The recommendation of the Whitaker Report in regard to the provision of an open prison for most of the women who are imprisoned was never acted upon. Now, two decades later, rather than attempting to explore alternatives to the detention of women in closed prisons, the Government plans to replace the larger of the country’s two prisons for women – the Dóchas Centre – with an even bigger prison, to be located on the grounds of the new prison complex at Thornton Hall.

This article will look at the implications of, firstly, the relocation of Dóchas from its present inner-city site, on the grounds of Mountjoy Prison, to the Thornton Hall site in north County Dublin and, secondly, the proposal to increase in the capacity of the Centre.

In terms of its facilities, regime and services, the existing Dóchas Centre has many positive features. Furthermore, its location close to Dublin city centre is a significant advantage in terms of facilitating family visits and accessing important services.Moving the women’s prison to the new location far from the city centre is likely to have several negative consequences.

Maintaining Links with Families

Research on the demographics of the prison population is extremely sparse, especially in relation to women prisoners.3 The research by Carmody and McEvoy, A Study of Irish Female Prisoners, conducted over ten years ago, indicated that the majority of women entering prison lived in inner city Dublin and had been brought up there. In all, 82 per cent came from Dublin, with 71 per cent from the inner city.4 A high percentage were mothers and were the primary carer of their children before going to prison.

Detailed up-to-date figures on the place of origin of women in prison are not available: the most recent Prison Service Annual Report (2006) does not provide a breakdown of where women in prison come from. A calculation based on information in the 2005 Annual Report – derived from information relating to the countries or Irish counties given as the home addresses of women committed to the Dóchas Centre in that year – suggests that over 50 per cent of the women had been living in Dublin at the time of their committal to the prison.5

Previously it had been a guiding principle of the Department of Justice that prisoners be accommodated as near as possible to their own homes.6 However, moving the women’s prison to the Thornton Hall complex will mean, in effect, the end of this policy as far as women prisoners are concerned.

Studies show that if family bonds are maintained ‘the chances of the prisoner going back to prison again are greatly reduced.’7 It is obvious that prisons that are easily accessible to families can assist prisoners and their families maintain these vital connections.

Transport to Thornton Hall

Whether consciously or otherwise, the assumption is frequently made that every household in Ireland has a car. While the majority do – just under 80 per cent – ownership is much less prevalent among poorer families.8 Since evidence points to an over-representation of people from lower socio-economic groups in the prison population, the issue of the availability of public transport is of critical importance for families wishing to visit a family member in prison.

In its current location, the Dóchas Centre is easily accessible from major public transport hubs: both Connolly Station and Busáras are in close proximity. Dublin Bus services pass the entrance to Dóchas and both LUAS lines are also accessible.

The Thornton Hall complex is situated approximately 10 kilometres from the current location of the Dóchas Centre on the border of Dublin and Meath. Joan Burton TD has described its location as ‘extremely isolated’.9 There is no rail service to the area, and a minimal bus service to the nearby village of Coolquay, Co. Meath.

It has been proposed that a special bus will be used to provide a link between Dublin city centre and the new complex. There are questions to be asked as to the frequency of this service, and the cost to the users. However, an even more fundamental concern is that travelling by a specially provided ‘prison bus’ will be a stigmatising experience for families.

It seems inevitable, then, that a move to Thornton Hall will result in an added burden for families of women in prison, many of whom already experience poverty and deprivation. In contrast, the Mountjoy complex has been described by criminologist Paul O’Mahony as offering ‘the best opportunity to maintain family and community links, which are essential to prisoners’ well-being and future social integration.’10

Visitors’ Centre

One of the successes of the Dóchas Centre has been its visitors’ centre which provides a humane environment for family members and others who come to visit their loved ones. It is understood that the plans to relocate the Centre include provision for a visitors’ centre. In his annual report for 2006–2007, the Inspector of Prisons noted that the visitors’ centre committee has sent a ‘carefully prepared proposal for their needs in Thornton Hall’ and had‘also requested a discussion with the architects’ but as of September 2006 they had not received a response.11 Should the Thornton Hall facility for women prisoners be built, a firm commitment needs to be made to support and finance a new visitors’ centre.

Access to Services

Difficulties with the lack of local infrastructure at the new Thornton Hall complex relate not only to sewage needs or road access but to access to a hospital and in-reach services. The Dóchas Centre has a medical unit, which is staffed by qualified and dedicated people. While it might be possible to replicate this provision in the new complex, what cannot be replicated is the ready access which the Centre has to the outpatient and accident and emergency services of the Mater Hospital. This is a considerable resource for the Dóchas Centre, especially in light of the fact that health care needs are much greater among women than among men in prison.12 People who work in the prison have indicted that the lives of women who have been attacked or who have attempted suicide or become seriously ill have been saved as a result of the Centre’s close proximity to a major public hospital.

Groups providing services to women prisoners have expressed the view that the location of the Thornton Hall site will have significant implications for them in their provision of services. In-reach services are extremely important to the Dóchas Centre and have developed in the immediate locality or are based in Dublin city centre. These include the services of a local Society of St. Vincent de Paul conference and of ‘befrienders’ who play a very valuable role in the lives of the women.

Organisations working with women who are about to leave or have left prison will also be affected. There has been no announcement by the prison authorities of financial or other support to in-reach services to enable them continue their work if the Centre is moved to Thornton Hall.

Dóchas is the Irish word for hope. It is widely acknowledged that ‘hope’ is reflected in the facilities of the Dóchas Centre and the very positive regime that exists there. While Dóchas is located within the Mountjoy complex, it is situated on the periphery of the grounds, and has a separate entrance. The Centre has distinct design qualities, with the accommodation provided in seven separate houses. Upon entering Dóchas one is struck by the positive and respectful relationship that exists between staff and inmates.

While there have been indications that the current regime will be replicated in the proposed new women’s prison in Thornton Hall, individuals and groups working with prisoners express apprehension about whether it will be possible to ensure that the positive ethos of the regime can continue. This is particularly so in light of the proposed increase in the size of the prison and its isolated location. Building a women’s prison of the size envisaged, with accommodation for at least double the number in the existing prison, will have significant implications for the type of regime that will be feasible.

Proximity to Male Prison

Studies show that the regime of prisons for women is seriously impacted upon by their proximity to prisons for men.13 This is particularly so if facilities are shared; however, it applies even if facilities are not shared but if prisons for men and women are built adjacent to each other.

The prison authorities claim that the eight individual detention facilities that are apparently to be built on the Thornton Hall site – one of which is presumably the proposed women’s unit – will be ‘practically self-contained’.14 If this means sharing visitation areas and recreational space, women prisoners, because they are a small minority in what is a predominantly male prison population, will experience added disadvantage. This has occurred in Limerick Prison, with services for women prisoners at times been severely curtailed due to over-crowding in the men’s prison.

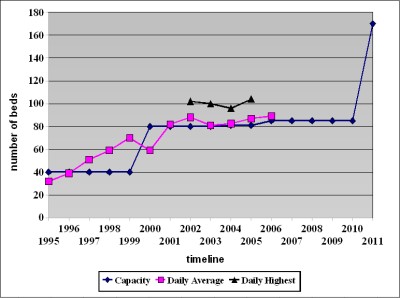

In January and February 2008, proposed figures for the overall capacity of the new prison at Thornton Hall were made public in a number of newspaper articles.15 The Director General of the Prison Service, Brian Purcell, has described the planned capacity as ‘meeting any demand for additional space for at least the next 50 years.’16 In the case of the women’s prison, the demand projections seem to be based on the two-times table: the capacity of the Dóchas Centre is at present 85 but the proposed development at Thornton Hall is for a facility to accommodate 170. An Irish Prison Service spokesman described the proposed two-fold increase in capacity as ‘future-proofing’.17

Historically, penal policy in Ireland has seemed to evolve in the absence of research findings, public discussion and coherent decision-making: it might be said that we build prisons which then shape our prison policy, not vice-versa.18 Each time there has been an increase in the number of places for women prisoners there has been an absence of an evidence-based explanation of the figure chosen.

In 1994, there were, at any one time, approximately 50 women imprisoned in Ireland, 40 of whom were accommodated in the Women’s Prison at Mountjoy.19 In that year, the Department of Justice published a five-year plan, The Management of Offenders, which stated that a 60-bed women’s prison was needed on the Mountjoy site.20 There was no explanation as to how this figure was derived – even though it represented a 50 per cent increase in the number of places for women prisoners on the Mountjoy site.

Just four years later, in 1998, the Strategy Statement 1998–2000 of the Department of Justice, Equality and Law Reform announced that the proposed new Mountjoy women’s prison would have 80 places.21

In December 1999 the Dóchas Centre opened with a bed capacity of 70 and overall accommodation for 80.

And by 2011, the proposed completion date for Thornton Hall, the main women’s prison in the country will have places for 170.23 In fact, given the manner in which the capacity of prisons has been expanded by resorting to ‘doubling up’ in what are meant be single occupancy cells, it would not be too surprising to find that, within a few years of the new prison opening, it was accommodating far in excess of this number.

Figure 1 below depicts the rapid growth of prison places for women and the dramatic infrastructural ‘future proofing’ that the Thornton Hall complex will provide.

Figure 1: Capacity of the Dochás Centre24

Many commentators have pointed out that the number of prison places provided is determined by political choices based on fiscal constraints and the level of punitiveness in society at a given time – ‘it is a simple matter of choice and a function of legislation’.25

This was acknowledged in 2000 by a sub-committee of the Joint Oireacthas Committee on Justice, Equality, Defence and Women’s Rights. In its report, the sub-committee admitted that the number of prison places ‘is to a large extent a political calculation’. The sub-committee went on to say:

[D]espite popular belief to the contrary, imprisonment rates have a very small impact on crime rates and can be lowered significantly without exposing the public to serious risk. There is little substance to what might be called the ‘hydraulic theory’ that as sentences go up, crime goes down.26

Ireland’s recent policy of building additional prison places has been set during an economic boom and in a political climate in which ‘zero tolerance’ of crime was frequently emphasised. Out of this context has come the proposal for the largest prison development in the history of the State, and the proposal to double the number of places in the country’s main prison for women. As was the case with the previous expansion in the number of places for women, there has been a lack of transparency as to the analysis undertaken to determine this figure. In contrast, proposals regarding the provision of new children detention schools have been based on a detailed analysis of projected capacity needs, as contained in the Final Report of the Expert Group on Children Detention Schools, published in March 2008.27

The fact is that building a prison to accommodate 170 prisoners goes against international best practice, which is based on the premise that smaller prisons are better.28 It also contradicts one of the principles advocated by the Council of Europe in its 1999 Recommendation to Member States (of which Ireland is one), on ‘Prison Overcrowding and Prison Population’:

The extension of the prison estate should rather be an exceptional measure, as it is generally unlikely to offer a lasting solution to the problem of overcrowding.29

An alternative solution – the retention of the women’s prison on its present site, while the remainder of the Mountjoy complex is sold – does not appear to have received any serious consideration.

The proposal that the relocation of the Dóchas Centre will be accompanied by a doubling of its capacity is being justified on the grounds that there is need to address the problem of overcrowding in the Dóchas Centre, and there is need also to provide for future needs.

Overcrowding is indeed a daily problem in the Centre: women are being accommodated in the medical centre of the facility, and there has been a resort to ‘doubling up’ in what were intended to be single occupancy cells.30

However, before the capacity of the prison is doubled, the question, ‘whom do we detain and why?’ needs to be fully explored. In reality, a significant number of women in prison are serving sentences of less than one year. Moreover, in 2005, 21 per cent of those committed were being held under immigration legislation.31 The women held due to immigration law have not committed a crime; some are waiting to be deported while others are having their asylum application processed.32 The 2006 Report of the Mountjoy Prison Visiting Committee commented that the detention of such women ‘results in short term overcrowding and the reduction of services which can be provided.’ The Committee urged that other facilities be used for this purpose.33

There are good grounds for fearing that if the new larger women’s prison is built at Thornton Hall, it will be soon filled, as happened when the present Dóchas Centre was built. Eventually, the problem of overcrowding will once more arise.

Imprisonment is only one of several possible penalties that can be used when women commit offences, and building more prison places is only one of the possible solutions to the problem of overcrowding in women’s prisons.There are other alternatives: non-custodial sentences in place of ‘prison sentences under eight months’34 – in effect, the abolition of short-term sentences; the imaginative use of imprisonment such as weekend detention;35 and the accommodation of the majority of women prisoners in low security open prisons, as recommended by the Whitaker Committee. Such alternatives would be less costly, and could provide more effective long-term solutions.

There is a strong case for saying that before the Dóchas Centre is moved or expanded to accommodate significantly larger numbers of prisoners a review should be undertaken of the use of imprisonment for women in Ireland. The ‘Review of Women with Particular Vulnerabilities in the Criminal Justice System’ in England and Wales, which was carried out by Baroness Jean Corsten and which was completed in less than nine months, could provide useful guidelines for an Irish study. 36 Such a review should take into account the recommendations of the Resolution adopted by the European Parliament on 13 March 2008 on The situation of women in prison and the impact of the imprisonment of parents on social and family life. The Resolution includes proposals in regard to prison conditions, maintaining links with families and reintegration into society.37 The purpose of a review should be to provide a clear analysis of the extent to which detention is really needed in response to crime by women, to explore whether small open prisons could meet some of the need for imprisonment, and to examine the ways in which alternative penalties could be developed.

1. Report of the Committee of Inquiry into the Penal System, Dublin: Stationery Office, 1985, p. 75.

36. Baroness Jean Corston, op. cit.