Richard Carson

Richard Carson leads ACET Ireland – a gifted team of ten staff and a few volunteers responding through a range of projects to migrant health, community addiction and HIV. His walking tours on themes of race, place and theology along Lower Gardiner Street and its surrounds have featured on RTÉ Lyric FM, Culture Night and with numerous schools, colleges and community groups.

“The breath of God brooded over the waters”. Genesis 1:2b

On 9th May 1914, just weeks before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and sandwiched between the Larne and Howth gun-runnings, The Irish Times published an editorial entitled “Disused Churches”.1 The article was the announcement of the closure of Trinity Church on Lower Gardiner Street, a venue that had, in the mid-19th century, been packed with thousands of worshippers every weekend and was later described as a “citadel of Protestantism.”2 The editorial is a remarkable piece of writing. Declaring “no spiritual tragedy”, it assures the reader that there is little to grieve at the seeming decline of the north-east inner-city congregation. The people were merely heading to “the pleasant suburbs” and the tram lines would lead them there. The writer’s disregard for the declining North-East Inner-City as a place of life, need, and hope could not be more stark and the patronising nadir comes with a quotation from Bishop George Berkeley: “Westward the course of Empire takes its way.” Berkeley’s prose, including this particular line, had profoundly shaped the idea of manifest destiny – that

the United States of America’s expansion and conquest was a blessing and directing of God. But for The Irish Times, “westward” was not the plains of Colorado nor California but rather the likes of Castleknock.3 “The movement of modern cities is from the centre to the circumference” states the editorial with confident certitude, as the reader is left with little sense that there is any remnant of connection between the Trinity Church congregation and the place they leave behind.4

In this essay I will explore how the understanding of place at work in this move from the centre to the suburbs has been formed in the setting of colonial modernity. I will go on to show how this understanding is not limited in impact to geography, but also informs how we tolerate the division of wealth, as well as the way we share the story of a place. We cannot make sense of the challenges and

opportunities facing the North-East Inner-City today without understanding how these streets

came to be. As such, it will be the streets of the North-East Inner-City of Dublin which will

concern us. I will then use a rarely discussed environmental and health issue in the area – air pollution – to illustrate how the connection of the suburb and the centre is, despite our best efforts, inescapable. I will conclude with a brief afterword about a phenomenon at present day Trinity Church on Lower Gardiner Street that reconnects our imaginations of the past to the future.

PLACE

The Yale University theologian, Willie James Jennings, offers us an understanding of the way of thinking about place and our shared lives together which is at work in the announcement of the Trinity Church closure. His contention is that from the late medieval period, “race” rather than place became the defining feature of one’s identity in the world.5 The land from which one found meaning was no longer relevant, so its riches could become commodities for the Empire as the modern colonial era emerged.

The constructed idea that skin colour was not merely a biological differentiation but a social and political categorisation allowed for a racialisation of humanity. This loss of land as identifier was not merely an incidental factor in the emergence of “race” but a fundamental dis-place-ment in how we view the world and our relationship to it. Place could now become something one found oneself on rather than where one was found in. This redefined our interdependence within the world and thereby allowed the likes of the Trinity Church congregation to move to the pleasant suburbs without consequence or regret. Note that it was not merely that the editorial exhibited a lack of care or concern for the North-East Inner-City.

That can be assumed. The key issue is that the congregation were so thoroughly dis-placed from the ground beneath their feet that such care or concern was impossible.

Jennings cites the great Native American religious scholar, Vine Deloria Jr., in saying that the colonial move “drained the world of its spatial realities. Native peoples were forced to think their lives temporally and not spatially.”6 Where you are moving, growing, developing toward (temporal) is far more important than where you live, share, experience life with the land and one another (spatial). This is the

imagination that still holds sway. This move of displacement, according to Jennings, was first and foremost a theological one, led by European colonial powers looking to justify their understanding of how God was at work at the encounter of the so-called ‘old world’ with the ‘new world’. It was not merely a reorientation of identity but an engagement and application of the power that those colonial nations wielded, and so Christian theology, Jennings suggests, must engage with this story of power in place.

While the imperialistic tone and political setting of the editorial may seem distant to current readers, Jennings would argue that the story of displacement and its infection in our imagination is very much still with us today. On 3rd December 2023, in the shadow of the Dublin riot just 10 days earlier, The Irish Times published an editorial about Lower Gardiner Street and the “two city blocks” that include

Trinity Church. Some of its text eerily mirrors the 1914 editorial, though in a very different political context:

The truth is that ever since independence successive administrations – and by extension the people who elected them – have treated the population of Dublin’s inner city with suspicion and disrespect. From the tenements of the early 20th century onward, people who generally live in the comfortable suburbs have made decisions that affect the lives of those who live in the centre. Too often those decisions

have been misconceived. Sometimes they have been disastrous. 7

NEED

The “pleasant suburbs” of the 1914 editorial may now be described as “comfortable” but the story is the same. Indeed, over 100 years on a further demonstration of displacement can be seen in the landscape of the area.

The 1980s brought an attempt to reinvigorate the then dilapidated north city docklands through the creation of the Irish Financial Services Centre (IFSC). Special low-tax arrangements allowed many of the world’s leading banks and financial institutions to find a corporate home in the area. While the IFSC’s

impact has extended downstream and across to the south-side, the companies represented in the IFSC and within the boundaries of the NEIC8 (by my own back-of-the-envelope calculations) have assets worth about €2 trillion. They are rarely if ever understood as being a part of the NEIC. They operate on,

but not in, the NEIC. It is worth remembering that displacement not only delivers an altered and fragmented view of the land. According to Jennings, it also fragments our understanding of need such that the possibility of imagining needs together is eroded.9 Needs, even those as simple as shelter, food, and safety are fragmented all the way down to the individual. And so, the fragmentation of need and place, established in the colonial period, now finds its fulfilment within the story of the NEIC as wealth is so spectacularly divided by a matter of a few feet. The tall ships carved into the south pediment of the Custom House are in full sail as prevailing winds carry the bounty of global trade to the North-East Inner-City. “Commerce” is the name of the statue that stands tallest on the building, yet, to this day, the generated wealth immediately fragments on arrival at the docks. It is in this light that Fintan O’Toole, seeking to make sense of this part of the NEIC, described it in both material and geographical terms as

“Ireland’s most segregated district.”10 Jennings puts this in devastating theological terms when he states that: “Every time you go from one neighbourhood and enter another and see inequality and say ‘that is the way it is’ you are calling that which is demonic, natural.”11

A piece of World’s End Pottery, named after World’s End Lane (now Foley St) where it is believed the Delamain family lived. They established their delft factory as Hugenot refugees, at the corner of Frenchman’s Lane, a site now opposite Store St Garda Station. The photo was taken in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, July 2022. Credit: Richard Carson

STORY

Not only fragmenting our understanding of need and place, displacement also fragments our stories – disconnecting us from one another and giving the appearance that the story of the NEIC is merely its own. But the NEIC has always been shaped by what is outside of it. While, as the human geographer

Doreen Massey was right to remind us,12 the local carries agency and accountability, it is the global which both carries the impact and is easily overlooked. So it is crucial that we are able to tell and share our stories of the area. Without them we will fall for that trap of temporality that keeps us from appreciating how we relate to one another in a place. As Philip Sheldrake highlights in response to Michel de Certeau’s attack on modernist planning: “Stories are more than descriptors. They take ownership of spaces, define boundaries and create bridges between individuals.” 13

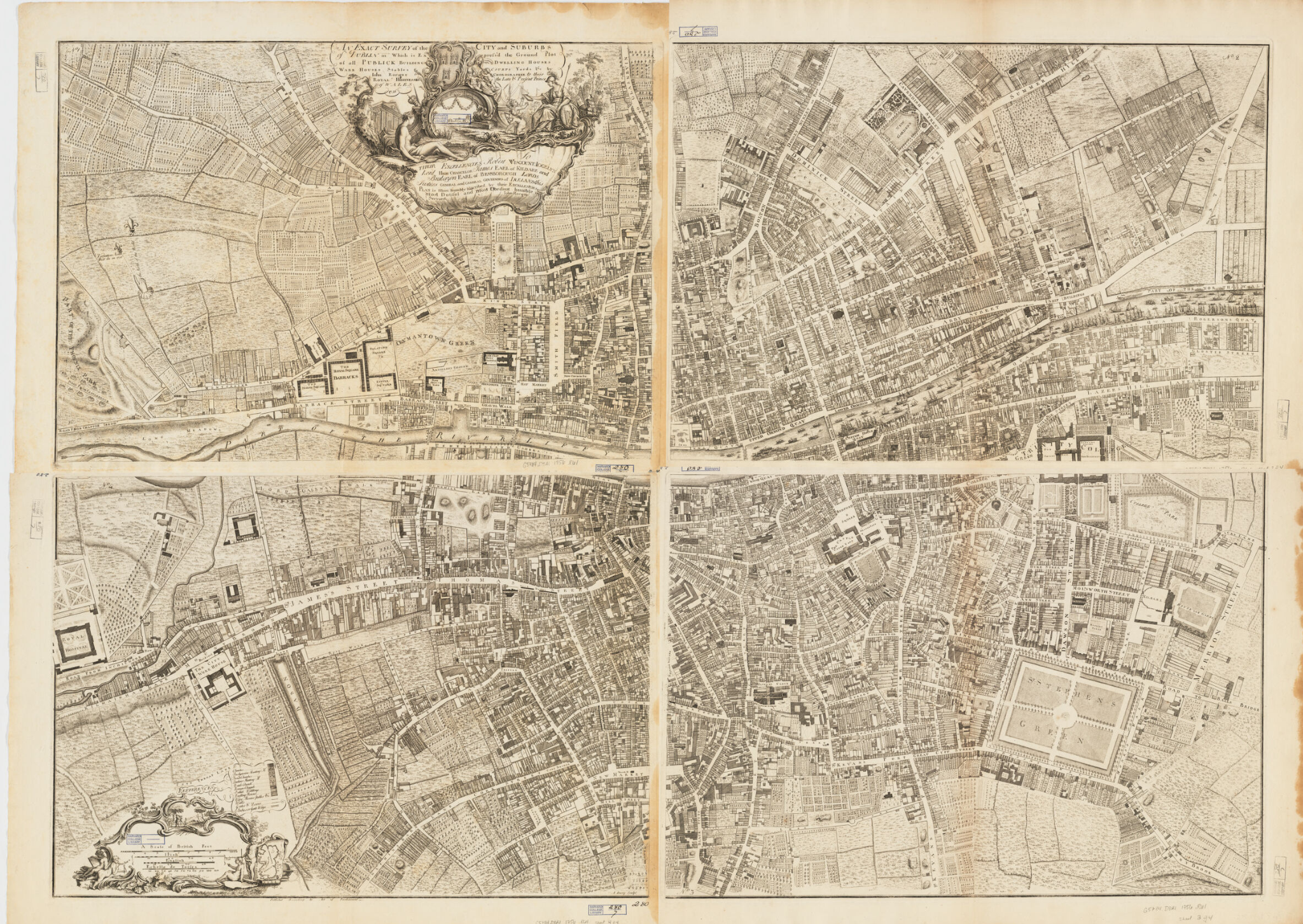

To understand the story of the North-East Inner-City we need to go back to the beginning, or at least a beginning in the early 18th century when the quay walls of the River Liffey allowed the swampy land and ponds to be steadily reclaimed. While the Gardiner family owned most of the area, the impact

of the Wide Streets Commission and the streetscape we are familiar with today were still a long way off. The land was replete with vegetable gardens and orchards. The soft soil, no doubt, demonstrating a rich biodiversity.14 Of the residents we can ascertain, there was clearly a presence tied to the recent religious

wars across Europe. Huguenots from France, like the Delamain and Du Lac families, or from Holland, like the von Beaver and von Verigan clans, occupy what is now the Foley St, Railway St and, of course, Beaver Street areas.15 The property deeds of the time, which describe the area as “a suburb of Dublin City” show the likes of Ephraim Hand, Abednego Hudson and Hosea Coates as among those living closer to what is now Lower Gardiner Street, suggesting a Jewish presence adjacent to the nearby synagogue on Marlborough Green. That synagogue was associated with families descendant from Marranos Jews who

had been forced to convert to Christianity in Spain or Portugal but continued to meet for Jewish worship in secret before seeking refuge in Ireland. This extraordinarily diverse mix of people and plants finding refuge from that which was outside is the early story of the NEIC. All other chapters in its story build on

this foundation.

The opening of the Custom House in 1791 transformed the area. John Beresford’s efforts in the parliaments of London and Dublin to gain permission for its construction massively benefited his brother-in-law, Luke Gardiner, who was building up the streets we are so familiar with today. But just four years after the opening of Carlisle (now O’Connell) Bridge (an architectural sibling to the Custom

House), the bodies of Protestant Thomas Bacon and Catholic John Esmonde were placed on display on the bridge, following their execution for their part in the 1798 Rebellion.16 Their killings took place within a fortnight of each other. At that same time, Luke Gardiner, Lord Mountjoy, was also killed,

while leading the British forces at the Battle of New Ross in Wexford. Though still nascent, the area developed an immediate familiarity with trauma which will last to this day.

Though the elite continued to dominate residency and ownership, the Act of Union of 1801 began a steady decline for the area through the 19th century. This was exacerbated when the rural poor find there

an urban home after the Famine, as their little wealth is steadily transferred from the landed gentry to the suburban landlord, via the tenements. The era of tenement housing included the emergence of ‘Monto’, Europe’s largest red-light district, which drew soldiers and sailors of far-flung lands as its

clientele. The twentieth century brought some changes, with inner-city parishes and housing

developments emerging, including the building of new outer suburbs for the working classes.17

However in the 1980s a perfect storm hit the area. A regime change in Iran opened up a trade route for heroin into Western Europe, while the trade routes of capitalism carried HIV from the opposite direction. High youth unemployment and an insipid public health response to the emerging crises devastated the area. More recently, all the facets of our housing crisis can be found within the area.

The prevalence of emergency accommodation signals another chapter of those seeking refuge on our shores being hosted in this area.

HSE Naloxone mural on the St Peter’s Bakery site on Parnell St. Installed in spring 2023, six months later the spike in overdoses took place. Credit: Richard Carson

As recently as late 2023, another global regime change is impacting the area. This time, it is the

tumult in Afghanistan, affecting the supply of heroin again. Dangerous synthetic ingredients are being added to the drug, thereby leading to a massive increase in overdoses. The mortality levels of the past were only avoided by the administration of naloxone, an opiate antidote, in dozens of settings by trained workers around the inner city. This current challenge has gone effectively unnoticed by wider society, which should in itself testify to the reality of the NEIC’s problems. The impacts of global capital flows and its financialisation of property is also being felt harshly in the area, and largely unobserved by those outside it. In autumn 2019, three churches, which were using the hall within the St Peter’s Bakery building on Parnell St, were asked to vacate the premises as the new owner had been granted planning permission to build student accommodation on the site.

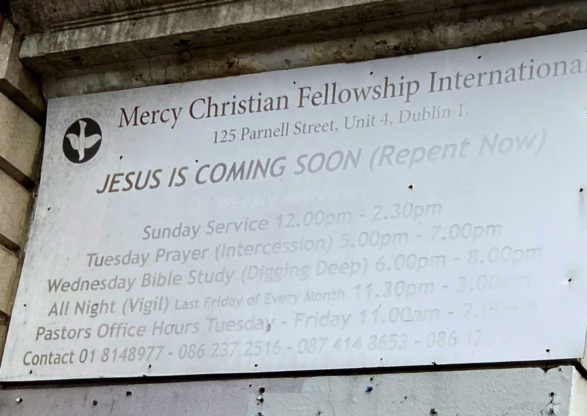

With little fanfare and no media coverage, the 700 worshippers had to find new homes at the edge of the city, where public transport access is poorer and there is greater reliance on the private car, thereby increasing the precarity of already fragile settings of diaspora life in Ireland. To this day, the faded signage of Mercy Christian Fellowship, the lead tenant up to 2019, is still in place on Parnell Street.

On the placard some words of future hope – “Jesus is coming soon” – are in conversation with the absent congregation, who moved from the centre to the circumference as history repeats itself. Whether it is New Ross, Tehran, London, Crumlin, Kabul, Blanchardstown, Boston or Berlin, the story of the NEIC is of a place defined as much by what is outside and what is within.

Engaging in such storytelling is not a task of mere nostalgia nor tepid historicity. Rather, it is to encounter the very place where we dwell. The story of how need came to divide so spectacularly in adjacent settings is no coincidence but a tangible reality best encountered with a short walk or cycle through the area. Jennings vividly, and with a sense of cautious warning, uses a meteorological metaphor to connect our present circumstances with the past: “Remember the wind, remember her voice, she knows the origin of the universe.”18

BREATHE

The opportunities to explore the connection between the NEIC and that which is outside of it are legion. Housing, healthcare provision, wealth, education, childcare and much more are all worthy of analysis. However, I want to focus in on an environmental and health issue which is often neglected in local and national debate. It shows how the links of place, need and shared story are inescapable and as immediate as the next breath we take.

The southernmost section of Lower Gardiner Street, at Trinity Church, was once Lime Street. While its etymology is uncertain, the likely reason for its name, just like the more famous streets of the same name in Liverpool and London, was the presence of lime kilns on the site in the early 18th century. With toxic and odorous fumes, lime kilns in urban settings did not last very long and were prohibited alongside glass houses and other similar contributors to air pollution. However, the area around North Wall was still a suburb of the city rather than subject to its bye-laws, and so through the 18th century it carried

the burden of production of those industries still linked to the fumes that had a profound impact on the health of the local population.

A key factor here is the prevailing wind. In an extraordinary study for the Spatial Economics Research Centre, the position of 5,000 chimneys across 70 English cities in 1880 were analysed alongside deprivation indexes.19 A clear link between the south-westerly breezes and poverty was found.

“Basically what we’ve been seeing in the past, because of pollution and wind patterns, is rich people escaping the eastern parts of town, because they were very polluted” stated co-author Yanos Zylberberg. “Past pollution explains up to 20% of the observed neighbourhood segregation whether captured by the shares of blue collar workers and employees, house prices or official deprivation indices,”20 Once set in place in infrastructure and institutions, this pollution-informed poverty becomes incredibly difficult to undo.

This image of Georgian or Victorian air pollution may seem distant to our current circumstances, as removed as a Dickensian novel. Yet, we are currently experiencing another silent killer, though this time odourless and less obvious. In 2021, following research on far-reaching evidence of how even low

levels of air pollution impact health, the World Health Organisation dramatically amended its guideline limits for a number of key pollutants.21 Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) is particularly linked to emissions from motorised vehicles and its limits were cut from an annual average of 40μg/m3 to 10μg/m3. Monitoring of air pollution in Dublin City is sketchy at best but we can clearly see how areas of heavily motorised traffic link to higher NO2 levels.22 Junctions, such as around Heuston Station, show levels over 50μg/m3. However, it is the inner city residential areas that are most noteworthy. Monitors on Pearse Street showed levels over 60μg/m3, six times the WHO limits. Gardiner Street, with a monitor adjacent to the award-winning and recently refurbished Diamond Park, with its stunning playground and landscaped terrain, came in at 50μg/m3.23 With the odd exception for a busy junction, once one leaves the inner city core, the NO2 levels drop to below 20μg/m3 – in the vast majority of places still above the WHO limits. The kilns may be long gone but the cars have taken their place.

The physics of NO2 care nothing for the lines we draw through our institutions and imaginations. Its only barrier of concern is the lining of the bronchial tubes of the children who play in the Diamond Park, and unless the initiatives of the Dublin City Centre Transport Plan and the Dublin Region Air Quality

Plan have a profound effect, the impact on the respiratory health of these children is inevitable.24 It may be that it is not so much a policy change that is required as a change in our imaginations. Where fragmentation still holds power, we need to reimagine our relationship with the ground beneath our feet

and with the lines we draw across it. “We are of the dirt!”, Jennings declares, challenging our self-designation in a place that keeps us distant from that which is adjacent.25 Regardless of how it appears, such a move would not be some new radical offering, but rather a truly conservative move – back to our relationship with place and one another. It starts, contends Jennings, with the communities that have been left behind by the lines we have drawn through cities and communities with our insistence on elevating the temporal at the expense of the spatial. To live across the lines that have formed us, with patience, presence, joy, and hope is the first and crucial step. All of these, and particularly joy, are an act of resistance against the forces that drive us to despair, the forces that keep us apart and insist that our

fragmentation, even the fragmentation of death itself, must have the last word.

Weaving through how displacement and fragmentation form, our story, our needs, and our place can seem overwhelming. We live and operate so deeply in the imagination of these forces that to escape them seems as impossible as it is to stop breathing. We need something radical. Yet for all the big picture

focus Jennings offers us in his work, it is with the small and simple that he believes we must start. Decisions on town planning, active transport and places of play for all can be a part of “a reckoning with the history of control” and lead to “a shared project of living in ways that materialise the redemption of

God”.26

FLOOD

The book of Acts is the account in the Bible of the early church. The sequel to Luke’s Gospel, it describes the collision of cities with Empire, of hospitality with persecution, of intimacy with inclusion and much more. A powerful observation of the book by Jennings is that in it “almost no one is doing what they

want to do.”27 It is the Spirit of God that sets the agenda in a way that is transcendent, transparent, and, crucially, transgressive. Our desires, intentions, and plans are not enough for the extraordinary challenge of overcoming fragmented places and peoples. To paraphrase Solzhenitsyn, the line of separation runs right through every human heart. Our greatest need may be for that which is beyond ourselves.

On the odd occasion, after some heavy rainfall or nearby construction work, the basement in Trinity Church is flooded. It is a reminder that in the Lower Gardiner Street area, the water table remains high. This could be dismissed as a mere incident of geography and engineering but it should be a prompting that we are bound to the soil beneath our feet, to the swamps and ponds that give us life, that came before us and will outlast us all. Maybe then we might remember that we are bound to one another, that in our fragmentation of need and place we are still holding out hope that all will be made new.

Footnotes:

1 “Disused Churches” in The Irish Times, 9th May 1914, p. 6

2 “Trinity Church: Meeting of the Congregation” in Weekly Irish Times, 30th May 1914, p. 15

3 Terry Fagan, a local historian who grew up in the north-east inner-city holds archives which include actual rent books from landlords living in Castleknock for their tenement properties around Gardiner Street. Terry’s walking tours of the area are not to be missed https://www.facebook.com/ montowalkingtours/

4 The Sunday following the editorial’s publication, 261 people attended worship in Trinity Church and a dispute began between the Diocese and many parishioners which would run for five years and require the intervention of the Charitable Commissioners before Trinity Church was closed in 1919. It reopened as a place of worship in 2008, when Trinity Church Network, a coincidentally named independent evangelical church, took over the building following its time as the Labour Exchange.

5 Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010). pp. 24-28.

6 Vine Deloris Jr., God is Red: A Native View of Religion, 30th anniv. ed. (Golden, CO: Fulcrum, 2003), pp. 61-76, 113-32.

7 The Irish Times view on homelessness and Gardiner Street: the inner city takes the burden again. The Irish Times, 3rd December 2023.

8 The NEIC (North-East Inner-City) is both a geographical area and a defined focus for a Department of the Taoiseach led regeneration initiative. For details of this work see www.neic.ie

9 Willie Jennings, Theology and Mission Brady Lecture, Northern Seminary, Illinois, USA, 10th June 2022

10 Fintan O’Toole. A tiny area of Dublin is Ireland’s most segregated district. The Irish Times. 25th July 2023

11 Willie Jennings, Theology and Mission Brady Lecture, Northern Seminary, Illinois, USA, 10th June 2022.

12 Doreen Massey. Geographies of Responsibility in Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, Vol. 86, No. 1, Special Issue: The Political Challenge of Relational Space (2004) pp. 5-18.

13 Philip Sheldrake. The Spiritual City (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell, 2014) p.109.

14 John Rocque’s map of Dublin (1756) is a highly accessible resource for understanding the history of the area. It is most easily viewed through Harvard University https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/scanned-maps/ catalog/44-990114744870203941

15 Some incredible archiving work is taking place to allow access to the many thousands of deeds drafted around the country since the 18th century at the Registry of Deeds Index Project Ireland https://irishdeedsindex.net/ grantors/index.php

16 David Dickson, Dublin – The making of a capital city (London: Profile Books, 2014) p. 257

17 Dublin’s suburban story is, of course, a complex one. The city exhibits both the “old world” scenario of poorer communities living in the outskirts and the ‘new world’ scenario of the wealthy moving out to protected suburbs. That story must include the NEIC itself as it fits well to the understanding of “inner suburb” articulated by Nathan and Unsworth: Max Nathan and Rachael Unsworth. Beyond City Living: remaking the Inner Suburbs in Built Environment Vol 32:3 Summer 2006, pp. 1-20.

18 Willie Jennings, The Bampton Lectures, Lecture 3: Overcoming the Delusion Condition of Home Ownership, University Church Oxford, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uL4dj6Td2hI

19 Stephen Heblich, Alex Trew and Yanos Zylberberg East Side Story: Historical Pollution and Neighbourhood Sorting Spatial Economics Research Centre, LSE, 2017 http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/82544/1/SERC_ Spatial Economics Research Centre_ East Side Story_ Historical Pollution and Neighbourhood Sorting.pdf

20 Blowing in the wind: why do so many cities have poor east ends? The Guardian 12th May 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/12/blowing-wind-cities-poor-east-ends

21 World Health Organisation. What are the WHO Air quality guidelines? https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/what-are-thewho-air-quality-guidelines

22 Environmental Protection Agency, Air Quality in Ireland report 2022. https://www.epa.ie/publications/monitoring–assessment/air/Air_Quality_Report_22_v8v2.pdf

23 Environmental Protection Agency. Nitrogen Dioxide Diffusion Tube Survey in Dublin: 2016-2017 https://www.epa.ie/publications/monitoring-assessment/air/Technical_report_NO2_diffusion_tubes_Dublin.pdf

24 The specific disease outcomes most strongly linked with exposure to air pollution include stroke, ischaemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, pneumonia. Health impacts: Air quality, energy and health, World Health Organisation. 2024. https://www.who.

int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-andhealth

25 Willie Jennings Can “White” People be Saved: Reflections on Missions and Whiteness. Fuller Studio, 2018. https://waww.youtube.com/ watch?v=SRLjWZxL1lE

26 Willie Jennings, The Bampton Lectures, Lecture 4: Addressing the Hateful Condition of the Line, University Church Oxford, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uL4dj6Td2hI

27 Willie Jennings, Acts. Belief: A Theological Commentary on the Bible (Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox, 2017) p. 254