Small Things Like These

Like many, I am eagerly anticipating the film adaptation of Small Things Like These. I devoured Claire Keegan’s gripping novella about a Wexford man’s discovery of a Magdelene Laundry in a local convent in a single sitting. With my rapidly dwindling attention span, I appreciated the telling of a deeply incisive story in less than 130 pages. As she explored the social and cultural forces surrounding Bill Furlong’s discovery, Keegan made the bold choice to set the story in 1980s Ireland – a time closer to Ireland’s emergence as a wealthy, modern European country than the economically and culturally protectionist 1950s Ireland. But her bravest choice was to elucidate and tease apart the “bystander effect” which accompanied decades of coercive confinement, institutionalisation, and abuse.

Resigned to the Past

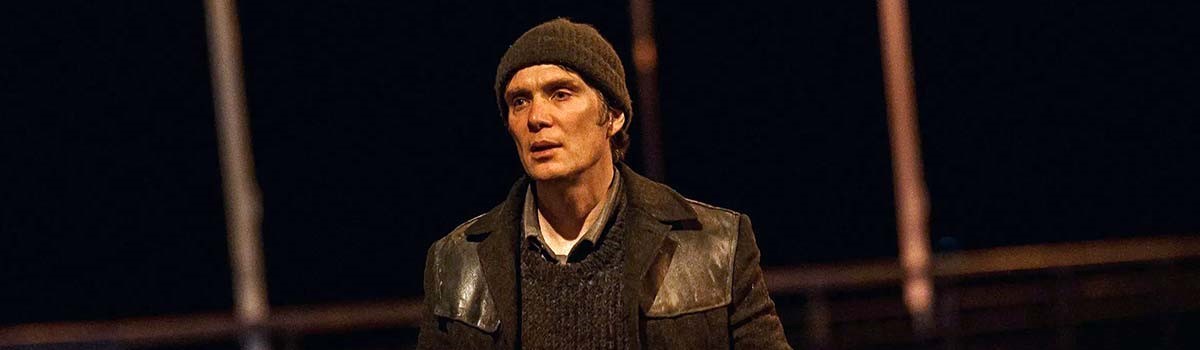

During the week, I caught a little of lead actor Cillian Murphy’s promotional work for the film and there was an unequivocal sense that Keegan’s subject choice was in the rearview mirror, firmly resigned to history. In some ways, this is true. The last Magdelene Laundry shockingly closed on Sean MacDermott Street only in 1996. But, if I am reading Keegan correctly, she does not let us off the hook that easily in Small Things Like These. By vividly bringing to life the “bystander effect” and its attendant social forces, Keegan avoids these binaries of past and present and encourages us to ask whether we would say anything or, instead, turn a blind eye to pervasive institutionalisation in our own time.

Present Institutionalisation

With the 33rd Dáil to be dissolved next week for an election at the end of November, now is an opportune time to observe the trends of institutionalisation over the last four years in the Fine Gael/Fianna Fáil/Green coalition. What follows, by way of numbers, is indicative—as the respective figures are published in different forms by different Departments and agencies—but it points to a modern Ireland which is not yet so distant from its alleged “dark ages” past.

In the four years up to June 2024, we see a clear increase of institutionalisation when we consider homeless people, prisoners, and those in direct provision with leave to remain. These three cohorts alone total almost 25,000 people and at the heart of the rise is this Government’s housing policy. The link to those in homeless institutions is obvious. The Irish Prison Service reported in 2022 that 10% of prisoners enter prison from “no fixed abode” and often leave to the same lack of shelter. People with status in direct provision have to prolong their time in these institutions as they are unable to access private or social housing. When the Government favours the commodification of housing over the provision of affordable, secure homes, institutional settings step into this dereliction of duty.

The number of children in prison in Ireland is negligible compared with the adult population. But when the number of children in homeless accommodation and direct provision are also considered, there are almost 12,000 children in institutions. The Ombudsman for Children has long been critical of the detrimental, long lasting impact that not having a stable living situation can have on children and their development. Such facts ought to be seared into our consciousness. But to what extent are we in fact replicating a kind of strategic ignorance prevalent in previous generations by keenly avoiding certain social realities?

A Lucrative Industry

Bill Furlong’s discovery occurred as he worked for a local business supplying coal to the convent. As he wrestled with his conscience and agency, interlocutors noted that opportunities for his children to attend the adjacent “good school” may be lost if he raised a fuss. Many local businesses were kept afloat and jobs maintained in Ireland during various recessions as they supplied goods to the Laundries. Yet, recent research has demonstrated that the flow of goods and services went both ways. The system benefitted some of the most elite and privileged corners of Ireland.

Customers of the Donnybrook Magdelene Laundry included: Blackrock College, the National Maternity Hospital, St Vincent’s Hospital, the Mater Private, University College Dublin, RTÉ, Captain America’s, Elm Park Golf Club, Fitzwilliam Lawn Tennis Club and the embassies of Canada, France, Japan, and Argentina. Even laundry from Áras an Uachtaráin was sent there to be cleaned. A cross section of Dublin’s social elite availed of, and benefitted from, the reasonable fees on offer due to the institutionalisation and unpaid labour of the abandoned women.

What is clear with the rising institutionalisation in contemporary Ireland is that, again, a select few are making very lucrative returns from warehousing people. In 2023, more than 30 private companies were paid more than €10 million to accommodate refugees and asylum seekers. The highest paid company, which operates the Citywest hotel, received more than €67 million, while the next highest payment was €36 million. Several international hotel groups are included on the list of vendors. For private actors in the Government-created homelessness market, the returns are no less lucrative. After an eight-year battle under Freedom of Information, Dublin City Council revealed recently that one company received €7 million over an 18-month period in 2016. Previously, no details of providers were provided, citing business sensitivity adding to the opaqueness.

The risk of creating a binary of the past and present with Ireland’s institutionalisation is to blind ourselves to the present. There is still moralising and intentional State abandonment. By apportioning all the blame to the past, we may inadvertently, and unintentionally, absolve the present.