“…the reach of the present extends into the far future.” [1]

Henry Shue

Introduction

Some truths bear repeating. First, we were all once the “future generations” ourselves, existing only as potential until the day we were conceived and born. Second, each of us will most likely, at some point, meet someone from the future—whether our children, nieces, nephews, or grandchildren. Third, the well-being of “future generations” relies on the world and society we shape in the here and now. Lastly, these future generations, whose futures hinge on today’s political choices, have no vote.

By advocating for a solidarity that transcends time, this essay argues that future people deserve as much consideration as those alive today. In other words, we should strive to be good ancestors.[2] Extending this logic, our political systems should also seek to govern with future generations in mind.

The essay begins with a thought experiment and an outline of some philosophical rationales for intergenerational solidarity. It then discusses how certain temporal cognitive biases can hamper our ability to think beyond the present, followed by insights from contemporary philosophers on fostering long-term thinking. In the latter half of this piece, I provide a timeline of global governance efforts for future generations and highlight innovative examples of futures-governance worldwide. It concludes by reflecting on how Ireland’s next government might embrace intergenerational solidarity and disrupt short-termism.

Ultimately, this essay contends that, despite human psychology and the short-term nature of political cycles, we can break from governance inertia and promote intergenerational solidarity, specifically through the creation of a Future Generations Commissioner.

Thought Experiment

Imagine you are blessed with three children. If each of them has an average of 2.2 children, in 250 years, you would have approximately 50,000 descendants. That is an enormous web of people, all connected to you and living in a future yet unwritten—a span comparable to the time since the Industrial Revolution.

Now picture a grandchild or great-grandchild living in the 2080s. Visualise their face, their age. What kind of world do you wish for them? Most people envision a life with a secure home, a loving family, nutritious food, peace, and an education permitting secure work and financial stability. Now ask yourself: How do you want them to feel?

Philosophies of Intergenerational Solidarity

That imagined descendant, however, is not yet alive and current political systems often overlook their needs. Should we, the “duty-bearers”, extend solidarity to future generations—the “entitlement-bearers”? [3] If so, why?

A number of arguments exist to wrestle with this question. The first argument that can be offered is moral equality, which asserts that all individuals, regardless of when they exist, should be regarded as free and equal. Temporal location, like geographic location, is an arbitrary facet of identity and should not determine one’s entitlements.[4] The second is the luck-egalitarian argument, where if we believe inequalities outside individual control are unjust, then the inequality of birth in a different time also merits redress.[5]

A third argument centres on “sufficientism”, which claims that all people should have enough means (resources) in order to achieve the ends required for a life of dignity and agency.[6] Depriving future generations of these essentials cannot be justified. Lastly, the negative obligation argument holds that we have a duty not to cause harm that would not occur otherwise. If our actions today undermine future generations’ well-being, we must uphold intergenerational solidarity and act responsibly.[7]

Temporal Cognitive Biases

Yet despite clear philosophical rationales for being good ancestors to those yet to come, we all know from lived experience that the capacity for imagining possible futures does not make those futures so. Our tendency to subordinate future satisfaction to current pleasure—the psychological term is temporal discounting—continuously serves us badly. From putting off that run, having that extra glass of wine despite an early start, or failing to squirrel away sufficient money into our pensions, the tension between the present and future is with us every day. Additionally, we tend to value immediate, though smaller, rewards more than long-term larger rewards with greater pay-off.[8]

Our brains, shaped by millennia of evolutionary forces, have not adapted to the rapid industrial and technological changes of recent centuries. We are often ensnared by what philosopher Roman Krznaric calls “the tyranny of the now”[9] or presentist thinking—a state exacerbated by media and technology that aggressively compete for our attention.

Ways to Think Long

If we are committed to being good ancestors and breaking free from the present bias that traps us, how can we cultivate a mindset that embraces long-term thinking?

In The Good Ancestor, Krznaric suggests several “ways to think long.”[10] First, adopt a deep-time perspective, seeing ourselves as part of the vast continuum of time and the ecosystem. Deep-time thinking encourages us to consider the thousands of years it takes for an inch of soil to form or the millions for uranium-235 to decay. Engaging with ancient geology, going on “deep-time walks,”[11] or exploring resources like the Long Time Academy[12] can be practical ways to nurture this perspective.[13]

Second, engage in cathedral thinking by embarking on ambitious projects that may not be completed within our lifetimes, such as those behind the Pyramids, Great Wall, or Notre Dame. Those who laid the keystones and foundations of these projects believed in a future they wouldn’t witness, given the length of time construction took in those days. What legacy do we wish to leave for future generations?

Finally, adopt a legacy mindset. In 1888, a wealthy, traditionally successful man was reading what was supposed to be his brother’s obituary in the newspaper. He suddenly realised that due to a mistake by the editor, the obituary he was reading was actually his own. It read “The Merchant of Death is Dead,” [14] and described how, as the inventor of dynamite, he had gained his wealth by helping people kill each other. Deeply troubled by this account of his legacy, the man decided to leave most of his fortune to fund awards for those whose work most benefited humanity. His name? Alfred Nobel, founder of the Nobel Prizes.

The story of Nobel’s epiphany after reading his accidental obituary illustrates the power of contemplating one’s legacy. He shifted his legacy from the Merchant of Death to that of a benefactor for humanity.

Humans often shy away from the fact of their own mortality, yet it is one of the few things we all have in common. Research into the psychology of leaving a legacy identifies three different kinds of legacy. The first category is the individualistic legacy, which benefits you. An example of this is making a philanthropic donation that bears your name, such as a building or a statue or, indeed, investing a prize after yourself. The second category is the relational legacy, which involves leaving something for someone you are related to. Bequeathing an inheritance is the obvious example. The final category is the collective legacy, which benefits whole groups, such as a university or society at large.[15] When we reflect on our impact, what do we want to leave society? What will our legacy be, and how can we become good ancestors?

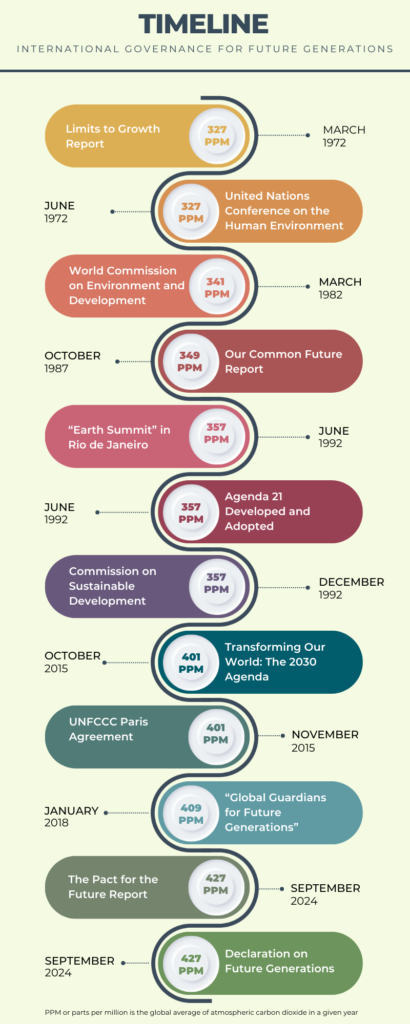

Timeline of International Governance for Future Generations

Up to present day with data centres, airport expansions and intensive farming, economic actions which ignore environmental consequences have been the the norm. During the 1960s post-war economic boom, the push to increase food production led to widespread use of the insecticide DDT.[16] Scientist and author Rachel Carson chronicled the devastating effects of DDT on ecosystems in her book Silent Spring.[17] Carson’s work sparked the environmental movement, inspiring the rise of groups like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth in the early 1970s. But her advocacy met fierce resistance, including from the American President Ronald Reagan, who viewed environmental protection as a threat to economic growth.

Shortly after Silent Spring’s publication, MIT scientists developed a computer model to project interactions among population growth, agricultural production, resource depletion, industrial output, and pollution. Their conclusions, published in Limits to Growth,[18] were sobering: Earth’s resources likely cannot sustain current economic growth much beyond 2100, even with advanced technology. Predictably, their findings angered political leaders who saw them as a call to dismantle the economic status quo.

In the same year that Limits to Growth was published, 1972, the first-ever global conference on the environment took place in Stockholm. A decade later, the UN established the World Commission on Environment and Development, led by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, to examine the clash between human activity and environmental health. The Commission’s 1987 report, Our Common Future,[19] offered a groundbreaking definition of sustainable development: “[d]evelopment that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This definition continues to shape global policy today.

Five years later, in 1992, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development or “Earth Summit” was held in Rio de Janeiro,[20] where the first agenda for Environment and Development, known as Agenda 21, was developed and adopted. The Rio Summit was the largest environmental conference ever organised to that point, bringing together over 30,000 participants, including more than one hundred heads of state. The summit represented a major step forward, with international agreements made on climate change, forests, and biodiversity. Among the summit’s outcomes were the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, Principles of Forest Management, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, and Agenda 21, which required countries to draw up a national strategy of sustainable development. The summit also led to the establishment of the UN Commission on Sustainable Development.

Over twenty years later, in 2015, all UN Member States adopted Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development,[21] which articulated 17 Sustainable Development Goals all directed towards meeting the definition of sustainable development:

We are determined to protect the planet from degradation, including through sustainable consumption and production, sustainably managing its natural resources and taking urgent action on climate change, so that it can support the needs of the present and future generations…We will implement the Agenda for the full benefit of all, for today’s generation and for future generations.[22]

Also in 2015, 193 UN Member States agreed to the UNFCCC Paris Agreement, which set the global community the challenge of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, and again explicitly articulated the value in terms of intergenerational equity:

Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.[23]

In 2018, Mary Robinson’s Foundation for Climate Justice proposed that “Global Guardians for Future Generations”[24] be appointed by the Secretary General of the United Nations to provide a voice for future generations and to help achieve fairness between generations in the context of sustainable development. The Elders have since been established, counting Gro Harlem Brundtland as one of their members, and the group is currently chaired by Mary Robinson.

More recently, in September 2024, more than fifty years on from the first UN conference on the environment and the Limits to Growth report, the UN has adopted The Pact for the Future[25] which highlights the importance of coordinated global action to protect future generations from crises in health, war, climate and biodiversity breakdown, and recalcitrant challenges in the financial system which have led and continue to lead to inter- and intra-national poverty and inequality, and an annexed Declaration on Future Generations.[26]

Innovative Governance for Future Generations

Before the end of 2024, we will elect a new Government to serve a five-year term. From a deep time perspective, this is a pinprick on the calendar of human evolution, yet given our proximity to planetary boundaries and tipping points, those we elect will make decisions that will have ramifications for centuries to come. While short-term political cycles are meant to prevent prolonged rule by any single party, they often prioritise immediate gains over long-term sustainability. In this system, future generations—those with the most at stake—remain voiceless.

While short-term political cycles are meant to prevent prolonged rule by any single party, they often prioritise immediate gains over long-term sustainability. In this system, future generations—those with the most at stake—remain voiceless.

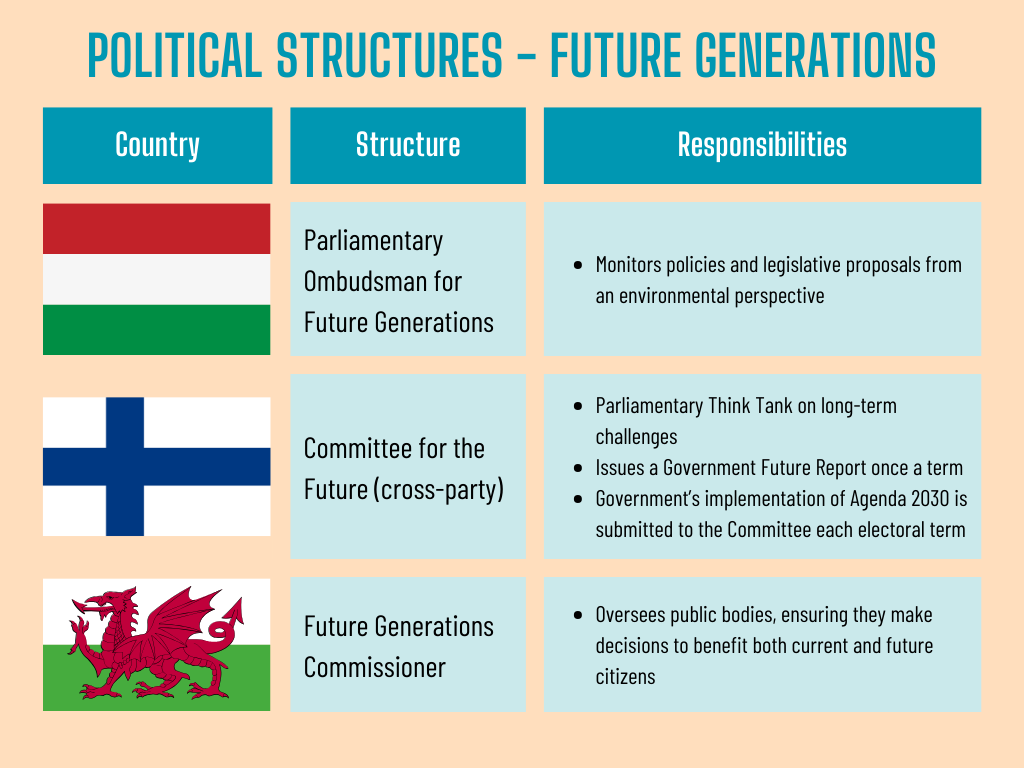

Yet change is emerging. In recent years, multiple countries and regions have increasingly embraced political structures aimed at ensuring the welfare of future generations.

In Hungary, a Parliamentary Ombudsman for Future Generations monitors policies and legislative proposals to ensure they pose no irreversible threats to the environment.[27] Finland has a cross-party Committee for the Future,[28] which functions as a parliamentary think tank on long-term challenges, issuing a Government Future Report at least once per term. Since 2017, that Finnish Government’s implementation of Agenda 2030 is also submitted to the Committee for the Future during each electoral term.

Wales offers a pioneering example. In 2015, it enacted the Well-being of Future Generations Act, embedding sustainability goals into its legislation and establishing a Future Generations Commissioner.[29] The Commissioner oversees public bodies, ensuring they make decisions benefiting both current and future citizens. The Act has influenced major shifts: two-thirds of the Welsh transport budget now supports public transit; a future-focused school curriculum emphasises resilience; and prosperity is measured not by GDP growth, but by fair, low-carbon jobs.

Indigenous cultures worldwide, however, have long understood the importance of intergenerational solidarity. For example, the Seventh Generation Principle, rooted in Haudenosaunee philosophy[30] dictates that decisions today should sustain the world for seven generations into the future. This ancient wisdom reminds us that sustainable thinking is not new—it’s simply essential.

Disrupting Governance Inertia

How can Ireland’s next Government overcome the inertia of short-term political cycles to effectively govern for future generations? In 2023, Green Party TD, Marc Ó Cathasaigh, introduced the Commission for Future Generations Bill,[31] which seeks to establish an independent body to assess the sustainability of government actions and provide guidance on policies impacting the future. Although it has passed the Second Stage debate, the bill will not advance further in this Government’s term—a missed opportunity to make Ireland a global leader in safeguarding the welfare of future generations, as envisioned by former Taoiseach Leo Varadkar who wanted Ireland to be “the best country in the world to be a child.”[32]

In 2024, Coalition 2030—a civil society coalition advocating for the Sustainable Development Goals—studied the feasibility of establishing a Future Generations Commissioner in Ireland.[33] Through interviews with civil servants, politicians, and civil society leaders, they found broad support for the role as a Future Generations Commissioner would align well with existing frameworks like the National Planning Framework and the Well-being Framework. Echoing this, the Joint Committee on Environment and Climate Action’s 2023 report on biodiversity recommended the creation of an Ombudsman or Commission for Future Generations, empowered to defend long-term human and ecological well-being:

…the establishment of a new Ombudsman for Future Generations with the resources of an office, or a Future Generations Commission to protect the long-term interests of human and ecological well-being for current and future generations.[34]

Such a role needs true independence to critically assess departmental decisions. The current Welsh Future Generations Commissioner is clear that the office acts as a mentor to public bodies, favouring collaboration over enforcementas“[t]he office uses the carrot more than the stick approach as this is where most collaboration and positive change happens.”[35]

Long-Term Thinking and Human Potential

Martin Seligman and colleagues outlined how it is the unique human capacity for mental time travel that allows us to consider possible different outcomes, possible futures, and collaborate to make the ones we want to see manifest come to fruition.[36] In arboreal terms, Krznaric describes our capacity for long-term thinking as our “acorn brain,”[37] signposting to the trust in the future demonstrated by a tree-planter. We also have unparalleled capacity for planning, strategising, and collaborating. We have gone to the moon, developed quantum computing, and cured diseases that wiped out hundreds of thousands of our ancestors. We can, and are, evolving, and this must be matched by governance.

Across the globe, forward-thinking governance structures are emerging, giving substance to intergenerational solidarity. What started as a concept in 1972 has now sparked entire UN Summits, and ideas like Future Generations Commissioners and Parliamentary Committees are gaining ground. But the urgency is clear. Global emissions rose 1.3% in 2023, far outpacing the pre-COVID average of 0.8%, and the latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report warns that we are on track for between 2.6°C and 3.1°C of warming by 2100.[38]

Like a relay, our moment in history depends on how well we pass the baton. To “future” well, we must act with intent, ensuring each decision—personal and political—moves us toward sustainable outcomes. By establishing a Future Generations Commissioner, Ireland’s next government could anchor intergenerational equity in policy, making a real, lasting commitment to those who will inherit this world.

Reflection for the Future

At the outset, I asked you to reflect on how you want your ancestor in the 2080s to feel. At the end of this piece, what is your answer? Psychologist Antonio Damasio’s somatic marker hypothesis suggests that it’s not enough to merely imagine a desired future; we must connect emotionally to it.[39] When we feel the stakes for future generations, we are driven to make better, bolder choices today.

Homo sapiens have existed for about 300,000 years, yet more people will likely live in the future than have ever lived in the past. Our existence today is owed to generations who cultivated food, built wonders, developed medicines, and invented tools. We do not remember their names, yet they’ve made this time the best era to be human. Now, it is our turn to become architects of the world to come. What legacy will we leave for those who follow? What do we want them to thank us for? As Krznaric reminds us, if we take seriously the human dignity of others, there is hope enough to counter any resignation:

We’re in one of the most vulnerable positions that humanity has been in. But I don’t think that our fate is preordained. I think that there’s a good chance that we’ll wake up fast enough if we could take seriously this idea that all people are created equal and that our lives matter just as much no matter where we are on the Earth or no matter when we live.[40]

Meaghan Carmody works as a Senior Sustainability Advisor for Business in the Community Ireland. She holds an MA in International Political Economy from University College Dublin and has worked in the Irish NGO sector for a decade on issues of sustainable development.

[1] Henry Shue, ‘High Stakes: Inertia or Transformation?’, Midwest Studies In Philosophy 40, no. 1 (2016): 63.

[2] Roman Krznaric, The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short Term World (London: Random House, 2020).

[3] Simon Caney, ‘Climate Change and the Future: Discounting for Time, Wealth, and Risk’, Journal of Social Philosophy 40, no. 2 (2009): 163–86.

[4] John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2005).

[5] Cécile Fabre, Justice in a Changing World (Cambridge: Polity, 2007).

[6] Campbell Brown, ‘Priority or Sufficiency… or Both?’, Economics & Philosophy 21, no. 2 (2005): 199–220.

[7] Shue, ‘High Stakes’.

[8] This is a curious phenomenon in neuroscience known as hyperbolic discounting. For more, see James E Mazur, ‘The Effect of Delay and of Intervening Events on Reinforcement Value’, Quantitative Analyses of Behaviour 5 (1987): 55–73.

[9] Krznaric, The Good Ancestor, 5.

[10] Krznaric, The Good Ancestor.

[11] Explore the Climate Emergency via a transformative walking experience with Deep Time Walk, see ‘Deep Time Walk – Explore Earth History and Geological Time’, https://www.deeptimewalk.org/image/jpg. Or write a letter to your future self at ‘Longpath’, https://www.longpath.org.

[12] See ‘The Long Time Academy’, n.d., https://www.thelongtimeacademy.com/home.

[13] For more resources, check out The Long Time Project and the School of International Futures, ‘The Long Time Project’, 1 February 2023, https://www.thelongtimeproject.org; ‘School of International Futures’, School of International Futures, accessed 12 November 2024, https://soif.org.uk/.

[14] Evan Andrews, ‘Did a Premature Obituary Inspire the Nobel Prize?’, History, 23 July 2020, https://www.history.com/news/did-a-premature-obituary-inspire-the-nobel-prize.

[15] Ella Saltmarshe, ‘How To Stretch Time’, The Long Time Academy, November 12, 2021, https://podcasts.apple.com/ie/podcast/part-two-how-to-stretch-time/id1589516917?i=1000541579750.

[16] The common name for a organochloride known as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane.

[17] Rachel Carson, Silent Spring (London: Penguin Books London, 1962).

[18] Donella H. Meadows et al., ‘The Limits to Growth’ (Rome: Club of Rome, 2 March 1972).

[19] World Commission on Environment and Development, ‘Our Common Future’ (Geneva: United Nations, October 1987), 37.

[20] United Nations, ‘United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992’, United Nations, accessed 7 November 2024, https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992.

[21] United Nations, ‘Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ (Geneva: United Nations, 2015), https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf.

[22] United Nations, 5.

[23] United Nations, ‘United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Paris Agreement’ (Geneva: United Nations, 2015), 2.

[24] Mary Robinson Foundation Climate Justice, ‘Global Guardians: A Voice for Future Generations’ (Dublin: Mary Robinson Foundation Climate Justice, January 2018), https://www.mrfcj.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Global-Guardians-A-Voice-for-Future-Generations-Position-Paper-2018.pdf.

[25] United Nations General Assembly, ‘The Pact for the Future’ (Geneva: United Nations, 20 September 2024), https://www.un.org/pga/wp-content/uploads/sites/109/2024/09/The-Pact-for-the-Future-final.pdf.

[26] United Nations Summit of the Future, ‘A Declaration on Future Generations’, United Nations, accessed 6 November 2024, https://www.un.org/en/summit-of-the-future/declaration-on-future-generations.

[27] ‘Gyula Bándi’, Network of Institutions and Leaders for Future Generations, accessed 6 November 2024, https://ourfuturegenerations.com/gyula-bandi/.

[28] ‘Committee for the Future’, Eduskunta Riksdagen, accessed 7 November 2024, https://www.eduskunta.fi:443/EN/valiokunnat/tulevaisuusvaliokunta/Pages/default.aspx.

[29] ‘Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015’, The Future Generations Commissioner for Wales – Comisiynydd Cenedlaethau’r Dyfydol Cymru, accessed 7 November 2024, https://www.futuregenerations.wales/about-us/future-generations-act/.

[30] According to the Indigenous Corporate Training Inc., the first recorded concepts of the Seventh Generation Principle date back to the writing of The Great Law of Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Although the actual date is undetermined, differing dates place this writing at any date from 1142 to 1500 AD.

[31] Houses of the Oireachtas, ‘Commission for Future Generations Bill 2023 (Bill 8 of 2023)’, 30 May 2024, https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/bill/2023/8.

[32] Grainne Ni Aodha, ‘Taoiseach Leo Varadkar Aims to Reduce Wait for Child Healthcare and Assessments by 2025 | Irish Independent’, Irish Independent, 26 December 2022, https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/taoiseach-leo-varadkar-aims-to-reduce-wait-for-child-healthcare-and-assessments-by-2025/42243755.html.

[33] Audry Deane and Catherine Carty, ‘A Call to Action for Future Generations: Taking Irish Leadership on Intergenerational Equity Forward’ (Coalition 2030, September 2024), https://coalition2030.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/A-Call-to-Action-for-Future-Generations-Online-Version.pdf.

[34] Joint Committee on Environment and Climate Action, ‘Report on the Examination of Recommendations of the Citizens’ Assembly Report on Biodiversity Loss’ (Dublin: Houses of the Oireachtas, December 2023), 44.

[35] Deane and Carty, ‘A Call to Action for Future Generations: Taking Irish Leadership on Intergenerational Equity Forward’, 7.

[36] Martin E. P. Seligman et al., Homo Prospectus, 1st edition (New York: OUP USA, 2016).

[37] Krznaric, The Good Ancestor, 17.

[38] United Nations Environment Programme, ‘Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures Hit New Highs, yet World Fails to Cut Emissions (Again)’ (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme, 2023).

[39] A. R. Damasio, ‘The Somatic Marker Hypothesis and the Possible Functions of the Prefrontal Cortex’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 351, no. 1346 (1996): 1413–20.

[40] Ella Saltmarshe, ‘How We Got To NOW’, The Long Time Academy, November 5, 2021, https://podcasts.apple.com/ie/podcast/part-one-how-we-got-to-now/id1589516917?i=1000540852008.