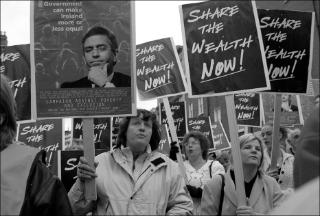

The social partnership process emerged in Ireland at a time of crisis and has been closely associated with recovery and transformation in the Irish social economy. The names of the six social partnership programmes of the past sixteen years suggest some of key concerns of the time – recovery, progress, work , competitiveness, partnership, prosperity, fairness and sustainability. The notion of fairness came more strongly into focus in recent years and the latest programme, Sustaining Progress, proposes in its vision for Ireland that the foundations of a successful society incorporates a commitment to social justice. If justice is that virtue that intends to give everyone his/her due then social justice is probably the virtue that gives everyone in society his/her due. It was clear in the run up to the agreement of Sustaining Progress that many did not think they were getting their fair dues. So clearly we are not in a position to claim that the outcomes are totally fair. In this article I will try to use traditional ideas about justice and make the case that social partnership is characterised by justice in its process to an extent that it is a practice worth maintaining and developing.

1. The Development of Social Partnership

Social partnership is a process that was grown by trial and error over the past fifty years out of the interactions, firstly of employers and employees, and secondly, of the state. Employers and employees traditionally made their deals about working together on the basis of market exchange. Labour was a factor of production, the value of which was determined by marketplace bargaining between employer and employee groups. The ideologies of voluntarism and liberalism dominated and the state did not involve itself in the affairs of business and production. The ‘free-for-all’ style of collective bargaining of post World War II Ireland was of this sort. Business and labour made their own deals and got on with providing the goods and services that citizens needed for the good life.

The business sector, however, was never very successful and the government intervened to direct its efforts. In the 1960s it set up joint committees of employer, government and employee representatives to deal with economic issues. By 1970 it had set up a joint labour conference to bring order into collective bargaining and influence the evolution of incomes. By 1980 it had involved itself in the political exchange of National Understandings whereby wage claims were restrained in return for deals on taxation and social expenditure. The National Understandings provided the know-how that facilitated the rise of Social Partnership agreements in the 1990s.

This rather brief account of the evolution of social partnership slides all to easily over the learning by trial and error that took place over long periods of time. Learning takes place through a cyclical process of analysis, planning, implementation and review in which new insights are gained, new practices planned and failed ones discarded. In so far as the developing process is a caring, intelligent, reasonable and rational approach to finding solutions to complex and many-sided problems it is an ethical approach and therefore just.

2. The Structure of Social Partnership

The parties to collective bargaining may be caring and rational but what they care about are their own interests. It is basic to the marketplace that people act in their own self-interest. Adam Smith tells us that it is not from altruism of the butcher, the baker or the candle maker that we can expect our dinner but from their concern for their self-interest. Aristotle begins his ethics with the assertion that all actions aim for a good and I would add that one’s own interests are goods and therefore the objects of moral decision making. Collective bargaining is about parties’ sectional interests. They enter the process to achieve their own objectives and are rightly dissatisfied if they do not achieve something they can live with. When parties conflict in their goals it is reasonable to modify demands and settle for a realistic compromise. Employers and employees are in a lose/lose situation if they cannot reach agreement. With agreement they can achieve a win/win. Therefore players respect the structure of collective bargaining even if it means that sometimes they lose.

A social structure is a recurrent pattern of interaction. It is recurrent because people enter into the interaction as a way of achieving desired outcomes. There are ways of behaving and conventions to be observed if the interaction is to issue in a successful outcome. The social structure of collective bargaining is an elaborate interaction that unfolds in stages. In the opening stage of bargaining positions are put forward, principles asserted and claims exchanged. If the parties can establish that the other side means business and can be trusted to carry it out in the right way they can move on to the next stage. In the next stage they reveal progressively more of the cards they in their hand in quest of a fit between their opponents’ requirements and their own needs. If the contours of common ground appear they can then move on to the end game of contracting, finalising agreement and drawing up programmes for action.

Without the exchange of meanings, intentions and guarantees proper to each stage the basis for confidence is not reached and the talks break down. If one side lets the other down by not implementing what the other understands to be agreed the relationship is undermined and the cost to each side risking renewed trust may be too high. The purpose of the structured process is to ensure that the goods delivered by the agreement can be reliably delivered again and again. The integrity of the structure depends on the individual must have a level of understanding that enables him/her to realise that his greater and longer term good is bound up with recognition of the interests of the other party. Thus collective bargaining is a social structure that in itself is a good of order. Social partnership is a similar but more complex structure.

3. Social Partnership as a Practice

O’Donnell and Thomas (1999) describe the model that was adopted for the negotiation of Partnership 2000. The parties to the negotiating process are the community and voluntary sector, the business sector, the trade unions and farming and rural interests. These pillars were assigned a ‘room’ each. A further ‘room’ was assigned to the peak organisations of the employers and trade unions, IBEC and ICTU respectively.

Formal discussions were conducted bilaterally between the “rooms” and the government’s negotiating team. IBEC and ICTU negotiated from their room with the government on the pay and tax elements of the agreement. Informal conversation was allowed between any of the parties. The government, the Taoiseach’s department formulated the final document of the agreement.

This model suggests the roles and relationships of the pillars to social partnership negotiations. The agreed programme then directs each group in action. Is this a method of governance of the social economy? NESC describes the government as “having a unique role in the partnership process. It provides the arena within which the process operates. It shares some of its authority with social partners. In some parts of the wider policy process, it actively supports the formation of interest organisations” (Sustaining Progress, 2003:14). The state has a role in guiding the socio-economic groups to the production of this socio-economic good. A part of the economic good consists of citizenship rights that “encompass not only the core civil and political rights and obligations but also social, economic and cultural rights and obligations which…underpin equality of opportunity and policies on access to education, employment, health, housing and social services” (Programme for Prosperity and Fairness, 2000:4). The state also has a role in redistributing this common good so that each citizen has sufficient resources to help him achieve the good life. In this consists distributive justice, namely that there is a fair distribution of the benefits of the common wealth. The state has a role in this because it has authority to tax and redistribute in the public interest.

The production of the common wealth, however, is a responsibility of the producer groups. Even where the state is minimal or as in contemporary Argentina, hardly functioning, general justice obliges individuals, producer groups and society in general to create a common wealth. The state’s role is to co-ordinate their efforts effectively to the common good. It is perhaps an overly paternalist view that holds that the “state provides the arena within which social partnership operates”. Those who find the political exchange between taxes and wages controversial express a similar concern from another angle. In a liberal democracy only the elected representative has the authority to decide on the use of the taxpayers money. Anglo-Saxon types of liberal democracies are not comfortable with such practice but interestingly German and Scandinavian democracies appear quite at home with it.

A move away from Anglo Saxon type individual market to a more neo-corporatist form of control might be read into the governments desire to “actively support the formation of interest organisations”. It appears as a practical project in the context of the voluntary and community sector where co-ordination might serve their cause. The trade unions too have benefited from a certain amount of restructuring through mergers and will try to achieve further consolidation and representativity. But there are contradictions associated with the co-option of unions into a neo-corporatist system. A central purpose of social partnership has been wages control. Incomes policy is seen as part of distribution policy as though incomes are a cost to the exchequer in the same way as social protection expenditure. Wages are an investment in production and with developments in supply side measures they have more than justified themselves in the output and profitability achieved. Under social partnership unions are in danger of not delivering the one thing their members support them for – a reasonable share in the fruits of their labour. On the other hand the standard of living of workers has increased under social partnership whereas it had decrease while nominal wages increased prior to social partnership.

What is good about the structure of social partnership is that it brings face to face the dynamics of each of these aspects of the whole structure. The roles of the various groups appear more clearly to each other along with their various entitlements and responsibilities. Through an intelligent and rational method of shared deliberation they identify problems, agree methods of analysis, reach consensus and guide the visible hand of implementation. In some aspects at least social partnership resolves the conflict between individual self-interest and the outcomes of the whole system. It enables the social partners to rise above sectional and short-term gains and, with some compromise, reach system gains that are more general and long term. But not all would agree and this gives rise to a third level question about the value of this particular social structure. Is it a good one? Can it deliver adequate outputs? Is there a more effective structure for delivering the same of more desirable outputs? To what extent is justice done in achieving the ends of the social economy?

4. How Good is Social Partnership?

The more usual evaluation of social partnership is in terms of economic achievement. D’Art and Turner (2002) present a set of economic indicators that show the period since 1987, and particularly after 1994, to have been one of continuous and rapid growth in the Irish economy. Real national income increased by 54% between 1987 and 1996 compared to an increase of 7% between 1980 and 1987. Unemployment reduced from 17.5% in 1987 to 6.2% in 1999. The number of people at work increased by 41.7% between 1987 and 1998. In the same period the gross average earnings of workers increased by 17.5%. When these trends are compared with the corresponding ones for the period 1980 to 1987 there is no doubt that social partnership has been associated with a remarkable improvement in national economic performance.

It is a common complaint, however, that the increased national wealth is not reflected in any easing of their economic burden for many people. D’Art and Turner surveyed trade union members for their perceptions of which groups benefited from the wage agreements of social partnership. The findings indicated that wage earners, the unemployed and low income groups were perceived to have benefited considerably less than employers, the self-employed and the government. Employers were believed to have benefited greatly. A majority believed that wage earners had received some benefits. Many believed that the unemployed and low-income groups had had experienced no benefit. A majority believed that the wage agreements had not been effective in giving workers a fairer share of the national cake.

In relation to distribution policy Turner (2002) compares the outcomes of social partnership in Ireland with those of Sweden, which is known for its achievements in the provision of social rights and in reducing the patterns of social inequality. Countries vary in the extent to which they redistribute wealth in favour of the less advantaged and provide for social welfare. Sweden and the United Kingdom, while both having a welfare system, have contrasting philosophies as to its function. In the liberal Anglo-Saxon model the state provides a basic minimum level of security. It has discretion to decide when to intervene on the basis of the need of a citizen. It is the compensator of last resort. Wealthier citizens can gain advantage through spending on health and education. The Scandinavian universal welfare model emphasises social rights. Every citizen has social rights in the area of welfare, health and education. The duty to meet these rights lies with the State and it may not compromise the delivery of services required by the rights by commercial considerations. The welfare system in Ireland is generally perceived to conform to the liberal Anglo-Saxon model.

Levels of social expenditure in Ireland are comparatively very low. Ireland was ranked last in the EU table of National Social Protection Expenditure. Sweden heads it up at 32.9% of GDP, the United Kingdom comes ninth at 26.6% and Ireland 15th at 14.7%. Health expenditure as a percentage of GDP ranks lower in Ireland, at 4.55% of GDP, than in all other OECD countries.

In relation to the percentage of its people living in poverty the UN Human Development Report (2002) ranked Ireland second only to the USA in a table of 17 industrialised countries. The proportion of households and the percentage of persons in those households below 40 per cent, 50 percent or 60 percent of mean equivalent household income all increased. Absolute levels of poverty, however, are declining and mean household income is growing. If benchmarked against its own history Ireland shows progress. A combined measure of relative income and deprivation shows a decline, particularly since 1994.

A term of comparison based on the size of household income is income inequality. Out of sixteen OECD countries Ireland ranked third highest in the level of income inequality with only the US and Italy having higher levels. CORI (2003:30) quotes a study that shows the gap between the top and bottom 20% of households widening over the past eight years.

In addition, Ireland has a high proportion of low paid workers relative to other OECD countries. The proportion of low paid workers increased from 18 per cent in 1987 to 21 per cent by 1994 making Ireland second only to the US in terms of low pay.

Overall it can be said that Ireland has made some progress when compared to its own past in areas such as poverty, general standard of living and social expenditure. But it has not reduced the inequalities that have always existed in household incomes and individual earnings. And it has not improved its position in comparison with other Western countries.

Ireland’s type of social partnership has been described as a liberal & competitive form. Its purpose is to maintain social cohesion and a cooperative workforce while the economy takes liberal measures to maintain competitiveness in the international market. The main winners are the best market performers. The overall effect is to preserve the existing social and economic status quo of society. By contrast, Sweden’s type is a strategy informed by concepts of citizenship and civic rights and inspired by solidaristic values.

Some optimistically suggest that the Irish system is on the way to becoming more like the Swedish system. However, the system properties of Irish social partnership still include pronounced inequalities, no change to the status quo, a redistribution of industrial surplus in favour of profits over wages, inflation, and increased house prices, the latter being possibly fuelled by a redistribution of wealth in favour of the already well off. Class structure continues to be a determining factor for life chances. Basic issues such as citizen’s rights in a social economy as against individual performance in a flexible market are at stake and make up the Boston versus Berlin debate.

6. Conclusion

Social Partnership has brought benefits. If the question of justice is about the distribution of burdens and benefits it must be asked who pays for and who benefits from social partnership. As a generalisation I would suggest that those who have carried the bulk of the burden and received a modest share of the benefits are workers. Those who have benefited least are some parts of the voluntary and community sector. Those who have benefited most are the large companies in the profitable sectors. The bias of benefit has been in favour of the better off. The fairness of the outcomes should and are being debated in detail and at length. The concern of this article has been about the justice of the process.

General justice is about the socio-economic effort and the generation of a common good. Social Partnership has contributed greatly to the efforts of the producer groups in this through its concern for modernisation, partnership and supply side policies. Distributive justice is a measure of the redistributive policies of the state that address the requirements of all the people for support in achieving their lifegoals. Huge progress has been made in this area if only indicated by the voice and organisation of the voluntary and community sector. Convincing arguments are made that a broader tax base is needed if the cycles of deprivation are to be interrupted finally and forever in a traditionally poor Ireland. Commutative justice is done when employers and employees agree on wages for work for a specific duration. The distributive aspect of such agreements is respected when workers are willing to take into account the effects of wage increases on the capacity of the system as a whole. Social partnership appears to have handled this with a minimum of conflict. The period of social partnership has coincided with a period of low strike statistics.

In a time of economic buoyancy it is easier to reach voluntary agreement on partnership programmes. In a time of recession pressures reduce the wiggle room and conflicts of interest appear. The present is such a time but the new agreement Sustaining Progress has been endorsed by a 60:40 margin. Many votes favoured endorsement simply because a preferable alternative was not available.

The social dialogue of adjacent rooms that facilitate conversations under the forms of discussions, consultations, negotiations and shared deliberation leading to joint decision making and coordinated action is a way of getting problems onto the common agenda so that common analysis and common solutions be found. It is a framework process of natural justice that learns the ways of justice through shared insight, judgment and action

Reference

- Turner, T. 2002. “Irish Corporatism in Comparative Context” in D.D’Art and T.Turner. Employment Relations in the New Economy. Dublin: Oak Tree Press.

- D’Art, D. and Turner, T. 2002. “Corporatism in Ireland: A view from Below” in D’Art, D. and Turner, T.

- O’Donnell, R. and D. Thomas. 1999. “Partnership and Policy Making” in Kiely, G., O’Donnell, A., Kennedy, P. and Quinn, S. (Eds). Irish Social Policy in Context. Dublin:UCD Press.

- Government of Ireland. 2003. Sustaining Progress: Social Partnership Agreement 2003-2005. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- CORI, Justice Commission. 2003. Achieving Inclusion: Policies to Ensure Economic Development.,Social Equity and Sustainability. Milltown: CORI, Justice Commission.

- United Nations Development Program. 2001. Human Development Report – 2002. NY: UN Publications.

- NESC. 1999. Opportunities, Challenges and Capacities for Choice. Report No.105. Dublin: NESC.