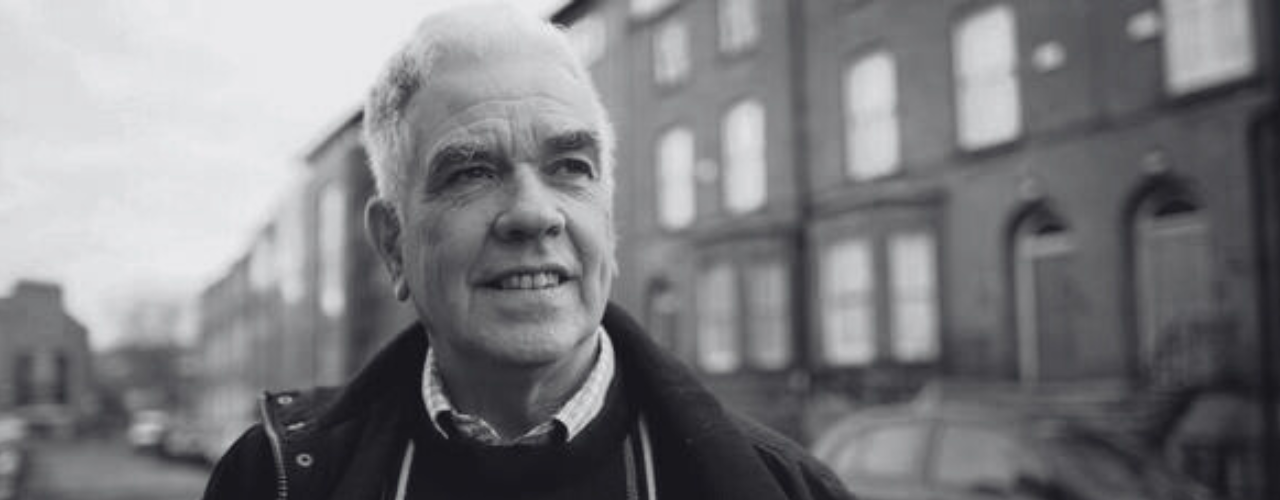

Peter McVerry SJ reflects on the futility of the continuing ‘war on drugs’ in Ireland and why the money that is wasted in the punishment of drug users would be better spent on education and treatment.

The Neverending War

In 1974, a Japanese soldier, Hiroo Onoda, was found hiding in the jungle in the Phillipines. He had not realised that World War II was over. Twenty-nine years after the war had ended, he was still trying to avoid capture so that he could continue the fight. His predicament was so weird that every news media in the world covered the story.

However, no less weird is the war on drugs. Like Onoda, this war has been going on for over thirty years and we have lost. But we continue to fight in the belief that the war still goes on and can yet be won. Over the last three decades, we have used the criminal justice system and spent billions of euros in trying to reduce drug use; enacted tougher and tougher legislation; and imprisoned tens of thousands of drug users. And the result?

We have an increasing supply of an increasing variety of drugs, to an increasing number of drug users, in an increasing number of cities, towns and even villages of Ireland. With “value for money” being the ubiquitous political catchphrase, it is difficult to argue that the billions of euros spent in the criminal justice system on trying to reduce drug use has been good value. There is now, in this country, a free market in drugs. We sometimes call them, without realising the irony, “controlled drugs”, when the reality is quite patently the very opposite. In many areas, you can have your drug of choice delivered to your door quicker than a pizza. And it will be delivered by a 13-year old on a bicycle who is starting off in his career.

Illegality, Not Usage, Links Drugs and Crime

In any discussion on drugs, we have to acknowledge that the drug that causes most damage to the individual, the family and the community is alcohol. But the possession and use of alcohol is not a crime. Of course, some people will abuse alcohol which may lead to criminal behaviour, such as assault, damage to property and so on, but that is due to an abuse of alcohol, rather than the use of alcohol itself.

Contrary to what common sense may suggest, there is no intrinsic link between drug use and crime. The link is artificially created by us, by the attitudes of many in society and the policies which Government enact, or fail to enact, in response to those attitudes. We have also created an artificial distinction between legal drugs—such as alcohol—and illegal drugs. And it is the illegality of drugs—a social construct created by society—not the use of drugs which links drugs and crime.

Why can you walk down the street with a bag full of beer cans without being arrested but if you have a small bit of cannabis in your pocket, you can be arrested, prosecuted and criminalised? Many young people will say that our society is hypocritical, that no-one has ever beaten up their partner or smashed up their home, or terrorised their children, while under the influence of cannabis. Yet the possession of a small amount of cannabis is a criminal offence, while society allows every second shop to promote alcohol, sell alcohol and the government makes a lot of money from alcohol sales.

Different Drugs, Same Motivations

When we criminalise the use of some drugs, there is a danger that we demonise drug users, that we consider them to be bad people, with a different motivation and pattern of behaviour to the rest of us. In reality however, if we want to understand why people take what we define as illegal drugs, we only have to go down to any pub, any evening, and ask the adults what they are doing there. They will say that they are there to relax, to socialise, to escape the pressures of life, to alter their moods.

Many people take illegal drugs for exactly the same reasons. People take alcohol because they enjoy alcohol. Many people take drugs because they enjoy taking drugs – drugs alter their moods in a way that nothing else seems capable of doing as effectively. Drugs help them to relax and to escape from the pressures that they feel in their lives. Taking drugs is a pleasurable experience, just as taking alcohol is a pleasurable experience.

Moralising Obscures the Problem

If a climate of fear dominates most public discussion of drug policy, it is often associated with, or justified, by a climate of moral disapproval – drugs are bad, therefore we must eliminate them, we cannot be seen to tolerate them in any way. The war on drugs must continue and any dissenting voices must be suppressed.

Unless we can discuss all possible responses to the problem of drugs in a rational and open-minded way, then we are doomed to continuing what we have always done, even though that is clearly inadequate. The most important task at the moment is to begin to create a climate in which our society can look objectively at the drug problem and the effectiveness of different responses, without being censored by moral disapproval or panic reactions.

Instead of making a distinction between legal and illegal drugs, which is unhelpful to the point of obscuring the problem, it would be more helpful to make two alternative distinctions:

- To distinguish all drugs by the harm that they cause to the individual, the family and society.

- To distinguish between drug use and drug misuse, whether legal or illegal.

Recognition of Harm

To abandon the distinction between legal and illegal drugs, and focus on the harm which drugs cause, involves a fundamental change in our attitudes. However, most people are too afraid of what we call illegal drugs to be able to discuss them rationally. Many parents, if they become aware that their child has experimented with drugs go into panic mode. They have visions of their child destroying their life, possibly going to jail, or even dying from drug overdose.

In such a climate of fear, no discussion of drug policy can take place – parents want desperately to protect their children and any discussion of drugs that does not promote strict criminal justice policies which pursues the elimination of drugs – despite the impossibility of achieving that objective – will not be tolerated. Alternative policies are dismissed before they are even considered. The irony is that if their child is caught using drugs, they actually don’t want their child to be prosecuted and have a criminal record for the rest of their life, they want help and treatment for their child.

Understanding Drug Use and Misuse

Drug use is drug taking through which harm may occur, whether through intoxication, breach of laws or of school rules, or the possibility of future health problems, although such harm may not be immediately perceptible. Most adults in the pub at night are using drugs, not misusing drugs. Similarly, not all illegal drug taking is drug misuse. Most people smoking cannabis or snorting cocaine are not misusing drugs. They may harm themselves. Cannabis today, which is far stronger than the cannabis of the 1980s, is causing major mental health problems and cocaine may bring on a heart attack, but they are not causing a problem for anyone else, except possibly themselves.

Drug misuse is when drug taking harms the functioning of the individual or creates problems for their families and for society. Adults who are heavy drinkers, causing serious damage to the harmony of their families, are drug misusers. Similarly, some people’s drug taking is causing serious problems for them, their families and their communities. This demands a totally different response from our response to drug use.

The misuse of legal drugs such as alcohol or prescription drugs is considered primarily as a medical and social problem and dealt with accordingly. We refer people for counselling or rehab. Being drunk is not a criminal offence, unless it presents a problem for others.

With Just a Hammer, Everything is a Nail

However, both the use and misuse of illegal drugs, on the other hand, is primarily dealt with as a criminal justice issue. Society’s efforts to reduce the use of illegal drugs through the criminal justice system has been a total failure. Not only does it waste enormous resources, processing people who have been caught with small quantities of drugs for their own use, but it is counter-productive: it introduces them to a criminal sub-culture and through the societal consequences of having a criminal conviction (difficulty of obtaining employment, difficulties of obtaining visas to travel and the labelling that a criminal conviction ensures) marginalises people even more in their society and that is a major factor in pushing them into further criminal or drug-using activity.

In a Queens University Belfast survey some years ago, 40% of 15 year olds admitted to having smoked cannabis at some time in their short life. I presume, in an ideal world, many would like to see a 100% detection rate for criminal acts – in such a scenario, then, 40% of the children of Ireland would grow into adulthood with a criminal conviction. The first to raise their voices in protest, and rightly so, would be their parents. Non-problematic drug use should have nothing to do with the criminal justice system. Our response should be based on prevention and treatment, that is to say, education about drugs, counselling where it is requested, residential treatment and social care where necessary.

We Can’t Punish Our Way Out of Drug Misuse

Drug misuse should also have nothing to do with the criminal justice system. Of course criminal acts associated with drug misuse, such as assault, robbery, theft and drug dealing, are appropriately dealt with by the criminal justice system. But responsibility for drug misuse, in itself, should be transferred from the Gardai and courts to the Department of Health. This means “medicalising” drugs, not criminalising their users. It involves seeing drug misuse as a health issue, which requires support and treatment, not a criminal issue which requires punishment. It sees drug misusers as vulnerable people in need of help, not criminal outcasts. It means a state response to drug use that emphasises the role of health professionals and counsellors, not criminal lawyers, and thereby frees the Gardai to focus on drug dealing. However, treatment options for drug users in Ireland are very inadequate. Outside Dublin, treatment may be patchy or even non-existent. Even in Dublin, long waiting lists are common.

What It Means to Take Drug Misuse Seriously

A common argument against decriminalising drug use is that it gives a message that society does not consider drug use to be an issue of serious concern. But if we re-invest, in treatment and education, the money saved by decriminalising the possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use, we can actually give the opposite message: drug misuse is an issue of concern – but, like alcohol misuse, it is a health and social issue. By providing adequate and easily accessible community-based and residential treatment programmes, and investing in health professionals to work with drug misusers in the community, we give the far more effective message that drug misuse is bad for your health, for your family, for your community – but that help to address the problems which it causes is readily available.