Keith Adams and Louise Brangan

Keith Adams is a Social Policy Advocate at the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice. Dr Louise Brangan is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Strathclyde and, most recently, the author of The Politics of Punishment: A Comparative Study of Imprisonment and Political Culture (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021).

Introduction

This essay pieces together the history of Ireland’s prison system. It does this by looking at prison from the formation of the State and tracing the changing penal priorities, policies, and practices up to the present day. In the short history of our nation, the prison was at one time shaped by an admirable, but now largely forgotten, humane pastoral penality, which gave way to an express punitive sentiment in the 1990s. This history should matter to those of us interested in penal reform and social justice today. In recovering Ireland’s history of penal policy, an attempt is made to develop what Nellis has called “a historically tutored memory” so as “to ensure that our penal heritage is properly remembered.” This can remind the Irish Prison Service of “its roots and its achievements, its turning points, its lost opportunities, its past ambitions,” but also “its still unrealised possibilities.”[1]

Many involved in the building of the newly independent Irish Free State in 1922 were former prisoners. While policymakers and prisoners can seem to occupy diametrically opposed positions in contemporary Ireland’s social hierarchy, this divide did not always exist. Prisoners and former prisoners were active and prevalent in Irish political and civic life until the 1960s.[2] As we approach the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the Irish State, the archetype of the prisoner politician may have largely disappeared[3] but prisons have been ever-present during this time. The basic formula remains the same; a person is found guilty of a crime, as defined by the State, and if it is considered serious enough, then serves a sentence in a penal institution whereby the debt to society is considered paid.[4]

When surveyed over a longer period, seemingly imperceptible shifts in penal priorities, policies and practices become much more obvious. Following a brief sketch of the penal infrastructure inherited from Britain in 1922, this essay will outline how penal scepticism and Catholic communitarian values had a formative effect shaping Ireland’s penal policy in the 1970s. With humane pastoral penality of the 1970s understood as Ireland’s unique approach to lessening the problems of the prison, it becomes necessary to discuss the often overlooked irony that Ireland’s punitive turn was the result of a modernising and progressive social period in our history. The essay will conclude with a consideration of the role of human rights discourse within the Irish penal system, how it may legitimise current penal policy and practice, and what it might mean for the future.

Inheritance of Penal Infrastructure, 1922-1960s

Ireland became independent following the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921. The nascent Irish Free State inherited a prison estate of nine local prisons, four convict prisons, and one borstal.[5] Ireland’s colonial past shaped initially trenchant penal reform views within government. In November 1922, the first Minister for Home Affairs (with responsibility for justice, including prisons), Kevin O’Higgins, in one of his first statements to the newly established Free State parliament, laid out a scathing critique and the need for radical reform of Irish prisons:

“There is not a member of this present government who has not been in jail. We have had the benefit of personal experience and personal study of these problems, and although we have never discussed them, I think we would be unanimous in the view that a change and reform would be desirable. Personally I can conceive nothing more brutalising, and nothing more calculated to make a man rather a dangerous member of society, than the existing system.”[6]

Central to O’Higgins’s entreaty was his experience of being a prisoner under British rule. With the ending of the War of Independence and the Irish Civil War, political prisoners were quickly released, resulting in a rapid decline in the prison population. The daily average population in custody in 1922 was under 700 people. Compared to other parts of Great Britain at that time, Ireland had a similar rate of imprisonment with England and Wales – 29 prisoners per 100,000 of population – and significantly lower than Scotland which had 52 prisoners for the same number of population.

In the decades following the State’s independence, the overall picture of prison policy has been broadly accepted as “essentially one of stasis”[7] with minimal changes occurring in the prison system until the early 1960s. Yet, it is necessary to think about what is considered stasis, stagnation, or plain disinterest within early penal policymaking. If a proliferation of policy documents, strategy papers and regulations are a key benchmark of progress, then this early period certainly had little activity of import. As the penal-welfarist turn[8] was accelerating in the US and the UK during post-war years, the notable highlight of Irish penal development was the 1947 Prison Rules, which was the exception in this period of penal minimalism by the Irish State.

Ostensibly the new Prison Rules were designed to replace the existing British Prison Rules. However, the 1947 Rules were introduced at a time when the imprisonment of IRA members was occurring after the conclusion of the Second World War[9] which had led to an increased public interest in the Irish prison system.[10] The new rules did represent the first attempt by an independent Irish Government to lay out the principles and regulations which undergird the day-to-day life of an Irish prison, and how prisoners could expect to be treated and what rights they could claim. Rogan suggests the new statutory instrument was not intended as a new grand vision for the Irish prison system but was rather “promulgated in response to more immediate political manoeuvrings.”[11]

If, on the other hand, this early period between Independence and the 1960s is judged by a different metric – by the number of prisons and the people contained within – then the diagnosis of inertia may only partially illuminate Ireland’s penal culture in the early twentieth century. While a “progressive welfarist and professionalised vision of penal reform”[12] may have been lacking, this period was empirically categorised by lowering prisoner numbers and prison closures, provided for by the 1933 Prisons Act. By 1947, only five prisons were in operation, with a daily average number of prisoners of 584 (67 were women).[13]

This trend of decreasing prison committals and the overall population in Irish prisons was to continue from Independence until the late-1950s, dipping to less than 400 prisoners,[14] and then remaining flat until the late 1960s.[15] In 1965, there were only 560 people in Irish prisons.

Viewed through a modern penal reformist lens, this period may be interpreted as one of stagnation and inaction. The understanding of how change occurs within a reformist position often relies on incrementalism; a series of smaller steps or milestones being put in place first, before a tipping point is reached where the ultimate goal is achieved. But if the ultimate goal is to close prisons and reduce prisoner numbers, especially with minimal governmental confrontation, then the early decades of the prison system ought not be viewed with such pronounced disappointment. Yes, fewer changes were being implemented to impact the day-to-day life of the prisoner but, in the background, what we would now consider the ultimate goal of penal reform was being realised with relatively little fuss and fanfare. A tepid penal culture may have existed but the system was not in pure stasis. In contrast with today’s modus operandi of penal policy development, evident in the plethora of reports, strategies and legislation, the first four decades had, despite an absence of any stated philosophy of imprisonment, witnessed steadily reducing numbers.

Prison Scepticism and Communitarian Ideals, 1970s

However, considerable changes began to emerge in Irish penal policy by the 1970s. At the beginning of the decade, the prison population was still low, comprising 749 prisoners in total (almost all male). Even as the number of prisons and prisoners began to rise towards the end of the decade, the number of prisons was at its lowest. Categorised as either ‘ordinary’ or ‘subversive,’ the adult male prisoners were accommodated within three prisons: Mountjoy, Limerick and Portlaoise. Prisons were managed by the Prison Division, based within the Department of Justice, comprising of a small group of civil servants.

Within the space of a few years, the prison estate more than doubled, with seven adult male prisons in total, as prison numbers began to rise.[16] Seeking to counteract the phenomenon of overcrowding and the ensuing criticism, the Irish Government took the step to expand the capacity of the prison estate. The outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland presented a challenge for the prison system in the Republic due to the inherent challenge of housing politically motivated prisoners, combined with a general increase in the prison population.[17]

Yet, an impressive and humane penal transformation occurred in Ireland in the 1960s and 1970s, making this period of Irish imprisonment in some ways unrecognisable from the torpor of the previous four decades. New thinking around prisons began to emerge in the early 1960s[18] with the establishment of the Training Unit, a specialised unit in the Mountjoy campus. The Training Unit was a significant milestone in Irish penal policy as it was Ireland’s first purpose built prison, but it also had a unique philosophy that marked it out as a progressive form of penal thinking.[19] In the early 1970s, and at a time of economic prosperity, the Training Unit was devised to provide vocational training to equip prisoners for reintegration, reforms of educational provisions and the provision of post-release accommodation. The central ethos of the design was to be “less incapacitative and confining.”[20]

Ireland also established its first open prison at Shelton Abbey, and four full-time psychologists were employed alongside the inaugural positions of Directors of Probation, Education and Co-ordinator of Work and Training.[21] And perhaps most significantly, temporary release was enthusiastically expanded as a means to reduce the impact of imprisonment on both the prisoner and his family. Temporary release meant prisoners were increasingly released for short spells mid-sentence or fully released before the sentence was complete. Regular amnesties at religious seasons – Easter and Christmas – were common, along with mass releases during events such as the papal visit in 1979.[22] Compared with today’s increasingly restrictive criteria to qualify for temporary release, few crimes or length of sentence disqualified a prisoner from eligibility.

These forms of imprisonment were underpinned by new ideas of rehabilitation, which had begun to enter Irish policy discourse.[23] However, rehabilitation had a distinct meaning in Ireland. Irish government administrators during the 1970s conceived of rehabilitation as broadly as possible. Rehabilitation did not mean correction or reducing offending. Indeed, such aims were explicitly stated as not the “primary objective of imprisonment.”[24] Instead, policymakers argued that the outcomes of rehabilitation must be understood in terms of the prisoner’s whole life, their social and personal relationships, their well-being, and not limited to reoffending rates:

While “rehabilitation” is not the primary objective of imprisonment it is nevertheless an important and valid objective. It is intrinsically good and should not be abandoned simply because evidence does not prove that it is “successful”. What is to be the measure of success? Is it to be that the prisoner never again engages in criminal activity, or is never again caught, or is never convicted again, or is not convicted again within a certain length of time, or engages in criminal activity less serious in nature than his original offence? What about the qualitative improvement in the prisoner’s approach to living, his relationships with family and friends, his involvement in community activities, his willingness to help and support others, his physical and mental well-being?[25]

This reflected a more humanitarian understanding of change, one rooted in a social view of prisoners as people first, not as offenders. Rehabilitation here was explicitly connected to the qualitative idea of an ‘approach to living’: being kind and supportive to friends and family; committing less serious offences with less regularity; or being in a better frame of mind and physical health. Thus the concept of rehabilitation employed was multifaceted and not tied solely or even mainly to criminal justice metrics.

Rehabilitation, viewed this way, was also more ambitious and humane than merely reducing crime and criminality. It was interested in making better citizens, healthier people, and happier family members, rather than reformed criminals.

In approaching the concept of rehabilitation, and accepting those in prison were people first rather than fundamentally criminal, Irish prison policymakers made the aims of prisoner rehabilitation more achievable because the idea of success had a wider set of more holistic criteria. Hence, some amount of re-offending was tolerated given that this was not instrumentally equated with rehabilitation. Consequently, prison expertise and support agencies aimed:

to equip the offender with educational, technical and social skills which will help him to turn away from a life of crime, if he so wishes. However, even if the offender on release does not turn away from a life of crime, those services can be regarded as having achieved some success if they bring about an improvement in the offender’s awareness of his responsibilities to himself, his family and the community.[26]

It was explicitly understood and accepted that prisoners, like us all, were perceived to be in a state of becoming. Change can be subtle and incremental, and therefore recidivism was not necessarily a failure of rehabilitation. This penal thinking reflects an understanding of change as something personally and socially complex, and thus beyond the capacity of a particular intervention or programme to realise. If a person achieved other kinds of personal change after imprisonment this meant those penal interventions had been a success. This tolerant and humane view was important in shaping rehabilitation policy in Ireland in the 1970s. It supported a less instrumental understanding of prison programmes. People in prison were to be supported in their relationships, employment and wellbeing because these were intrinsically good, not because they were predictors of reduced reoffending. What was seen as significant and meaningful was personal transformation to the lives of former prisoners, their treatment of their family, their health, and wellbeing and their place in the community. To prioritise reducing reoffending first and foremost would have rendered negligible the many forms of post-prison success and transformation that they sought.

So the problems of Irish prison population were being met with new penal techniques that were reintegrative, supportive, and sought decarceration, rather than attempting to reduce recidivism or produce a crime control effect. How do we make sense of this peculiar turn of events? How were these prison regimes justified?

Ireland’s approach to imprisonment in the 1970s has been conceptualised as a “pastoral penality.” This was distinct from progressive penality or penal welfarism – the penal culture that had prevailed in the UK and USA until the 1970s – which located the locus of the problem within the prisoner. The prisoner was seen to be in need of individualised and expert treatment in order to be rehabilitated and ultimately reintegrated back into society. Penal welfarism therefore has an optimistic view of prison.[27]

The distinction of the Irish pastoral penal policy was, first, the prisoner was viewed not as a defective person with skewed attitude and amoral values. Instead, they were understood as someone who most likely had fallen on hard times, crime was seen as a result of poverty and a lack of opportunity, which was felt to be endemic in Ireland. There was empathy with the prisoner. But crucially, “prisoners were understood to still be members of society,”[28] a fact that was recognised and reiterated through the heavy use of temporary release.

Secondly, that the prison, and not the prisoner, was viewed as problematic. The prison was viewed as inherently harmful to social cohesion and individual well-being. The Minister for Justice noted in the Dáil chamber in 1970 that the prison environment was “basically unsuitable for encouraging individuals to become adequate and responsible members of normal society.”[29] As such, there was a deep scepticism of the prison and the positive claims made towards its usage. Indeed, the Division described penology as “an area where folly abounds.”[30] There was an implied sense that new modern techniques of intervention overstated the good prison could achieve, and they overlooked the damage the prison always causes. Hence, the rationale behind new psychology and education services, like chaplains in the decades previous, were to assist prisoners to cope with the pains of imprisonment, rather than to regulate their potential for reoffending.

Thirdly, this scepticism of the prison was rooted in Ireland’s traditional and conservative social order, which prioritised the values of community and family. As other countries were focused on furthering individual rights, which are a core aspect of a liberal democracy, Ireland was a “nation largely defined by its communitarian Catholic culture, where family life was paramount to the national order.”[31] Penal prudence equally flowed from a view that “collective efficacy”[32] of family and community and the Church were all superior sites of social and moral regulation, rather than government intervention. Combined, these forces of empathy and communitarian ideals caused the prison in Ireland to be seen sceptically, and understood as detrimental to those conservative Catholic values of family and community.

Of course, no system ever totally realises its ideals in practice. Yet here, in the 1970s, when the Department was known to be at its most secretive and insular, there was the flowering of a distinctly Irish humane and lenient politics of punishment. Ireland clearly did not replicate the Anglophone punitive turn[33] in the 1970s, instead it had matched the Nordic countries in its “restrained inclination to imprison” and was among the European countries with the lowest rates of incarceration.[34] By the mid-1990s, however, Ireland’s prison policy had taken a bewilderingly swift and decisive punitive turn.[35] Social and political scandals in the 1990s destabilised Ireland’s pastoral penal culture and saw its values, and thus its lessons, slip from view.

1980s to Present: Different Progressive Policy, Same Punitive Endpoint

It is now well known that from the 1970s in the UK and USA, penal welfarism gave way to a punitive model of imprisonment. Pastoral penality, Ireland’s unique form of progressive penal policy, found a similar fate.

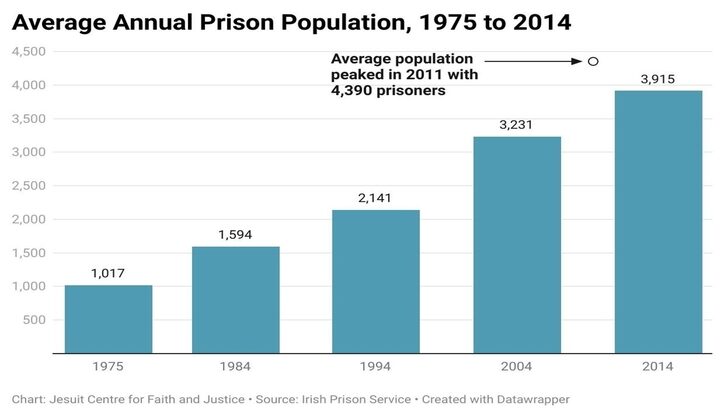

In the two decades between 1965 and 1984, the Irish prison population almost trebled, rising from 560 people to almost 1,600 people. By the mid-1980s, a punitive ethos emerged in the Irish prison system, with increased numbers and overcrowding becoming the most recognisable trait of prison life. Independent reports started to become a more common occurrence.

Two significant reports were published in quick succession which shaped policy discourse. In 1983, the Council for Social Welfare, a committee of the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference, published The Prison System outlining the rights of prisoners. Prompted by ongoing discussions, the Whitaker Report was established with an accompanying committee and chairperson to provide an account of conditions in Irish prisons and to provide recommendations for reform.[36] The report was unequivocal in its values as it asserted that “the fundamental human rights of a person in prison must be respected and not interfered with or encroached upon except to the extent inevitably associated with the loss of liberty.”[37] The department also published a report, The Management of Offenders, which reiterated their commitment to a less total form of incarceration, where their primary aim was to maintain a cap on prisoner numbers.

Despite this, in the 1990s, a new program of prison building was initiated. O’Donnell describes this as “the central paradox of Irish penal policy,” where there appears to be a political consensus on penal restraint, yet numbers continually rose to new levels.[38] Rogan has suggested that one of the risks of the Irish State having an under-developed conceptualisation of imprisonment, whether for good or ill, and a flexible ad-hoc approach to penal reform, is that prison policy is left susceptible to the vagaries of national events or the whims of electoral politics.[39] However, it was not electoral politics but instead a confluence of socio-political factors and events that conspired in the 1990s to lead to a dramatic penal transformation.

Ireland had been inching further away from the traditional society and the perceived social efficacy of the family had dwindled. At the same time, the Catholic Church’s authority seemed to collapse, irreparably undermined through a series of exposés.[40] Crime risen through the 1980s. By the 1990s, drugs, gangland crime, and joyriding were all major national issues. Then, in June 1996, Garda Detective Jerry McCabe was murdered during the attempted robbery of a post office vehicle by the IRA in Limerick. This was quickly followed by the assassination of journalist, Veronica Guerin, which proved to be a tipping point for a nation already disorientated by the speed of its social changes. A moral panic and political emergency gripped the national mood, with the government coming under attack for their restrained approach to law and order.

In this febrile atmosphere, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil – like their Anglophone counterparts – understood the political advantage to be secured by presenting as ‘law and order’ parties. There can be a tendency to present this period of penal transformation as the product of entrepreneurial vigour and opportunism on the part of John O’Donoghue and Fianna Fáil. But this belies much deeper social change that was happening in Ireland, and only by understanding this can we understand the dramatic punitive turn that was to occur in the country.

There was a feeling that something must be done about Ireland’s new dangerous classes; that the government could no longer be so moderate and discreet. Someone must take charge. Without the Church as a shadow authority structure, the Irish government of the 1990s had to carry this greater responsibility: to intervene, to protect communities from crime, to take control, to direct social relations. These forces combined to radically alter the conduct of government and the meanings of Irish imprisonment. There was a reinvention and expansion of the political apparatus.[41] The Irish Prison Service was established, placing prison management physically outside the Department of Justice, which also underwent a transformation, renamed as the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform in 1997. The Department was now intended to be focused on developing policy.[42] The prison in Ireland was reorganised as a tool of crime control.

The prison estate was intentionally expanded, with expenditure rising from £96m in 1993 to £189m by 1999.[43] Prisoner numbers rose exponentially: mandatory minimum 10-year sentences were introduced for non-violent drug possession charges,[44] the temporary release system was severely restricted, the use of remand was increased – quite the opposite of what had preceded it. The nation appeared to be on an “incarceration binge.”[45] This took place to such an extent that:

the changes in Ireland’s imprisonment regime were so clearly punitive; the prison lost something… It was a concerted effort at changing the imprisonment regimes so that their walls were less permeable, that people moved less freely from prison back into society, that their exclusion and punishment could be more certain and that the prison sanctions of the court could be better enforced. These changes reorganized the prison as a law enforcement tool, a crime control mechanism and an expression of intemperate social feelings.[46]

By July 2004 the average daily prison population stood at 3,231. This compares with 2,141 in 1994 and 1,594 in 1984.[47] The most recent Irish Prison Service figures have the average daily population in custody as 3,824 people.[48]

Michael McDowell later continued in this mode of penal excess, providing the vision and ardour for the proposed construction of a new large prison at Thornton Hall in north county Dublin, with 2,200 places.[49] Plans for the mega-prison were mothballed in 2011 following the global economic crash of 2008 and opposition from many quarters.[50] Despite official reports recommending a cap on prison numbers, the trifecta of political opportunism, economic surplus, and electoral support opened the way for a more punitive prison system.

The curious context of the Irish punitive turn is seen when we recall that it also took place within the context of a modernising and progressive social period. This was a time in which pastoral penality could have flourished, when opportunities for work and education proliferated. What had supported the pastoral penal policy was an empathy for the prisoner, which itself was rooted in Ireland’s traditional social order and communitarian class structure. In Celtic Tiger Ireland, as Irish society was becoming more affluent and liberal it was also becoming deeply divided, “the punitive carceral developments that took place reflected Irish society’s growing estrangement from the prisoner and the annulment of his social belonging.”[51] Thus, the prison became a new and vital tool of social control.

The Future, Legitimisation and Scepticism

During the early years of the American ‘War on Terror’, the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were supported by a torture regime centred in Guantanamo Bay, and nightmarishly exposed in the photos from Abu Ghraib prison. Reflecting on this time, Samuel Moyn, a law professor at Yale, suggests that the success of the activist campaign to end State-sanctioned torture did not bring the war to an end and had unintended consequences. In Moyn’s own words, “the noble cause of prohibiting torture has functioned to legitimate ongoing war.”[52] He suggests that the ostensible end-goal of the anti-torture campaigning was the delegitimisation of the invasion. In essence, it was an anti-war movement. Ultimately, it failed as it simply delegitimised one form of war craft and legitimised another emergent form of war. Protocols and legal procedures were implemented with considerable fanfare so that policies like extra-judicial killings, geo-location tracking, and drone strikes could be “properly humanized and regulated.”[53] Thinking to the future, Moyn argued that, in order to avoid such paradoxical consequences, lessons should be learned; if a person wants to be against war, then they have to be against war and not just against particular features or by-products of war which are most brutal.

In a similar vein, Moyn’s astute reflections on torture should cause anyone involved in penal policy—whether politician, civil servant, academic or activist—to take pause. Like the anti-torture campaigners, there may be unintended consequences for being simply against certain features of the Irish penal system in its current form.

A particular form of confinement may be delegitimised in the public’s eyes while another form, equally pernicious in effect, if not in description, may emerge. The harm of the system to prisoners may be maintained as the system enjoys fresh legitimacy by heeding tactically to campaigning and the language of civil society. This entrenchment is then placed beyond challenge in public discourse, established as a new status quo.

Since their emergence in the 1980s, the role of human rights institutions and discourse has had a positive impact on Irish prisons. The most rudimentary of prison estate upgrades became possible, most notably with the drastic reduction of “slopping out,”[54] the refurbishment of the prison estate, the expansion of education and occupational training, and the creation of oversight and inspection frameworks. Human rights discourse has matured and developed among penal policy stakeholders to the degree where human rights are regularly cited within official documentation. The Irish Prison Service, in their 2020 Annual Report, situate their operation within “the parameters set out in Irish, European and international human rights law” with the stated aim to “promote equality and human rights through our policies and procedures.”[55]

Yet, to adapt Moyn’s theorising on war and torture for a moment more, by focusing on the incidental features of imprisonment in Ireland, something unexpected has occurred. Those people and agencies who helped to seed the human rights discourse[56] with the Irish Prison Service (and the Department of Justice) would no doubt be surprised by the increased and widespread usage of prison as a sanction for even the most inconsequential crime such as shoplifting or social order offences.[57] Might it be the case that as we improved prisons, we also increased the utilisation of prison?

While prison inspection reports, by the Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture and the domestic Inspector of Prisons, have repeatedly highlighted Ireland’s lack of compliance[58] with internal prison standards and human right frameworks, progress has undoubtedly been made, despite significant time lags.[59] Certain forms of imprisonment with particularly egregious aspects, such as the treatment of IRA prisoners in the 1940s, have been delegitimised. But, in their place, another model of imprisonment has been legitimised which may both endure and be protected from serious scrutiny. A model where people, many of whom have been failed by the welfare institutions of the State, are warehoused in prisons of ‘best practice’ which rather than restoring the prisoner, only serve to linguistically screen us from the harm we are inflicting on them.

Many penal policy stakeholders now believe that a ‘humane’ form of imprisonment is both possible and being realised in practice. But the fundamental questions that were posed but never wrestled with in the first Dáil – about the coercive over-reach of much that occurs in prison and its larger detrimental effect on society – can pass unnoticed as we aspire to incremental change of a system that must instead be subject to a fundamental overhaul.

This current understanding of imprisonment in Ireland is a clean break from the penal scepticism of the civil servants in the 1970s. Conscious of both the harms caused by imprisonment, and the grinding poverty experienced by those who found themselves within prison, there was a healthy scepticism of the utility of prisons. So much so, that the locus of rehabilitation and reintegration of the prisoner could only be found in the communal; within their family and local community. Every opportunity was sought to allow people in prison the opportunity to access temporary leave or early parole.[60] There was no doubt that even with better conditions, prison causes tremendous harm to prisoners and irreversible damage to their familial and social connections.

Unlike the anti-war movement discussed by Moyn, with the aim of ending wars, there is no developed or developing discourse on prison abolition in Ireland to end imprisonment. While abolitionist positions can take different forms and vary by degrees, the common thread through them all is the commitment to reduced prison numbers and widespread availability of community-based sanctions and restorative justice practices. The core essence of pastoral penality is the acknowledgement by governments that the prison, rather than the prisoner, is “fundamentally problematic and often harmful.”[61] Only when this re-ordering of thinking occurs can there be penal retrenchment and a turn away from expansion. With the zeal of the newly converted, and the abandonment of any scepticism or unbelief, the Irish Government is continuing its love affair with the prison. As part of a current €175 million upgrade and expansion of penal infrastructure, plans for a large prison on the 67-hectare Thornton Hall site are again under consideration by the Department of Justice and the Irish Prison Service.[62]

Conclusion

Prisoners and former prisoners played a prominent role in establishing Ireland and the subsequent project of state-building. Yet, social proximity or empathy for prisoners by policymakers (and wider society) can seem undetectable in 21st century Ireland. However, the Centenary provides an opportunity to recover and reappraise the values and ethos which are central to our Republic.

This essay is a reminder of the penal reforms that are possible when we focus on the problems of the prison rather than problems of the prisoner. This lesson has contemporary resonance for Ireland today. Currently, the Irish government endeavours to envision a new future for imprisonment in a spirit of reform, seeking out ways to move the prison closer to strategic goals of consistency and reducing reoffending. But the government also aspires to have greater use of open prisons, community-based sanctions and new forms of ‘decarceration’.[63]

In the current Irish climate of willingness for penal reform, and perhaps even an aspiration for more pastoral forms of punishment, we might pause and see the immediate history of Irish imprisonment and government as a source of its future improvement. What made Ireland’s prisons impressive during the 1970s was not that they had sophisticated oversight models, or that it had consulted international experts. Instead, Irish prisons were “ruled through leniency.”[64] They did not seek to reform the prison, but to reduce it.[65] A return to this humane outlook would be a return to something – not merely imagined but once in operation – that was not eradicated but marginalised and side-lined for a period. This can be a source for the revivifying of a more sceptical and compassionate kind of imprisonment and penal politics. It is possible to envision a future where our penal systems are governed by leniency. If we are willing to replicate what those in charge of our prisons knew intuitively in the 1970s, we must be willing to see the prison not merely as a site of punishment but as a social institution that can significantly impact not just the lives of people who have been imprisoned, but the fabric of Irish social life and our collective sense of national well-being.

Footnotes: