The Origin Story

Eight years ago, Pope Francis published one of the most important works of environmental thinking in history, Laudato Si’. Praised by religious and secular figures alike, it had an immediate and lasting impact. It was written to engage the scientific, political, and religious communities – addressed really to “every living person on this planet” (§3) – and to summon us all to a renewed commitment to “care for our common home”.

Laudato Si’ are the opening words of the famous Canticle of the Creatures by St Francis of Assisi, a prayer/poem/hymn that the great proto-environmentalist wrote almost 800 years ago. It means “Praise be to you” and that captures the reverence and joy that can be found in Laudato Si’. While dealing with a topic that is so desperately important, it is marked by a profound openness to the world and a striking curiosity.

Laudate Deum Introduced

The sequel to Laudato Si’ was published today, October 4th, which is fittingly St Francis of Assisi’s feast day.

Laudate Deum’s [Praising God] continuity with its predecessor is indicated by its name. Usually with Papal documents, the opening line explains the title. But with Laudate Deum there is a coda: the final sentence brings new perspective to the meaning of the name given to the text.

Unlike the 2015 document, this is not a Papal encyclical but an Apostolic Exhortation. While both documents carry authority within the church, an Apostolic Exhortation is considered to hold less weight. “All the faithful” should ideally receive and reflect on exhortations, which typically address a specific issue. The sub-title, however, broadens that audience: “To all people of good will on the climate crisis.”

The directness of that address is continued through the body of the work. Laudato Si’ had six chapters. So does Laudato Deum. But the Apostolic Exhortation is much shorter, consisting of a ’long-read’ length of about 8,000 words compared to the book-length of Laudato Si’s 40,000 words.

After an introduction, Francis considers the present state of the crisis in the opening chapter, before retrieving and deepening a key argument from Laudato Si’: that we suffer many of our present problems because of what he calls our “technocratic paradigm”. Chapters 3-5 are where the pointed element of this document become clear. He articulates the weakness of international political institutions in chapter 3, gives a brief history (sadly underwhelming) of the COP meetings in chapter 4, and points us in chapter 5 towards the upcoming COP28 meeting in UAE and insists that “to say that there is nothing to hope for would be suicidal” (§53)!

The argument that you might expect to find at the beginning of a teaching from the Holy Pontiff actually comes at the end as in chapter 6, Francis lays out the “Spiritual Motivations” for climate care. Practically, what this means is that the text can be read by a scientist, policy expert, or politician who has no Christian commitment or any religious belief at all and make sense. Surely there will be some critics who feel that this is Francis marginalising the theological content of Christianity, but a generous reading will quickly find that this section is remarkably robust and that that final sentence demonstrates not a shred of embarrassment about why praising God must be central to our lives.

What is the Goal of the Document?

In the Introduction, Francis explains that he has to write, eight years on from Laudato Si’, because thus far “our responses have not been adequate” and the environment is now hurtling towards a “breaking point” (§2). We must care about this because it is a “global social issue and one intimately related to the dignity of human life” (§3). Human dignity is one of the pillar ideas in Catholic thinking about society. Through this opening reference Francis is speaking in terms that anyone can understand – “human dignity” is also a pillar concept in EU law, but he is also deploying a term with profound theological resonances. While citing Christian documents from around the world, he agrees with the African bishops, that Climate change “makes manifest ‘a tragic and striking example of structural sin’” (§3). On a basic level, the intention of this document is to “clarify and complete” the work begun in Laudato Si’ (§4).

But the document is clearly written to inspire the delegates who will attend the COP28 meetings in Dubai in December. He carefully lays out how previous COPs concluded with high hopes that have never quite delivered. The reader can almost hear his frustration at how every year the Great and the Good gather and discuss these critical issues and every year they disappoint.

So when we think about the failures of Kyoto and Paris and Copenhagen and Glasgow, what hope can we have for a meeting hosted by the oil-rich Emirati states? But Francis reminds us that humans can always change and humans have collaborated successfully in the past (thinking specifically of the repair to the OZONE layer (§55)).

In paragraph 60 we find the real goal of the document: He calls on those attending COP28 to be strategic in their participation. Strategic here doesn’t mean self-interest, or even the interest of their own nation or region. Instead, he defines it in terms of the common good and the future generations. On a matter of such grave significance, those who go to negotiate must remember that they will be remembered. “What would induce anyone, at this stage, to hold on to power, only to be remembered for their inability to take action when it was urgent and necessary to do so?”

We will know that COP28 is a success if it generates a binding commitment to an ecological transition that is “efficient” (by which he seems to mean something like effective), “obligatory” (unlike previous COP agreements) and “readily monitored” (to stop the free-rider problem) (§59). Such an agreement would be drastic, intense, and demand the commitment of all nations.

But without it, what do we face except “the real possibility that we are approaching a critical point” (§17). The only thing harder than a prompt, universal, just transition will be its alternative.

What Are the Spiritual Motivations?

Francis leaves most of the explicit theological content until the end of the document. Of course, keen readers will find robust theological content woven into the core of the argument – solidarity and subsidiarity, human dignity, the dignity of work, the universal destination of goods and the preferential option for the poor are all there.

Throughout the document, Francis’ anger at the evasion and denial tactics of self-styled sceptics simmers below the surface. He forthrightly rejects those who “deride these facts” about the climate collapse (§6), is scathing at those who push a rebranded form of Malthusianism (For them, “as usual, it would seem that everything is the fault of the poor.” (§9). And he struggles with the reality that even within the church some harbour “scarcely reasonable opinions” (§14) about the crisis we face.

In a different tone, this last chapter echoes this refusal to credit fantastical thinking. Environmentalism is not an optional extra for super-holy Christians. It is not a niche interest that some cultivate and that the rest must tolerate. “I cannot fail in this regard to remind the Catholic faithful of the motivations born of their faith” (§61). In a series of hard-hitting paragraphs, Francis outlines how the Scriptures testify to how the world in which we find ourselves is lovingly created. Jesus – the one whom Christians believed created and sustains everything – is a man deeply at home in the natural world who directs our attention to the birds of the air and the lilies in the field, not as some private spiritual devotion or a sentimental distraction from our difficulties but because the Resurrected one is the one who is making all things new.

Throughout the document, Francis takes every opportunity to alert us to how we are formed to treat the world as an instrument to be exploited for our gain. This is what he means by the technocratic paradigm – we start thinking about “natural resources” and end up treating everything – even ourselves – as a resource, as an inefficiency to be honed, as a problem to be solved. Instead of a gift we receive on loan, we end up treating the world like our own private property. And in the final paragraph he turns back to that theme to explain why it is so important that we make “Laudate Deum” a practice in our lives: “When human beings claim to take God’s place, they become their own worst enemies.”

Conclusion

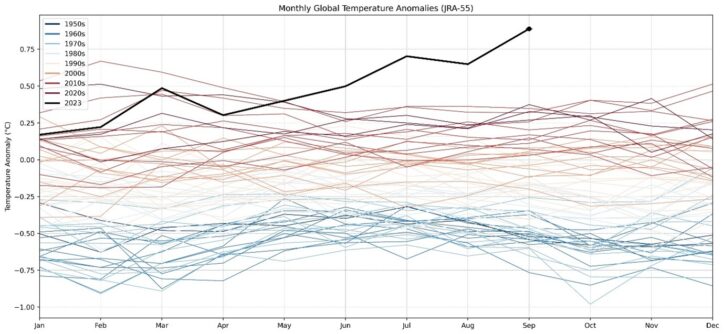

At around the same time as this exhortation was published, many of us saw the data for September’s global temperatures. As that line breaks free from the mass of previous years and reaches for heights never before seen, it is hard not to empathise with Francis’ furious impatience.

Lament is an appropriate response. Francis admits as much when he invites us on a “pilgrimage of reconciliation” (§69). It is hard to conceive of reconciliation without lament and repentance. But the overwhelming message of this document – directed as it seems to be at diplomats gathering at an international conference – is that “the most effective solutions will not come from individual efforts alone, but above all from major political decisions on the national and international level” (§69).

Francis never tires of telling us that “We are all connected” and “no one is saved alone” (§19). Let us hope those who represent us at COP28 remember these truths.