A tsunami does not just appear unheralded. Following an earthquake on the seafloor, inhabitants along the coast may receive one of two warnings before the waves arrive. Inundation in the form of a rapidly rising tide can precede the tsunami waves hitting shallow water. Alternatively, drawback is the less well-known warning sign as the shoreline is dragged back dramatically, exposing parts of the shore usually under water, sometimes stranding marine animals and vessels.

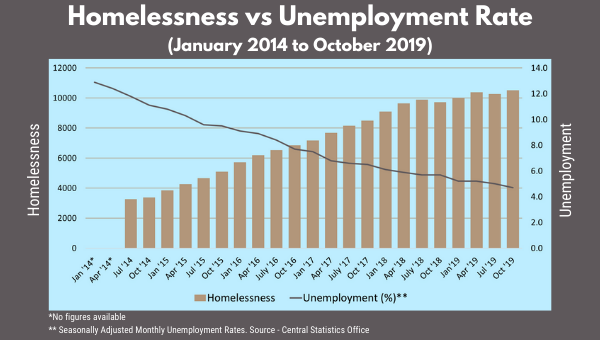

In May 2014, recognising the warning signs of a pending surge in homelessness due to evictions and rising rents, Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice social advocate, Peter McVerry SJ adapted this hydrological term for the crisis he saw coming. When he first talked about the coming tsunami, there were about 3,250 homeless people in the country and this language appeared fanciful and pessimistic. But less than five years later the number of people without homes exceeded the 10,000 mark (in February 2019). It had hovered around that figure for a year beforehand and has not significantly reduced in the period since (and as JCFJ analysis has shown, the temporary reductions that did occur were never going to last).

Despite assertions to the contrary, the Irish Government’s Rebuilding Ireland plan has failed. In this light, McVerry’s language of a devastating tidal wave seems too gentle. After all, a tsunami eventually recedes.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic affected our lives, increasing rents in the private rental market stalled in the first quarter of 2020. After 29 consecutive quarters, over a total of seven years, maximal return had been extracted from tenants. This plateauing of rents was acknowledged as a sign of success. Rent pressure zones were said to have finally fulfilled their stated intention. Last month, rents decreased by 2.1% compared to March, attributed to increased supply due to Airbnb properties being returned to the domestic rental market. Rents are predicted to continue to decrease as the Irish tourism industry has stalled due to wider public health concerns.

Following initial hesitancy and prevarication, the Government passed emergency legislation in March which contained two primary measures – a rent freeze and a ban on termination notices – to ensure people would be able to remain in private rental properties during the Covid-19 crisis. The swiftness of the passing of the emergency legislation drew a wry smile from the many housing activists who had been told for years that such a ban would be “unconstitutional”.

From the shoreline, these changes – falling rents, rent freezes for households, a ban on evictions, and increased supply – in the past two months look like the waters are finally receding. As the Covid-19 crisis is brought under further control, renters might start hoping for a brighter future. But any joy must be tempered with caution. The devastation will return. Instead of a tsunami, this moment is the eye of a storm, a tranquil moment which can appear to herald peace, but is just an interruption before further chaos descends.

Renters must remember that no structural changes to the private rental market have occurred. By definition, these emergency measures will not have a lasting effect. The ban on evictions and imposed rent freeze are time-limited to an ongoing review by the Government. Without a revolution in regulation, Airbnb properties will likely return to the short-term letting platform once international travel and holidays resume.

The position of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, currently in government formation talks, remains effectively unchanged from the past decade. Provision of housing needs will be met primarily through the private market. Subsidisation of rentals in the private market has a budget of €768 million in 2020 through the Housing Assistance Payment, Rental Accommodation Scheme and Rent Supplement schemes. Before the pandemic, the Government had set aside funds to pay over €2 million each day to private landlords. No steps have been taken that imply this will not be needed after the pandemic.

What is different in May 2020 compared with 2014? Unemployment figures are currently at the highest level since the figures were first published 37 years ago. Last month, the unemployment rate was 28.2%. To put this in perspective, the highest rate of unemployment following the Great Recession was 16% in 2012. As the predicted tsunami of homelessness arrived with total numbers more than tripling and family homelessness increasing by 349% following McVerry’s prediction in 2014, it is notable that this occurred against a backdrop of falling unemployment, from 12.9% in January 2014 to 4.7% in October 2019; the crest of the wave.

Mounting personal debt for renters, in the form of rent arrears, will be the driving force of the next round of homelessness. While little data currently exists, housing charities are warning of a swell in termination notices for rent arrears once the emergency period and the ban on evictions is lifted. Even with likely decreases in rent levels, the high level of unemployment will make it impossible to clear these debts.

Women are disproportionately impacted by the first round of Covid-19 redundancies, which has stark implications for families who were struggling to make ends meet when times were good. Compared with 2019 employment numbers, the sectors with the highest proportion of workers in receipt of the Pandemic Unemployment Payment is from the Accommodation and Food Industry. These workers are most dependent on the private rental market, with almost 40% renting.

Aside from the economic and employment devastation precipitated by the pandemic, there is another factor which has permeated and embedded itself within the housing rental sector since 2014. The expectation of increasing returns on rental property year-on-year. The previous Irish Government clearly demonstrated its preferential option for the investor, both small and large. Investment funds purchased 95% of the 3,644 apartments completed in Ireland last year.

As rents soared in recent years, the Government responded with a hastily devised policy of Rent Pressure Zones. These regions spread so widely that we reached the absurd position that over two-thirds of Irish rental properties were included. Dublin and Galway’s city centres were included, but so too was Macroom. It was a sticking plaster for a sector in deep distress. Instead of reducing rents, Rent Pressure Zones had the effect of creating a floor under investments where investors could plan for returns increasing by a minimum of 4% on a biannual basis.

The warning signs for this new tsunami of homelessness look different. At the moment, the waters may be retreating for private renters as rents decrease and supply increases. But lack of structural changes, increasing rent arrears, coupled with previously unseen levels of unemployment, and stubborn investor expectation, augur havoc.

Public emergencies of the magnitude of the Covid-19 pandemic require creative solutions to help people survive and recover. The existing neoliberal playbook is useless in the face of this problem. Any policy solution which imagines us as isolated individuals, when the virus exposes our profound interdependence, must be rejected.

When a stranger contracts the virus, it affects us. When a stranger is made homeless, it affects us. Mechanisms to cancel rent arrears need to be explored and prepared in advance to allow people to restart their lives. We need a wholesale commitment to public housing and a dedication to use public land for that purpose. And as Peter McVerry told Pat Kenny on Newstalk this week, we need a reordering of our priorities so that a home for everyone in this country is available to them.

When drawback occurs, the tsunami follows quickly.