a person uses the word I, there is really someone present to support this pronoun.

None of this can happen without a facilitating environment and without people who can calm and steady them in times of crisis, so that they don’t succumb to their fears. These ‘good adults’–parents, siblings, grandparents, counsellors, teachers, sports coaches – show young people the handrails they need to survive tough times and remind them they have what it takes to achieve goals that are important to them.

Mental health is the courageous struggle to step into and own one’s truth. To hide behind some socially desirable version of themselves, to play it safe, leaves a young person feeling empty. But to come out of hiding and risk sharing what feels broken with another takes guts. Sometimes it takes a crisis and the painful realisation that their lives are not working for them to decide to push through their fears and start being real.

That’s what Deirdre did.

Notes

1. The transition to adulthood can include potentially serious mental disorders (See: McGorry, P. (2011) ‘Transition to Adulthood: The critical period for pre-emptive, disease-modifying care for schizophrenia and related disorders’, Schizophrenia bulletin, Vol. 37 (3), pp. 524-530). In Ireland, while the majority of young people function well, mental health difficulties can emerge in early adolescence and peak in late teens and early 20s. For an insight into the experiences and concerns of young adults, see: Dooley, B., and Fitzgerald, A. (2012) My World Survey: National Study of Youth Mental Health in Ireland, Dublin: Headstrong and the UCD School of Psychology. (Available at: http://www.drugs.ie/resourcesfiles/research/2012/My_World_Survey_2012_Online.pdf)

2. Evidence of this is cited in a number of studies including: Hickie, I.B., Groom, G., & Davenport, T. (2004) Investing in Australia’s future: the personal, social and economic benefits of good mental health. Canberra: Mental Health Council of Australia; Kessler, R.C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., et al. (2015) ‘Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distribution of DSM-IV Disorder in the National Co-morbidity Survey Replication’, Archives General Psychiatry, Vol. 62, pp. 593-602; Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T.E., et al. (2003) ‘Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective- longitudinal cohort’, Archives General Psychiatry, Vol. 60(7), pp. 709-17.

3. Dooley B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2012) My World Survey: National Study of Youth Mental Health in Ireland. Dublin: Headstrong and UCD School of Psychology.

4. There is now a growing body of evidence showing the negative impacts of social media on mental health. For example, see Pantic, I. ‘Online Social Networking and Mental Health’, (2014) Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, Vol. 17(10), pp. 652-657.

5. Cannon, M., Coughlan, H., Clarke, M., Harley, M., & Kelleher, I. (2013) The Mental Health of Young People in Ireland: a report of the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research across the Lifespan. (PERL) Group. Dublin: Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

6. These studies include: Martin, M., Carr, A., Burke, L., Carroll, L., Byrne, S. (2006) The Clonmel Project: Mental Health Service Needs of Children and Adolescents in the South East of Ireland. Dublin: Health Service Executive; National Office for Suicide Prevention. (2009) Annual Report 2009. Dublin: Health Service Executive. (Available at: http://www.nosp.ie/ annual_report_09.pdf)

7. Illback et al. (2010) and Illback and Bates (2011) report that young adults in Ireland exhibit high levels of psychological distress that is often amplified by poor access to support services. See: Illback, R.J., Bates, T., & Hodges, C., (2010) ‘Jigsaw: engaging communities in the development and implementation of youth mental health services and supports in the Republic of Ireland’. Journal of Mental Health, Vol. 19, pp. 422-35; Illback, R.J., & Bates, T., (2011) ‘Transforming youth mental health services and supports in Ireland’. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, Vol. 5, pp. 22-27

8. Dooley, B., & Fitzgerald, A. (2012) ‘Methodology on the My World Survey (MWS): a unique window into the world of adolescents in Ireland’. Early Intervention Psychiatry, Vol. 7(1), pp.12-22

9. See: http://www.nsrf.ie/statistics/suicide/

10. Bates T., Illback R., Scanlan F., & Carroll L. (2009)Somewhere To Turn To, Someone To Talk To. Dublin: Headstrong National Centre for Youth Mental Health.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Oliver M., The Journey in Dream Work. Atlantic Press Publishers, 1986.

14. Winnicott, D.W., Caldwell, L., and Taylor Robinson, H., The Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott, Volume 6. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, pg. 429.

Dr. Tony Bates is a clinical psychologist and founder of Jigsaw – The National Centre for Youth Mental Health, Ireland.

Dr. Bates would like to pay particular thanks to Deirdre (not her real name) for permission to reference her story.