Introduction

What might good prison policy look like in practice? In an article in The Guardian in May 2012, Halden Prison in Norway, which opened in 2010, was described as ‘the most humane prison in the world’.1 Yet the prison is, in fact, a high-security jail accommodating about 250 prisoners found guilty of the most serious offences, including murder, manslaughter, and sex offences.

Eoin Carroll

The environment and regime of Halden are designed to be as ‘normal’ as possible – to be, in effect, as ‘unprison-like’ as is possible. People detained in Halden have rooms with cupboards and desks but without bars on the windows; they have access to their own toilet and shower.

The prison’s normalisation agenda is expressed not only in its physical environment but in its regime. Lock-up times are much shorter than those experienced by the great majority of people in prison in Ireland – eleven hours, as compared to around seventeen hours. The daily routine involves cells being unlocked in the morning and not locked again until the evening. Prisoners are provided with opportunities for work and education and are encouraged to avail of these. Meals are taken in communal areas and there are also facilities for prisoners to cook their own meals. In the Guardian article, the Governor of Halden is quoted as saying: ‘The life behind the walls should be as much like life outside the walls as possible.’2

Irish Prison Policy

Within the Irish context, the Mission and Values of the Irish Prison Service express a commitment to ‘apply appropriately the principles of normalisation’. However, the caveat implicit in the phrase ‘apply appropriately’ ought to be unnecessary: normalisation should refer to what is considered the norm in society and so, with a rise in living standards and expectations in the general community, there should be a corresponding improvement within the prison system. This, however, has not been the case in Ireland.

Writing in The Irish Times in June 2012, Ian O’Donnell, Professor of Criminology, UCD Institute of Criminology, suggests there is a ‘deep reservoir of public and political apathy’ regarding what happens in our prisons.3 He highlighted the fact that a commission set up in May 2007 to investigate the violent death in prison of Gary Douch had yet to report on its findings.

He noted too that the Prisons Hygiene Policy Group, established in 1993 and charged with evaluating hygiene standards in prisons, had in its final report in 1997 recommended that an existing commitment to provide in-cell sanitation in all prisons by 1999 should be revised so as to bring forward the deadline, and that in the meantime 24-hour access to toilet areas should be provided. In the event, however, even the 1999 deadline was not met. The most recent commitment, contained in the Irish Prison Service’s Three Year Strategic Plan 2012–2015, is that in-cell sanitation will be provided in all prisons by 2016 – seventeen years after the 1999 deadline.4

The years of economic boom and Exchequer surpluses provided an opportunity to make radical improvements across the Irish prison system. However, while there was significant provision of new prison places, the overall approach could be described as one which assumed that ‘bigger is better’. A number of smaller prisons were closed and there was a move towards creating prisons of scale. Prison building plans tended to take it as given that new provision would mean more provision. The Department of Justice policy document, The Management of Offenders: A Five Year Plan (1994), and several Department of Justice strategy documents throughout the 1990s and 2000s, envisaged improved conditions being accompanied by additional prison places.

The justification for penal expansion of this kind was the perceived need to ‘future-proof’ prison provision for the next fifty years. The proposed Thornton Hall project, in north Co. Dublin, was put forward as a response to the serious problems existing in Mountjoy Prison: poor physical conditions, overcrowding, violence, and lack of sufficient access to constructive activities. But, tellingly, the design capacity for Thornton Hall was for 2,200 people – more than double the number of people detained in the Mountjoy complex.

Several advocates and interest groups repeatedly voiced concerns about the proposed development5 but it was the crisis in the public finances which prevented the project going ahead – at least in the short to medium term.

That is some of the bad news, but, where have been the success stories in prison building programmes in Ireland? Has there been a ‘Halden moment’ in Irish penal policy? And if so, how did it become a reality?

The Dóchas Centre for women prisoners, which is located in the Mountjoy Prison complex, was widely acknowledged in the years immediately following its opening as being a model facility. It replaced the seriously inadequate women’s prison that had existed at Mountjoy up to then. However, Dóchas was opened only after more than twenty years of repeated calls for improved conditions for women in prison. How did it come into being? A study by the author of the decision-making process that led to the establishment of the Centre provides some interesting insights.6 This study was carried out in 2011, and involved interviews with key actors in the lengthy, and far from straightforward, process that eventually led to the opening of the Dóchas Centre in 1999.

Understanding the Policy Process

Many commentators have highlighted that there is a dearth in research into, and understanding of, the policy process.7 For example, Trevor Jones and Tim Newburn have noted that studies tend to focus on the substance and outcome of policy decisions, rather than how policy is made.8 And Paul Rock has suggested that a policy decision can often be presented as if coming out of thin air, when, in reality, it is more likely that it has emerged from a prolonged process.9

In an attempt to ‘put order’ on the policy process, James Anderson uses a linear representation, with policy creation following a neat and specific course. He views the development of policy as occurring in the following stages: (i) problem identification; (ii) formulation of policy options; (iii) adoption; (iv) implementation; (v) evaluation.10 Others commentators, however, see this as an over-simplification and not a true reflection of what they argue is an inherently messy process.

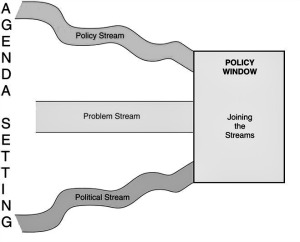

Jones and Newburn suggest that rather than attempting to present the process along artificial linear stages, it is helpful to use the idea of ‘streams’ within the process – an idea proposed by John Kingdon – as a way of examining criminal justice policy.11

In one stream, the problem is identified and defined, possibly even ‘generated’, and seen as requiring attention by policy-makers. Kingdon suggests that problems are likely to be identified by policy-makers or government officials as a result of:

a) indicators – assessment tools, data collection (for instance, in the case of public health, the number of people dying as a result of smoking);

b) crises or disasters, such as train crashes; and

c) feedback – for example, reviews of current programmes.12

In the second stream – the policy solutions stream – a diversity of ideas often float around in what Kingdon describes as ‘the policy primeval soup’. These ideas are generated between actors within policy communities or by individuals who share a common concern in a single policy area. Ideas bounce off one another, alternatives are generated, and combinations formed. Ideas are more likely to be translated into policy if based on technical feasibility and value acceptance.

The third stream is where an opportunity for action presents itself. This is the political stream and it refers to changes in national mood, administrative or legislative turnover, or a successful interest group campaign. In such circumstances, potential agenda items that are in harmony with the national mood and enjoy interest group support are more likely to receive attention.

When the three streams join, an opportunity arises to push an agenda through what Kingdon refers to as a ‘policy window’. Such windows are opened either by the appearance of a compelling problem (or problems) or by an event (or events) in the political stream. Crucial to the process are policy entrepreneurs who act as a glue and who are ‘willing to invest their resources in pushing their pet proposals or problems’.13 Policy entrepreneurs are skilled individuals who await the opening of a policy window so that they can couple their solutions to problems. The image below depicts the relationship between the streams.

Improving Conditions for Women in Prison in Ireland

The Problem Stream

Kingdon’s model is a useful tool in understanding how the Dóchas Centre came into being. The problems relating to the conditions and regime existing in the ‘old’ women’s prison in Mountjoy were documented in several reports in the 1980s: The Report of the Commission of Enquiry into the Irish Penal System, published in 1980;14 The Irish Prison System, a report by the Council for Social Welfare (A Committee of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference), published in 1983, and the Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Irish Prison System (The Whitaker Report) published in1985. The unacceptability of conditions for women in prison was also referred to in the Report of the Second Commission on the Status of Women, issued in 1993.

Ethnographic studies by Barbara Mason and Christina Quinlan highlight the appalling conditions for women in Mountjoy pre-1999.15 In his book, The Governor, John Lonergan describes the women’s prison, which was located in the basement and lower floors of St Patrick’s Institution (the detention centre for young men), as follows: ‘[there was] no integral sanitation, and no washing facilities in the cells. Worse still was the fact that the women were often four to five to a cell’.16 In addition, the only outdoor space available for women in Mounjoy was in an area overlooked by the section of St Patrick’s occupied by young men, who continually shouted verbal abuse at the women and prison staff. The grossly overcrowded conditions, and the multiple occupancy of cells, meant that women were vulnerable to being coerced into using drugs, or becoming involved in unwanted sexual relationships.17

The attention paid to the conditions in the women’s prison throughout the 1980s resulted in only limited, incremental, steps towards improvement. One factor in this was that women constituted such a small minority within the prison population that the conditions in which they were detained did not rate highly among concerns about the system.18

However, in 1990, the death by suicide of Sharon Gregg, the first woman in living memory to die in an Irish prison by suicide, was what might be seen in Kingdon’s terms as a ‘focusing event’ or crisis, which pushed the issue of the conditions in which women were detained higher on the agenda of policy-makers, including politicians.

The Policy Stream

As already noted, Kingdon’s multiple stream framework assumes that policy solutions float around in what he calls ‘the policy primeval soup’. Within what might be termed ‘the prison policy solution soup’, numerous ideas concerning improving conditions for women detained in the Mountjoy complex bounced off each other.

As Kingdon points out, crucial to the success of a policy solution are its technical feasibility and value acceptance.19 Various locations for a new women’s prison were proposed but then fell off the agenda: there were proposals to build a ‘miniature Mountjoy’ in Kilbarrack;20 a unit in the grounds of the Central Mental Hospital; an open prison at Beladd House in Portlaoise;21 and a 150-cell prison in Wheatfield.

In Kilbarrack, however, there was very strong local resistance, resulting in political representations to the Minister for Justice of the time.22 The Department of Health resisted the proposal to build a prison at the Central Mental Hospital. The site at Wheatfield was eventually deemed to be required for the male prison population.23 In the case of the proposal for an open prison at Beladd House, there were concerns regarding the architecture of the building and the perceived risk that women detained there might abscond. Overall, then, these proposed solutions had critical shortcomings regarding location and lack of technical feasibility.

By the early 1990s, it was being proposed that the most feasible option was to simply refurbish the old prison. However, this was a ‘solution’ that was strongly criticised by prisoner advocates24 and by many of those working in the prison.

The Political Stream

As already noted, the ‘political stream’ within the model proposed by Kingdon refers to changes in national mood, turnover in the administrative or legislative spheres, and the impact of interest group campaigns. Immediately after the tragic death of Sharon Gregg in 1990, and in the context of the ensuing public concern and media attention, the Minister for Justice, Ray Burke TD, reiterated his commitment to the refurbishment of the women’s prison, but indicated that this was a short-term solution, thus leaving open the possibility that a new prison for women might be built at some stage.

The Dóchas Center © Derek Speirs

Ms Gregg’s death also generated increasingly vocal concern on the part of opposition politicians. For example, in the Dáil on 7 March 1990 Nuala Fennell TD declared that: ‘I certainly intend to make the Minister’s political life intolerable until the position of women in prison is dramatically improved.’25 Newspapers continued to highlight the plight of women in prison – for instance, an article in The Irish Times by Padraig O’Morain carried the headline: ‘Woman’s death renews demand for prison reform’.26

However, in June 1990, the Minister for Justice, speaking at the Prison Officers’ Association Annual Conference, indicated that the building of a new prison for women was not feasible and that the best solution was refurbishment of the existing unit for 30 to 50 inmates.27 In September 1991, the women were moved into a wing of St Patrick’s Institution which had been refurbished with the intention of being used for juvenile detainees. In mid-1993, the women were again moved, this time into the refurbished B Wing, a location which had previously been used as part of the women’s prison.

Change in the Political Stream

The appointment of Máire Geoghegan-Quinn TD as Minister for Justice in January 1993 was to prove critical to the decision to build a new prison for women at Mountjoy.

Like the previous Minister, Ray Burke, Máire Geoghegan-Quinn TD was a member of Fianna Fáil, which had entered a coalition government with the Labour Party, following the General Election of November 1992. However, she was prepared to take a course which was radically different from that proposed by her predecessor.

She was described by people who were involved at the time as being ‘appalled’ by the conditions in the women’s prison28 which she had ‘inherited’.29 She was also described as having ‘the guts to stand up and say, yes, it can be done’,30 and as being ‘… very clear … she wanted a proper modern women’s prison built.’31 Her relationship with senior civil servants and prison management was also considered to be very positive. There was, therefore, at this stage a clear political commitment to a new prison. Of considerable importance was the fact that there was support for the project by senior civil servants, a number of whom had been appointed at the same time as the new Minister.

Another important feature of the political stream at that time was the involvement of ‘outsiders’ in the planning process for the new prison, with the inclusion of public affairs activists as members of a newly-formed Ministerial Steering Committee/Advisory Group. These members were viewed as being ready to come down on the side of progress,32 as well as giving the civil servants involved a ‘bit of a safeguard’, when it came to controversial issues.

The involvement of ‘civilians’33 was unusual at the time, particularly in the Department of Justice – and was considered by some to be unnecessary.34 Paul Rock, however, suggests that ‘outsiders’ can have an important role in enhancing the legitimacy of the process of policy change and in creating ‘buy-in’.35

Change in the Policy Stream

New to the policy stream was a prison staff in-house discussion group, many of whose members had been working on possible solutions to the accommodation needs of women in prison. The group met formally in January, February and March 1993, and from its meetings a blueprint document emerged in April 1993 entitled, Women’s Prison in Mountjoy: An assessment of needs and recommended regime strategy for positive sentence management. This document provided a vision and practical guide for a new prison and in the view of one respondent, ‘the philosophy of the document was a keystone to the realisation of the Dóchas Centre’.36

This in-house group, comprising key personnel within the prison service, might be understood as constituting what Paul Rock refers to as ‘sub-government’, where policies emerge from the bottom up, ‘advancing from officials to ministers’, and ‘begin by acquiring their identity in the aspirations, imaginations, relations, and activities of perhaps three or four individuals’.37 The ideas and plans of such a group are, however, unlikely to have any impact in the absence of a policy entrepreneur (or entrepreneurs) or change in the political stream.

In the case of the proposals regarding a new women’s prison, a ‘policy entrepreneur’, possibly two, emerged from the beginning of 1993 within the prison management. The importance of key individuals – for example, in the establishment of the in-house discussion group – is clear from the interviews conducted. In fact, the group’s meetings began several months prior to the Minister for Justice convening the publicly announced Ministerial Steering Committee/Advisory Group.

Policy Window and Coupling

As noted earlier, policy windows are opened by events in either ‘the problem stream’ or ‘the political stream’. The implementation of an initial policy solution (that is, the refurbishment of the women’s prison) temporarily pulled the blinds on the window, as it were. However, in reality, ‘the problem’ – the severely inadequate conditions in the prison for women – still existed. Changes in the streams – mainly, as noted, in the political stream – allowed for the issue to re-emerge onto the policy agenda, and this eventually led to the building of the Dóchas Centre.

While the claim cannot be definitively made, it would seem that the entrepreneur(s) and the in-house discussion group – sub-government – were crucial in the ‘coupling’ (attaching) of their blueprint document (the solution) to the problem of the conditions for women in prison. What is clear is that chance also played some part in the process.

‘Serendipity’ and ‘Chance’

Kendall and Anheier38 highlight the role of ‘serendipity’ in the policy process and Kingdon refers to the role of ‘chance’. Clearly, it would be wrong to suggest that the Dóchas Centre came about by accident, but it is not unfair to say that there were elements of chance in the process – elements which fortunately served to bring about the building of the Centre.

Anthony Downs notes that problems often fade away after a short period of public attention, especially when there is a realisation of the financial cost of taking action.39 In December 1994, the Labour Party withdrew from coalition government with Fianna Fáil, and in January 1995, without a General Election having been held, a new coalition, comprising Fine Gael, the Labour Party and Democratic Left was formed. Nora Owen TD (Fine Gael) was appointed Minister for Justice. To the extreme annoyance of the new Minister, the provision of funding for the planned new prison for women was deferred by the Minister for Finance, Ruairi Quinn TD (Labour).40 Nora Owen threatened to resign over this and other budgetary cuts.

At that point, the view might easily have been formed within Government that the refurbished wing for female prisoners in Mountjoy would be ‘good enough for now’. However, eight months later, in January 1996, the Government announced a ‘new crime package’, which promised a 10 per cent increase in prison capacity and re-instated the aim of providing a new prison for women.41

The need for more places for young men in St Patrick’s Institution may have been a factor in the decision at that time. In the announcement of the ‘crime package’, there was reference to the fact that 30 more spaces for young men would be made available in St Patrick’s Institution, with a further 55 additional spaces within eighteen months.42 While not explicitly stated, it is likely that it was being assumed that providing these 55 additional spaces would necessitate the complete removal of the women’s prison from St Patrick’s.

In the months prior to the final signing of contracts, other events served to keep the issue of a new prison for women to the fore. A second death by suicide in the women’s prison in May 1996 again focused public and media attention on the conditions existing in the prison.43 Following the death of the journalist, Veronica Guerin, the Government responded with a Press Release on 2 July 1996 which, alongside a series of ‘tough-on-crime’ measures, confirmed Cabinet approval for the capital funding for the new women’s prison.44

Conclusion

Kingdon’s multiple streams framework for understanding the policy process separates out (i) the defining of the ‘problem’, (ii) the ‘policy’ solutions being presented and (iii) the ‘politics’, the political ‘buy-in’ for proposed solutions. Central to the process is the person or persons who can couple a solution to a problem and find a ‘policy window’ – an opportunity through which the policy can be advanced.

It is difficult to identify the ‘definitive moment’ in the genesis of the Dóchas Centre. However, it is clear that there was a prolonged phase during which ‘the problem’ was identified and possible solutions presented and tested. The significant change in the ‘political stream’ which occurred with the appointment of Máire Geoghegan-Quinn as Minister for Justice, and administrative changes which occurred around the same time, meant that ideas for a more radical response could fall on ‘fertile ground’. Crucially, the emergence of a ‘sub-government’ element and of policy entrepreneurs bound the solution to the problem. The involvement of ‘outsiders’ gave breathing space to the ‘insiders’.

The refurbishment of the women’s prison in the 1990s was seen as an exercise in using ‘gallons of paint’ to disguise the old system, albeit at a cost £2.5 million.45

Today, the Dóchas Centre is severely overcrowded, with 130 women in a facility designed for 81 to 85. In April 2010, the former Governor of Dóchas, Kathleen McMahon, expressed her concern that, due to the deterioration in conditions in the Centre, some of the problems which existed in the old women’s prison, such as coercive relationships and self-harm, were re-emerging.

The initial response to increased numbers in the Dóchas Centre was to develop ‘dormitory style’ accommodation. This option was, however, rejected by the new Director General of the Irish Prison Service in late 2011/early 2012.

The Irish Prison Service’s Three Year Strategic Plan 2012–2015 states that during 2012 and early 2013 the focus of the Service will be on reducing overcrowding in a number of named prisons, including the Dóchas Centre.46 In addition, the Strategic Plan gives a commitment that the Prison Service, ‘working in partnership with the Probation Service and other stakeholders in the statutory, community and voluntary sectors will seek to develop a strategy for dealing with women offenders’.47 Crucial to the realisation of these commitments will be factors outlined earlier – clear articulation of ‘the problem’, value acceptance and technical feasibility of the possible solutions, key individuals who promote a reform agenda and, finally, the political opportunity (window) through which reform can be pushed.

Notes

Eoin Carroll is Advocacy and Social Policy Officer with the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice.