Imagine if we introduced an annual award ceremony for Ireland’s most successful criminals. Who might be present at such a gala event and who would be likely to receive nominations and awards?

It is unlikely that such an event will ever happen but the very suggestion might help us think about some of the problems with our contemporary images and assumptions about crime, anti-social behaviour and fairness in Irish society.

Problem people and problem Places

When we think of crime and punishment we think of certain places, certain individuals or groups, certain behaviours and lifestyles that are a ‘problem’. We have problem places or ‘problem people’, and problem activities that provoke our outrage and indignation. We demand tougher action and we express alarm at the rise in crime and lawlessness. But it is a particular type of crime that evokes such as a reaction. As the Report of the National Crime Forum observed, the public perception is that crime is burglary, car theft, violence and other similar activities committed largely by young people from deprived areas and often related to illegal drug use.

Such a common perception fails to take account that the most ‘successful’ criminals in terms of both the relative rewards of their wrongdoing and their ability to escape detection and punishment are not the poor but the rich and relatively rich.

There is a group of diverse activities that the rich and relatively rich engage in, such as fraud, tax evasion, drink driving, breach of laws governing commercial activity and the deliberate neglect of safety standards that receives little attention and is rarely and reluctantly regarded as a serious social problem requiring urgent action.

Harm Done

This cannot be justified on the basis that the offences are not serious or cause insignificant harm. Some of these activities result in major financial loss, death and serious injury and can pose serious risks to the safety and lives of large numbers of the public. In 2005 a total of 38 cases of dangerous driving resulting in death were recorded which is only 16 fewer deaths than those resulting from homicide. We also know that the cost of tax evasion, corporate crimes and insider trading, is estimated at many times greater than the value of property stolen in thefts and burglaries. For example the value of property stolen in burglaries, robberies and thefts in 2004 and 2005 was close to 80 million euros in each year whereas cases involving Ansbacher type arrangements (just one of many special investigations) have to date resulted in recovered payments in excess of 60 million euros.

| TAX EVASION CASES | ||

| Investigation | No of Cases | Payments to Revenue (in million euros) |

| Dirt | 12,212 | 842 |

| NIB | 465 | 57 |

| Ansbacher | 289 | 62 |

| Mahon Tribunal | 27 | 30 |

| Offshore Assets | 13,990 | 826 |

| BURLARIES, ROBBERIES and THEFTS | ||

| Value of Property Stolen in 2004 | 78 | |

| Value of Property Stolen in 2005 | 78 |

Table 1. Size of payments made to date arising from some Special Revenue Investigations into tax evasion and the value of property stolen in burglaries and robberies.

Of course financial cost is but one indicator of harm caused in robbery and burglary and any consideration of the harm done must include the effect on a victim’s sense of safety and security. Though difficult to measure, such harm can be immense especially when the victim is elderly or otherwise vulnerable. Yet, without minimizing the reality of such harm, it also needs to be highlighted that tax evasion and other ‘white collar crimes’ are not victimless crimes. They also have social and personal consequences. These consequences may be equally difficult to quantify but for example it is clear that tax evasion undermines social solidarity and also denies the state resources that could be applied to necessary public services.

Financial wrongdoing on the part of the rich rarely evokes the response of the criminal justice system. Often these incidents of wrongdoing (if detected) are more likely to be dealt with by way of financial penalties enforced by bodies outside of the criminal justice system. As the following newspaper report highlights such sanctions are rarely accompanied by moral censure by peers: “The fact that the Republic\’s biggest bank got a public rap on the knuckles from the Irish Financial Services Regulatory Authority (IFSRA) for “deliberately hiding” the fact that it had overcharged thousands of customers more than €30 million for almost eight years has barely registered a ripple within the investment community,”

Language Tricks

Perhaps because the most significant feature of this form of wrongdoing and criminality is that it is often dressed up in a manner to convince us that this activity is not really a crime or wrong. It is notable that he word ‘crime’ is rarely associated with tax evasion. Rather it is talked about in terms of its polar opposite – compliance with the law. Similarly a young person who takes from a shop without paying is labeled a ‘thief’ but a similar label is rarely applied to the person who collects VAT from customers and does not pass it on to the revenue. Such a person is more likely to be referred to as a ‘hard-pressed entrepreneur’ or such like. Through such language games, illegality on the part of the relatively rich is transformed into a mere failure to comply with regulations. However the same language tricks are not available to dress up the crimes of the poor.

Even if cultural attitudes tend to be resistant to associating crime with the rich and relatively rich, we have become more aware of the scale of their wrongdoing. Considerable media attention in recent years has focused on tax evasion by banks and their customers, payments to politicians and corruption in the planning process. As a result there has been an increase in awareness and concern about such activities but it appears as if an attitude of ambivalence still prevails. This is in stark contrast with the attitude of intolerance that dominates when crimes of the poor and vulnerable are considered.

The Rich Get Richer And The Poor Get Prison

The difference in attitude translates into very different strategies and different outcomes when it comes to dealing with the wrongdoing of rich and the wrong doing of the poor. As G.B. Shaw colourfully put it:

The thief who is in prison is not necessarily more dishonest than his fellows at large, but mostly only one who through ignorance or stupidity steals in a way that is not customary. He snatches a loaf from the baker’s counter and is promptly run into jail. Another man snatches bread from the tables of 100 widows and orphans and simple credulous souls, who do not know the ways of company promoters and likely as not he is run into parliament. (Shaw: The Crime of Imprisonment 1922)

Tax Crime and Welfare Crime

In the Ireland of today the disparity that Shaw highlights is most evident in the different attitudes and responses to tax evasion and welfare fraud. Significant differences exist in the public perception of various ‘scenarios’ involving tax evasion and welfare fraud. Perhaps few people now boast about tax evasion and attitudes may be evolving, but annual figures show that tax evasion is pervasive. Over 30,000 cases of tax crimes have been uncovered and settled in recent years through the special investigation projects (DIRT, Ansbacher, Offshore Assets etc.) The amount collected in this process exceeds 2.2 billion euros.

Although tax evasion has been a criminal offence since 1945 few prosecutions have been taken and up to1997 not one person was send to prison for tax evasion.

| Year | 1945-1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 |

| Number | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 2. Numbers Sent to Prison for Tax Crimes by Year

Source: Annual Reports of Comptroller and Auditor General and Seanad Eireann (Vol 181) Deabte, 5 October 2005.

In 2005 a total of 30 cases were considered for prosecution for serious tax evasion. 12 convictions were obtained in court, which resulted in two sentences of 3 months imprisonment being imposed on a director of an oil distribution company. Four other custodial sentences handed down to a farmer, a disc jockey, a contract cleaner and a sales administrator were suspended.

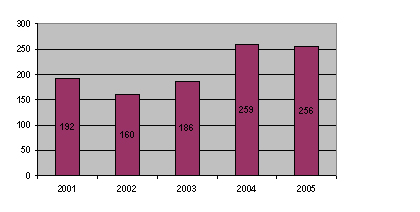

In contrast in 2005 a total of 256 people were prosecuted for Social Welfare fraud. Of these 28 were sentenced to terms of imprisonment with 24 of these sentences suspended but 4 people were actually sent to prison. (the year before 10 people were sent to prison for welfare fraud. 122 were fined or received community service.

Table 3: The number of prosecutions for social welfare fraud finalized

in the courts since 2001.

A test: Is punishment economic to pursue and is it productive?

It would be misleading to suggest that the Revenue Commissioners are indifferent to tax evasion, in fact recent years have seen increased efforts to clamp down on this type of crime. What is significant in the treatment of welfare fraudsters and tax fraudsters is the mentality behind the approach adopted. In dealing with tax collection, priority is given to ‘pursuing’ but not necessarily to prosecuting tax offenders. A central argument used in the non-prosecution of tax evaders is economic logic. As the Minister for Finance recently stated: ‘a practical approach must be adopted to avoid Revenue resources being tied up in what is an extremely labour intensive process and where the outcome may ultimately be un-productive.’

In other words where the cost of recovery of taxed owed is not proportionate to the return, arrangements are made to write off the tax. In 2005, €19m euros owed in over 60,000 cases was written of for these reasons.

An extension of this economic logic applies to the type of ‘punishment ‘ handed out for tax crimes. The majority of cases where evasion is discovered are concluded on the basis of a negotiated settlement with the tax offender. This involves the collection of the unpaid tax along with interest and heavy penalties. In addition a list of tax offenders (defaulters) usually running to 200 names is published each quarter. The approach is neatly summarised by Senator Mansergh who stated: ‘It costs 80,000 euros to keep a person in prison for a year. Frankly that is not a good use of the State’s money. It is far preferable to recover the money with interest and penalties and to name and shame.’

Perhaps this is a pragmatic approach but the same economic logic does not seem to apply to the prosecution of welfare fraud or to other forms of theft. Of the 143 million euros of tax written off in 2005, €3.9m was automatically written off in cases with balances less than €500. If thefts (as commonly understood) involving property of a similar value were written off, then close to 90% of reported thefts would go un-prosecuted. Would the public accept it if the Gardaí declared openly a policy not to prosecute shop-lifters or burglars because it was clear that the goods or the value of the goods could not be recovered or that the person was destitute? I think not! Would there be much public support for a policy that proceeded with welfare fraud cases only on the basis that the prosecution costs were less than the average (€5,000) defrauded?

A similar point applies in regard to punishment. We may ask if it good use of the State’s money to send a homeless alcoholic or drug addict to prison where he will receive little or no support to address his addiction and is therefore more likely to re-offend. If such outcome analysis as applied in the punishment of tax offenders were applied equally to the crimes of the poor then we might see a radical and welcome move away from the use imprisonment and the increased use of alternative and more effective sanctions.

Fear of Serious loss, Injury and Death.

Concern about crime is often linked to people’s fear for their personal safety and their property.

Even greater concern is generated by crime involving violence resulting in serious injury or death. For many the threat to ‘life and limb’ and public safety, posed by this sort of crime necessitates imprisonment. There is little evidence of a similar fear or moral panic arising from other forms of law breaking that can equally pose serious risk of personal injury and death. Despite the well-known risks involved in drink driving, last year over 13,000 cases of drink driving were detected. Yet there seems to be little demand for the use of imprisonment against this sort of behaviour.

One writer has put it well when she wrote:

The public tend to be far more afraid of being mugged, or robbed by a stranger on the street that they are of being killed on a commuter train, poisoned at a wedding or seduced by a host of misleading advertisements, cheap bargain offers or bogus investment schemes.

It is amazing to think that each year more people die in their work-place than are murdered. According to the Health and Safety Authority, in 2005 a total of 73 people died in work related incidents, an increase of 25% on the number for 2004. In 2005 there were nineteen so-called gangland murders. It is estimated that there are over 50,000 people seriously injured at work each year and in excess of 40,000 people who get sick due to work related activity. In addition to the human suffering arising from these incidents a recent report commissioned by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment estimated that the financial cost of work-related accidents and ill-health could be as much as €3.6 billion, which is equivalent to just over 2.5% of national income for Ireland!

Of course it is understandable that we might be more tolerant of harm that comes about accidentally than harm that is deliberately inflicted. And while it is unlikely that 100% adherence to all Health and Safety laws by employers would eliminate work-related accidents and deaths, experts do claim that higher levels of compliance with safety laws the harm done. Yet, public concern about the deliberate neglect of these health and safety laws fades into insignificance when compared to the fear and moral panic generated by gangland murders. Review of the 2005 annual report of the Health and Safety Authority shows that of workplaces inspected, aspects of the law was not being adhered to in up to 40% of cases.

It is not that the State is indifferent to the harm caused by work-related incidents nor is it formally colluding with the criminal failures of employers in so far as they do not behave according to the obligations placed upon the, by the law. However enforcement of these laws is undertaken in the first instance by a body that acts outside the criminal justice system. This body adopts a particular approach that seeks to educate and support employers adhere to the law. The approach is characterised by collaboration between the law enforcement body and the potential offenders who are assisted and encouraged to comply with the law. A key aspect of the work of the HSA is to get people to ‘buy into ‘ the requirements of health and safety law. It is therefore not surprising that prosecutions under the Health and Safety Act are rare and the most severe punishments imposed are fines. In 2004, 40 prosecutions were taken by the HSA, resulting in fines totalling €463,338 .No one was imprisoned for breaking health and safety laws. Yet we know that homeless and vulnerable people are prosecuted for relatively minor offences and routinely punished with imprisonment.

Targeting Vulnerability

Prisoners and those who come before our criminal courts are not drawn randomly from across the country or drawn randomly from across the social classes. A detailed examination of the addresses of all people sent to prison in 2003 concluded that the Irish prisoner population “ is disproportionately drawn from those districts which combine high economic deprivation scores with high population density.” Dublin accounted for nearly half of individuals committed to prison, though only 31% would be expected for its population.

Of the 9,000 people who are sent to Irish prisons each year, most are poor and the vulnerable in society. Most prisoners have poor education, housing problems, little job experience, and most have drink, drugs and mental health problems. Ninety percent of the people sent to prison are male and the most are under forty and over 15% under twenty-one years of age. A study published last year noted that one in four inmates in Irish prisons were homeless when sent to prison and more that 80 per cent of them were using heroin and/or cocaine on committal. Of the 25 per cent who were homeless on committal one in three had been previously diagnosed with a mental illness and two in three had spent time in a psychiatric hospital. Over half were unemployed at the time of committal.

This snap shot confirms the perception that it is the sad, and the mad as much as the bad who end up in prison. In other words disadvantaged and vulnerable offenders make up a significant proportion of the prison population. Contrary to popular stereotypes it would also appear as if many are in prison for non-serious offences. For instance 85% of all committals to prison in 2005 were for non-violent offences.

Experience of the criminal justice system (the Garda Síochána, the Criminal Courts, the Probation Service and the Prison Service) varies considerable for a rage of groups- the advantaged and the disadvantaged; the successful and the vulnerable; old and young; men and women, Irish citizens and non-nationals. Beliefs that the criminal justice system is impartial run into trouble particularly when we look at who gets sent to prison.If we look at the characteristics of those in prison in the context of the population of offenders it hard not to conclude that the rich get richer and the poor get prison!

National Crime Forum Report, IPA, 1998, p109.

An Garda Siochana Annual Report 2005, p 24

ibid, p 44

Comptroller and Auditor General Annual Report 2005, p 16.

Irish Times 10 Dec 2004.

Source: Annual Reports of Comptroller and Auditor General and Seanad Eireann (Vol 181) Deabte, 5 October 2005.

The figures relating to tax evasion and welfare fraud are taken from Report of Comptroller and Auditor General 2005, p11 and p 134.

Report of Comptroller and Auditor General 2005, p 141

Seanad Eireann (Vol 181) Deabte, 5 October 2005.

ibid, p 11.

Seanad Eireann (Vol 181) Deabte, 5 October 2005

H Croall, White Collar Crime, Buckingham: Open University Press, 1992 p3.

NCAOP (2001), HeSSOP, Report No. 64, p. 186.

Seymour, M. and Costello, L, A Study of the Number, Profile and Progression Routes of Homeless Persons before the Court and in Custody in Dublin. Probation and Welfare Service/Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Dublin 2005

This pattern does not necessarily hold when we look at the most serious of offences such as murder and sexual offences but prisoners convicted for these offences are a minority of the prison population.

Harry Kennedy et al Mental Illness in Irish Prisoners:Psychiatric Morbidity in Sentenced,

Remanded and Newly Committed Prisoners, Dublin: National Forensic Mental Health Service. 2006, p57.

Rural poverty does not carry with it the increased risk of imprisonment that is conveyed by urban poverty. Travellers are also over-represented in the prison population when compared to the proportion of Travellers in the total Irish population. In one study travellers accounted for 5.4% of the prison population whereas they represent less than 1% of the entire population.

Seymour, M. and Costello, L, A Study of the Number, Profile and Progression Routes of Homeless Persons before the Court and in Custody in Dublin. Probation and Welfare Service/Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform, Dublin 2005

Irish Prison Service Report 2005, p13.

My thanks to CFJ staff who read a draft of this article and made some useful comments.

Article by Tony O’Riordan SJ