Introduction

Current government prison policy envisages the closure of the Dóchas Centre in Mountjoy and the opening of new women’s prisons at Thornton Hall, in north Dublin and at Kilworth, Co. Cork, resulting in a doubling of the number of places for women prisoners. This radical expansion of prison capacity for female offenders is being justified by the authorities on the grounds that the existing facilities at Dóchas and in Limerick Prison are routinely overcrowded and that the prison building programme being undertaken at present needs to be ‘future proofed’ to cater for an on-going increase in the female prison population.

It will be argued in this article that the current policy direction ought to be reconsidered. This argument is rooted in the fact that there is no evidence of any trend in convictions against women suggesting that a radically increased number of prison places is needed. Furthermore, it is apparent that a significant proportion of women committed to prison are on remand or are detained under immigration legislation and that the majority of those committed under sentence have been convicted of crimes that are at the lower end of the scale of seriousness. For all these groups, non-custodial options could be far more widely used if policy and resources were so directed.

This article is intended to be an overview of the situation which obtained during the period 2003 to 2006; it is not claimed to be a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between women, crime and imprisonment in that period. However, even this limited exercise highlights the breadth of research that could and should be carried out in this area before substantial public resources are spent on building and operating a greatly increased number of prison places for female offenders.

Convictions against Women

Data Source

The analysis of convictions against women presented in this article is based on data contained in the Central Statistics Office (CSO) report, Garda Recorded Crime Statistics: 2003–2006.1 The CSO issued this report in April 2008, having taken over the compiling of crime data from An Garda Síochána in 2006. The report acknowledges the cooperation between the CSO, the Courts Service and the Gardaí which made possible the creation of such a comprehensive database.

An important feature of the report is that it employs the new Irish Crime Classification System (ICCS), which has changed the way in which crimes are recorded. The CSO acknowledges that the report contains ‘little by way of trend analysis’, but says that the publication ‘is very much seen as introducing the ICCS and setting the baseline for future work’, and that henceforth there will be ‘an annual cycle of reports’ which will include trend information.2

The report also draws attention to the fact that the statistics presented relate only to crime incidents brought to the attention of, and recorded by, An Garda Síochána: such incidents, it points out, represent ‘only one part of criminal behaviour in Ireland’.3

The CSO report includes statistics in relation to all crime incidents recorded over the period 2003–2006, as well as statistics in relation to detections, proceedings and outcomes of proceedings in respect of these incidents.

A core feature of the way the statistics in the CSO report are presented is that data on detections, proceedings and outcomes of proceedings are attributed to the year in which the incident to which they relate was recorded. Thus, the handing down of a conviction for an offence by the courts might occur in 2006 but if the offence had taken place in 2004, then the latter is the year under which the conviction would be recorded. This process means that the conviction figures given in the CSO report for any of the four years, 2003–2006, may yet increase, as further detections, proceedings and convictions take place. This is obviously most likely to happen in respect of the figures for 2006.

In regard specifically to convictions, the CSO report provides a detailed breakdown by crime category, and by sex and age-group. It is the material in this section of the report which made possible the analysis that is presented in this article.4

In the context of the issues discussed here, one notable gap in the CSO report is the lack of a breakdown by sex of the statistics on court proceedings taken. Thus, while the statistics published make it possible to chart the trend in convictions against women over the four years, 2003 to 2006, the absence of a breakdown by sex of the figures for proceedings means it is not possible to show the trend in convictions as a percentage of all proceedings taken against women.

Convictions: Key Findings

Trends in Convictions

Over the period examined (2003 to 2006), the annual average number of women convicted of an offence was 9,168. It should be borne in mind that the figure for the number of women convicted of an offence in a given year does not equate with the number of convictions against women in that year: the latter figure is likely to be higher, since some women will have been convicted of more than one offence.

The trend over the four-year period was U-shaped: the number of women convicted for an offence recorded in 2003 was 9,463; the number fell to 8,771 in 2004, before increasing slightly in 2005 and almost returning to the 2003 level in 2006, when 9,329 women were convicted.

An important contextual feature of the trend in convictions is the fact that during this four-year period the overall population of the country grew rapidly, which means that the rate of convictions per 1,000 of the female population actually declined. Between the census years, 2002 and 2006, the female population rose by nearly 150,000 (an increase of 7.5 per cent). Based on the 2002 population figure, the 2003 rate of convictions for women (per 1,000 of the female population) was 4.8; the rate for 2006 was 4.4.

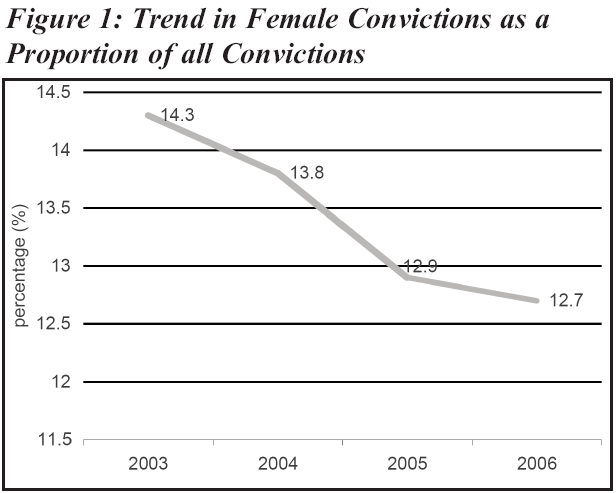

Over the four-year period, women represented a declining proportion of all persons against whom a conviction was given – this reduction reflects the increase of more than 7,000 in the number of men against whom there was a conviction (see Figure 1).

Ages of those Convicted

Of females convicted for an offence recorded in 2003, girls under 18 represented 3.8 per cent of the total. Over the ensuing three years, however, this figure fell and by 2006 stood at 2.3 per cent.

The statistics for women convicted for an offence recorded in 2006 show that there were as many as 629 (6.7 per cent of the total) for whom an age was ‘unavailable’. The majority of these women were convicted for ‘Road Traffic Offences’. The 2006 figure for ‘age unavailable’ is substantially greater than that for the previous three years when the average number was 21 (0.2 per cent of the total). No information is provided in the CSO report to indicate the reasons for the anomalous 2006 figure.

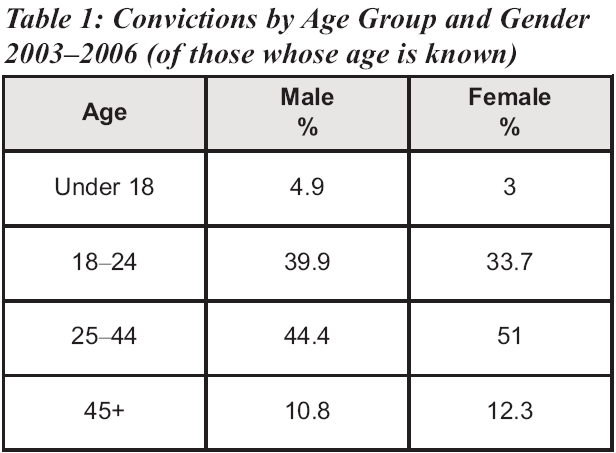

Table 1 gives the breakdown by age group of both males and females convicted of a crime recorded in the period 2003 to 2006: in light of the size of the ‘age unavailable’ group in 2006, it was decided to base the calculation of numbers in each age group on the population for whom an age was recorded.

Compared to men, a lower proportion of women convicted of an offence recorded over the period were under 25 years of age (36.7 per cent as against 44.8 per cent). More than 70 per cent of women convicted were over 25, with 51 per cent in the age group 25–44 and 12.3 per cent over 45.

Categories of Offence

In the CSO report, offences are recorded under sixteen different headings. Four of these categories account for the vast majority of offences recorded between 2003 and 2006 for which women were subsequently convicted:

- Group 14: Road Traffic Offences

- Group 8: Theft and Related Offences

- Group 13: Public Order Offences

- Group 4: Dangerous or Negligent Acts

‘Road Traffic Offences’: These constituted the largest category of offence for which women were convicted.

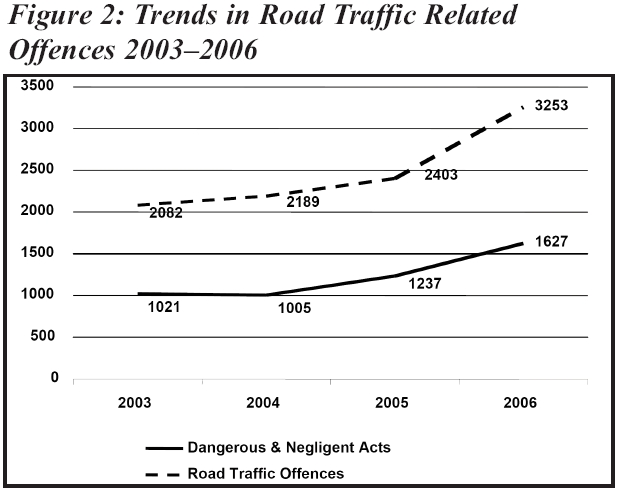

The number of women convicted for such offences, added to the number convicted for ‘Dangerous or Negligent Acts’, represented around 50 per cent of the total number convicted for an offence recorded in each of the four years examined.

The majority of convictions in relation to ‘Dangerous or Negligent Acts’ were in respect of road traffic incidents, but these were for more serious offences than those categorised as ‘Road Traffic Offences’. As Figure 2 reveals, convictions for both categories of offence showed a clear upward trend. It is very likely that, at least to some extent, this rise in convictions was the outcome of a marked increase in Garda operations on the nation’s road.

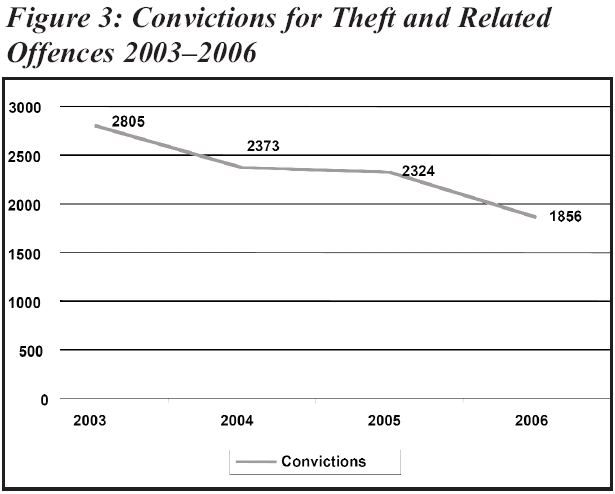

‘Theft and Related Offences’: This was the second largest category of offence for which women were convicted. It showed a downward trend, with nearly 1,000 (33 per cent) fewer convictions in 2006 than in 2003 (see Figure 3).

A drop of this scale is obviously noteworthy and may be due to a number of factors, including a real reduction in theft by women, a reduction in reporting to the Gardaí of incidents of theft, or a reduction in the prosecution of alleged offences. However, it may also be the case that further convictions for theft and related offences may yet arise (particularly in regard to the final year examined, 2006) as proceedings in respect of incidents recorded are concluded.

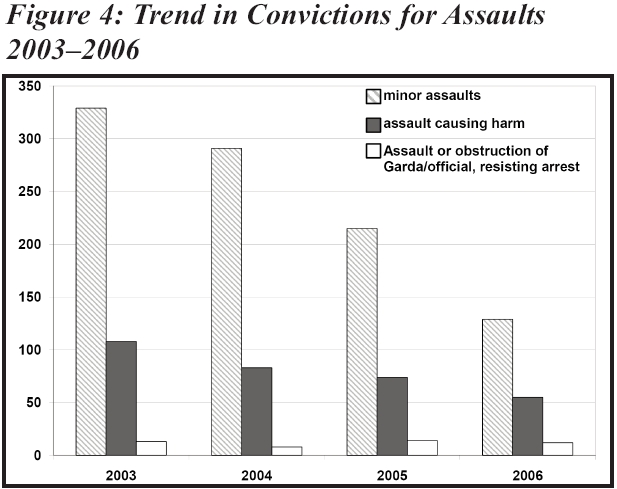

Assaults: As Figure 4 shows, there was a marked reduction between 2003 and 2006 in the number of women convicted of assault, with this dropping from 450 to 207. Again, however, it may be that these figures will increase as proceedings in relation to incidents recorded (especially those for 2006) reach a conclusion.

Overall, it is noteworthy that the number of women convicted of assault over the period represented a relatively small percentage of the total number convicted of an offence – 1,331 out of 36,671 (3.6 per cent).

The great majority of women – 72.5 per cent – convicted of assault during the four-year period were found guilty of a ‘minor assault’; 24 per cent were convicted for the offence, ‘assault causing harm’, and 3.5 per cent for ‘assault or obstruction of Garda/official, resisting arrest’.

Imprisonment of Women

Data Source

The statistics on the imprisonment of women over the period 2003 to 2006 come from the Annual Reports of the Irish Prison Service.5 These statistics offer two means of obtaining a picture of women in prison – one, by providing information about the women who come into the prison system during a given year and, two, by providing information about the female prisoner population on a specific day in December of that year.

There are, however, gaps in the data presented in the prison reports from one year to the next: these inconsistencies present significant obstacles in analysing trends over time.

It should be noted that the statistics on committals under sentence do not include information as to the year in which the offence giving rise to the conviction was recorded. On the basis of the information currently available, therefore, it is not possible to express committals under sentence in a particular year (i.e., the data provided in the Prison Service reports) as a percentage of convictions for that year (i.e., the data provided in the CSO Crime Statistics report).

Number of Committals

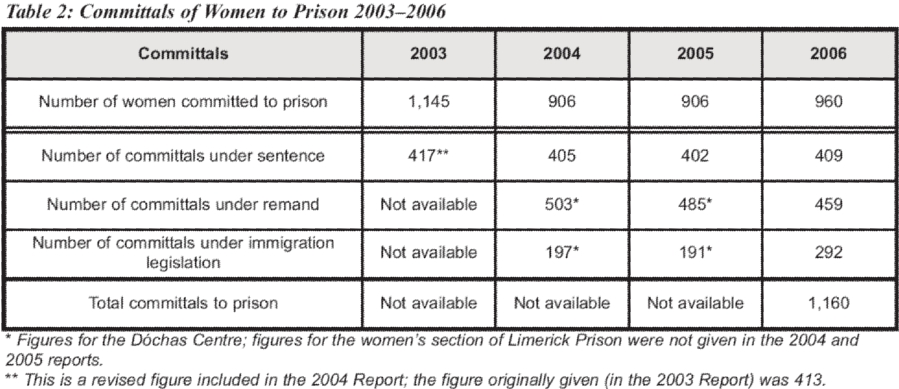

One of the most striking facts revealed by the Prison Service statistics is the number of women committed to prison in any one year.

Whereas the daily average number of female prisoners in each of the four years 2003 to 2006 was around 100 (the highest daily average being 106, in 2006, and the lowest 97, in 2003) a total of over 1,100 women were committed to prison in 2003, and in each of the subsequent three years over 900 women were sent to prison (Table 2). The wide gap between the numbers committed and the daily average is, of course, due to the very short periods many women spend in prison.

It should be noted that the number of women committed to prison in any one year does not equate with the total number of committals in that year – the latter is likely to be higher since some women may be committed more than once during the same year either for different crimes, or because they are first committed on remand and then under sentence. Only the 2006 Annual Prison Report provides sufficient data to indicate how significant this difference might be: it shows that while a total of 960 women were sent to prison in that year, there were, in all, 1,160 committals.

Non-Sentence Committals

Leaving aside imprisonment under sentence, women may enter prison having been committed under immigration legislation or on remand while awaiting trial or sentencing by the court. Unfortunately, the Prison Service Annual Reports provide little detailed information on either immigration related committals or remand committals.

Immigration: Only in the 2006 report is an overall figure given for the number of female committals under immigration legislation. In that year, there were 292 such committals, representing as much as 25 per cent of all female committals (Table 2).

In the reports for 2004 and 2005, a figure for committals under immigration legislation is provided for the Dóchas Centre, but not for the women’s prison in Limerick. In the 2003 report, no breakdown by sex of the committals under immigration legislation is provided (Table 2).

While the annual reports give overall statistics on the length of time spent in prison by those detained under immigration legislation, no breakdown by sex is provided. The statistics for immigration detainees as a whole show that the great majority remain in prison for less than seven days. A significant minority, however, spend thirty days or more in prison – in 2006, for example, the figure was 10 per cent of those detained under immigration legislation.

Remand: Again, as Table 2 shows, the 2006 report alone gives a figure for the total number of committals on remand; figures for 2004 and 2005 are provided only for the Dóchas Centre, and in the 2003 report no figure at all for remand committals is provided. It is evident from the information available in the 2004 to 2006 reports that the number of committals under remand exceeds those under sentence.

In the Prison Service Annual Reports for all but one of the four years examined, the profile of prisoners on a specific day in December of that year omits any information in relation to women on remand. The exception is 2003, the report for which reveals that 24 per cent of all female prisoners on 2 December 2003 were on remand. By contrast, on the same day, just 15 per cent of male prisoners were on remand.

Committals under Sentence

As Table 2 shows, the total number of committals under sentence remained more or less static over the four years. Furthermore, there were no significant changes in the types of offences for which women were committed over the period.

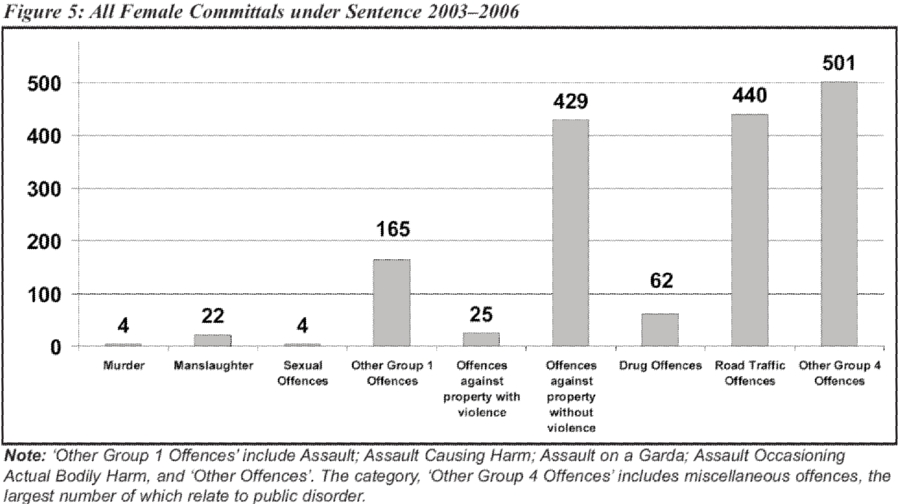

Figure 5 (below) gives the total committals under sentence 2003–2006, broken down into the offence categories used in the Prison Service Annual Reports. It reveals that only a minority of the prison sentences imposed were for the most serious crimes. The statistics used to create Figure 5 show that there was a fall in committals for violent offences over the period.

The single largest category was, ‘Other Group 4 Offences’, which can include offences varying in seriousness from ‘Debtor Offences’ to ‘Possession of Knives and Other Articles’. However, it was ‘public order offences’ which constituted the largest sub-group of offences in this category.

The second largest category was ‘Road Traffic Offences’ (440 over four years), and the third largest was ‘Offences against Property without Violence’ (429).

Profile of Prison Population

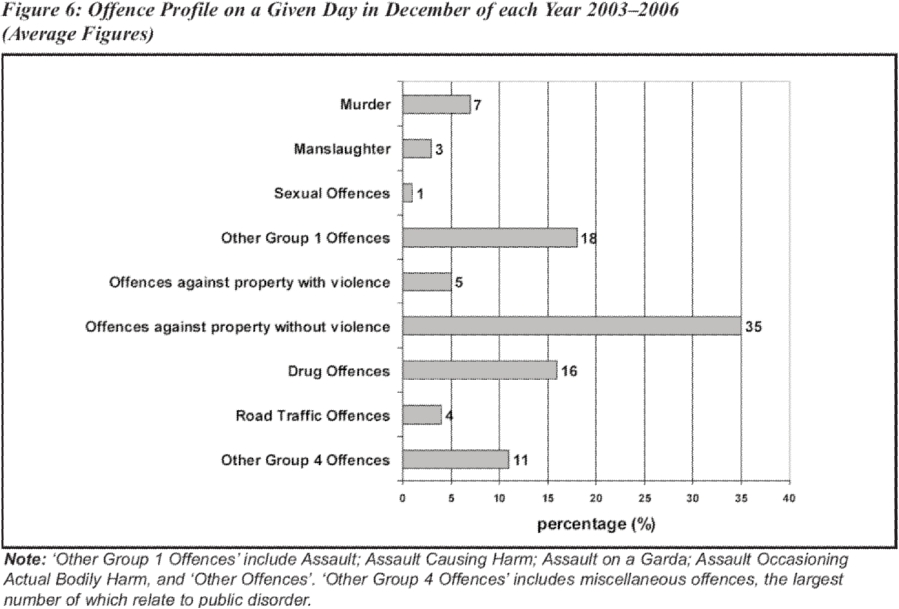

The statistics on female committals in each year need to be read alongside the statistics which provide a ‘profile’ of the female prison population on a given day in December each year. Included in these statistics are the offences for which the women in prison on that day had been committed. Figure 6 below shows the percentage of sentences falling into the different offence categories, giving the average for the four years.

Analysis of the data used to compile Figure 6 reveals that of the women in prison in December 2006, just 2 per cent were there because of a conviction for ‘Offences against Property with Violence’ as compared to 10 per cent in December 2003. However, in real terms, this drop was only from 7 to 2 prisoners. The percentage of women who had been sentenced to imprisonment for ‘Offences against Property without Violence’ was higher in 2006 than in 2003 (41 per cent as against 33 per cent) and in this case the change may be of somewhat greater significance, as the numbers rose in absolute terms from 23 to 34.

On average over the four years, 18 per cent of the women in prison had been convicted of ‘Other Offences against the Person’ (mainly assaults). However, this average figure hides a story of decline over the four years: in December 2003, 21 women in prison under sentence (or 31 per cent) were being held for an offence in this category, whereas by December 2006, just 7 women (9 per cent of the total) were in prison for such offences.

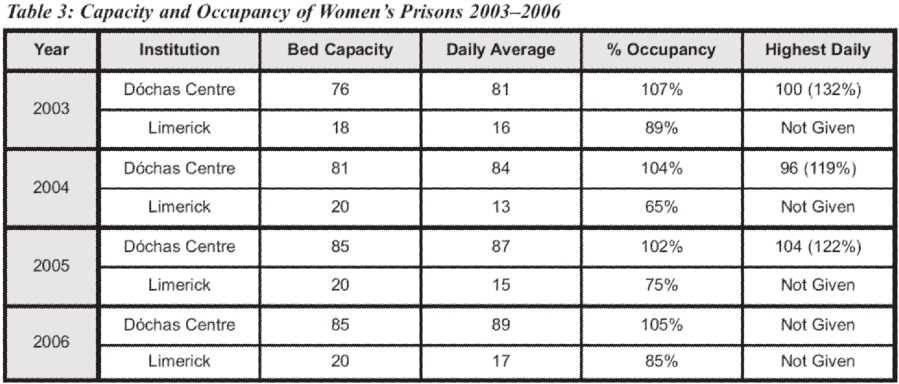

Overcrowding in Female Prisons

A key argument being used to justify the expansion in places for women prisoners is overcrowding in the prisons where women are detained. Table 3 presents data from the Annual Reports on the capacity and occupancy of the two prisons for women – the Dóchas Centre and the unit for female prisoners in Limerick Prison – over the period examined.

It is immediately obvious that in each of the four years covered the Dóchas Centre was overstretched. The figures for Limerick show occupancy to be less than capacity. However, it should be borne in mind that the unit for female prisoners in Limerick operates on the basis of two per cell – with cells providing very limited space, and bunk beds used to accommodate the two people.

There is indeed, therefore, a problem of overcrowding in Irish prisons for women. But is this a problem to which the only, or the most appropriate, response is an increase in the number of places?

The data on the offences for which women are imprisoned (presented in Figures 5 and 6), which highlights how few are under sentence for the most serious crimes, would suggest there is considerable scope for using non-custodial sentences in response to the crimes committed by women. As already noted, ‘Offences against Property without Violence’ constituted one of the largest categories of offence for which women were committed to prison under sentence. Offences in this category, it could be argued, do not warrant a custodial sentence. Indeed, the same could be said in regard to many of the 501 committals under the largest category, ‘Other Group 4 Offences’, the greatest number of which, as already noted, are public order offences.

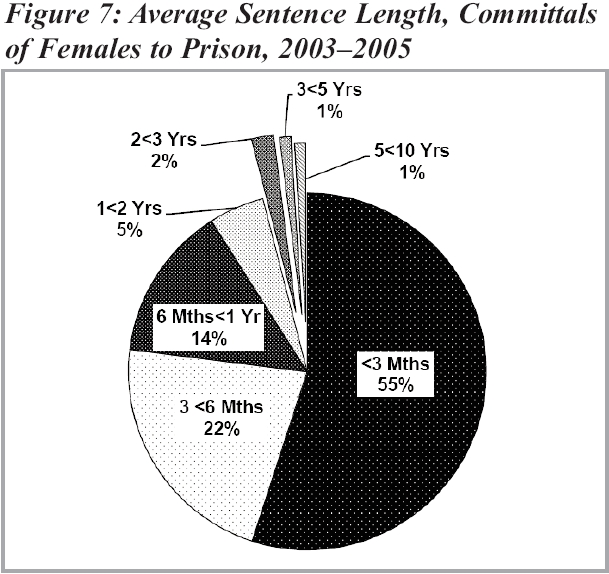

The data in Figure 7 reinforces this argument. This gives a breakdown of the average length of sentences in the case of female committals under sentence. Unfortunately, it was not possible to present information for the full four years between 2003 and 2006, since the Annual Report for 2006 does not give a breakdown that would show the length of the sentences imposed on women committed on conviction in that year.

Figure 7 reveals the striking fact that on average over the three years, 2003 to 2005, 77 per cent of all committals of women under sentence were for a period of less than six months and only 4 per cent were for more than two years.

Conclusion

The data sources used in this article provide two distinct ways of looking at the issue of women and crime. Although it is not possible to directly link information from the two sources, the picture emerging from each set of statistics is broadly similar.

The analysis shows that over the four years, 2003 to 2006, and in a context where the population of the country was rising, there was no evidence of any marked upward trend in convictions by the courts against women. Neither was there an increase in convictions for serious crimes.

Regarding the imprisonment of women, one of the most striking facts emerging from the analysis is the scale of committals under immigration legislation and under remand. Although there is a lack of detail in relation to such committals it is clear that, taken together, these greatly outnumber committals under sentence.

Many groups, including the Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland, have advocated that detention should not be used in relation to asylum and migration issues. They have argued that non-custodial alternatives should be used instead, and that if detention is unavoidable then centres other than prisons should be used.

Likewise, given the non-violent nature of the vast majority of crimes committed by women, the extent to which imprisonment is used for women on remand deserves serious scrutiny. One alternative that could form part of a process of lessening the use of imprisonment for remand purposes would be the development of a network of bail hostels for women.

Data in relation to the crimes for which women are given a sentence of imprisonment, and the duration of these sentences (Figure 6 and Figure 7), strongly suggests that imprisonment is being used in the case of crimes that are far from being at the serious end of the scale.

However, it has to be acknowledged that basic data on convictions and imprisonment cannot reveal the extent to which factors other than the actual crime for which a woman appears in court may serve to influence the decision to impose a sentence of imprisonment. Are women being imprisoned because they have had several convictions and judges run out of patience or decide that the possibilities offered by non-custodial sentences have been exhausted? Might it be that judges see a custodial sentence as the only way that some women will have access to services they desperately need but which are unavailable in the community? If this is the case, it must be said that imprisonment is a very inappropriate – and expensive – way of providing needed social supports. Clearly, these are the type of questions that need to be explored in future research into the Irish criminal justice system.

While we await the undertaking of such research, however, we need to keep in mind the findings of the research that has been already carried out into the background of women in prison in Ireland. These findings highlight the poverty, family breakdown, housing insecurity, educational disadvantage and mental ill health that characterise the lives of many women who come into prison.6 They show, in other words, the personal and social circumstances which lie behind the offences committed by the women who end up being imprisoned – circumstances which prison in itself can do little to address.

A particularly interesting question concerning the use of imprisonment is whether the existence of a set number of prison places gives rise to a systemic tendency to fill those places. If there is an imperative within the criminal justice system to somehow ensure that available prison places are filled, what are the implications of an increase in places on the scale currently being planned by the Irish prison authorities? Not least of all, what are the financial implications, given that the average cost of detaining a person in prison in Ireland now comes to around €100,000 per annum – and given also the problems now facing the public finances?

The analysis presented in this article suggests there is a strong case for questioning the use of imprisonment for the offences for which most women are sent to jail; for questioning the imposing of short prison sentences, during which little by way of rehabilitative work can be undertaken, rather than alternative penalties; and for questioning why we as a society cannot devise more effective and appropriate responses to the situation of the many vulnerable women who come into the criminal justice system. There is certainly a very strong case for querying any proposal to double the number of places provided for the imprisonment of women in Ireland.

Notes

1. Central Statistics Office, Garda Recorded Crime Statistics: 2003–2006, Dublin: Stationery Office, 2008.

2. Ibid., p. 15.

3. Ibid., p. 15.

4. Ibid., Table 2.1a–Table 2.1d.

5. Irish Prison Service, Annual Report 2003; Annual Report 2004; Annual Report 2005, Dublin: Irish Prison Service; Annual Report 2006, Longford: Irish Prison Service.

6. Christina Quinlan, ‘The Women We Imprison’, Irish Criminal Law Journal, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2003; Celesta McCann James, ‘Recycled Women: Oppression and the Social World of Women Prisoners in the Irish Republic’, Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Ireland, Galway, September 2001; Barbara Mason, ‘Imprisoned Freedom: A Sociological Study of a 21st Century Prison for Women in Ireland’, Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science, 2004; C.M. Comiskey, K. O’Sullivan and J. Cronly, Hazardous Journeys to Better Places: Positive Outcomes and Negative Risks Associated with the Care Pathway Before, During and After Admittance to the Dochás Centre, Mountjoy Prison, Dublin, Ireland, Dublin, 2006 (report for the Health Service Executive).

Daragh McGreal was an Intern with the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice during summer 2008

Tony O’Riordan SJ is Director of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice

The authors wish to thank Prof. Ian O’Donnell, Margaret Burns and Eoin Carroll for their helpful comments on a draft of this article