Introduction

As soon as the modern prison was established, concerns about the treatment of prisoners were expressed from many quarters. With a focus on Irish prisons and prisoners, this essay examines some of the people and organisations involved who conveyed compassion for the plight of prisoners, advocated for improved prison conditions, and supported penal reform. It begins by sketching out some early philanthropic and charitable endeavours. It then details support networks for people convicted of politically motivated activities before reviewing campaigns for improved conditions for those who were termed “ordinary” or “social” prisoners. The essay concludes with consideration of prisoners’ advocacy organisations and support movements today.

Early advocates of reform were mainly inspired by religious belief, motivated by charitable and philanthropic endeavours. With the rise of physical force nationalism in the 19th and 20th centuries, prison conditions and the status of politically motivated prisoners in Britain and both jurisdictions in Ireland came under scrutiny. Although not as well researched, in the 1970s there were attempts to mobilise “ordinary” prisoners to improve what were generally accepted as deficient penal conditions. Contemporary groups concerned with the plight of prisoners range from charitable organisations with a social justice focus, to abolitionist movements based on allyship and solidarity. While punitive approaches to punishment ebb and flow, there have always been people and organisations who expressed and continue to show concern for the plight of prisoners.

“Stop doing wrong; learn to do right”

In the early years of the prison, religious faith and spiritual devotion were significant motivations in those promoting relief for prisoners. Opened in 1829, the Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia was designed with individual cells, as the “[t]otal solitude before God was supposed to effect a conversion of the criminal’s moral sensibilities.”[1] However, as soon as the modern prison was established, its limitations became apparent, and the optimism of its founders soon faded. Prison reform was necessary for prisoner reform.

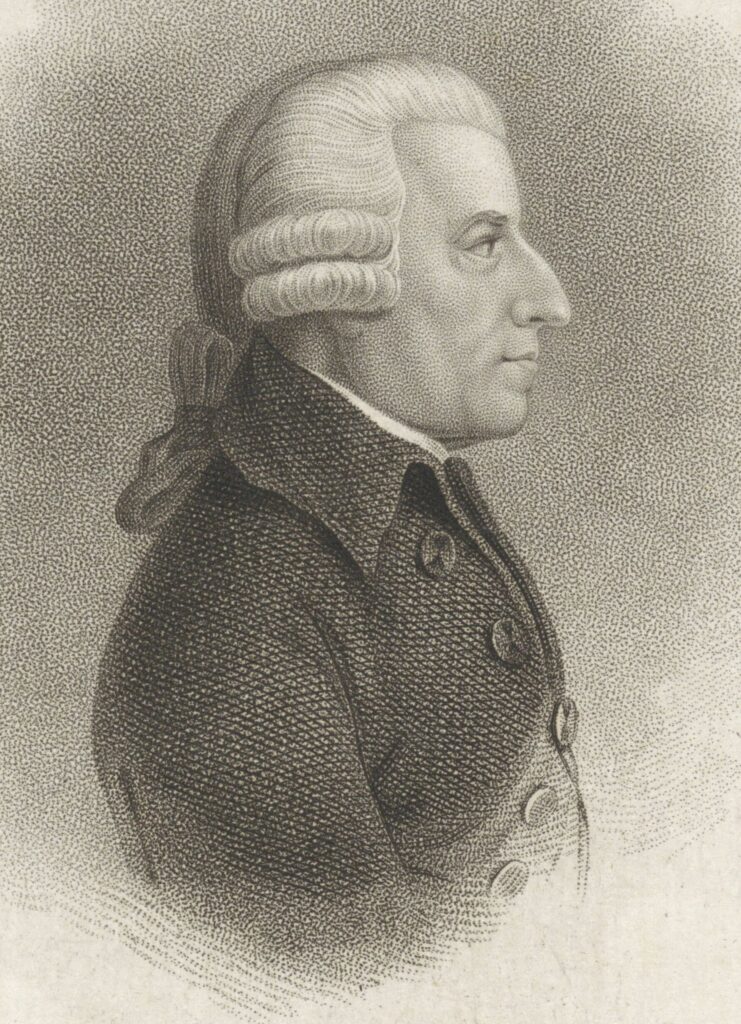

John Howard (1726 – 1790), today considered one of the founders of the penal reform movement in the Global North, was a devout Baptist, who was partly driven by religious belief, but was primarily concerned with improvement in conditions for prisoners. After being appointed Sheriff of Bedford, England in 1773, Howard decided to educate himself by visiting prisons throughout England and Europe, including a trip to Ireland in 1775. He made several suggestions for reforming prisons, including classification of prisoners, inspection by magistrates, regular visits from clergy, and paying jailers.[2] At the time, many prisoners had to pay for their own imprisonment, and could be prevented from being released until they paid discharge fees. The objective of imprisonment was, he believed, not just punishment, but reform and rehabilitation too. In keeping with his Christian ethos, Howard believed that hard labour, religious instruction and a regime of what today would be considered solitary confinement would be successful in reforming prisoners.[3] In 1774, Howard was instrumental in persuading the British parliament to pass two bills: one abolished discharge fees for prisoners, and the other established regulations for hygiene, such as regular cleaning and baths within prisons.[4]

In the 18th century, there was concern that deficiencies in inspection and oversight by local magistrates was partly responsible for shortcomings in prison conditions. In 1786, Jeremiah Fitzpatrick (1740 – 1810) was appointed a Prison Inspector for Ireland, and it became the first country in the Western World to have the post paid for by central government.[5] Fitzpatrick, “energetic, engaging, and of a philanthropic disposition,”[6] like many other critics of the prison was involved in various areas of social reform, around conditions in schools, convict ships, military hospitals and workhouses. In 1784, he published An essay on gaol abuses and six years later, Thoughts on penitentiaries. His obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine noted that he was “the zealous advocate of suffering Humanity in our Prisons and Hospitals, where his benevolence procured for him the appellation of a second Howard.”[7]

Although born in Germany, and on a sojourn from London, George Frederick Handel (1685 – 1759) chose Dublin for the first public performance of Messiah in 1742. With the lyrics predominantly based on Bible verses, Messiah raised £400 (equivalent to approximately £102,000 today) for charitable causes. The money was used for “the relief of the prisoners in several gaols,” Mercer’s Hospital and the charitable infirmary on the Inns Quay.[8] Some of the £400 was used to free 142 men from debtors’ prisons,[9] a fate Handel himself narrowly escaped as he was regularly in debt and had previously been declared bankrupt.

In the early 19th century, England “experienced an outpouring of social reform,” [10] with concerns about conditions in factories, hospitals, schools, and homelessness in urban areas. Inspired by her Quaker faith, Elizabeth Fry (1780 – 1845), the “leading female philanthropist of her generation,”[11] was active in many areas of social reform and charitable endeavours: to improve hospitals, asylums and workhouses, as well as campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade. In 1819, Fry opened a homeless shelter, and in 1824 established the Brighton District Visiting Society to provide help for the poor. She visited Ireland in 1823 to advocate for a female only prison, to be staffed with female officers.[12]

Fry had established the British Ladies’ Society for Promoting the Reformation of Female Prisoners in 1823. Under her guidance, “prison visiting became a fashionable pastime for respectable women.”[13] Elizabeth Fry used to conduct Scripture readings in prison, and such was its popularity, tickets were issued to visitors to have “the honour of being present when she read Scripture to prisoners.”[14] On her visit to Ireland in 1827 she chaired a meeting in Dublin of the newly formed Hibernian Ladies Society for Promoting the Improvement of Female Prisoners.[15] After campaigns for improvements in prison conditions by Fry and others, the Gaols Act 1823 was passed. Although it was only applicable in England and Wales, this Act hoped to create comparable and improved standards in prisons throughout the United Kingdom. It set out a system of classification: male and female prisoners were to be separated, with the latter to be guarded by female officers. It introduced regular visits to prisoners by chaplains. Regulations on health, hygiene, education and labour were introduced and alcohol was banned.[16]

Early Irish civil society organisations concerned with the treatment of prisoners included the Association for the Improvement of Prisons and of Prison Discipline in Ireland (AIPPD) which was established by Quakers and evangelical Anglicans in 1818.[17] Although only in existence for a brief period in the early 1800s, it influenced debates on the state of Irish prisons. The AIPPD campaigned for improvements in gaol design, education, employment and better conditions for female prisoners.[18]

Although more well known for her interest in education of girls and women, in particular the establishment of Alexandra College in Dublin 1866, the Quaker Anne Jellicoe (1823–1880) was concerned about the conditions of female prisoners.[19] She reported to a meeting of the National Association of Social Sciences in 1862 about her visit to Mountjoy Female Prison. She was positive about the influence of female staff and praised the ‘mark’ system, as the “prisoner is thus made aware how much her own welfare depends on her good conduct.” [20] She continued:

… by placing a premium on qualities totally different from those which led her into crime, the system gradually accustoms the prisoner to the loosening of the moral swathing bands by which she was at first restrained, and by infiltrating, as it were, habits of industry, self-denial, and self-respect, without which no woman can be reclaimed, places her in circumstances to secure herself from a relapse into crime. To so comprehensive an aim is added the elevating influence of religion.[21]

Although early advocates for the improvement of conditions were mainly engaged in charitable endeavours and sought legislative reform, they also believed that individual failing led to crime. While they expected improvements in the prison would provide better opportunities for reform, they also encouraged prisoners to heed the words of the prophet Isaiah, “stop doing wrong;

learn to do right” (Isaiah 1:16-17 NIV). However, others who were troubled about the plight of prisoners had no such concerns. It was primarily politics, but sometimes humanitarianism that inspired these campaigners.

“A different category to the ordinary”

Throughout the 19th and early 20th century, due to support for their cause, or prompted by humanitarian concerns, the plight of politically aligned prisoners attracted widespread political and public backing through amnesty campaigns, support networks, political movements and electoral contests.[22] In their refusal to be treated as criminals, prisoners convicted for physical force activities and their supporters demanded that they be treated differently to others convicted of “ordinary” crimes. Although rarely accepting of their penal regimes, by the 20th century, imprisonment was being used as “war by other means.”[23] Periodically, prisons became contested spaces as external struggles permeated the prison walls, and battles inside the prison had ripples, even tidal waves, outside.

Periodically, prisons became contested spaces as external struggles permeated the prison walls, and battles inside the prison had ripples, even tidal waves, outside.

One of the earliest support groups for politically aligned prisoners came soon after the foundation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood in 1858. Established in 1869, the focus of the Amnesty Association was the release of Fenian prisoners, but it also campaigned on wider social and political issues, and became the “largest political mobilization of mass popular opinion in Ireland since the 1840s.”[24] Nominally led by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Home Rule Party, it organised demonstrations with vast crowds, one in 1869 reportedly attracted 200,000 people.[25] Karl Marx expressed his support for the Amnesty Association. He criticised what he saw as the British government’s hypocrisy in their calling for the release of politically aligned prisoners in Italy, and yet they were unwilling to undertake such a course of action in Britain.[26] In 1870, in a critique of the British government’s treatment of Fenian prisoners, he mentioned Charles Kickham, John O’Leary and the particularly harsh regime under which Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa was held. He outlined the punitive conditions of their confinement:

The political prisoners are dragged from one prison to the next as if they were wild animals. They are forced to keep company with the vilest knaves; they are obliged to clean the pans used by these wretches, to wear the shirts and flannels which have previously been worn by these criminals, many of whom are suffering from the foulest diseases, and to wash in the same water. Before the arrival of the Fenians at Portland all the criminals were allowed to talk with their visitors. A visiting cage was installed for the Fenian prisoners. It consists of three compartments divided by partitions of thick iron bars; the jailer occupies the central compartment and the prisoner and his friends can only see each other through this double row of bars.[27]

The Amnesty Association’s campaign led to the release of many Fenian prisoners, with large welcoming home parties indicating popular support for their freedom.[28]

After being released half way through his 14-year sentence imposed in 1870, Michael Davitt (1846–1906) used his prison experience to campaign for penal reform. While incarcerated, he wrote Leaves from a Prison Diary; Or, Lectures to a ‘Solitary’ Audience, which chronicled prison life and his reflections on penal reform. He was subsequently a member of the Humanitarian League’s criminal law and prisons department, which “sought to humanize the conditions of prison life and to affirm that the true purpose of imprisonment was the reformation, not the mere punishment, of the offender.”[29] He gave evidence to the Departmental Committee on Prisons (chaired by Herbert Gladstone) which published a seminal report in 1895, stating “prison treatment should have as its primary and concurrent objects deterrence and reformation.”[30] It proposed, among other things, the abolition of hard labour machines, the reduction of time spent in separate confinement, and the development of education and training opportunities.[31] On his international tours, Davitt visited prisons in Australia and Honolulu. In 1898, as an MP, he became involved in the inspection of prisons, visiting institutions in Bedford, Birmingham and Bristol. Understandably, he showed particular interest in Portland and Dartmoor prisons, where he had previously been incarcerated.[32] Davitt was, however, “one of the very few, if not the only one, of the Fenians to show sympathy for the plight of ordinary criminals and to urge penal reform.”[33]

In the period after the 1916 Easter Rising, the Irish National Aid Association and Volunteer Dependents Fund (INAAVDF) gave financial and practical support to prisoners, ex-prisoners, and their dependents and made “a significant contribution to the transformation of public opinion.”[34] A mixture of popular and political support for their activities and humanitarian concerns for the people incarcerated led to the INAAVDF becoming “among the most effective instances of political welfarism in twentieth-century Ireland.”[35]

During the Civil War, despite the best efforts of the Free State government, the Women Prisoners’ Defence League (WPDL) led by Charlotte Despard (1844–1939) and Maud Gonne MacBride (1866–1953) highlighted the conditions and treatment of Republican prisoners. Established in August 1922 by the mothers, wives and sisters of Republican Prisoners, the WPDL used the “emerging rhetoric of international law and prisoner rights.”[36] In an attempt to embarrass the government, they petitioned international organisations including the Red Cross and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Despite many leaders of the new state having spent time in prison, few were interested in easing the plight of prisoners, especially as it would benefit their Civil War enemies. As Kevin O’Higgins informed the Dáil in November 1922, there “is not a member of this present Government who has not been in jail […] We have had the benefit of personal experience and personal study of these problems.”[37] However, he continued:

I think that everyone here would agree that we should aim at improvement and reform in the existing prison system. I think we would be unanimous in the view that a change and reform would be desirable. Personally, I can conceive nothing more brutalizing, and nothing more calculated to make a man rather a dangerous member of society, than the existing system. But one does not attempt sweeping reforms in a country situated as this country is at the moment.[38]

Penal reform would have to wait.[39] With only sporadic and peripheral interest in penal affairs throughout the early decades of the state, the outbreak of the conflict in Northern Ireland and the subsequent rise in the number of prisoners led to renewed interest in the plight of prisoners, north and south, and in Britain.

During the 1970s, Official IRA prisoners had a support group called Saoirse. Provisional IRA prisoners had the Relatives Action Committee.[40] However, after the abolition of special category status in Northern Ireland in March 1976, prisons became a major battleground. The Provisional IRA and its allies rejected the British government’s policy of criminalisation, demanded separation from other prisoners, and wanted to be treated as prisoners of war with all that entailed, both in the penal and political contexts.[41] Refusing to wear prison clothes led to the beginning of the ‘Blanket’ and ‘No Wash’ protests.[42]

Two years into their protest, Archbishop Tomás Ó Fiaich made a visit to Long Kesh Prison. He stated that the “authorities refused to admit that these prisoners were in a different category to the ordinary,”[43] and drew parallels with the penal experiences of the Fenians Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa and William O’Brien. He believed that “[n]o one could look on them as criminals. These boys are determined not to have criminal status imposed on them”.[44] The conflict in Long Kesh entered a new phase with the hunger strikes of 1980 and 1981, and the eventual death of ten prisoners.

Standing on an Anti-H-Block platform, and in support of political status, there was enough support among the voters of Fermanagh/South Tyrone to elect hunger striker Bobby Sands to Westminster in April 1981. Similarly, the Cavan/Monaghan and Louth constituencies returned hunger striker Kieran Doherty and Long Kesh prisoner Paddy Agnew respectively to the Dáil later that year, with hunger striker Joe McDonnell narrowly missing out on being elected in the Sligo/Leitrim constituency by 315 votes.[45]

Although politically aligned prisoners have tended to gain the most amount of political, popular and academic interest there were other groups providing support and solidarity which were more focussed on prisoners’ rights in general, and penal conditions for all prisoners.

“To preserve, protect and extend the rights of prisoners”

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, “ordinary” or “social” prisoners and their allies campaigned for improvements in conditions in Irish prisons. Although emerging during a wave of grassroots prisoner organisations and support networks that sprung to life across many jurisdictions, including Scandinavia, Great Britain, France and the United States, the issues “ordinary” prisoners raised were primarily local.[46]

The conditions in Irish prisons during the 1970s and 1980s were laid bare in an investigation by the Prison Study Group – made up of academics and members of civil society – in 1973. The vast majority of prisoners had to “slop out”;[47] they had to spend over 15 hours in their cell and there were limited productive out-of-cell activities. While there continued to be traditional prison industries, these were “menial” and did “not assist the prisoner’s chances of employment on release.”[48] It noted that prisoners still lived under the 1947 Prison Rules, an almost Victorian set of guidelines that were desperately in need of updating.

Discontent at the conditions of confinement, the standard of food, and the lack of recreational facilities prompted two sit-down protests in Portlaoise Prison over successive days in November 1972. These demonstrations were by ordinary or social prisoners and the Visiting Committee responded by imposing dietary punishment and loss of remission and privileges for ninety prisoners. Undeterred, the Portlaoise Prisoners Union (PPU) emerged because they felt “that the work done inside the prison was on a par with the work done on the outside.”[49] The prisoners’ demands included one third remission (under the 1947 Prison Rules, male prisoners were eligible for one quarter and female prisoners one third reduction of their sentence), a new parole board with an elected union member, improved visiting conditions, and educational facilities for all prisoners with special emphasis for those with literacy difficulties. The PPU wanted a skilled trades programme to be introduced and the current wage level of 10p a day to be increased to £10 a week. They demanded an end to censorship of mail, books, and newspapers and the immediate abolition of dietary punishment. Finally, the PPU called for reform of the Visiting Committee, because they had little faith in its impartiality. The PPU spread, eventually calling itself the Prisoners Union. After the initial surge of activity, sporadic demonstrations occurred throughout the 1970s, usually sit-down strikes, refusal to attend work, and periodically, hunger strikes.[50]

In 1973 former prisoners who had been involved in the PPU and others interested in penal reform, called a public meeting to generate public support “to preserve, protect and extend the rights of prisoners, and seek the implementation of the 11 demands of the Portlaoise Prisoners Union.”[51] At this meeting, the Prisoners’ Rights Organisation (PRO) was established. It campaigned to improve what were generally considered substandard conditions in Irish prisons. It called for the “immediate implementation of a comprehensive system of penal reform in Irish jails.”[52] It had an extensive list of demands, ranging from improvements in the provision of education and vocational training, to extended recreation facilities, and improved visiting conditions, with more regular visits. The PRO, echoing the demands of the Prisoners Union, insisted that prisoners should have the right to establish a union, with trade union rates of pay for prison work. They sought the right to vote in local and general elections and to join political parties.

The activities of PRO were broadly grouped into three categories: campaigning and activism, research into the penal system, and practical initiatives. Widening its remit beyond a critique of the prison system, members of the PRO became involved in issues such as campaigning against the new Criminal Justice Act 1984; they opposed the re-opening of Loughan House as a juvenile detention centre, condemning it as a children’s prison, and supported the abolition of the death penalty. The PRO published the Jail Journal, which they claimed reached a circulation of up to 3,000 copies.[53] The organisation petered out in the mid-1980s. With the publication of the Whitaker Report, in 1985, it believed that had achieved its goal of highlighting the conditions in Irish prisons. Many of its earliest leaders went on to prominent positions in Irish life.[54]

“An end to structural injustice in Irish society”

Contemporary organisations in what could be loosely called the charity sector tend to take a different approach to their charitable forebears. Social justice rather than charity alone informs their practice. Broadly categorised into campaigning and advocacy, and service provision, there is some cross-over. As its names suggests the Irish Council for Prisoners Overseas, provides information and support to Irish prisoners and their families outside Ireland. Established in 1985 by the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference amid concerns about the treatment of Irish prisoners in British jails, it continues to deal with the unique challenges of Irish prisoners overseas facing “significant difficulties, including dealing with an unfamiliar legal system, discrimination and language barriers.”[55] Established in 1994, the Irish Penal Reform Trust campaigns for “a national penal policy which is just, humane, evidence-led, and uses prison as a last resort.”[56] The Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice locates the prison and the plight of prisoners in a structural context. It argues that “[o]ur prisons function as warehouses filled with people on the periphery of and rejected by society. […] we can see that people in prison are among the most marginalised and vulnerable in the country”. It believes that penal reform is tied in with “an end to structural injustice in Irish society.”[57]

There are various organisations that continue the tradition of prisoner representation of the 1960s and 1970s, focussed more on solidarity and allyship amongst, and with, prisoners. They argue that people with experience of imprisonment should mould and lead the programme for penal change, with the support of allies outside. What distinguishes them is not just the searing critique of the penal system, but their rejection of penal reform campaigns and charitable endeavours, which they argue legitimises the existence of prisons by softening the pain of confinement.[58] One of the oldest prisoner solidarity movements is the Anarchist Black Cross (ABC) which had its genesis during the Tsarist Russian Empire supporting political prisoners and their families.[59] It has mainly an online presence here through Anarchist Black Cross Ireland. It organises an annual Week of Action with Anarchist Prisoners, a Radical Book fair and solidarity actions.[60] ABC has co-operated with the Incarcerated Workers Organising Committee (IWOC), a prisoner-led section of the International Workers of the World (IWW). Almost unique among trade unions internationally, article II of the IWW constitution explicitly welcomes prisoners, with law enforcement and prison officers barred.[61]

Established in the US, and now with branches worldwide, the IWOC aims to “support prisoners to organise and fight back against prison slavery and the prison system itself.”[62] Prisoners who work, IWOC argues, “‘have no rights to organise, no contracts, no pensions, no right to choose what they do.”[63] It contends that there is a responsibility on wider social movements to support prisoners in their individual and collective struggles and seeks to “build class solidarity amongst members of the working class by connecting the struggle of people in prison, jails, and immigrant and juvenile detention centres to workers struggles locally and worldwide.”[64] IWOC Ireland has an active and energetic online presence, with its own zine for prison abolition, Bulldozer. It is involved in various campaigns around education, health and employment, and supporting individual prisoners and their families.[65] With an emphasis on prisoners and ex-prisoners leading movements for penal change, ABC and IWOC question the use of imprisonment in the context of the struggle for social and political transformation.

Conclusion

With a focus primarily on Irish prisons and prisoners, this essay has examined campaigns for improvement in prison conditions and expressions of support for the plight of prisoners through philanthropy, charitable endeavours, allyship and solidarity. Some the concerns of early reformers are still with us today: overcrowding, prison regimes, deficiencies in monitoring and accountability, access to education and programmes, and support for people with mental health issues.

While some of the proposals from early critics may seem archaic, quaint, or at times problematic to today’s reformers, they were driven by a desire for remodelled prisons, which they believed would provide the space to allow prisoners to repent and reform. Using their position as pillars of the establishment many advocated for legislative changes to improve penal conditions, including modifications in regime, classification of prisoners, and government inspection. Although campaigns highlighting the plight of prisoners have rarely been mass movements, the conditions for politically motivated prisoners were one of the exceptions. Based on a mixture of political and humanitarian principles, as the sight of prisoners during the ‘Blanket’ and ‘No Wash’ protest was beamed to the world outside, the H-Block campaign captured the imagination, and attracted a wave of support from wider society beyond traditional campaigners.

Although there have been a number of movements for “ordinary” prisoners since the 1960s and 1970s few have gained the level of support in Ireland or internationally, or have had as much penal or political impact as prisoners’ rights organisations of the 1970s.[66] Today’s charitable bodies and prisoner solidarity organisations are not mass movements. However, they recognise that punishment is not distributed equally and prisons across the globe house some of the most marginalised sections of society. While no longer focussed on saving souls, contemporary charitable organisations tend to highlight a social justice agenda rather than the philanthropy of earlier times. The ABC and IWOC provide solidarity and allyship, give voice to prisoners, and provide a powerful critique of the penal system.

While no longer focussed on saving souls, contemporary charitable organisations tend to highlight a social justice agenda rather than the philanthropy of earlier times. The ABC and IWOC provide solidarity and allyship, give voice to prisoners, and provide a powerful critique of the penal system.

Almost 20 years ago, Cavadino and Dignan wrote: “[a]s icy winds of punitive law and order ideology seemingly sweep the globe, we need to hold fast to the recognition that things can be done differently to the dictates of the current gurus of penal fashion.”[67] As with all fashion, penal modes change. When the icy winds meet the warm glow of compassion and solidarity, it is important to bear in mind that while advocates for punitive approaches are not new, there is a long and rich tradition of resistance to this ideology. As this essay has shown there were, and are, many who still believe that things can, and indeed should be done differently.

Dr Cormac Behan is a lecturer in criminology at Maynooth University School of Law and Criminology. He is the author (with Dr Abigail Stark) of Prisons and Imprisonment: An Introduction (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023).

[1] Muriel Schmid, ‘“The Eye of God”: Religious Beliefs and Punishment in Early Nineteenth-Century Prison Reform’, Theology Today 59, no. 4 (2003): 554.

[2] Robert Alan Cooper, ‘Ideas and Their Execution: English Prison Reform’, Eighteenth Century Studies 10, no. 1 (1976): 73–93.

[3] George Fisher, ‘The Birth of the Prison Retold’, The Yale Law Journal 104, no. 6 (1995): 1237.

[4] Cooper, ‘Ideas and Their Execution’.

[5] Richard J. Butler, ‘Rethinking the Origins of the British Prisons Act of 1835: Ireland and the Development of Central-Government Prison Inspection, 1820–1835’, The Historical Journal 59, no. 3 (2016): 727.

[6] C. J. Woods, ‘Fitzpatrick, Sir Jeremiah’, Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009, https://www.dib.ie/biography/fitzpatrick-sir-jeremiah-a3236.

[7] ‘Obituary, with Anecdotes, of Remarkable Persons’, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Jan-Jun 1810, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433081674461&seq=203&q1=Howard.

[8] Paul Collins, ‘Handel, George Frederick’, Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009, https://www.dib.ie/biography/handel-george-frederick-a3777.

[9] Donald Burrows, ‘In Handel’s Shadow: Performances of Messiah in Dublin during the 1740s’, The Musical Times 161, no. 1950 (2020): 9–20.

[10] Leonard H. Roberts, ‘John Howard, England’s Great Prison Reformer: His Glimpse Into Hell’, Journal of Correctional Education 36, no. 4 (1985): 136.

[11] Robert Alan Cooper, ‘Jeremy Bentham, Elizabeth Fry, and English Prison Reform’, Journal of the History of Ideas 42, no. 4 (1981): 682.

[12] Anne Jellicoe, Visit to the Female Convict Prison at Mountjoy, Dublin. Transactions of the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science to the Social Science, London Meeting 1862 (London: John W. Parker, Son, & Bourn, 1863), 437.

[13] Cooper, ‘Jeremy Bentham, Elizabeth Fry, and English Prison Reform’, 685.

[14] Cooper, 684.

[15] Joan Kavanagh, ‘’From Vice to Virtue, from Idleness to Industry, from Profaneness to Practical Religion’ Grangegorman Penitentiary’, Royal Irish Academy, 6 March 2023, https://www.ria.ie/blog/from-vice-to-virtue-from-idleness-to-industry-from-profaneness-to-practical-religion-grangegorman-penitentiary/.

[16] Harry Potter, Shades of the Prison House: A History of Incarceration in the British Isles (Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2019), 193.

[17] Butler, ‘Rethinking the Origins of the British Prisons Act of 1835’.

[18] Butler, 730.

[19] Susan M. Parkes, ‘Jellicoe, Anne’, Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009, https://www.dib.ie/biography/jellicoe-anne-a4268.

[20] Jellicoe, Visit to Female Convict at Mountjoy, 438-9. The ‘mark’ system was used in Ireland under William Crofton (1815-1897) who was Chairman of the Directors of Convict Prisons. Originally developed by Alexander Maconochie in the 1840s, Crofton’s three stage system involved ‘marks’ being earned for good conduct and lost for disobedience and rule-breaking. Prisoners became eligible for release when they earned the required number of ‘marks’. See Gerry McNally, ‘James P. Organ, the “Irish System” and the Origins of Parole’, Irish Probation Journal 16 (2019): 42–59.

[21] Jellicoe, Visit to the Female Convict Prison at Mountjoy, 442.

[22] See Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1848-1922: Theatres of War (London: Routledge, 2003); Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1920-1962: Pilgrimage of Desolation (London: Routledge, 2013); Seán McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1960-2000: Braiding Rage and Sorrow (London: Routledge, 2021).

[23] McConville, Irish Political Prisoners, 1848-1922, 509.

[24] Oliver Rafferty, The Church, the State and the Fenian Threat 1861–75 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999), 121.

[25] Owen McGee, ‘Nolan, John (“Amnesty Nolan”)’, Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009, https://www.dib.ie/biography/nolan-john-amnesty-nolan-a6220.

[26] Karl Marx, ‘On the Policy of the British Government with Respect to the Irish Prisoners’, in Marx & Engels Collected Works, 2nd Russian, vol. 21, 50 vols (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1960), 407. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/iwma/documents/1869/irish-prisoners-speech.htm.

[27] Karl Marx, ‘The English Government and the Fenian Prisoners’, in Marx and Engels on Ireland (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1971), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1870/02/21.htm.

[28] Donal McCartney, ‘The Church and the Fenians’, University Review 4, no. 3 (1967): 213.

[29] Victor Bailey, ‘English Prisons, Penal Culture, and the Abatement of Imprisonment, 1895–1922’, Journal of British Studies 36, no. 3 (1997): 306.

[30] ‘Report from the Departmental Committee on Prisons and Minutes of Evidence (Gladstone Report)’ (London: Departmental Committee on Prisons, 1895), 18.

[31] ‘Report from the Departmental Committee on Prisons and Minutes of Evidence (Gladstone Report)’; See also, Martyn Housden, ‘Oscar Wilde’s Imprisonment and an Early Idea of “Banal Evil” ’ or ’Two “Wasps” in the System. How Reverend W.D. Morrison and Oscar Wilde Challenged Penal Policy in Late Victorian England’, Forum Historiae Iuris, 2006, https://forhistiur.net/2006-10-housden/.

[32] Laurence Marley, Michael Davitt: Freelance Radical and Frondeur (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2010), 208.

[33] Leon Radzinowicz and Roger Hood, ‘The Status of Political Prisoner in England: The Struggle for Recognition’, Virginia Law Review 65, no. 8 (1979): 1454.

[34] Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid, ‘The Irish National Aid Association and the Radicalization of Public Opinion in Ireland, 1916–1918’, The Historical Journal 55, no. 3 (2012): 706. See also William Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[35] Nic Dháibhéid, ‘The Irish National Aid Association and the Radicalization of Public Opinion in Ireland, 1916–1918’, 729.

[36] Lia Brazil, ‘Women Prisoners’ Defence League’, Mná 100, 2022, https://www.mna100.ie/centenary-moments/women-prisoners-defence-league/.

[37] Kevin O’Higgins TD, ‘General Prisons Board – Dáil Éireann (3rd Dáil)’, Houses of the Oireachtas, 28 November 1922, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/debates/debate/dail/1922-11-28/27.

[38] O’Higgins TD.

[39] Cormac Behan, Citizen Convicts: Prisoners, Politics and the Vote (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014).

[40] ‘Political and Pressure Groups’, Magill Magazine, 2 October 1977, https://magill.ie/archive/political-and-pressure-groups.

[41] See Kieran McEvoy, Paramilitary Imprisonment in Northern Ireland: Resistance, Management, and Release (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

[42] David Beresford, Ten Men Dead: The Story of the 1981 Hunger Strike (London: Grafton, 1987).

[43] Archbishop Tomas O’Fiaich, cited in David McKittrick, ‘Archbishop Compares H-Block to Calcutta Slums’’, Irish Times, 2 August 1978, sec. 1 & 5.

[44] Archbishop Tomas O’Fiaich, cited in McKittrick.

[45] Beresford, Ten Men Dead.

[46] For Scandinavia, see Thomas Mathiesen, The Politics of Abolition (London: Martin Robertson, 1974); for Republic of Ireland, see Cormac Behan, ‘“We Are All Convicted Criminals”? Prisoners, Protest and Penal Politics in the Republic of Ireland’, Journal of Social History 52, no. 1 (2018): 501–26; for Great Britain, see Cormac Behan, ‘The Summer of Discontent: The British Prisoners Strike of 1972’, in The Emerald International Handbook of Activist Criminology, ed. Victoria Canning, Greg Martin, and Steve Tombs (London: Emerald Publishing, 2023); for France, see Michael Welch, ‘Counterveillance: How Foucault and the Groupe d’Information Sur Les Prisons Reversed the Optics’, Theoretical Criminology 15, no. 3 (2011): 301–13; for United States, see C. Ronald Huff, ‘Unionization behind the Walls’, Criminology 12, no. 2 (1974): 175–93.

[47] As a consequence of having no flushing toilet, slopping out is when prisoners empty the containers they use as toilets during the night in the cells where they sleep.

[48] Prison Study Group, ‘An Examination of the Irish Penal System’ (Dublin: Prison Study Group, 1973), 89.

[49] Prisoners’ Rights Organisation, Jail Journal, 1, no.1, (n.d.), https://www.leftarchive.ie/publication/2503/.

[50] Behan, Prisoners, Protests and Penal Politics’.

[51] John Kearns, ‘Prisoners’ Rights’, Irish Press, 7 July 1973.

[52] ‘Jail Journal’ 1, no. 1 (n.d.), See also Oisín Wall, ‘“Embarrassing the State”: The “Ordinary” Prisoner Rights Movement in Ireland, 1972–6’, Journal of Contemporary History 55, no. 2 (2019): 388–410.

[53] Prisoners’ Rights Organisation, ‘Jail Journal’ 1, no. 12 (n.d.), https://www.leftarchive.ie/publication/2503/.

[54] Cormac Behan, ‘“Nothing to Say”? Prisoners and the Penal Past’, in Histories of Punishment and Social Control in Ireland: Perspectives from a Periphery, ed. Lynsey Black, Louise Brangan, and Deirdre Healy (London: Emerald Publishing, 2022), 250.

[55] ‘About Us’, Irish Council for Prisoners Overseas, accessed 7 August 2024, https://www.icpo.ie/about-us/.

[56] ‘What We Do’, Irish Penal Reform Trust, accessed 7 August 2024, https://www.iprt.ie/what-we-do/.

[57] ‘Penal Policy’, Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, accessed 7 August 2024, https://www.jcfj.ie/what-we-do/penal-policy/.

[58] ‘Bristol Anarchist Black Cross, Prisoner Solidarity in the UK’, Journal of Prisoners on Prisons 20, no. 2 (2011): 173–75.

[59] Colleen Hackett, ‘Justice through Defiance: Political Prisoner Support Work and Infrastructures of Resistance’, Contemporary Justice Review 18, no. 1 (2015): 68–75; Dana M. Williams, ‘Contemporary Anarchist and Anarchistic Movements’, Sociology Compass 12, no. 6 (2018): 1–17.

[60] ‘Anarchist Black Cross Ireland’, Anarchist Federation, accessed 7 August 2024, https://www.anarchistfederation.net/author/anarchist-black-cross-ireland/.

[61] ‘Constitution of the Industrial Workers of the World’, Industrial Workers of the World, accessed 7 August 2024, https://www.iww.org/constitution/.

[62] ‘About’, Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee, accessed 7 August 2024, https://incarceratedworkers.org/about.

[63] ‘About’, Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.

[64] ‘About’, Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee.

[65] IWOC, Bulldozer. https://www.onebigunion.ie/bulldozer.

[66] Joel Charbit, ‘Mobilisation of Prisoners, Trade Union Strategy (Interview)’, les Utopiques, 2018, https://www.lesutopiques.org/mobilisations-de-prisonnier%c2%b7es-strategie-syndicale-entretien-avec-joel-charbit/.

[67] Michael Cavadino and James Dignan, Penal Systems: A Comparative Approach (London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2006), 4.