Peter McVerry SJ, Eoin Carroll and Margaret Burns

Homelessness

The Continuing Rise in Homelessness

The most disturbing aspect of the current housing crisis is, of course, the extent to which individuals and families are experiencing homelessness.

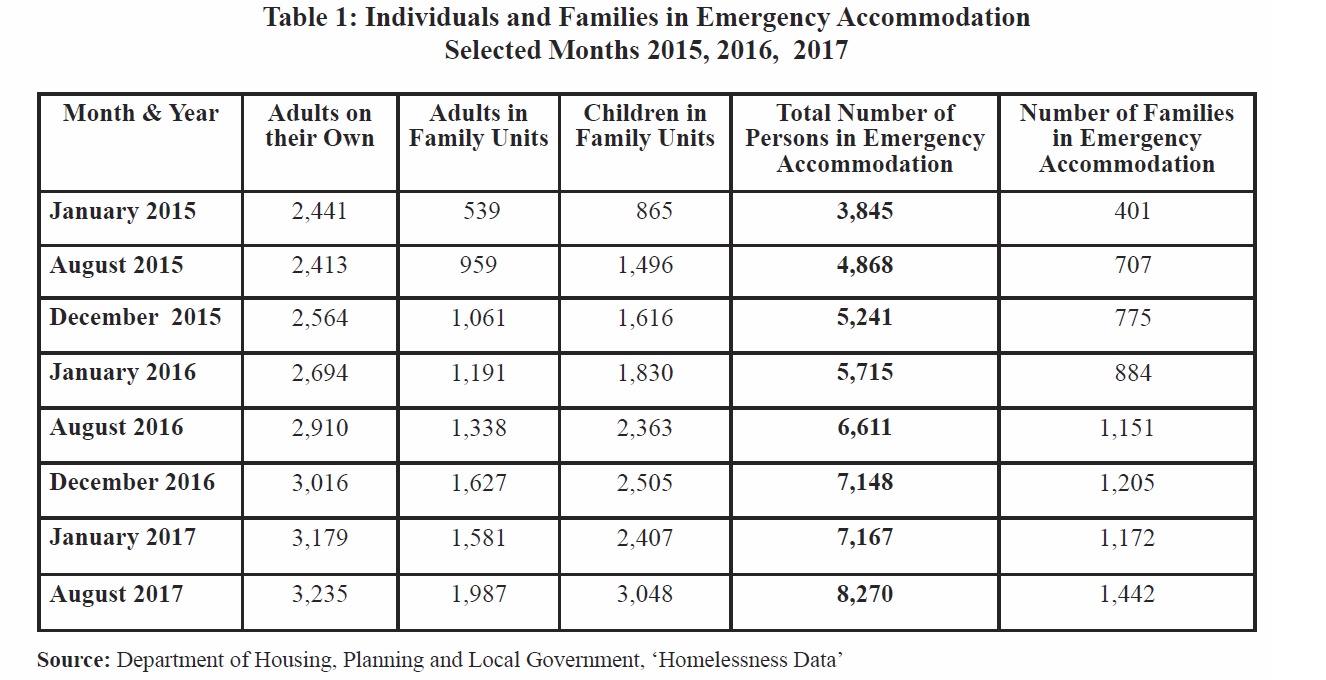

While homelessness has been rising since at least 2013 there has been a particularly marked increase since 2015. As indicated by Table 1 below, the total number of people living in emergency accommodation more than doubled in the period January 2015 to August 2017 (rising from 3,845 to 8,270). The number of families in such accommodation more than tripled (rising from 401 in January 2015 to 1,442 in August 2017), as did the number of children (increasing from 865 to 3,048). One person in three now living in emergency accommodation in Ireland is a child. There has also been a 32 per cent increase in the number of adults on their own in emergency accommodation (up from 2,441 in January 2015 to 3,235 in August 2017).1

In addition to these official figures, there are many people who are in fact without a home but are not registered as such. These include individuals and families who are ‘doubling up’ with family members or friends, and those who are ‘couch-surfing’. They also include those who have left their homes because of domestic violence and have gone into a women’s refuge but who may not be considered by local authorities as being ‘without a home’ and so may have no option but to continue living in the refuge beyond the period for which such accommodation is intended.2

Furthermore, the official figures on homelessness do not include individuals and families who have been granted refugee status, or some other form of protection, but cannot find accommodation and so remain in Direct Provision. At the end of December 2016, there were approximately 450 people in this situation.3

The great majority of families who are homeless are in the Dublin Region: 1,146 out of the overall total of 1,442 in August 2017. The August figure, in fact, represents a decrease of 32 on that for July. This decrease reflects increased exits by families out of homelessness – obviously a welcome development. However, even as this has been occurring the inflow of new families into homelessness continues. In each of the first six months of 2017, an average of 75 families became homeless in Dublin for the first time.4 In July, the number of families newly homeless rose to 99;5 in August the number was 102.6

While there is an understandable focus on the family homelessness crisis in the Dublin region, the significant increase in the incidence of such homelessness in other regions of the country often tends to be overlooked (for example, this issue was not considered in Rebuilding Ireland, the Government’s Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, published in July 2016).7 In the regions other than Dublin, the total number of families in emergency accommodation increased seven-fold between January 2015 and August 2017 (rising from 42 to 296) and the number of children involved rose nearly eight times (rising from 85 to 669).8 Whereas 10.5 per cent of families and 10 per cent of children in emergency accommodation in January 2015 were in regions outside Dublin, by August 2017 these figures had increased to 20.5 per cent and 22 per cent respectively.9

The parts of the country which in the past have not had a significant incidence of homelessness, and especially family homelessness, may have limited services available to respond to the needs of those now presenting as homeless. The situation in these areas certainly merits specific attention in national plans to address homelessness.

The continuing increase in the number of people who are homeless is occurring despite the fact that additional services have been put in place to assist people in danger of becoming homeless (for example, the Threshold Tenancy Protection Service) and to enable people to exit homelessness. The Third Quarterly Progress Report on the implementation of Rebuilding Ireland (issued in May 2017) pointed out that, during 2016, there had been ‘just over 3,000 sustainable exits from homelessness into independent tenancies’;10 the Department of Housing’s Homelessness Report August 2017 indicated that, in the first six months of the year, 1,260 tenancies had been created to enable people exit homelessness.11

Clearly, while the various initiatives to prevent homelessness and assist people move out of homelessness are important responses, deep structural problems within the Irish housing system are continuing to generate homelessness at an alarming rate.

Emergency Accommodation for Families

As the crisis in family homelessness has deepened so has concern about the impact on families of living in emergency accommodation, especially for a prolonged period. People with experience of living in such accommodation, media reports, NGOs working in the area of homelessness, and research findings have all highlighted the severe difficulties associated with living in hotels and B&Bs. These include the lack of adequate space and privacy, the absence of cooking facilities and the barriers to ensuring adequate nutrition, the absence of appropriate spaces for children to play or study, the lengthy journeys many children have to make in order to remain in the school they had been attending – and the physical and emotional strain which these and other difficulties place on both parents and children.12

Rebuilding Ireland recognised the unsuitability of hotels and B&Bs as a form of emergency accommodation for families. The Plan announced a number of additional supports and services to ameliorate some of the day-to-day difficulties facing families in this situation. Its key commitment, however, was ‘to move the existing group of families out of these hotel arrangements as quickly as possible, and to limit the extent to which such accommodation has to be used for new presentations. Our aim is that by mid-2017, hotels will only be used for emergency accommodation in very limited circumstances.’13

In June 2017, the Minster for Housing, Eoghan Murphy TD, announced that while there had been significant progress in enabling families to move out of commercial hotels and B&Bs, and in helping families to avoid having to go into such accommodation, the target of minimal use of hotels and B&Bs could not be met by mid-summer 2017 – but that this would continue to be the objective of policy.14

The central issue here is not, however, a ‘slippage’ in the timeline for moving away from using these forms of emergency accommodation but rather the fact that in the months following the publication of Rebuilding Ireland it became apparent that the means of meeting that goal now included the development of a new type of emergency accommodation – ‘family hubs’. This had not been signalled in Rebuilding Ireland; rather, that document clearly implied that the target would be met through a range of measures that would enable families to gain access to housing in the community.15

By the end of June 2017, an official statement indicated that fifteen family hubs had been or were being developed, with accommodation for around 600 families, at an estimated cost of €25 million. This provision, the Statement said, would be augmented by a further €10 million so as to accommodate at least another 200 families.16

On 8 September 2017, the Minister for Housing announced that, arising from the first phase of the review being undertaken of Rebuilding Ireland, and following a Housing Summit convened by the Minister and held on that day, extra measures to address homelessness would include the allocation of a further €10 million for family hubs.17 This presumably will mean provision for around 200 families and bring the total number of places in this form of accommodation to 1,000.

Family hubs, which are to be operated both by voluntary organisations and private providers and will include former commercial hotels which have been repurposed, are presented as offering increased living space and more appropriate accommodation than hotels and B&Bs, providing better facilities and greater stability, as well as access to support services. However, concerns have been expressed that there is no assurance there will be consistency in the standards of accommodation and availability of facilities and services across different centres.

Moreover, family hubs are ultimately institutional living arrangements, in which parents and children have to share living space with people who are strangers to them. Concerns have been expressed that the structures and regulations considered necessary for the operation of these centres, and for the assurance of child protection, will impact on normal interactions within and between families, and impinge on family privacy and autonomy and on the exercise of parental roles.18

Furthermore, the authors of a study on family hubs have highlighted the danger that this newer form of emergency accommodation may become ‘an entrenched’ feature of Irish society’s response to family homelessness.19 They have argued that there should be a ‘sunset clause on the existence of family hubs as a policy option’, with all such centres closing by December 2019.20

The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission has stated that family hubs ‘are only appropriate for short-term emergency accommodation’. It has recommended that the legislation governing the provision of emergency accommodation (Section 10, Housing Act, 1988) be amended to place a limit on the length of time a family will spend in emergency accommodation of any kind, suggesting that this should be no more than three months.21 At present, it would appear that large numbers of families are spending far longer than this in emergency accommodation.22

Rapid Build Housing

One of the reasons for the failure to meet the commitment to move families experiencing homelessness out of commercial hotels and B&Bs, and for the resort to new forms of emergency accommodation, has been the slow implementation of the plan to provide Rapid Build homes for families who are homeless in the Dublin area.

The Rapid Build programme was originally announced in October 2015 with the objective of providing 500 units; in Rebuilding Ireland the target was increased to 1,500 units, with 200 units to be completed by the end of 2016, a further 800 in 2017, and 500 in 2018.

However, by the end of 2016, only 22 rapid build homes had been completed and occupied. The Third Quarterly Progress Report on Rebuilding Ireland stated that 350 units ‘were advancing through various stages of delivery, including construction’, but indicated that just 175 would be completed by the end of 2017.23 This suggests that two years after the Rapid Build programme was first announced the total number of completions will be just under 200.

Emergency Accommodation for Individuals

Rebuilding Ireland included a commitment to ensuring that ‘there are sufficient emergency beds available in our urban centres for homeless individuals’.24 During winter 2016, over 200 additional beds were made available in Dublin. For a time, this extra provision seemed to make a real difference in terms of people being able to access emergency accommodation, but then, as the flow into homelessness continued unabated, the number of people forced to sleep on the street began to grow once more. The Dublin Region Homeless Executive ‘Rough Sleeping Count’ carried out on 4 April 2017 showed 161 people recorded as sleeping rough in the Region – a figure that was more than 50 per cent higher than the number recorded in April 2016 (102) and in April 2015 (105).25

In the Press Statement issued on 8 September 2017, following that day’s Housing Summit, the Minister for Housing announced that an additional 200 emergency beds for individuals would be provided in Dublin by the end of December 2017, with 100 of these being available by the end of October.26

An issue which is all too seldom discussed, and which was not mentioned in Rebuilding Ireland, is the quality of emergency accommodation. Very often such provision is dormitory-type accommodation where bullying, intimidation, drug misuse and violence are frequent occurrences. Young people just out of care may be sharing accommodation with people who have committed criminal offences; people who have never touched a drug may be sharing with active drug users who are injecting heroin or smoking crack cocaine during the night in front of them; people who have completed a drug treatment programme, and are now in recovery, may be sharing a room with drug dealers who threaten them if they refuse to buy drugs from them; people who were sexually abused as children are forced to sleep in a room full of strangers.

Until there is a focus on significant improvements in the quality and security of the emergency accommodation provided, many people will continue to sleep rough, as they feel safer by doing so. Unfortunately, this rough-sleeping group includes the most vulnerable among those who are without a home.

A positive development is that a ‘National Quality Standards Framework’ for homeless services is being prepared by the Dublin Region Homeless Executive; the stated aim was that this would be rolled out during 2017. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission has said that, once the Framework is implemented, ‘homeless services should be subject to regular inspection by an independent inspection body’.27

Just as the time a family has to spend in emergency accommodation should be limited to a defined period (as the Human Rights Commission recommends), so also there should be a limit to the length of time an individual has to avail of emergency accommodation before long-term housing is provided.

Housing First Programme

In line with the official commitment to a ‘housing-led’ approach to addressing homelessness, as set out in the Homelessness Policy Statement of 2013,28 the Housing First programme in Dublin aims to enable people who have been homeless for a long time, and who may have multiple needs, to obtain permanent secure accommodation, with the assistance of a support team to help them address their needs. The support team may include a social worker, addiction worker, psychiatrist, mental health professional, a nurse and other appropriate professionals. It is therefore a very expensive programme. While the tenancy does not require the person who had been homeless to address the personal issues affecting their lives, the support is there if wanted. The conditions of the tenancy under Housing First are the same as those for any other tenant and include paying their rent and refraining from anti-social behaviour. This programme has been extremely successful in enabling people, even those who have been a long time without a home, to move out of homelessness.

Rebuilding Ireland proposed the trebling of the target for the provision of tenancies under the Housing First programme in Dublin, from 100 units to 300 units in 2017. However, reaching that target in 2017 is a challenging task: the Progress Report on Rebuilding Ireland published in May indicated that in the first quarter of the year just 62 such tenancies had been put in place.29 The essential requirement of a Housing First programme is, of course, access to housing. In current circumstances, a major difficulty is the extent to which the programme must rely on securing tenancies in the private rental sector, where units in the relevant price range are extremely difficult to find.

The Press Statement of the Minister for Housing on 8 September 2017 included the announcement that: ‘Local Authorities will coordinate with Housing Bodies to build more one-bed homes for individuals and those under Housing First programmes.’30 This is obviously a welcome development; however, no indication was given as to how many additional new units of this type are envisaged. The Press Statement also included a commitment to extend Housing First to the other main urban areas, with a target of 100 places to be provided.

Young People

While Rebuilding Ireland notes the vulnerability of young people leaving care to becoming homeless, it does not address more generally the particular issues facing young people who are homeless, or are in danger of becoming so. Other official policy statements, for example, The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People,31 acknowledge the specific difficulties facing this group, the challenges of responding appropriately, and the need for a distinct approach. The Irish Coalition to End Youth Homelessness recommends that a separate sub-strategy within Rebuilding Ireland should be developed for young people in the 18–25 age category who are homeless.32

Social Housing

A Failure of Policy

Ultimately, the homelessness crisis reflects the failure of Ireland’s social housing policy over the past quarter century to ensure an adequate supply of appropriate and secure accommodation for the various types of households who may need social housing.

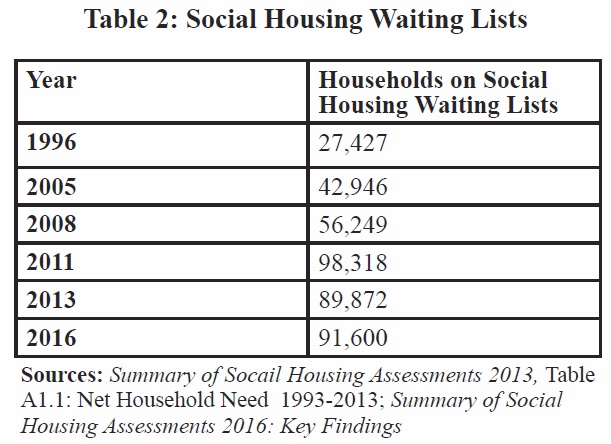

A broader indicator of the failings of that policy is the marked rise in the number of households waiting for social housing. Between 1996 and 2008 – the period in which Ireland was experiencing its fastest ever rate of economic growth – that number more than doubled, rising from 27,427 to 56,249 (see Table 2).

The 2016 assessments of social housing need revealed that there were 91,600 households on social housing waiting lists (an increase of 63 per cent on the 2008 figure); these households were comprised of 210,000 people, including 84,000 children.33

The waiting list figure for 2016 was only 1,728 (or 1.9 per cent) greater than that for 2013. Understandably, questions have been raised about this, given the growing problem of housing availability and affordability, and the marked rise in homelessness since 2013. One factor influencing the 2016 statistics on waiting lists is that, although some households receiving Rent Supplement are included, those receiving HAP (Housing Assistance Payment) are not.

In 2016, over 54,300 households (59 per cent of the total) had been on the waiting list for longer than three years and 19,383 (21 per cent) had been on the list for more than seven years. These figures indicate a significant increase in the length of time people are waiting for social housing, even since 2013: in that year, 45 per cent had been waiting more than three years, and 8.9 per cent seven years or longer.34 In 2005, less than a quarter of households had been waiting more than three years for social housing.35

Core Features of Policy

Social housing policy in Ireland over the past quarter century has been characterised by two distinct but closely interrelated features – a low level of provision of new social housing units relative to need, and an increasing reliance on the supplementation of rents in the private rental sector as a way of responding to social housing need.

Social housing provision

From 1973 to 1986, on average, 6,400 houses were built each year by local authorities (the total number for this period was 90,000).36 Construction of such housing then fell sharply, and even as house building in Ireland increased significantly from 1994 onwards, social housing provision grew only slowly and did not show substantial increases until around 2002.37 From then until 2008 there was significant additional provision by local authorities and voluntary housing bodies, both through ‘new build’ and the purchase of housing from the private market,38 though this was still not sufficient to meet social housing requirements – as the rise in the number of households on waiting lists indicates.

With the recession came sharp decreases in budget allocations for social housing; the consequences of this took some time to become apparent but by 2010 total completions and acquisitions by local authorities and voluntary bodies had fallen to 2,931 (from 7,588 in 2008 – a decline of 61 per cent). By 2012, there had been a further decline to 1,391 (around one-fifth of the provision in 2008). In 2015, only 645 new social housing units were provided, with local authorities supplying just 75.39 In other words, by 2015, output of social housing had fallen to less than one-tenth of what it had been in 2008. It has been calculated that if, over the seven-year period 2010 to 2016, new social housing construction had continued at its 2009 level then an additional 31,136 social housing units would have been provided.40

Rent supplementation

There are now four schemes through which rents of low-income households living in the private rental sector may be subsidised: Rent Supplement, introduced in 1997, under the Supplementary Welfare Allowance scheme, and originally intended to provide short-term housing support for people not in work; Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS), introduced in 2004 and envisaged as providing more long-term support and available even where a householder is working; Social Housing Current Expenditure Programme (SHCEP), introduced in 2009, under which local authorities and voluntary housing bodies may enter a leasing arrangement with a private landlord with the tenant paying a rent related to their income; and HAP, introduced in 2014 and intended to be, ultimately, a replacement for Rent Supplement for households which have a long-term need for social housing.41

By 2016, these four schemes were providing rent subsidisation for almost 93,000 households – that is, for 30 per cent of all households in the private rental sector in Ireland. Expenditure on the various schemes has grown significantly, reflecting both the increased number of households being supported and rising rents. During the six-year period, 2011 to 2016, over €3.2 billion was spent on the four schemes; the allocation for 2017 is €624 million.42

Rebuilding Ireland Proposals

New social housing provision

The headline target announced in Rebuilding Ireland was the commitment to provide an additional 47,000 units of social housing – that is, housing to be supplied by local authorities and voluntary bodies – during the period up to 2021.43

The breakdown for this provision was as follows: 10,000 units to be acquired from purchases from the private market; 11,000 to be leased from the private market; 26,000 to be ‘newly built’ by local authorities and voluntary bodies.

It is immediately obvious that the proposed approach would mean a marked level of dependence on construction by the private sector so as to reach the envisaged number of acquisitions and leases (i.e., 21,000 units).

However, the target of 26,000 for ‘new build’ is also significantly reliant on private sector construction, since 4,690 units are to be acquired by local authorities and voluntary housing bodies under Part V of the Planning and Development Act. Furthermore, the 26,000 target includes 3,460 units of existing but vacant local authority housing. This would mean that under the Plan total new provision by local authorities and voluntary bodies would amount to just 17,890 units – 38 per cent of the overall target of 47,000.44

May Day March, Dublin, 2017 © DSpeirs

However, on 8 September 2017, an adjustment to the earlier approach was announced. In the Statement issued following the Housing Summit, the Minister for Housing stated that resources would now be ‘redirected away from acquisitions’ towards new building by local authorities and voluntary housing bodies. This would mean, he said, that there would be an increase of around 800 in the target for newly-built social housing for 2018.45 This, then, is a change in the manner in which the target for new provision in 2018 is to be met – but not a commitment to increase the overall supply.

Social housing and the private rental sector

In Rebuilding Ireland, ‘social housing’ is defined as not just provision by local authorities and voluntary bodies but as including housing that is privately owned and privately rented but where the State is meeting the major share of the rental costs. In this, the Action Plan is, of course, merely continuing the process, which has been going on for well over a decade, of ‘redefining’ social housing to include provision from the private rental sector. This is explicit in the title of one of the graphs in the Plan: ‘Spectrum of social housing provision forecast, 2016–2021’ and in a note to that graph which states: ‘This new social housing stock includes units and tenancies delivered through the HAP and RAS schemes on an annual basis’ (emphasis added).46

However, the Action Plan contains no discussion of the rationale for defining social housing in this way; neither does it include any exploration of the consequences of this approach for those who have to rely on social housing, particularly in terms of long-term security, or the implications of an open-ended commitment to spending public money on rents in privately-owned property rather than directly providing social housing.

HAP

Rebuilding Ireland proposes that between 2016 and 2021 a total of 83,760 tenancies under HAP will be created – a number significantly greater than the planned increase of 47,000 in the supply of social housing by local authorities and voluntary housing organisations. The Plan does not, however, state how many of these are to be new state-subsidised tenancies: the target figure includes existing long-term Rent Supplement tenancies to be transferred over to HAP, and no figure for these is provided. However, the Social Housing Strategy published in November 2014 indicated that there were at that time 50,000 long-term recipients of Rent Supplement.47

As already noted, HAP has the important benefit, as compared to Rent Supplement, of being available to those who are in employment. However, Rebuilding Ireland claims several further advantages for the scheme. It states, for example, that HAP tenants have access to ‘good quality housing in communities of their choice’.48 In reality, the choice of location for households availing of HAP is strictly defined by the maximum rent limits which apply under the scheme. Snapshot surveys carried out by the Simon Communities in Ireland of available properties for rent in eleven locations on three consecutive days in November 2016, March 2017 and August 2017 highlight the gap between the market rents being demanded and the limits imposed under HAP (and Rent Supplement). On the chosen dates in November 2016, just 17 per cent of the total properties advertised for these areas were within the HAP rent limits; in March 2017, only 12 per cent were within the limits; in August 2017, the situation had deteriorated still further so that just 9 per cent were within the limits.49

Rebuilding Ireland also claims that: ‘HAP continues to offer to many families stable and supported social housing’.50 HAP tenancies are no more ‘stable’ than other tenancies in the private rental sector; the reality is that the sector in Ireland does not offer long-term tenancies and any tenancy is liable to end if the landlord can show that they need to use the property for a family member, intend to sell it, or want it vacated in order to carry out substantial repairs.

Voluntary housing organisations have highlighted the vulnerability of people depending on HAP to losing their tenancy and becoming homeless, including instances of people who had exited emergency accommodation into a HAP-supported tenancy, only to find themselves not too long afterwards once more facing the possibility of homelessness.51

As for the claim that tenancies are ‘supported’ – apart from the subsidisation of rents, there are no other supports for HAP tenants: they must find their own accommodation and the scheme does not provide assistance with deposits. In contrast, under the Rental Accommodation Scheme, the local authority undertakes responsibility for finding suitable accommodation and enters a leasing agreement with the landlord.

One of the most serious issues concerning HAP, which was raised even before the payment came into effect, is that households availing of the scheme are removed from the social housing waiting list as they are deemed to have their housing needs met. They are, however, entitled to be included in the ‘transfer’ list. What precisely this means in practice, and in different local authority areas, seems to be unclear. The issue should be addressed by allowing all HAP tenants who so wish to remain in the housing waiting list.

Empty Properties

With the deepening of the housing crisis, there has been increasing discussion of the role which vacant houses and other empty properties might potentially play in addressing unmet housing need.

The 2016 Census showed that despite a fall of 42,421 in the number of residential units that were vacant, as compared to the 2011 Census returns, there were still 140,120 houses and 43,192 apartments vacant in April 2016, giving a total of 183,312 (excluding holiday homes). The vacancy rate in 2016 was 9.1 per cent (in 2011, it was 11.5 per cent). This is markedly out of line with the level of vacancies that might be expected to arise from a normal turnover in ownership or use, or because of refurbishment being undertaken.52 The Second Quarterly Progress Report on Rebuilding Ireland notes, for example, that the vacancy rate in the Netherlands is 2.5 per cent.53

While some rural counties have particularly high vacancy rates, unused housing is also prevalent in urban areas. The five city areas of Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway and Waterford, together with their suburbs, have a cumulative total of 42,421 vacant housing units (23 per cent of the national total).54 These are, of course, the areas where housing demand, including assessed need for social housing, is at its highest.

Obviously, not all vacant houses are capable of being returned to use in the foreseeable future – for example, many are located in areas where there is low housing demand – and not all vacant properties of other kinds are suitable for conversion into housing. However, it is clear that the redesign, refurbishment and re-use of vacant properties could play an important role in meeting housing need – both in the private sector, where the availability of such properties for purchase or rent could help relieve pressure within the sector, and in the social housing sector.

As Rebuilding Ireland points out, utilising empty buildings not only reduces the need for the additional infrastructure which is required in the case of new housing development, thus saving both money and time, but it can address the aesthetic and social problems, and ultimately the blighting of neighbourhoods, which arise when buildings are allowed to remain empty, especially in large numbers.

In addition, bringing vacant properties back into use rather than building new housing may have important environmental advantages, in terms, for example, of enabling utilisation of existing public transport networks. Furthermore, the refurbishment of buildings may result in a lower lifecycle carbon output than might be the case with new building.55 Such environmental considerations are particularly important given the need for Ireland to significantly lower its greenhouse gas emissions in order to meet its national and international climate and energy obligations.

Rebuilding Ireland Proposals

Rebuilding Ireland put forward a number of proposals to enable empty houses be brought back into use, and also in relation to how other empty buildings previously used for commercial purposes might be converted into residential units.

In terms of meeting social housing need, the Action Plan announced two new programmes to enable empty housing units be used for this purpose.

The first was the ‘Housing Agency Vacant Housing Purchase Initiative’, under which the Housing Agency was to be allocated a ‘rolling fund’ of €70 million to buy portfolios of empty housing units from financial institutions which it would then sell on to local authorities and voluntary housing bodies, with the income from these sales being used by the Agency to acquire the next tranche of properties.56 In total, 1,600 properties are to be acquired in this way by the end of 2020. The Progress Report on Rebuilding Ireland for the first quarter of 2017 stated that: ‘To date the Housing Agency has had bids accepted on 330 dwellings and over 130 contracts have been closed’.57

The second scheme was the ‘Repair and Leasing Initiative’, under which the owner of a vacant home could receive funding to bring it up to the required housing standards; the house would then be leased, for a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 20 years, to a local authority or a voluntary housing body for use in meeting social housing need. A target of 800 leases under the scheme was set for 2016, and it was envisaged that, in all, 3,500 properties would be leased up to 2021, with an allocation of €140 million over the period.58

However, by summer 2017 it had become evident that there was a very low level of response to this scheme, especially in large urban areas where the need for social housing is greatest. It has been suggested that, in these areas, both demand for rented properties and rental yields are so high that owners who are willing to rent would not need the funding being offered in order to undertake repairs, nor would they be interested in entering a leasing agreement with a local authority or social housing body when they could potentially receive a much higher rental return by letting the property on the private market.59

Subsequent to the publication of Rebuilding Ireland another programme was announced – the ‘Buy and Renew’ scheme which is to enable local authorities to purchase vacant privately-owned properties, remediate them and use them for social housing. In terms of funding, €25 million was allocated to this scheme in 2017 and €50 million in 2018.

Notably absent from the proposals in Rebuilding Ireland was any reference to possible sanctions in cases where owners leave houses vacant over a prolonged period. Yet the role which such measures could play has been frequently alluded to in public discussion of the issue of empty homes in the last number of years. For example, in 2016, the Housing Agency suggested that penalties should be considered in the case of long-term vacancies in areas where there is high demand for housing.60 The Dáil Special Committee on Housing and Homelessness in its Report in June 2016 recommended that a specific tax on vacant homes be introduced.61 Furthermore, the Committee made the general recommendation that: ‘The Government should explore how the use of compulsory purchase orders might increase housing supply.’62

More recently, it appears that the Government is now prepared to consider the question of the taxation of empty properties. This is welcome. Measures proposed should cover not only empty homes but properties that were previously used for commercial purposes. Furthermore, it would be important that taxation rates would increase if the properties concerned continued to remain vacant and, after a certain period, empty properties should become liable to being compulsorily purchased.

Conclusion

With the issuing of the Homelessness Policy Statement in February 2013 Ireland made an official commitment to adopting a ‘housing-led’ response to homelessness. This approach, the Statement said, ‘is about accessing permanent housing as the primary response to all forms of homelessness’.

In other words, a housing-led response recognises that although additional support services may be required by some people exiting homelessness, the key requirement is always adequate, affordable and secure accommodation. One of the consequences of a housing-led policy is that the need for emergency accommodation is greatly reduced and such accommodation is used for a limited period only, before people are enabled to move into a home.

Yet even as a ‘housing-led’ approach was being adopted as Ireland’s official response to homelessness, the mainstream housing policies being pursued were increasingly making this approach unrealisable – and were, in fact, serving to generate rising levels of homelessness. Nearly five years after the publication of the Homelessness Policy Statement, Ireland now has its highest-ever level of recorded homelessness, with twice as many people in emergency accommodation in August 2017 as had been at the beginning of 2015. Provision of such emergency accommodation, far from being phased out, has had to be significantly increased, particularly in response to the three-fold rise in family homelessness which has occurred since January 2015.

At the core of housing policy in Ireland over the past twenty years has been an increasing reliance on rent supplementation in the private rental sector to meet social housing need and the associated unwillingness to ensure that local authorities and voluntary housing bodies have the remit and the funding to supply new housing on a scale sufficient to meet most social housing requirements. In addition to being the key factor in the growth of homelessness, this policy has resulted in a more than three-fold rise since 1996 in the number of households on local authority waiting lists and in increasingly lengthy waiting times for social housing.

Rebuilding Ireland, the Government’s official housing strategy up to 2021, adheres to that approach to meeting social housing requirements. Although it promises that 47,000 additional social housing units will be provided by local authorities and voluntary bodies in that period, it also envisages a continued and indeed increased reliance on the private rental sector to provide for social housing need. By implication, the Plan accepts that the high level of public expenditure on rent supplementation which this entails will not just continue but increase even beyond its current level of more than half a billion euro per annum.

It is clear that a very different policy approach is urgently required. There is need for a commitment to the principle that long-term social housing need will be met through local authority, voluntary sector, and co-operative provision. It may be argued that even if a decision is made now to depart from the approach that has characterised the past two decades it will take many years to provide the large-scale supply of social housing that is needed. This may be true. But if that decision is not taken, then the time for achieving a better, more secure and affordable system for meeting social housing needs will become ‘never’.

Notes

1. See: Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Homeless Persons January 2015’ (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/homelessness/other/homeless-persons-december-2015) and Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, Homelessness Report August 2017 (http://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/homeless_report_-_august_2017.pdf).

2. SAFE Ireland, No Place to Call Home: Domestic Violence and Homelessness, The State We Are In, Dublin: SAFE Ireland, 2016; see also: The State We Are In, 2016: Towards a Safe Ireland for Women and Children, Dublin: SAFE Ireland, 2016, pp. 14–16.

3. ‘Direct Provision Statements, Dáil Éireann Debate, Vol. 945, No. 1, Thursday, 30 March 2017.

4. Focus Ireland, ‘New Government homeless figures for June show that the situation is ‘worse than ever before under every single category, and getting worse”, Press Statement, 4 August 2017 (www.focusireland.ie/press/new-government-homeless-figures-june-show-situation-worse-ever-every-single-category-getting-worse-2/).

5. Focus Ireland, ‘New Focus Ireland Figures Show Number of Families Becoming Newly Homeless in Dublin Every Month Hits an 18 Month High’, Press Statement, 1 September 2017 (https://www.focusireland.ie/press/8403-2/).

6. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Statement by Minister Murphy on August Homeless Figures’, 29 September 2017 (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/homelessness/august-homeless-figures-published).

7. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, Dublin, July 2016 (http://rebuildingireland.ie/Rebuilding%20Ireland_Action%20Plan.pdf).

8. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Homeless Persons January 2015’; Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, Homelessness Report August 2017.

9. Ibid.

10. Rebuilding Ireland, Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness: Third Quarterly Progress Report, May 2017, p. 12.

11. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, Homelessness Report August 2017.

12. See, for example, Kathy Walsh and Brian Harvey, Family Experiences of Pathways into Homelessness: The Families’ Perspective, Dublin: The Housing Agency, 2015, pp. 26–32; Peter McVerry SJ, ‘Homelessness’, Working Notes, Issue 76, May 2015, p. 4.

13. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, p. 34.

14. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Minister Murphy publishes the May National Homeless Figures and outlines the ongoing solutions and plans to address homelessness’, Press Statement, 30 June 2017 (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/homelessness/minister-murphy-publishes-may-national-homeless-figures-and-outlines-ongoing).

15. The measures which were outlined in Rebuilding Ireland included general social housing allocations, the use of the enhanced HAP (Housing Assistance Payment) scheme, provision of Rapid Build housing, and the acquisition of empty housing units by the Housing Agency for onward sale to local authorities and approved housing bodies (see: Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, pp. 34–35).

16. ‘Minister Murphy publishes the May National Homeless Figures and outlines the ongoing solutions and plans to address homelessness’, Press Statement, 30 June 2017.

17. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Statement by Minister Eoghan Murphy following Housing Summit’, Friday, 8 September 2017 (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/homelessness/statement-minister-eoghan-murphy-following-housing-summit).

18. Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, The Provision of Emergency Accommodation to Families Experiencing Homelessness, Dublin, July 2017; Rory Hearne and Mary P. Murphy, Investing in the Right to a Home: Housing, HAPs and Hubs, Maynooth: Maynooth University Social Sciences Institute, 2017.

19. Rory Hearne and Mary P. Murphy, op. cit., p. 26.

20. Ibid., p. 31; p. 34.

21. Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, op. cit., p. 12.

22. The study by Rory Hearne and Mary P. Murphy, Investing in the Right to a Home: Housing, HAPs and Hubs, indicates that, of the 1,003 families in emergency accommodation in the Dublin Region in February 2017, almost 400 had been in such accommodation for longer than one year and 40 for longer than two years (p. 25).

23. Rebuilding Ireland, Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness: Third Quarterly Progress Report, May 2017, p. 14.

24. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, p. 37.

25. Dublin Region Homeless Executive, Dublin Region Spring Count on Rough Sleeping the Night of 4th April 2017 (http://www.homelessdublin.ie/rough-sleeping-count).

26. ‘Statement by Minister Eoghan Murphy following Housing Summit’, Friday, 8 September 2017.

27. Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission, op. cit., p. 12

28. Department of Environment, Community and Local Government, Homelessness Policy Statement, Dublin, February 2013.

29. Rebuilding Ireland: Third Quarterly Progress Report, p. 20.

30. ‘Statement by Minister Eoghan Murphy following Housing Summit’, Friday, 8 September 2017.

31. Better Outcomes Brighter Futures: The National Policy Framework for Children and Young People 2014–2020, Dublin: Stationery Office, 2014.

32. Irish Coalition to End Youth Homelessness, ‘What you can do’ (https://www.endyouthhomelessness.ie/what-can-you-do/).

33. Housing Agency, Summary of Social Housing Assessments 2016: Key Findings, Dublin, December 2016.

34. Ibid., Table 2.8: Length of Time on Record of Qualified Households, 2013 and 2016, p. 18.

35. Michael Punch, The Irish Housing System: Vision, Values, Reality, Dublin: Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, 2009, p. 40.

36. John Blackwell, A Review of Housing Policy, Dublin: National Economic and Social Council (NESC Report No. 87), 1988, Table 8.1, p. 175.

37. Michael Punch, op. cit., Figure 2, p. 5.

38. Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government, ‘Overview of Activity under Social Housing Provision Programme by Year’ (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/social-housing/social-and-affordble/overall-social-housing-provision).

39. Ibid.

40. Rory Hearne, ‘A Home or a Wealth Generator? Inequality, Financialisation and the Irish Housing Crisis’, in James Wickham, Cherishing All Equally 2017: Economic Inequality in Ireland, Dublin: TASC, 2017, p. 82.

41. Daniel O’Callaghan, Analysis of Current Expenditure on Housing Supports, Dublin: Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, July 2017.

42. Calculated from data in: Department of Social Protection, Annual Statistical Information Report, 2015; RAS Current Expenditure Programme 2011 to date (http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/social-housing/social-and-affordble/overall-social-housing-provision) and Daniel O’Callaghan, op. cit., p. 10.

43. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, pp. 43–48.

44. ‘Social and Affordable Housing’, Dáil Éireann Debate, Vol. 934, No. 1, Tuesday, 17 January 2017 [P.Q. 497].

45. ‘Statement by Minister Eoghan Murphy following Housing Summit’, Friday, 8 September 2017.

46. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, Graph 10, p. 46. The redefining of social housing is evident also in some of the other terminology used in the document, such as its references to ‘a range of social housing outcomes’ (p. 8); ‘State-supported housing’ (p. 13); ‘social housing supports’ (p. 43).

47. Department of Environment, Community and Local Government, Social Housing Strategy 2020: Support, Supply and Reform, Dublin, November 2014, p. 45 (http://www.housing.gov.ie/sites/default/files/publications/files/social_strategy_document_20141126.pdf)

48. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, p. 48.

49. Simon Community, Locked Out of the Market VI: The Gap between Rent Supplement/HAP Limits and Market Rents, Snapshot Study, January 2017; Locked Out of the Market VII: Snapshot Study, May 2017; Locked Out of the Market VIII: Snapshot Study, August 2017, Dublin: Simon Communities of Ireland, 2017 (http://www.simon.ie/Publications/Research/).

50. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, p. 48.

51. Kitty Holland, ‘Housing Assistance Payment risks homelessness – experts’, The Irish Times, Friday, 28 April 2017; ‘Are we just going to end up homeless every year?’, The Irish Times, Friday, 28 April 2017. See also Rory Hearne and Mary P. Murphy, Investing in the Right to a Home: Housing, HAPs and HUBs, op. cit., pp. 18–19.

52. Housing Agency, Tackling Empty Homes: Overview of Vacant Housing in Ireland and Possible Actions, Dublin: Housing Agency, May 2016, p. 8.

53. Rebuilding Ireland, Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, Second Quarterly Progress Report, February 2017, p. 51.

54. Central Statistics Office, Census of Population 2016: Profile 1 – Housing in Ireland, Vacant Dwellings, Interactive table: StatBank Link E1069, ‘Permanent Housing Units by Occupancy Status and Vacancy Rates 2011 to 2016 by Aggregate Town Size, Census Year and Statistic’ (http://www.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=E1069&PLanguage=0).

55. Verena Weiler, Hannes Harter, and Ursula Eicker, ‘Life cycle assessment of buildings and city quarters comparing demolition and reconstruction with refurbishment’, Energy and Buildings, Vol. 134, January 2017, pp. 319–28; Peter Eskilsson, Renovate or Rebuild? Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, 2015 (http://bioenv.gu.se/digitalAssets/1534/1534981_peter-eskilsson.pdf); Empty Homes Agency, New Tricks with Old Bricks: How Reusing Old Buildings Can Cut Carbon Emissions, London: Empty Homes Agency, 2008; Anne Power, ‘Does demolition or refurbishment of old and inefficient homes help to increase our environmental, social and economic viability?’, Energy Policy, Vol. 36, 2008, pp. 4487–4501.

56. Rebuilding Ireland: Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, p. 50; p. 80.

57. Rebuilding Ireland, Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness, Third Quarterly Progress Report, p. 15.

58. Ibid., p. 53.

59. Valerie Flynn, ‘Too few knocking on door of repair and leasing fund’, The Sunday Times, 9 July 2017; Laoise Neylon, ‘Owners of vacant homes turn down deals to use them’, Dublin Inquirer, 2 August 2017; Olivia Kelly, ‘Vacant property owners turn down €32m grant scheme’, The Irish Times, 10 August 2017; Olivia Kelly, ‘Virtually ‘no interest’ in State-funded housing refurb scheme’, The Irish Times, 10 August 2017.

60. Housing Agency, Tackling Empty Homes: Overview of Vacant Housing in Ireland and Possible Actions, Dublin: Housing Agency, May 2016, p. 8.

61. Houses of the Oireachtas, Report of the Committee on Housing and Homelessness, Dublin, 17 June 2016, p. 47.

62. Ibid., p. 139.

Peter McVerry SJ is a member of the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice team and a Director of the Peter McVerry Trust which provides a range of services in response to homelessness.

Eoin Carroll is Deputy Director and Social Policy and Communications Co-ordinator with the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice.

Margaret Burns is Social Policy Officer with the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice.