Introduction

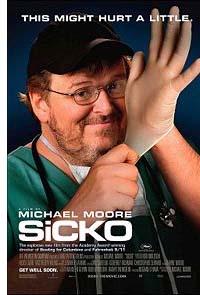

Michael Moore’s film, Sicko, now on general release, dramatically highlights how the wealthiest country in the world, and one which spends a much larger percentage of its GDP on health than other developed countries, fails to provide an adequate and fair system of care for its citizens. The film carries its message through people’s own accounts of being denied medical care or being required to pay exorbitant amounts of money for services; it does so also through the voices of people who have worked in America’s health insurance industry and who reveal how, for that industry, the imperative of making profit takes precedence over enabling people to obtain care.

Sicko makes a person want to weep at the unnecessary human suffering that results from this system. But alongside the heart-rending stories, Moore employs humour to highlight the absurdity as well as the cruelty of the system. Sometimes the humour is unintended – as when it emerges that a letter we are shown, in which a woman’s requests for referral for specialist services are turned down, is from ‘The Good Samaritan Medical Practice Association’. Perhaps the Good Samaritan should sue?

There are undoubtedly many Good Samaritans working in US health care. But Sicko shows over and over how they work in a system that is structurally unjust and a shameful example of a country failing its own people.

US Census Bureau data show that, in 2006, 47 million Americans were without health insurance, 1 million more than in the previous year, and 8.6 million more than in 2000. Early on in Sicko, Moore draws attention to the fact that as many as 18,000 people a year die because of lack of medical insurance. The opening sequences of the film show two examples of the choices which may face people who do not have insurance. Both concern situations that are not life-threatening: yet how can it be right that a wealthy country would force one of its citizens to choose which of the two fingers he had lost in an accident should be re-attached – since the price of having both treated was more than he, and indeed most people, could afford?

Insurance that Isn’t

For the most part Moore’s film is not, in fact, about those who are without insurance but rather about those who could qualify for insurance coverage (through, for example, employer schemes) but who don’t because of pre-existing health conditions and those who do qualify but find that the restrictions that are part of their insurance result in their being denied cover for needed care. And so we see a sequence where one insurance company’s list of excluded conditions unfolds and unfolds until one wonders, ‘what is left that is covered?’ And we see a woman who had undergone surgery being denied payment because she had failed to reveal a minor, unrelated, medical condition in her original application for insurance. We see a middle-aged, and middle class, husband and wife, who had both experienced serious illness, and who had been made bankrupt as a result of medical expenses not covered by the insurance they held. Having lost their home, they now had to move State to live in the spare room of their daughter’s house. Their distress and bewilderment at what was happening to them is heart-rending. And even worse still are the stories of how the failure of insurance to provide cover for critically important care had resulted in death.

Profit before People

The film shows a health system in which some doctors are paid, not to use their skills to care directly for patients, or to undertake research that might advance medical knowledge, or promote public health, but rather, as employees of private, profit-making insurance companies, to exercise their ingenuity to come up with reasons why patients should be denied treatment. A doctor and former employee of an insurance company tells Moore: ‘In all my work, I had one primary duty – to use my medical expertise for the financial benefit of the organisation for which I worked.’ The insurance companies argue that their decisions do not deny people treatment – they only deny people payment for treatment.

Michael Moore is unhesitating in allocating blame for the unfairness and cruelty of a system that leaves so many with their health needs unmet and/or with unpayable debts. At the heart of the issue is the for-profit nature of much of American health care, which turns what should be a service to meet fundamental human needs into a business where the ultimate criterion of success is not lives saved, or pain eased, or health recovered, but simply profit. In effect, Sicko shows us what happens when a country ends up having a health industry rather than a health service.

Do other Countries do Better?

In the second half of the film, Moore visits Canada, France and the UK to highlight that health care systems that provide access to all, regardless of income, are possible, and that such systems are not characterised by the horrors which opponents of fundamental reform of the US system allege are inevitable in any form of ‘socialised’ health care. The film will be faulted for presenting an overly positive picture of health care in these countries, failing, for example, to examine the difficulties caused by delays in accessing services, or concerns about rising costs.

Yet, for all their problems, such systems reflect the commitment these societies made at certain points in their history to treat all their people as equal when it comes to accessing health care and thus to make health services available on a universal basis. The case for universal provision is well summed up by one man interviewed during the visit to Canada. Asked by Moore, ‘Why do you expect your fellow Canadians who don’t have your problems to pay for a problem you have?’, he replies: ‘Because we would do the same for them.’ And then Moore asks: ‘What if you just had to take care of yourself?’ To which he answers: ‘[There are] lots of people who aren’t in a position to be able to do that.’

However, Moore’s film fails to draw attention to how comprehensive health care systems are increasingly under threat, not so much from rising costs resulting from new treatments and increasingly ageing populations, although these are undoubtedly very significant factors, but from an increasing encroachment of the private, for-profit form of health care that he criticises in the American context.

A Visit to a Near Neighbour

Even more than the rest of the film, its final section has the potential to raise the blood pressure of large numbers of its American viewers. Noting that there is one piece of US territory where people are entitled to top-quality health care free at the point of delivery, Moore, accompanied by some Americans with chronic health problems, makes an attempt to enter that place – namely, the US Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay. Needless to say, they are duly warned off attempting to land. Moore and a larger group of patients then proceed to try to access the health care provided in Cuba, asking that they be given the same, no less or no more, health care as is provided for Cubans.

The resultant scenes where the US visitors have their conditions reviewed and then receive, free of charge, the care they need, are ripe for the criticism of being stage-managed. And yet … there is, for this viewer at least, nothing stage-managed about the sheer relief on the faces of the people concerned as they not only receive treatment but experience being treated as a person in need of care rather than a consumer of ‘product’ that has to be purchased at a prohibitive price.

Moreover, there is no getting away from the fact that they were in Cuba only because their own country had failed to provide the health care they needed. Most of the people who travelled to Cuba with Moore had developed their illnesses as a result of working on Ground Zero after 9/11 – working not as employees of the emergency services but as volunteers. One woman put it thus: ‘I wanted to help; I was trained for this; you see somebody who’s in need, you help them.’ When these volunteers developed serious health problems that were the direct result of their work on Ground Zero, the reward for their efforts was to find the authorities resolute in their position that since these were volunteers and not employees they were not covered by insurance.

As is the case with the treatment of the Canadian, French, and British systems, Moore does not attempt any wider analysis of the Cuban system. A number of critics of the film have pointed out that Moore makes no comment on the fact that a World Health Organization ranking of countries’ health care provision, shown in the film, reveals the US to be in a better position than Cuba. To which one might say that ranking 37th, just two places ahead of Cuba, a country whose GDP is but a fraction of that of the US, is hardly much of an achievement for a country with the level of income and wealth which the US possesses.1

An Alternative Vision

In summer 2007, around the time that Sicko was going on general release in America, the Catholic Health Association of the United States, an umbrella group of more than 1,200 US Catholic health care sponsors and facilities, issued a statement, Our Vision for U.S. Health Care. The statement argued that: ‘The U.S. has the obligation to ensure that no one goes without any of life’s basic necessities, including health care.’2 In outlining its vision for a reformed system, it argued that this should include the following elements:

- be available and accessible to everyone;

- pay special attention to the duty of protecting the poor and vulnerable;

- be health-and prevention-oriented with the goal of creating healthy U.S. communities;

- put patients and families at the center of the care process.3

Sicko vividly illustrates how far current US health care is from realising such ideals. The film is not a measured policy analysis of the system, and of possible alternatives. Michael Moore is a polemicist and he is using a form of mass entertainment to drive home his case. This film is not subtle; it is open to the criticism that it is emotive and does not attempt to give a balanced overall picture of the issues covered. Nonetheless, it remains a powerful indictment of the insurance companies, pharmaceutical corporations, and health providers who operate America’s for-profit health care system, and of the politicians who are the willing recipients of the political and financial support of these industries.

The film concludes with a plea to Americans to devise a health system that would allow people to care for one another in times of difficulty. It asks them to draw on their own image of themselves as ‘a good and generous people … people with a good heart and a good soul’ who look out for one another – as expressed, he suggests, in a long tradition of voluntary action and of willingness to lend a neighbour a hand – to create a more humane and just system of health care.

It Couldn’t Happen Here – Could It?

Sicko is a film clearly made for an American audience; its exposé of the deficiencies of the US health system and its portrayal of health care in a number of countries with universal provision are aimed at convincing Americans that a better system is possible. But what are its lessons for Irish viewers?

The half of the Irish population that now has private health insurance is not subjected to the exclusions and the denial of coverage that the film so tellingly highlights as occurring in the US system. But we should be aware that it may well be that just two words protect us from the barbarity of that system – ‘risk equalisation’, the concept that risks are shared so that those who have chronic conditions, or who are older and more vulnerable to illness, do not have to pay more than the young and healthy for the insurance plan that they choose (or perhaps one should say, ‘can afford’). But ‘risk equalisation’ has already been challenged in the High Court; the decision of that Court in favour of retention is now being appealed in the Supreme Court.4 If in either the near future, or the long term, the challenge to risk equalisation is upheld, Ireland could find itself faced with the sort of exclusions and prohibitively expensive coverage highlighted in Sicko.

Our Limited Sense of Solidarity

The risk equalisation of Irish health insurance can be considered an expression of social solidarity. But we should be in no doubt that it is a qualified kind of solidarity. Private health insurance in Ireland is no longer what it was when the VHI was established by the State in the 1950s – a means whereby people in higher income groups could cover themselves against the cost of illness, in a context where they were not eligible for public hospital care. For several decades now, everyone in the country is entitled to use the public hospital system – not entirely free of charge (except for those on medical cards) but at a nominal cost. But over the past decade increasing numbers of people have been taking out private health insurance, and a major reason they do so is that they fear delays in accessing treatment, and are concerned about the quality of treatment, in the public system. And so presumably the members of our Government, and the opposition members of the Oireachtas, and the senior officials in our health services (including in the HSE which is responsible for the administration of the public health system), and members of the media, and church leaders, and the key people in the social partnership process – in other words, all those who make policy or who are in a good position to influence it – have opted out of reliance on the public system. In present circumstances, people buy private health insurance, sometimes at a very high cost relative to their income, because they feel it is the only prudent option. Still, there remains a question that we cannot avoid: ‘If the public system isn’t good enough for me, then who are the people it’s supposed to be good enough for?’

We may not have a health care system that operates in such a grossly unjust and uncaring manner as that portrayed in the Michael Moore film. But let us not make any mistake: the Irish health care system is structured to be inequitable. Unlike Canada and many western European countries, Ireland never came to a point where it made a commitment to devise a health care system premised on treating people on the basis of need, not ability to pay.

In many ways in recent times we have been making policy choices that are taking us further and further away from that principle. Dating back twenty years, to the cutbacks of 1987, our public system entered more than a decade of under-funding. Increases over the past number of years have been insufficient to create adequate overall capacity in the public system, given the depth and length of the period of retrenchment and given the growth in population, particularly of older people who are most vulnerable to illness.

The 2001 Health Strategy promised significant development of the public health system, including the provision of 3,000 extra hospital beds,5 but that Strategy has in effect been left to grace bookshelves, with no evidence of any commitment to implement it.

Meanwhile, in a whole series of policy decisions the Government has been acting to build up services provided by the private sector for those who can pay. So, for example, we have had the introduction of tax relief for building private, for-profit hospitals, and, notoriously, the imposition of private hospitals on public hospital grounds. It now appears that some of the promised new minor injury clinics, which in the June 2007 Programme for Government were presented as public facilities, will be private.6

Inching towards an American-type System?

The decisions of the past few years have not only further entrenched the two-tier nature of Irish health care, but have handed provision of services paid for by the public system over to the private, for-profit sector. Thus, for example, instead of expanding public hospital capacity we have had the creation of the National Treatment Purchase Fund, which ‘buys’ treatment for public patients in the private system. A promise to develop ‘community nursing units’ for older people was abandoned in favour of the continued expansion of tax-supported private nursing homes; extending private provision of homecare has been favoured above the development of the public home help system.7

It would not be true to say that the Irish health system is inching towards an American-style for-profit system: no, it is going there in giant strides. This development has occurred steadily, and stealthily, with no substantial public debate, no Green Paper issued to indicate the change in policy, and no honest admission that the 2001 Health Strategy, which promised a quite different approach, is no longer national policy.

Where is the Will to Change?

When brought into the public domain, individual examples of people’s suffering as a result of the two-tier nature of Irish health care, or indeed of that other serious structural inequality in the system, namely regional disparities in provision, invariably provoke outrage and anger and calls for government action. But these periodic outbursts of concern have not translated into concerted pressure for change; the recent election campaign showed that in the end neither people nor politicians were prepared to give the creation of an adequate and just health system the priority it merits. Despite our claims to ‘be good Europeans’ we seem reluctant to look to what can be learned from European social health insurance models of health care. A study commissioned by the Adelaide Hospital Society, published in 2006, showed that a system of social health insurance would be feasible in an Irish context.8 However, the creation of such a system would require a paradigm shift, so that we would come to see health care as a fundamental human right held equally by all people – one not qualified by income or determined by which part of the country a person happened to live in.

It may be incongruous that the US should rank so poorly in its provision of health care. But it is just as incongruous that, Ireland, a country that prides itself on its achievement of independent nationhood after centuries of colonisation, that relishes its economic prosperity gained over the past decade, and that is proud to be a republic, should tolerate what is happening in its health service. For not only do we seem to be resolutely hanging onto a system that is designed to treat people unequally – that is, in essence, a twenty-first century embodiment of a nineteenth century Poor Law mentality – but we seem increasingly willing to turn what should be a service that cares for people when they are at their most vulnerable into a profit-making industry.

Towards the end of Sicko, Michael Moore, issues a challenge to his fellow Americans about their country’s health care system, by asking: ‘Who are we? Is this what we have become?’ Irish people looking at their own health system could well do with asking – and answering – the same questions.

Notes

1. In 2004, the United States’ GDP per capita (US dollar purchasing power parity) was 39,676, whereas Cuba’s was estimated to be 5,700. (UNDP, Human Development Report 2006: Beyond Scarcity, Power, Poverty and the Global Water Crisis, New York: UNDP, Table 1, Human Development Index.)

United States’ expenditure on health per capita in 2004 was 6,096.2 (at an international dollar rate), representing 15.4 per cent of GDP. Cuba’s total per capita expenditure on health (at an international dollar rate) was 229.8 and expenditure on health represented 6.3 per cent of GDP. (World Health Organization, ‘Key Health Expenditure Indicators’, www.who.int/countries)

2. Catholic Health Association of the United States, Our Vision for U.S. Health Care, Washington DC, 2007, p. 2. (www.chausa.org)

3. Ibid., p. 3.

4. ‘Risk Equalisation Appeal Opens’, The Irish Times, 6 November 2007.

5. Department of Health and Children, Quality and Fairness, A Health System for You – Health Strategy, Dublin: Stationery Office, 2001.

6. Theresa Judge, ‘Minor Injury Clinics May Go Private’, The Irish Times, 23 October 2007.

7. Maev-Ann Wren, How Ireland Cares: The Case for Health Care Reform, Dublin: New Ireland, 2006, pp. 230–231; 234–235.

8. Stephen Thomas, Charles Normand and Samantha Smith, Social Health Insurance: Options for Ireland, Dublin: Adelaide Hospital Society, 2006.