Kevin Hargaden

Insider to Outsider: Sinéad O’Connor’s Iconoclasm

For a pop musician, one of the most coveted gigs is headlining the American TV show “Saturday Night Live”. If you get invited to that stage, you know you’ve made it.

This makes it all the more remarkable that when a 26-year-old woman from Glenageary in south Dublin reached that pinnacle, she used the opportunity to enact one of the most potent protests of the modern age. Sinéad O’Connor was meant to sing her newest hit song and receive the acclaim. Instead, she used the rare opportunity afforded by the fact that SNL was broadcast live. She changed the lyrics of the Bob Marley song she was singing, so that it referred to child abuse instead of racism. Then she took out a photograph of the beloved Polish pontiff, John Paul II and tore it to pieces, throwing the fragments at the camera while calmly declaring, “fight the real enemy”.

The studio audience did not applaud. Eye-witnesses report that the air went out of the studio. Executives watching at home remember jumping out of their chairs in dismay. This was 1992.

The reaction was immediate and immense.[1] The New York Daily News put it on its front page and compared it to terrorism. The following week’s show was hosted by the actor Joe Pesci. It opened with him holding the same photograph that was torn apart repaired. He then proceeded to tear a photograph of Sinéad, to riotous applause, before finishing with the warning that had he been present, he “would have gave her such a smack”. Frank Sinatra said that he wanted to “kick her ass”. The TV producer Jonathan King declared that she “needed a spanking”. Her next public appearance was at a concert in honour of Bob Dylan. As she took the stage, the crowd began to boo loudly.

One moment, Sinéad O’Connor was the ultimate insider – a world-famous pop-star with an adoring public, an iconic place in popular culture, and a future where she could do anything she pleased. The next moment, the very same woman found herself outside. She was never invited on SNL again. She had only one more hit single in the US, associated with the movie In the Name of the Father, and it only reached number 24.

It was two years before the UTV documentary “Suffer the Children”, three years before Brendan Smyth would be arrested, and was fully a decade before the Boston Globe revealed the extent of ecclesial abuse in Massachusetts. Almost three decades later, few would deny the power of this piece of political performance art. Of course, the scandal of ecclesial abuse is complex and a full account requires all sorts of nuance and clarification. But a protest is not meant to be a comprehensive analysis. And no one would question the principle and courage involved in her act. In her recent memoir it is clear that this was no hasty blunder. She understood the consequences of her inflammatory gesture. She grasped that it would radically transform the opportunities offered to her. She was not unaware that the scale of the scandal meant that personalising attention solely on a single figure like the Pope was not the optimal path to justice. But when it felt like no one was paying attention, and she had people’s attention, she felt morally-bound to do whatever it took to get people to look at what was only half-hidden.[2]

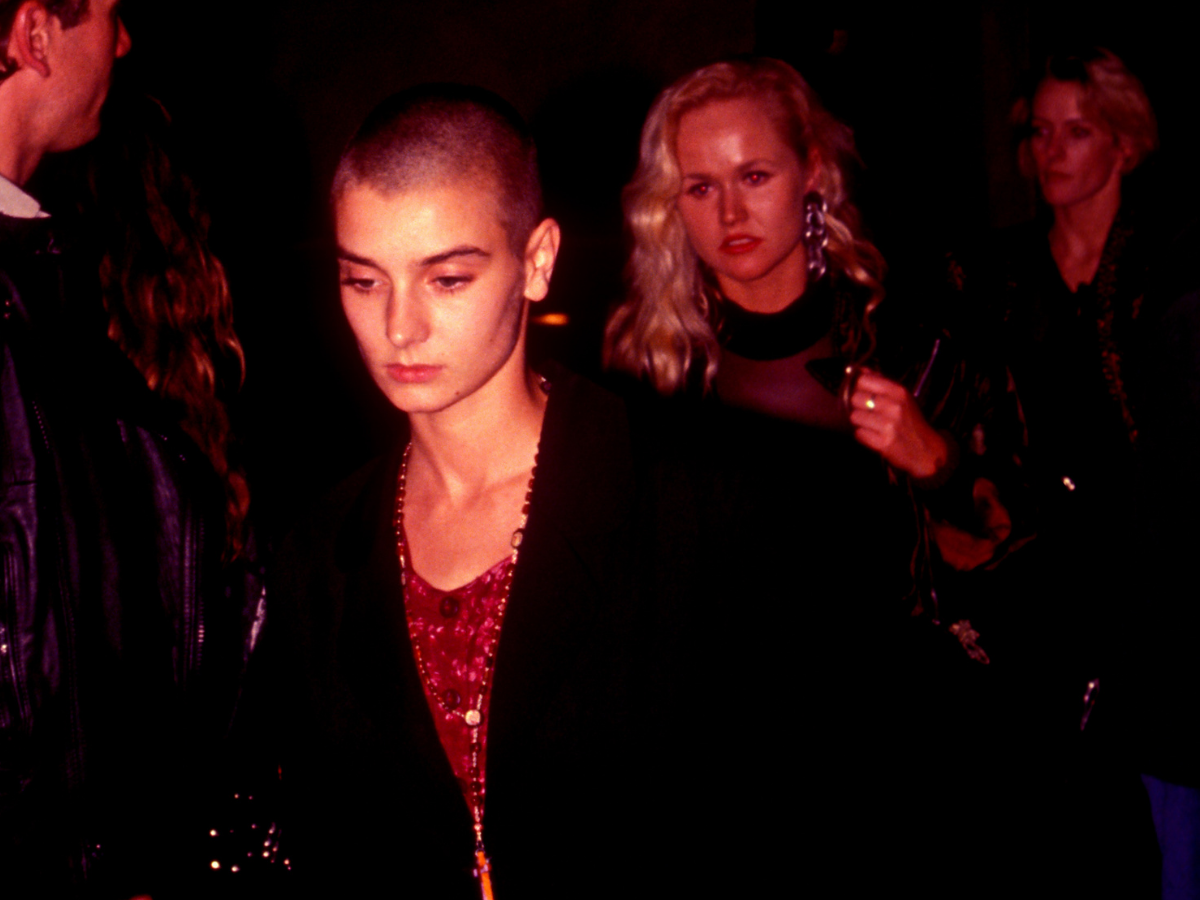

Sinéad O’Connor in LA a few months before her protest on SNL (Bart Sherkow: Shutterstock 1397768630)

What I am about to claim is not nearly as controversial as it would have once been, in part because the subsequent revelations have vindicated Sinéad and in part because the church’s own self-understanding has shifted as we have been de-centred from the sources of societal power. But Sinéad O’Connor embraced the loss of her insider-status to stand in solidarity with victims who were entirely outside of our collective gaze. To make that protest against the ungodly crime of ecclesial abuse she drew on one of our most significant symbols of religious propriety and shattered it. In the days before social media, Sinéad O’Connor incited a viral mob against herself in the hope that when the dust cleared, someone would pursue her line of reasoning, investigate the rumours that were everywhere whispered, and bring justice and solace to those who had been harmed by people who presented themselves as healers. Sinéad O’Connor confronted us with a truth in a way that shockingly exposed our corruption. It was prophetic. Society despised this message because society could not confront this truth. Understanding all this, she went ahead with it. She embraced the exclusion that came from this act. Given a choice between keeping quiet and staying on the inside, and standing up for those on the margins but being cast to the outside, Sinéad chose the narrow path.

There is something of Jesus’ sense of irony at play in that one of the most powerfully Christian acts to ever occur on live television, was when Sinéad O’Connor tore up a picture of the pope.

Fratelli Tutti and Social Friendship

Like all of Francis’ letters, his latest encyclical – Fratelli Tutti – has many sides. I suggest that a particularly relevant approach from an Irish perspective is to read Fratelli Tutti in terms of insiders and outsiders, those who are included and those who get excluded. The heart of this letter lies in Francis’ idea of social friendship. In this paper I want to consider how social friendship might apply in Ireland.

I am going to argue that our society has spent the last century busy in the project of constructing an Irish State, but our approach to that has been focused on negative identity building, deciding on who we are and what we are about based on reaction against others. This is most clearly seen in the way that the church enacted the violence of the State – with the almost unanimous approval of the people – in a range of institutions that housed those we did not desire to include. My approach here is an attempt to honour the theological priority towards self-accusation. We consider what is blocking our vision before accusing anyone else of blindness.[3]

Yet we must recognise that whatever we call the contemporary quasi-secular liberal power nexus that replaced the quasi-devotional conservative power nexus has not evaded this negative inside-outside dynamic. We pride ourselves on our tolerance the way our grandparents prided themselves on their orthodoxy, but the self-congratulation must look very different to the thousands of families who are homeless or stuck in direct provision centres.

In summary, here is my argument: The Irish State, at least since its founding, has been happy to do whatever it takes to keep business turning over, and that has always involved excluding a large minority of people in institutions, in deprivation, in scorn, since their existence challenges the stories we like to tell about ourselves. And Fratelli Tutti offers an alternative account of how to order the shared space of compromise we call politics. Social friendship is a potential repair kit which could play a part – a small part, because I hope the future church will learn from the past church how dangerous it is to be feted as important and central and influential – in seeing Ireland’s second century embrace a more humane way of forging identity.

I will make this argument by briefly summarising Fratelli Tutti with a focus on the concept of social friendship, then sketching how we have utilised the power of casting others out to underline who is in, and suggesting in the close that what Francis is alluding to is drawing from the very central well of the Christian faith. If we want to build a society that doesn’t nourish the insiders by feeding on the flesh of outsiders, a religion about a God cast out might have some surprisingly relevant contributions to make.

Fratelli Tutti was published in Assisi on St Francis’ feast day.[4] I suspect in time it will come to be understood as a sort of “Greatest Hits” for this Pope’s project. It draws heavily on his addresses and it echoes the themes that careful readers of his other encyclicals – Lumen Fidei and Laudato Si’ – will recognise. It spans eight chapters, so it continues Francis’ habit of writing longer encyclicals than his predecessors.

It is notable for how it treats events still unfolding. Francis engages the pandemic which was at its nightmarish stage in northern Italy as he was drafting it. Some contemporary issues are just so concrete that to avoid them would be impossible! And in this instance, the encyclical is undoubtedly strengthened by this engagement because the spread of Covid-19 allows us to see clearly – if we dare to look – how we are all in the same boat. As such, focusing on the pandemic strengthens his main point: that all humans are brothers and sisters to each other and every tradition or institution or ideology that seeks to obscure that basic fact must be challenged.

The Encyclical Summarised

The letter begins with chapters of diagnosis, and Francis is clear that we are under dark clouds. Not just the pandemic, but the general trend towards limitless consumption, the instrumentalisation of other human beings, and the exploitation of the natural world constitutes what he calls a throwaway culture where discarding objects becomes so prevalent we end up discarding people.[5] We wander the world seeking our utility, abandoning anything and everything that we deem useless, rejecting all binding obligations but our own fulfilment.[6]

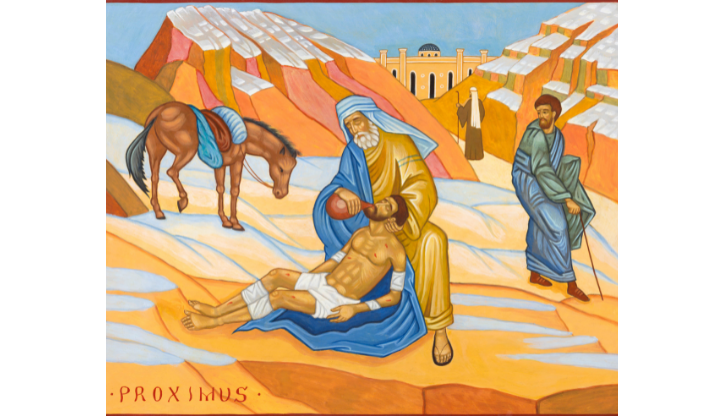

His treatment involves taking us to one of the world’s best known stories, in the hope that we might see it again with fresh eyes. All of chapter 2 is dedicated to Jesus’s parable of the Good Samaritan, which makes sense because it was the short story he told to answer the question: “Who is my neighbour?” Francis recommends we identify ourselves with the Samaritan, who avoids the indifference of the religiously and socially respectable people who walk by the dying man. The moment of truth for all our approaches to life is not whether or not they represent coherent philosophies or popular politics, but whether when faced with suffering “will we bend down to touch and heal the wounds of others?”[7]

Chapters 3 and 4 work out how this applies. The openness to encountering the other is at the heart of enacting the Good Samaritan ethic. It is important to note how the different pieces fit together. What Francis is proposing is that attentiveness to the suffering of those around us is the way we live out being neighbours. But by engaging in neighbourly openness, those relationships can be transformed into true fraternity, not just neighbours who live without discord in proximity to each other, but an extended family capable of showing love to each other. This is a profound implicit critique of our present political culture, that even at its most noble never dares to suggest we have this kind of obligation to the other.[8]

The second half of the letter represents a series of tangible calls to action. Along the way, Francis makes important elaborations to Catholic Social teaching. After this letter, while the church has not committed to non-violence, it is practically impossible to imagine a modern war being declared just.[9] It is categorically impossible to argue for the death penalty.[10] Chapter 5 focuses on a better kind of politics, one not driven by pragmatic concerns about winning the next election but committed to seeking and implementing charity and truth.[11] Chapter 6 extends that to the individual and their community, calling on people to cultivate an approach to living together grounded in dialogue, grounded in listening before we speak.[12] Chapter 7 notes that the “otherness” which we must seek to welcome is not always exotic. “Renewal” is the key word here, recognising that the narcissism of small differences mean that we often satisfy ourselves on our magnanimity in abstract, talking about how open we are to the Others we never meet, while furiously despising the much nearer Others we cross paths with every day.[13] The final chapter may turn out to be the most decisive in the historical frame and it is the section which does most to respond to the obvious criticisms that we may make about how the institutional church has hardly role-modelled social friendship in its own actions in recent decades. It proposes that the role of religion in our world is to build this sense of fraternity and draws on the radical project of inter-religious dialogue Francis has begun with the Grand Imam of Al Azhar, Sheik Ahmad el-Tayeb.[14] We are back here at the beginning: since we are all creatures of the one creator, we share in common far more than what divides us and we are only ever being realistic about that fact when we encounter the Other as a sister or a brother.

One of the risks with a rapid summary of the encyclical is that we become baffled by how these threads tie together. But I propose that the core of the argument Francis is making is his concept of social friendship. Social friendship is his way of articulating the synthesis that is required between the personal and the political – so that our interventions on the crises of injustice we face operate both at the level of authentic human friendship and at the level of meaningful political and social transformation, grounded on the “acknowledgement of the worth of every human person, always and everywhere.”[15]

Generalising wildly, two approaches are typically available to us politically. People on the Right focus on personal responsibility and the potential of the individual. People on the Left focus on structural responsibility and the potential of the collective. Social friendship is not a naïve both-and-ism that seeks to satisfy each side of the spectrum. We misunderstand if we imagine that the Pope turns first to the right-winger and says, “you are correct” and then to the left-winger to say, “you too are correct”.

His claim is much more audacious. The conservative has one vision for justice where the demands placed upon the individual have limited societal implications. The liberal has another vision of justice where the demands placed on the society have limited individual implications. And Francis is implicitly suggesting both are wrong. Dwelling on the Good Samaritan, he presents a view of political intervention grounded in attentive hospitality. The outcast Samaritan is the hero of the story because unlike the religiously devout and socially acceptable lawyer and priest, he does not just walk by. Social friendship presents this politics of solidarity – that our communities can “be rebuilt by men and women who identify with the vulnerability of others, who reject the creation of a society of exclusion, and act instead as neighbours, lifting up and rehabilitating the fallen for the sake of the common good.”[16]

This is a political stance grounded in the respect of the difference embedded in the other, but sees there is not a threat but an opportunity. We do not need to protect ourselves from otherness, rather we must generously seek to truly encounter it.

How Outsiders Make Insiders

How do these concepts of social friendship, insiders, and outsiders play out in Ireland’s second century?

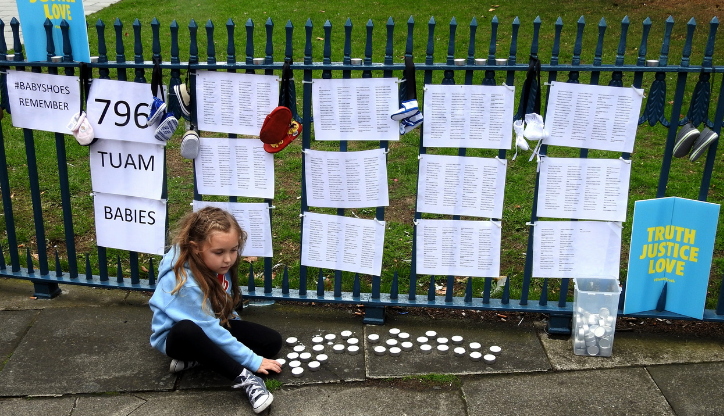

Reading Fratelli Tutti when it was first published, I had a notion that its relevance for Ireland was not just in its contemporary engagement with crises like the pandemic. That inchoate sense took form when the Mother and Baby Homes report was published.[17] It was released as I was working on an odd little project, writing an essay about how childbirth is depicted in Irish movies.[18] What I found in that research was that Irish films don’t typically depict labour and birth in the rosy tones that we know so well from Hollywood. Having watched every Irish film from the last fifty years that feature such scenes, I can declare that in practically every single case, the arrival of the new human life is ambivalent. The one superficially stereotypical scene where a family rushes in joyfully to greet the wee baby comes at the end of The Snapper, Stephen Frears’ 1993 hilarious and harrowing adaptation of Roddy Doyle’s acclaimed novel. To avoid spoilers, I will simply say that the baby who inspires such delight was not conceived in happy circumstances.

The Mother and Baby Homes Report was noteworthy because of its clarity in describing how this system – from its genesis in the moral imagination right out to its implementation in high walls around the building and doors that locked securely – could only be constructed and maintained with widespread support within the population. And the “church” that is implicated is every church, not just Roman Catholicism. Presbyterians and Methodists and many Anglicans were involved in this quasi-carceral system. My conclusion reading this report was that the only traditions untouched were the Orthodox and the Pentecostals and that was largely because they were tiny populations at the time.[19] Every Christian tradition was eager to play their role by being diligent and dutiful citizens upholding the moral propriety of their society by punishing the outcast.

“Stand 4 Truth” rally outside the Garden of Remembrance, held on August 26th 2018, as Pope Francis visited the same part of Dublin. (Dirk Hudson, Shutterstock 1165415371)

Reading the forensic assessment of how evangelical Christians like myself – from churches where I regularly preach or visit – founded and operated homes that enclosed pregnant women in captivity was truly depressing. For about a fortnight I had my own mini-crisis of faith. How could it be that a religion established to worship a child born out of wedlock to a mother who stood in disgrace among her society could end up sustaining that same societal disgrace? The Report is strong in how it describes the complexities at play in these women’s detention, which was very often not penal. In most cases, they could leave if they wanted. But if they left, no one wanted them. As Cole Porter famously sang, “Birds do it. Bees do it. Even educated fleas do it”. But for most of the first century of what we call Ireland’s liberation, young women who “fell pregnant” – to use our theologically resonant colloquialisms – became captive to these institutions. This is my explanation for why Irish filmmakers are so ambivalent about labour: the newborn is often the most unwelcome Other.

My crisis lifted when the coin dropped. Fratelli Tutti’s focus on the Samaritan – that outcast who stopped and attended and cared for the suffering one when all the diligent and dutiful citizens passed right on by – was the antidote to the kind of violence which we find detailed in this and every other report that the State commissions into its past. Francis’ insistence that the Other does not confront us with a threat but an opportunity to enact the Gospel’s culture of encounter is the word we need to hear right now. It is the word we needed then, too. That’s one of the ways we can test to see it is true.

Much more would need to be said to lock this claim down in a fashion that satisfied the academic historians, but I think this is a hypothesis worthy of consideration: for Ireland’s first century, we constructed our sense of self, we developed a collective “we”, by means of othering groups of people we could call “them”. Depending on the situation, the them could be the English, could be Protestants, could be unwed mothers, could be delinquent children, in one infamous case of popular protests in Co. Leitrim, it was fans of jazz music.[20] Otherness was the threat that provoked in us the sense of community that secured us.

McQuaid’s Catholicism is long gone, but I further propose that this dynamic is not yet extinct. The same kind of kneejerk and groupthinked collective moral policing is still to be found. My generation and those younger than me take great pride in their self-understanding as being progressively tolerant in a way that is formally parallel to how my grandparents’ generation took great pride in their collective self-understanding as devoutly orthodox. Ireland then was an example to the other nations, unique because of our frugal faithfulness. Ireland today is presented as an example to the other nations, unique because of our efficient inclusivity. We used to cobble our self-esteem together by contrasting ourselves against the secularising English. We now cobble our self-esteem together by contrasting ourselves against the conservative European nations who aren’t on board with our progressive agenda. But the point is that we are still defining ourselves against the Other.

Such an argument is dissatisfying in how vague it is; how prone it is to confirmation bias. But we do have grand formal parallels to the Mother and Baby Homes in our midst which signals how we have not progressed beyond the insider/outsider dynamic. After asylum seekers began arriving more commonly in 1997 – well within the era of the secular Celtic Tiger – the government established a system to house candidates as their claims for refuge were assessed. Our secularity can be demonstrated by the fact that the churches were not called upon to provide this service. Instead, in 2000 it was outsourced for profit.[21]

We came to call this system Direct Provision. Like previous forms of institutionalisation, it is not legally a form of captivity. Asylum seekers can leave. But if they do, they are utterly on their own. Just like the previous inhabitants of earlier systems. Many reports can be found which assess the centres in various ways, just like with the old system. But the suspicion persists that these reports, collectively, are replicating the lawyer and priest dynamic of Jesus’s famous parable and finding reasons not to look too closely in case they see undeniable human suffering.

After the Global Financial Crash in 2008, Ireland engaged on a decade of austerity. Public housing was defunded. Care for those who could not compete in the housing market was increasingly provided by the market itself through a subsidy to private landlords called Housing Assistance Payment (HAP). Activists close to the issue were alarmed at this development. At the time, Fr Peter McVerry, SJ predicted what he called a tsunami of homelessness. A Labour Minister for Housing took to the press to criticise his claims that homelessness could top 5000. It spent a year above 10,000 before the pandemic.[22] The Government has tried every available solution to resolve this crisis except the obvious one – returning to serious and ambitious public housing. Each of these schemes in different ways replicate institutionalisation, except we don’t call it that because the institutions are run by charities or corporations. Anyone who has spent any time in these homeless hubs or emergency accommodation facilities – or anyone who has taken the time to listen to those who have – knows that abuse is rampant. But we don’t take the time to stop and attend. We are dutiful and diligent citizens after all.

So: the Others are still among us. The asylum seeker and the homeless person present a clear threat to our self-understanding as citizens of a prosperous and cosmopolitan Western Republic. Better out of sight so as to be out of mind. Many of us will have to feign surprise if a Commission is convoked in the future to consider the abuses in the systems erected under our watch. Many of us suspect that those future historians will say, “The records suggest that such systems had widespread support. It was considered impossible to offer hospitality to the refugee or housing to the homeless without threatening the foundations of our moral order, which is our prosperity.”

It’s different to the 20th century Othering; we are concerned now mostly about profit instead of piety. But it is also the same.

Fratelli Tutti’s concept of social friendship intervenes at just this point. If we can cultivate a political culture that sees Otherness as truly distinct – so much of the contemporary liberal project wants to create a homogeneity out of difference – and still as valuable in itself because of that, then we would be moving toward a culture of encounter. Jesus never suggests the Samaritan was a Judean. He insists instead that the Judean can only be Judean by attending to the example of the Other, the different one, the Samaritan. In Jesus’ telling, the very one they wish to cast out, the enemy that must be vanquished, is no longer just a foil against which to build in-group solidarity. The Other is the difference they must encounter to discover who they are truly called to be.

Social friendship is thus a political philosophy that holds that both structural problems remedied at the level of policy and social issues addressed at the level of personal relationship matter. It is not either/or. One is not inside while the other cast out. They go hand-in-hand. The space between their difference – the structural and the personal – is the space where we encounter the Other and discover they are our neighbour, even more, our sister and brother. The first story in the bible after Eden has Cain respond to God about the missing Abel, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”[23] God never corrects him. Some errors are so self-evident, you have to actively avoid the truth.

Throughout Ireland’s first century of independence, Otherness was the threat that provoked in us the sense of community that secured us. In our second century, social friendship is a means to transcend those stark and violent dichotomies of insider and outsider, framing our politics more realistically as the process by which different neighbours negotiate the loves they share in common. As Francis counsels: “Let us seek out others and embrace the world as it is, without fear of pain or a sense of inadequacy, because there we will discover all the goodness that God has planted in human hearts.”[24] We are not aliens to each other, but siblings.

The Deep Theology of Social Friendship

Coming as an outsider to the world of Catholic Social teaching, one of the very surprising things to me is how the theological content of the Papal encyclicals is often passed over. I sometimes get the impression that many in the church see this social tradition as a sort of superficial outer layer that serves some apologetic function but is distinct from the real business of theology and the church. Were we to analyse Fratelli Tutti dogmatically, we would quickly find that beneath the provocative claims about populism and property, nuclear armaments and death penalties, lies a profound theology of the cross.

The dynamic that Francis highlights in his discussion of the Good Samaritan is that the outsider is the one – the necessary one – who saves the insider in peril. One is reminded immediately of the theological work associated with Miroslav Volf.[25] He wrote his groundbreaking study, Exclusion and Embrace, as a Croat in exile during the Yugoslav war. The stakes at play in approaching the Other as a sibling waiting to be encountered can’t really be higher than during ethnic cleansing. But in this book, Volf meticulously describes how Jesus is an insider, conversant in all the treasures of Israel, who willingly and intentionally dedicates himself to a path of identification with the outcasts – the sinners and tax collectors, the prostitutes and the lepers, Roman centurions and even, at times, Samaritans – to the dismay of the status quo and his own followers. We now understand that this is in microcosm what the incarnation means on a cosmic scale, as Paul explains in the famous passage in Philippians 2:5-11. Although being in very nature God, Jesus did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage. Rather, he made himself nothing. He took on the very nature of a servant, born and raised as a human. And being found as a man, by appearances like any other, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death. Not any death; but death on the cross – a death so disgraceful and disreputable that Romans would never administer it to a citizen regardless of how horrible their crimes.

The ultimate insider – who enjoyed the heavenly company of his Father – is cast out, beyond the walls of Jerusalem, outside of the city, beyond the borders of civilization, rendered like an animal to be sacrificed. On the cross we find God become man, abandoned, discarded, excluded and set apart from all humanity. On the cross we find God become man with his arms outstretched, ready to embrace us. Not in spite of that othering, but through it.

This is the deep dogmatic core of social friendship. It is only in our identification with the outcast and our movement towards the margins that we begin to see what is at the centre of God’s Kingdom: the revolutionary reconciliation that makes enemies into neighbours and neighbours into family.

Icon of the Parable of the Good Samaritan in Chiesa di San Pietro in Bologna. (Renata Sedmakova, Shutterstock 1083278969)

And what is the specific role of church in all this? Is its role to be the leader of the reconciliation to exemplify the kind of loving social friendship that everyone ought to imitate? By no means! The church ought to be part of the dialogue, but as a function of the fact that everyone needs to be invited to the table.

Whether he meant to or not, Francis has given the Irish church a sharp and helpful word to describe the approach they should take to their contribution. At the start of chapter 7 we read that organisations who are at risk of “empty diplomacy, dissimulation, double-speak, hidden agendas and good manners that mask reality” in the aftermath of “their own regrets” must cultivate what he calls “a penitential memory.”[26]

He intends these words to apply to entire societies that have been marked by conflict but I propose that we prayerfully adopt them as a reparative therapy, a serum to support those of us called to lead organisations which are embroiled in the scandalous crimes of past decades. It is no easy task, but repentance is always liberation.

Conclusion

When the crowd began to boo Sinéad O’Connor in Madison Square Garden, she said that she felt she was going to vomit. She could not go on. The acclaimed country singer, Kris Kristofferson, was just off stage. He saw what was happening. The organisers asked him to go and take her off the stage. In that moment, he too, instinctively, knew what to do. Faced with a scapegoat, he identified with her. He stepped out of the shadows, into the spotlights. He walked across the stage and put his arm around the young woman – who he did not know – and hugged her. He said he only had one message: “Don’t let the bastards get you down.” She took courage.

The video footage is remarkable. Instead of singing with her band, she takes the microphone and sings the same Marley song from the previous week – the anti-racism anthem War – but this time acapella. Her unadorned voice, insistent with truth, rises above the jeering crowd. Again, she repeats her claim that every institution that sanctions child abuse must be toppled. The fury of the crowd seems to grow. At the end of the short song, Kristofferson is there again. He throws his arms around her, utterly identifying himself and his ultimate insider-status with this one who is scorned for telling the truth. At one point she pulls out of the hug. She turns away and gags.[27] Kristofferson simply hugs her again.

Humans, it seems, cannot inhabit our status of insider without framing it against outsiders. This is one of the reasons why we should be sceptical of easy claims grounded in concepts like inclusion and tolerance – not because those are not virtuous things to achieve – but because if we believe we arrive at them without difficulty we are deluded. In that state, we can’t even see the truth of things, the reality of those we leave outside while acclaiming our own largesse. The actions that flow from Fratelii Tutti are diverse but we can see some immediate possible steps – spending our resources on aligning with the outsiders, consciously engaging in penitential memory as a spiritual discipline to heal us of our yearning to be insiders, and supporting the policies or cultural trajectories that encourage social friendship.

The insider/outsider dynamic described by Francis is likely to intensify. Elsewhere in this issue, Dug Cubie engages the complexities at play in mass displacement. This dynamic will surely increase as the climate catastrophe accelerates. Transcending our insider/outsider dynamic is essential in this context not simply to create a culture of encounter able to extend hospitality to those who need it, but because the Far Right will seek to exploit this crisis and intensify the culture of fear.

When those extremist insiders seek to gain from the fear of movements of displaced populations, what will we say? If we continue to refine the business as usual politics we have deployed since Independence, we can predict the answer. We will be diligent and dutiful in turning a blind eye to the suffering of brothers and sisters, insisting instead they are aliens, strangers, others. Francis talks in Fratelli Tutti of how “new walls” are being erected for “self-preservation.”[28] That temptation will be irresistible if do not cultivate some version of social friendship.

The English novelist John Lanchester published a short novel in 2019 called The Wall.[29] It imagines a not-too-distant future where a climate crisis event referred to only as “the change” had taken place. A 15 metre wall has been erected around the entire island of Britain, rendering the UK a literal fortress. Consumed by the urge for self-preservation, the British people lose their humanity. Interestingly, Lanchester leaves the reader in the dark about the actual scale of refugees arriving. The facts don’t matter so much once the fear-filled discourse passes a certain threshold.

This is a fable. This is not how it is going to be. But like any good fable, it actually tells us exactly how it is going to be. If we resist social friendship and embrace instead isolation or preservation, erecting barriers that divide us from them, violence will follow. We need not be prophets to know these results. We have spent Ireland’s first century conducting the experiments. As Francis warns: “Those who raise walls will end up as slaves within the very walls they have built. They are left without horizons, for they lack this interchange with others.”[30] Social friendship is not all we need to navigate the coming era of migrations in our common home, but by inculcating a culture of encounter, it is an essential component and certainly one to which the Christian is summonsed.

You can download a pdf of this article here

Footnotes:

[1] I am reliant on a Twitter thread by the writer Audra Williams for my reflections on O’Connor’s SNL appearance. Audra Williams, “In 1992, Sinead O’Connor Ripped up a Picture of the Pope on Live Television, in Protest of the Rampant Child Sexual Abuse the Catholic Church Was Actively Covering Up.,” Tweet, @audrawilliams (blog), January 20, 2019, https://twitter.com/audrawilliams/status/1086857070362705921; O’Connor’s own account of the experience is found in: Sinéad O’Connor, Rememberings (Dublin: Sandycove, 2021), 191–93.

[2] Describing her thought-process ahead of the protest, she writes: “I know if I do this there’ll be war. But I don’t care. I know my Scripture. Nothing can touch me. I reject the world. Nobody can do a thing to me that hasn’t been done already. I can sing in the streets like I used to. It’s not like anyone will tear my throat out.” O’Connor, Rememberings, 178.

[3] Matthew 7:5.

[4] Fratelli Tutti means “All Brothers”. The British theologian, Theodora Hawksley, pointedly proposed that the English translation should be “All my Bros”. Theodora Hawksley, “Why the Title Matters,” Theodora Hawksley (blog), October 5, 2020.

[5] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti (Assisi: Vatican, 2020), §20.

[6] §27 is particularly acute in its description of how we erect walls to avoid encountering otherness and thus become slaves to our own greed.

[7] Pope Francis, §70. It is also worth noting how in §75, Francis spends time considering the people that Luke overlooks – the robbers.

[8] This is where we find Francis’ discussion about relativized property rights (§120) and nationality (§121). Chapter Four particularly looks at migration, proposing that some form of global governance is required (§129-132).

[9] Pope Francis, §258.

[10] Pope Francis, §263–70.

[11] The marketplace can’t resolve every problem (§168) and our engagement on poverty must be with, not just for, the poor (§169).

[12] Kindness as the antidote to anxiety: §222-224.

[13] Consider §241, on how social friendship does not pass over oppression.

[14] See §285.

[15] Pope Francis, §106, emphasis original.

[16] Pope Francis, §67.

[17] Yvonne Murphy, William Duncan, and Mary E. Daly, “Final Report of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes” (Dublin: Department of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth, 2021), https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/d4b3d-final-report-of-the-commission-of-investigation-into-mother-and-baby-homes/.

[18] Kevin Hargaden, “Birth on Screen: How Childbirth Is Depicted in Irish Film,” in Birth and the Irish: A Miscellany, ed. Salvador Ryan (Dublin: Wordwell, 2021), 346–50.

[19] Kevin Hargaden, “Evangelicals and Church Abuse”, Vox April 2021 (Issue 50): 24-26.

[20] Jim Smyth, “Dancing, Depravity and All That Jazz: The Public Dance Halls Act of 1935,” History Ireland 1, no. 2 (1993): 54.

[21] Steven Loyal and Stephen Quilley, “Categories of State Control: Asylum Seekers and the Direct Provision and Dispersal System in Ireland,” Social Justice 43, no. 4 (2016): 70.

[22] JCFJ, “1/22 After #GE2020, We Have Been Trawling through Our JCFJ Archives. For 40 Years We Have Been Fighting for Social Justice in Ireland, and through the Lens of Peter McVerry, We’ve Watched the Housing Crisis Develop up Close. A Thread on Why We Need a Total Change in Direction: https://T.Co/V4YDttcUNt,” Tweet, @JCFJustice (twitter), February 11, 2020, https://twitter.com/JCFJustice/status/1227284123280080905.

[23] Genesis 4:9.

[24] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, §78.

[25] Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace (Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 1996), 75.

[26] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti §226.

[27] “I almost barf on him as he gives me a hug.” O’Connor, Rememberings, 193.

[28] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, §27.

[29] John Lanchester, The Wall (London: Faber and Faber, 2019).

[30] Pope Francis, Fratelli Tutti, §26.