Earlier this week, the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice published a piece highlighting the recent and deeply concerning spike in pedestrian and cyclist deaths on Irish roads, particularly among children. The article drew on publicly available RSA data to show that progress in protecting vulnerable road users, which had been made in the years prior to the pandemic, has been reversed.

Predictably, the article provoked some defensive responses – including the claim that it was ‘abusing numbers’ or cherry-picking extreme years to make its point. But this kind of reaction is all too common when car dominance is questioned. It reflects not a careful concern for truth, but a discomfort with the implications of what the data shows. Rather than engage the statistics or the underlying ethical argument, there is a tendency to dismiss or discredit, in order to preserve the status quo.

The data in question are official figures, which, if anything – as discussed in the piece – understate the problem. They show a clear trend: fatalities among vulnerable road users declined between 2016 and 2019, before climbing again and peaking in 2023 at the highest level in over a decade. That is not an anomaly. That is a reversal.

The broader picture of road traffic safety in Ireland reinforces this point. Between 2013 and 2019, overall road deaths were on a steady decline. But in recent years, this trend has reversed. According to the Road Safety Authority (RSA), 2023 saw 188 deaths on Irish roads – an increase of nearly 30% on the previous year and the highest total since 2014. Vulnerable road users, particularly pedestrians and cyclists, accounted for a disproportionate number of these fatalities. Pedestrian deaths rose from 27 in 2022 to 44 in 2023; cyclist deaths also increased.

Of course, any assessment of recent trends must take the pandemic into account. Road usage dropped significantly in 2020 and 2021 due to lockdowns and public health restrictions. This inevitably led to a temporary drop in collisions and fatalities. But this only makes the current reversal more troubling. As traffic volumes have returned to pre-pandemic levels, so too have the dangers – amplified, it seems, by a loss of focus on enforcement, planning, and public safety. We cannot interpret the rise in 2023 as a simple return to baseline; it is a spike, not a reset.

This is not just a blip. It’s a systemic failure, and the consequences are clearest when we focus on children. Over the past decade, two-thirds of children killed on Irish roads were either walking or cycling. These are not high-speed collisions on motorways or late-night incidents involving alcohol. These are children walking to school or cycling in their neighbourhoods – engaging in activities that should be ordinary, safe, and encouraged.

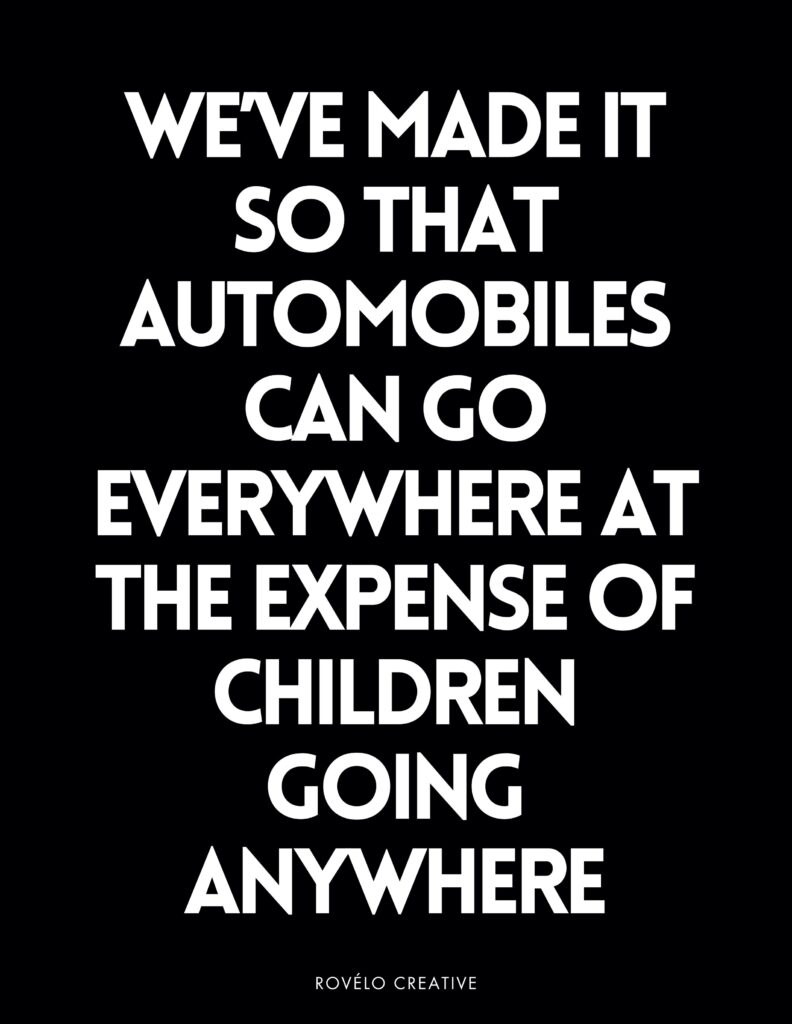

Instead, what we are witnessing is a form of societal resignation. We tolerate a level of road danger that curtails the freedom of children to move through their communities. This is a moral issue. When we fail to police motor offences, when we design streets around the convenience of cars rather than the safety of people, we make a clear choice: to prioritise speed and flow over life and freedom.

Moreover, this culture of tolerance towards danger actively undermines efforts to promote active transport. As climate targets demand a shift from private car use to walking, cycling, and public transport, people will only make that shift if they believe their journeys will be safe. Every cyclist death, every pedestrian fatality, chips away at public confidence in that transition.

The active transport policy advocacy of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice is not based on some wonkish determination that shifting people’s transport modes to busses will bring about utopia. It is rooted in lived experience – particularly the voices of children in Dublin’s North-East Inner City. When invited to talk about their neighbourhood, they speak, again and again, about the fear they feel walking to school, playing near roads, or even waiting at pedestrian crossings. They describe terrifying moments when a car breaks a red light, speeds through a junction, or mounts a footpath. These are not just near-misses. They are daily reminders that the places meant to be theirs are instead governed for machines.

Each of these moments is a crime under the statute books – but ask the children, and they know the truth: these are crimes that will never be policed. They know their lives are not the priority.

This is what gives urgency to the statistics. The data is not presented as a standalone technical argument. It helps us see the shape of a public safety failure whose consequences fall disproportionately on children, particularly when they are engaged in activities integral to childhood: walking, running, riding bikes.

The article makes a historically and ethically significant point: progress was possible, and we have let it slip. Yet any effort to critique motor-normativity – to suggest that the status quo of car dominance endangers lives and limits freedoms – often encounters reflexive pushback. The accusation of “abusing numbers” reflects this broader defensiveness. Rather than engage the evidence or the ethics, critics too often deflect, protect the primacy of cars, and dismiss those who call for change. But pointing out that our streets are unsafe for children is not an attack on drivers; it is a demand for justice.

What is needed is not a choice between statistical rigour and ethical seriousness, but a recognition that the two reinforce one another. Too often, those who seek to delay or dilute the shift to active transport question the use of statistics not to clarify the picture, but to cast doubt on the need for urgent change. They misread data as though year-on-year comparisons imply causality, and they over-read it by insisting that moral arguments should be made without reference to empirical trends. But data is not only for analysts – it is a tool for citizens, campaigners, and communities to grasp the shape of the world they live in, and to act when it is found wanting. When children are being killed on our streets, interpreting that data carefully and acting on its moral implications are both necessary. In moments like these, statistical clarity and ethical urgency belong together.