‘Children in Gaza are being shot by snipers’

This is a sentence that should never have to be uttered or written but unfortunately these are the words of Dr Mark Perlmutter, an American doctor who volunteered at a hospital in Gaza in April and May of this year. The children of Gaza are also starving. With agricultural lands destroyed and not enough aid getting into the country, a man made famine is taking place.

At JCFJ we have examined war through an integral ecology lens more than once. In 2021, after an escalation in the Gaza Israel conflict, we examined the interactions between war and environmental care – “The anti-war fight is a climate fight, they are simply different perspectives of the same problem.” With the invasion of Ukraine by Russia we focused on the interconnection of energy and war. In 2023 my colleague Cherise visited Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, she witnessed how the breaking of connection with land, particularly the destruction of olive trees which are an intergenerational labour of love, is used to break a people. In January we reiterated that war is an environmental issue and that “We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both social and environmental.” (LS139)

War and conflict is a time where the interconnection between social and the environmental crises becomes absolutely clear. War is an act of violence not only against the people the bullets and bombs are directed at, but also the homes in which they live, the schools in which they study, the agricultural land in which they grow their food, the water they drink and the air that they breathe. In Laudato Si, Pope Francis calls us to “become painfully aware, to dare to turn what is happening to the world into our own personal suffering and thus to discover what each of us can do about it.” (LS19). Aware of the trauma which orphaned children are experiencing which will stay with them for the rest of their lives. Aware of the terror of losing your children to incessant bombing, hunger and sickness. Aware of the sheer exhaustion Palestinians must feel constantly searching for safety, for food and for shelter.

War and Hunger

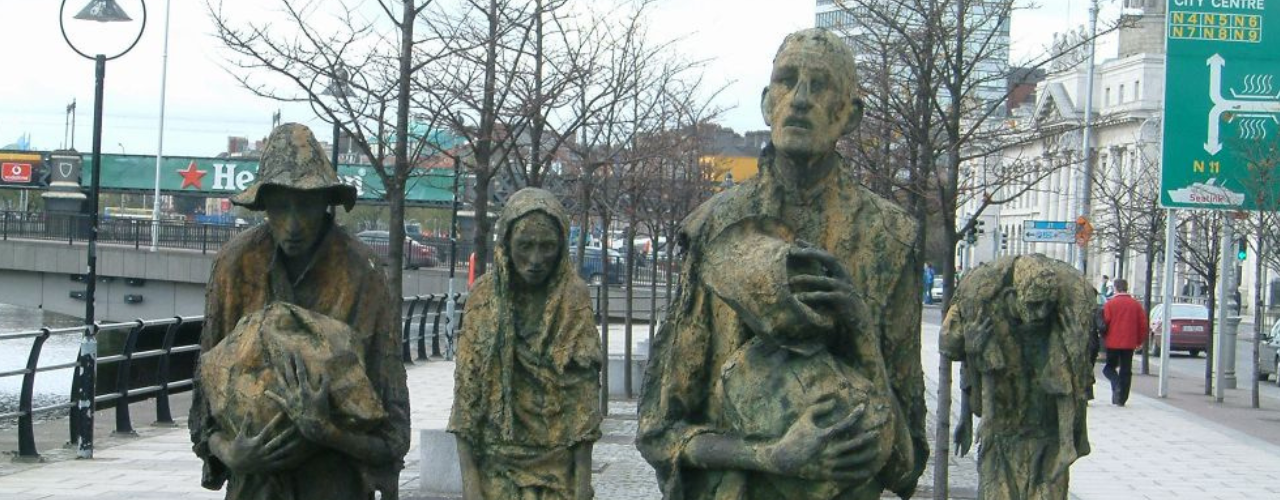

War and famine are intrinsically linked. In a desperate cycle of hunger, conflict can follow hunger and hunger usually follows people who are impacted by war. While the use of starvation as a weapon of war is now deemed a war crime – this was only formalised 1977. Its use has been documented throughout history. Millions died in the Vietnam war as a consequence of several factors including the deliberate destruction of land in Vietnam by the toxin Agent Orange which not only caused the death of forests but also rendered vast areas of agricultural land unusable. Where food was plentiful it was blocked from reaching those who hungered. In WWII the Nazi Hunger Plan starved 42 million Soviets. The Americans also employed this tactic in Operation Starvation against the Japanese in 1945. In the 1970’s, under Pol Pot’s regime of terror in Cambodia nearly 2 million were killed, many from starvation.

Now although recognised internationally as a war crime – hunger is again used. In Ukraine thousands of acres of fields full of grain have been burned or destroyed with hunger becoming increasingly problematic across Ukraine. In what may be the most blatant weaponization of food in recent times is the prevention of food aid crossing borders into Sudan and Gaza. The impact in these regions is devastating. In Sudan the cutting off of aid to starving people, alongside the destruction of large swades of productive agricultural regions, is predicted to cause a famine of proportions which the world would never wish to see again. Gaza is perhaps the most documented of the recent conflict derived famines. In the same account as mentioned above, Dr Mark Perlmutter is clear that it is not only snipers which threaten the children of Gaza but ‘absolutely all’ of the children in Gaza are at risk of starvation. The lines of aid truck lines up at the border highlights that this famine is not an accident, or an unpreventable part of war, but a deliberate outcome of a policy to prevent food and aid reaching those impacted by the bullets, shrapnel and collapsing buildings.

Climate and hunger

Conflict highlights our capability to inflict pain and suffering on each other. It brings the painful question to the fore that if the violence, like the Genocide in Gaza, is allowed to continue how will we join together tackle climate change – the largest global problem which has ever existed. If the suffering of the people in war torn areas is unable to painfully impact us – will those who are impacted most by climate change be able to move us to reduce our emissions for the common good?

In some ways the impacts of climate change mirrors the impacts of war in slow motion. Changes in the water cycle, flooding and drought, can result in previously productive agricultural land becoming barren triggering widespread hunger and food insecurity. Famine is already a consequence of climate change. How widespread this becomes is a result of how much we can reduce our emissions and adapt to the changing climate which makes growing food in some places impossible.

Turning our eyes collectively towards the suffering of others, we need to see what we can do to care for our Common Home and the people within it. Demanding ceasefires and an end to war, demanding stronger climate action, demanding increased aid to move across borders to those who need it are all ways in which we can help. Doing nothing cannot be an option.