Dr Mark Mellett

Vice Admiral, Dr Mark Mellett was Ireland’s highest ranking military officer, Government’s Principal Military Advisor and member of the National Security Committee and the EU Military Committee. He now runs his own company Green Compass advocating for sustainability and is Board Chair of the Maritime Area Regulatory Authority and Sage Advocacy.

INTRODUCTION

The sense that as human beings we are separate from nature and the cosmos and the growing divide between science and religion, it is argued, are two root causes of the ecological crisis we now face. As human beings, we are part of nature, have come from the cosmos and will return to the cosmos. Unanswered questions around quantum entanglement, the dual particle and the wave nature of matter

as examples, highlight the need for a more sophisticated dialogue between science and religion

reframing our understanding of a traditional God with the birth of a new God and a deeper

understanding of our spiritual being. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ provides a paradigm through

which we can look at human beings and spirituality. He said “[w]e are not human beings having a

spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having a human experience”1 and “[l]ove is the most powerful and still most unknown energy in the world.”

As love grows with greater consciousness and unity in evolution, so too God emerges as the Omega

Point and the future of evolving life. Combining these perspectives with Philip Hefner’s request that “we entertain the hypothesis that love is rooted in the fundamental nature of reality, including the reality we call nature”2 helps us begin to construct a framework through which to look at evolution, nature and the anthropocene. It invites us to explore the prospects of a future in which rather than thinking we are separate or even could possess the cosmos, instead we accept our interbeing and the binding energy which draws all matter towards a greater wholeness. This is a wholeness in which we embrace an emerging understanding of evolution with a rejuvenated view of religion. This is a wholeness that is empowered by love as a unitive force and the fundamental energy that brings about a greater integration and a deeper understanding of God in the future with a greater consciousness, integrating science and religion with spiritual awareness leading to sustainable development.

There are many reasons to suggest that the world as we know it is at a difficult point, particularly in the context of measurable climate change effects from 2023 supporting a negative outlook:

- Highest daily, monthly and annual global

temperature anomaly; - Highest level of atmospheric carbon for

over a million years; - Highest sea surface temperatures;

- Lowest Antarctic sea-ice extent;

- Greatest gain in sea level rise;

- Highest absorbed solar radiation.

These record breaking statistics have social and security consequences including impacts on public health, migration, destruction of infrastructure and conflict. Understanding how we have come to this point necessitates a broad ranging reflection which encompasses societal, economic, technological, theological and cosmological perspectives.

Firstly, this paper examines the evolution of human beings and society commenting on religion and

how the shift from a geocentric to heliocentric perspective intensified the divide between science

and religion. Next the paper examines the consequences of negative externalities, largely driven by

a governance model where the market does not always tell the ecological truth. At this point it is

worth reflecting specifically on some case studies that are inextricably linked with the climate and biodiversity crisis. Finally, I will suggest how a transition from hierarchy to holarchy with an evolution towards the noosphere as a third phase of earth’s development after the geosphere and biosphere provides the route to sustainability. A future facilitated by courageous leadership where complexification leads to greater collective consciousness, diversity, interconnectedness and integration bridging the gap between religion and science.

FROM THE BIG BANG, GEOSPHERE AND BIOSPHERE TO THE EVOLUTION OF THE ANTHROPOCENE.

Evidence of homo sapiens can be traced back to just over 250,000 years while the cosmos has been evolving for over 13.4 billion years. The Big Bang theory posits that the very atoms that provide the energy of life were created in stars. Through the course of millions of years, following the geosphere, the

biosphere evolved and so “out of a long history of cosmic cataclysms and mass extinctions, we humans emerge. We are born out of stardust, cousins of daffodils and bonobos.”3 That said, despite the reality that we are a product of the big bang and an evolution towards greater consciousness, today, we think that as human beings it is all about us.

Human life, which has been present for less than 0.002% of the timeline since the Big Bang, has evolved as part of a global ecosystem influenced by religion and, more recently, science and technology, informing behavioural modernity, and adopting norms and principles informing values. Many of these

values are internalised, often codified into law which, in the main, are institutionalised

within the state structure and its social systems. Up to the 17th century, religion and science

worked largely hand in hand with the idea of God being intertwined with the understanding of the

natural world in which the geocentric model, endorsed by the Catholic Church, had the Earth as the

centre of the universe. Galileo however supported the Copernican model of heliocentrism which

posited that the Earth and other planets orbit the Sun. His work disrupted prevailing concepts

laying the groundwork for a new science, which dismantled aspects of Aristotelian physics that had been integrated into Christian theology for centuries. So it was that a great divide emerged between religion and science which many would say has not been adequately addressed. Religion has failed to keep pace with science and has more in common with history than reality and evolution. Similarly, science has remained absorbed with what is, rather than considering what ought to be.

Today, in most democratic states, institutional arrangements for civil society are built on a separation between Church and state which serves as an impediment to integration. Values are shared or co-created with other states such as in the case of the European Union (EU) and inter-governmental organisations like the United Nations (UN) with frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It was out of such a multilateral framework that, over 31 years ago, the Brundtland Commission published Our Common Future,4 one of the first seminal reflections to advocate a holistic approach to the key principle of sustainable development. In the decades that have followed and in the context of the norms and principles that underpin good governance and inform our values, sustainable development should be what some describe as a ‘meta-norm,’ that is, something for which self-penalisation should occur for non-compliance. There is much similarity between Brundtland’s findings and the SDGs which were originally co-sponsored by Ireland in 2015. Addressing the global challenges we face, the SDGs represent a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. In short, they are fundamental to the framework for humanitarian action and have remarkable potential as tools for accelerating convergence towards greater integration. That said, as we move towards 2030, where full implementation of the 2030 SDGs is to be achieved, it is clear that by any

measure, SDG progress, at only 15%, has stalled. 5

SECURITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE-EXISTENTIAL THREATS TO HUMANS

Robert Kagan, in the Jungle Grows Back,6 reflects on progress in terms of global peace and security over the last number of decades and suggests that there is a sense of regression. Complexities like the rise in populism, polarised politics, religious fundamentalism, state sponsored cyber/hybrid attacks and interference add to the general decline in global security weakening societal and political institutions.

Too often the rate of change or deterioration in a particular continuum has two discrete stages, first slowly, then suddenly. Such is the case with climate change and biodiversity loss which may have non-linear impacts. Many argue we are approaching tipping points which present existential threats to the

functioning of the Earth’s ecosystem with dire consequences for species including humans. A congruence of factors and tipping elements, centred on climate change, biodiversity loss, food and water security7 serve to make the problem more wicked.

An ecosystem is where the physical characteristics of an area work together with the biodiversity which exists in that physical space to form a “bubble of life.”8 With the growth in the human population and the

transition to what is now widely called the Anthropocene, biodiversity has been eroded and as a consequence, the resilience of ecosystems is reduced. Communal inter-dependencies are disrupted, replaced by rugged individualism.

A key driver to the current state of affairs is that the main economic models have failed to encompass total economic valuation (TEV) and as a consequence the importance of the goods and services we receive from ecosystems have been undervalued. The increasing recognition of the importance of biodiversity has resulted in advocates expanding the term “climate crisis” to “climate and biodiversity crisis.” But there remains a lag in our understanding of the biodiversity crisis. Diminishing biodiversity often leads to or contributes to the breakdown of ecosystems which, in turn, further exacerbate the worst

impacts of climate collapse.

Short term political decision making and market failure to incorporate the ecological truth or adopt total ecosystem valuations have resulted in negative externalities becoming part and parcel of the Anthropocene. As a result, the anthropogenic activity across the biosphere is resulting in serious second order effects in the geosphere sub elements9 with destructive impacts for example through elevated greenhouse gas emissions. Anthropogenic activity over the last 50 years has contributed to a greater than 65% loss of vertebrate wildlife10 while in the last 30 years there has been a 75% reduction in insects including pollinators 11

THE LAWS OF UNINTENDED CONSEQUENCES AND NEGATIVE EXTERNALITIES

The 6th Assessment Report (ARS6)12 by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) shows a strong interplay between the differing elements of the ecosystem and the potential for anthropogenic activity to cause damage. While a comprehensive review of ARS6 is beyond the scope of this paper, a brief examination of four key themes—marine life, carbon emissions, health and human security— is warranted.

Destruction of the Marine

Despite its importance to our biosphere, our oceans have been mistreated by humans for decades. The

premeditated 130 kilotons of subsurface nuclear test explosions; man-made disasters like the Deepwater Horizon spill; the great garbage patches of the Atlantic, Pacific and other oceans; and ocean acidification caused by the excessive absorption of CO₂ all have lasting and unpredictable consequences.

In Ireland, destruction of the ocean environment is often associated with unsustainable extractive fisheries. Cold Water Coral (CWC) reefs like lophelia pertusa flourished, along the break of the Irish continental shelf, 600 metres below the ocean surface. Associated with these reefs were deep water fish species such as orange roughy, hoplostethus atlanticus, which gathered above the corals. These fish have a lifespan of more than 200 years with some individual fish alive today also alive when Darwin sailed on the Beagle. Over recent decades CWC reefs, that took over 8,000 years to form, have been destroyed in minutes by deep water trawling that was perversely incentivised by government grant mechanisms13

Impact of Carbon Emissions

In pre-industrial times, our ecosystem was essentially balanced in terms of the release and capture of carbon. Today, the annual release of nearly 40 billion metric tonnes14 of CO2, from the burning of fossil fuels, has resulted in our ecosystem carbon sinks being saturated. In 1958, atmospheric CO₂ was at 313 parts per million (ppm)15 with some estimating this will rise by over 50% to 490 ppm before we reach

net-zero. There is an inextricable correlation between increased CO₂ emissions and temperature rise

with implications for human health and security.

Climate Change and Health

The impact of COVID-19 has been seismic. At least 10,000 virus species have the ability to infect

humans but, at present, the vast majority are circulating silently in wild mammals. However, changes in climate and land use will lead to opportunities for viral sharing among previously geographically isolated species of wildlife. Many argue that intensifying pathogen emergence can be attributed to climate breakdown, biodiversity loss, habitat degradation, and an increasing rate of human and wildlife interactions16

The Global Hunger Index17 points to alarming levels of hunger in nine countries with serious levels

in a further 34. The World Economic Forum has identified that about a quarter of the world’s people face extreme water shortages, primarily caused by the climate crisis, that are fuelling conflict, social unrest and migration.18 The World Resources Institute has identified that 17 countries face “extremely high” levels of water stress, while more than two billion people live in countries experiencing “high” water stress19 with over 800 water related conflicts recorded since 2010.20

Climate Change and Human Security

Over the last 15 years, the world has become less peaceful according to the Global Peace Index produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace in 2023. The previous Global Peace Index stated that 71 countries have deteriorated in peacefulness; with a significant proportion of these countries having a high or very high risk from climate linked incidents such as floods, tropical cyclones or droughts. Earth’s climate is more sensitive to human- caused changes than scientists have realised21 with a general acceptance that it will be 1.5oC hotter than it was in pre-industrial times within the 2020s and 2oC hotter by 2050. By 2070,

extremely hot zones could make up almost 20 percent of the land, which means that a third of humanity could potentially be living in uninhabitable conditions.22 The effects of climate change and environmental degradation will intensify food and water insecurity for poor countries, increase migration, precipitate new health challenges, and contribute to biodiversity loss.

The three brief case studies below are part of the mounting world evidence of climate change

induced human security challenges. According to the IPCC, the additional pressures brought by

climate change will increase vulnerability and the risk of violent inter/intra-state conflict.23

Migration

The Irish Defence Forces have seen at first hand the interplay between climate change and security.

In 2015, following a courageous decision by the then Taoiseach Enda Kenny, the Naval Service undertook

deployments to the Mediterranean, initially as part of a bilateral response with Italy to address

the growing irregular migration route across central Mediterranean. Some of those embroiled in the

crisis were forced into irregular migration because of climate change. In the following years, the Navy rescued over 20,000 people, while witnessing hundreds of people drown and recovering many bodies. In one case, a fourteen-year-old boy was murdered just before rescue because he dared to complain that family members were suffocating below the decks of the overloaded craft.

Tri Border Region Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger and Western Africa

The practical impacts of climate change and security is acutely apparent at the porous borders of

the Sahel, particularly in places such as the Tri Border area of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, where traditional ways of living that have sustained communities are now

jeopardised. For thousands of years, the ‘open access’ property rights regime facilitated practices

such as pastoralism, enabling nomadic movement of Fulani Herders and their animals in concert with

settled Dogan farmers. Declining resources associated with climate change coupled with more

prevalent state and private property regimes have served to exacerbate tensions between the Dogans

and Fulani.

Small Island Developing States

The loss of sovereignty and sovereign rights in small island developing states (SIDS) is a third

example of the impact of climate breakdown on human security through sea level rises. SIDS are home

to 65 million people living on island groups made up of 38 United UN Member States and 20 Non-UN

Member/Associate Members that are located in three regions: the Caribbean; the Pacific; and the

Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean and South China Seas. They are particularly exposed to hazards such as sea-level rise, tropical cyclones, marine heatwaves, and ocean acidification, all of which are

projected to intensify as global temperatures increase 24

THE NOOSPHERE: AN EVOLUTION TOWARDS SUSTAINABILITY WITH NATURE AND THE COSMOS

The Anthropocene, as an era, may soon equate to an insignificant fraction in the evolution of the

cosmos. I have argued that our current governance model is resulting in outcomes that are leading

to the destruction of the ecosystem. The implications for life as we know it on earth are catastrophic. That said, many have argued that technology in areas such as renewable energy and other decarbonisation opportunities will mitigate the worst impacts of climate change. However, the deteriorating trends (articulated above) suggest that such a future requires a broader, more integrated, connected, and comprehensive institutional approach. An approach that incorporates principles around sustainable development; principles we so far have failed to embrace. Quantum entanglement and non-locality connectedness challenge classical notions of reality that cannot be explained; supporting a need for a more inclusive interdisciplinary dialogue beyond just science. While science seems to encourage an open and, to some degree, growing mindset, religion in the main has remained in the doldrums clutching outdated doctrine with a largely closed mindset. Consequently, while technology has connected us around the earth, our planetary spirit remains fractured with institutions struggling to keep pace with the rapid rise of technology, the politicisation of religion, and the impact of globalisation on both individuals and society. A science community that is satisfied to say what is, yet reticent to consider what ought to be, is also culpable. This missing values element, at the heart of so many of the challenges facing civil society, is inextricably linked to consciousness. While religion is fundamental to consciousness with a form-giving energy of wholeness, its reticence to fully embrace evolution allows the separation with the world of science and technology to grow.

Probably the most influential classification of how to relate science and religion has been developed by Ian Barbour25 who proposes a fourfold classification; conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration. Ilia Delio argues that the most useful perspective is one of integration noting how some like Teilhard saw computer technology as a potential means to a new level of consciousness called the noosphere or “mental sphere”, where humans could be more united and more unified by the attracting force of energy he called love. Teilhard, who died in 1955, would not have known how connected the world was to become through the world wide web, the internet of things and artificial intelligence. That said he

clearly had a sense of what could happen. He predicted that increased communications would “link us

all in a sort of ‘etherised’ universal consciousness” and that someday “astonishing electronic

computers”26 would provide mankind with new tools for thinking. Teilhard suggested a ‘giant human

organism’ would evolve giving rise to even greater complexity with a blossoming of the noosphere in a form of super- consciousness. He argued that the noosphere as the next phase of human evolution brings together the geosphere (inanimate matter) and biosphere (biological life) growing towards an even greater integration and unification, culminating in the Omega Point, merging nature, human consciousness, love and God in the future. Delio and others suggest that this deepening of humanity through a new level of global consciousness is essential for the forward movement of evolution into a sustainable future. With a rise in ultra-humanity through a consciousness of our ‘interbeing,’ an awareness that we are not separate, but part of the ecosystem, part of one large interweaving of life becomes normalised as a new purpose. In such a state, society will ensure the ecologically acceptable influence of humankind on nature and the rationalisation of human needs. It is this paradigm through which we could address the challenge of climate change.

Drawing on these concepts, Ilia Delio’s The Unbearable Wholeness of Being provides us with an extraordinary reflection on which to think about the future. Delio says “[w]e all have a part to play in this unfolding Love; we are wholes within wholes; persons within persons; religions within religions. We are one body, and we seek one mind and heart so that the whole may become more whole, more personal and unified in love.”27 By embracing the concept of the noosphere at this critical point in human existence I make the case for a reframing of how the climate and biodiversity crisis, and indeed growing regional security crisis, are viewed.

Positively, the Anthropocenic paradigm, with all its shortcomings, has also given rise to conditions that may enable final fusion of the noosphere. Shoshitaishvili argues that by building on our recognition of the divergent paradigms of the anthropocene and the noosphere we can begin the essential process of reconciling them and thus developing steady global perspectives on uncertain worldwide change.28

LEADERSHIP AS A DRIVER FROM THE ANTHROPOCENE TO THE NOOSPHERE AND GREATER SECURITY

Notwithstanding the grave security challenges and sense of regression already described, and accepting that there are identified constraints such as cyber interference, and the inconsistent access to the internet; key tenets of the noosphere have already started.

These include the deepening of humanity towards ultra-humanity; a new level of consciousness; greater unity and unification in love; and a new evolutionary stage in the development of the biosphere. What is unclear however is how, against the backdrop of the existential climate and biodiversity threats emerging, can momentum towards the new level of consciousness be progressed in a manner which enables acceleration of the balancing of human and nature interactions.

Progress towards the noosphere as the next phase of human evolution requires leadership, mobilising civil society, market and government social systems not just nationally but also at a global scale. It also requires leveraging the technological base to the maximum, something every single individual can do. Similarly, at state level, Ireland and its institutions can contribute to that leadership recognising that ultimately this leadership must be dispersed across a multilateral framework leveraging Global Citizenry29

institutions. Ireland’s social systems have a charisma that underpins a reputation for doing good.

A reputation that is inextricably linked with values, values that have been forged in a furnace of famine, migration and more.

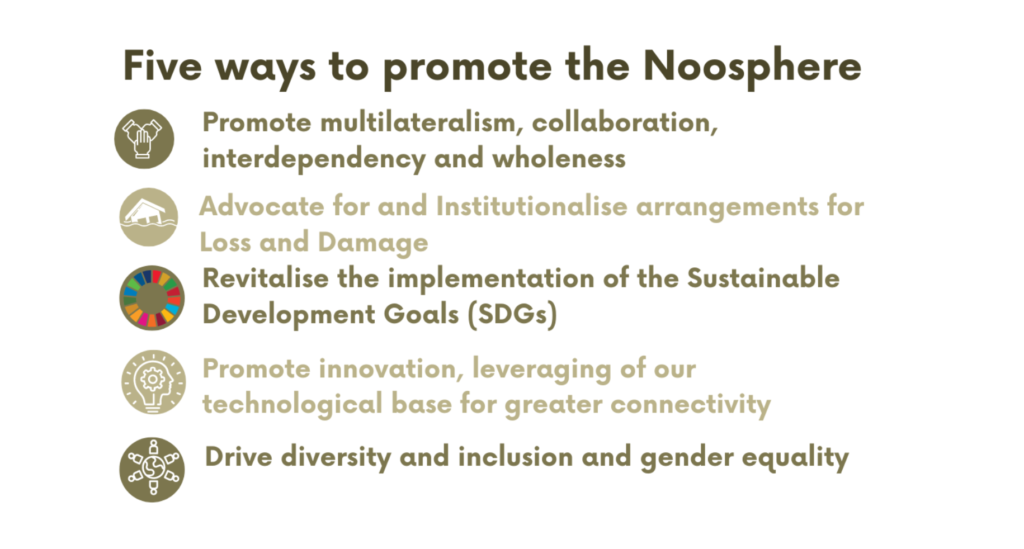

Here I propose five key ways in which the realisation of the noosphere might be advanced:

Promote Multilateralism and Collaboration as a Means for Wholeness.

Four hundred years ago, the English poet John Donne in For whom the Bell Tolls wrote, “[n]

o man is an island, entire of itself.”30 Donne’s key message is that we are interdependent in so

many ways. Today, in a world of massive change and knowledge generation, when we are physically

experiencing the effects of climate breakdown, we have never been more interdependent. Either we

will go into the future together, or we will die together in a desert of our making. Nobody and no

country can be neutral in the face of the existential threat facing us. Ireland can play a pivotal role, providing appropriate leadership, for example, integrating differing religious perspectives and encouraging a new dialogue between science and religion.

Advocate For and Institutionalise Arrangements for Loss and Damage

One of the greatest perversities associated with the extreme impacts of climate change is that many

of the communities least responsible for climate change bear the greatest impact from its effects.

Ireland has experience in the Mediterranean migrant crisis treating symptoms of migration. Mitigation and adaptation at source reduce the risks of forced irregular migration through, for example, loss and damage arrangements. Ireland’s competency in setting the agenda in this area was established by Minister Eamon Ryan and his officials who shaped the outcomes of the 27th UN Climate Conference (COP27) helping establish a new loss and damage fund (LDF). COP28 built on this with the operationalisation of the fund, receipt of several pledges and more with secretarial support from the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Key aspects of the LDF include locating the fund in the World Bank for at least four years with an aspiration for pledges to exceed $1 trillion by 2050.31 Initiatives such as the LDF provide a path for the deepening of humanity towards ultra-humanity.

Revitalise Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs are fundamental to the framework for humanitarian action and have remarkable potential as tools for accelerating convergence towards the noosphere. The fact that such platforms exist offers encouragement for the SDGs and an opportunity to expand utility to accelerate towards the noosphere.

Promote Innovation and Leveraging of our Technological Base for Greater Connectivity

Earth’s history points to five mass extinction events of biological organisms. When we think of the last two in particular, most will agree that the reptiles and dinosaurs were not responsible for their demise, they did not know they were about to become extinct and even if they did, they could not have done anything about it. The noosphere recognises that humans are different with an extraordinary intelligence driving the growth in automation, robotics, internet of things and artificial intelligence. Innovation and artificial intelligence must be nested within a values- based structure that bridges the religion science

divide while stimulating positive change, demanding new ways of thinking.

Drive Diversity, Inclusion and Gender Equality

Key to a new dialogue between science and religion is a need to continue to lead in diversity, inclusion and gender equality across many levels. Advocacy for inclusivity and equity between the sciences, religions as well at the levels of government, civil society and market levels all require a greater sharing of wealth and technology transfer in line with the institutions of the LDF. Humanitarian and peacekeeping efforts should be actioned in a comprehensive and integrated manner seeking to mix state with enterprise, higher education institutions and civil society actors. One of the strongest indicators of intra- and inter- State violence is the gender gap. Mitigating and eliminating the gender gap across key areas such as education, religion, politics and employment is fundamental to accelerating towards the noosphere.

CONCLUSION

Delio points out that for so long we have kept love outside the limits of nature, as if it is a peculiarly human emotion. While it is easy to be annoyed by love-talk, during which precious time is being wasted with sentimental silliness, “[y]et, apart from love we are not at home in the cosmos – literally.”31 Love, however, must be viewed as the very energy that attracts, from quarks and leptons at the beginning of the cosmos to this very day where complexification creates greater connectedness. At every level, we

all must strive for a more comprehensive understanding of love while striving for greater wholeness

recognising interdependencies. Understanding love as God consciousness, a love that generates new life, urging cosmic life towards greater unity in love is a fundamental characteristic of the noosphere, while bridging the gap between religion and science.

We live in an extraordinary time where the rate of change on so many fronts, including climate and

security, is akin to what one experiences in wartime and yet we try to act as if we are at peace. Clausewitz said, in war “everything is simple, but even the simplest thing is difficult.” It is a time for courageous leadership at every level from citizen to global citizenry, social institutions across state, regional and intergovernmental levels. The SDGs need to be revitalised. Diversity, inclusion, gender equality and associated values together with multilateral frameworks must be codified, actioned and recognised so that civil society and market organisations together with states promote wholeness. Equity and justice must be promoted in frameworks such as LDF.

Much that underpins our social institutions has been rooted in religion, today however this has been replaced by technology and AI with nobody really at the helm and a market driven ethos failing to tell the ecological truth driving ecological collapse. There remains an extraordinary opportunity to bridge the science religion gap, accelerating consciousness, interbeing and the noosphere as appropriate institutions are enabled with a more holistic sense of the evolution of the cosmos. This requires partnering, collaborating and multilateralism, unlocking our unprecedented knowledge. George Bernard Shaw said, “we are made wise, not by the recollection of our past, but by our responsibility for our future.”32 Internalising human love within nature requires a more sophisticated understanding of how love, as an attracting energy, enables wholeness, helping eliminate externalities. The eyes of the future are looking back at us and they are praying that we see beyond our time and strive for a love of nature built on a wholeness that is cosmos centric. Where norms like sustainability underpin a consciousness and a transcendental vision of God, a coming of God in the future as we evolve towards the Omega Point. A point where greater convergence of science and religion, revitalised spirituality and our place as part of the ecosystem, where our security is further strengthened in the reality we call nature.

- This is widely attributed to Pierre Teilhard de Chardin for example in: Robert J. Furey, The Joy of Kindness (Crossroads, 1993), 138. ↩︎

- Philip Hefner, The Human Factor: Evolution, Culture, and Religion (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1993) ↩︎

- Ilia Delio, The Unbearable Wholeness of Being: God, Evolution and the Power of Love (New York: Orbis Books, 2013) ↩︎

- World Commission on Environment and Development, Our Common Future (Oxford University Press, 1987) ↩︎

- Guardian Nigeria, “UNGA 78: Only 15% of SDGs Targets Are on Track, Says UN,” The Guardian Nigeria News – Nigeria and World News, September 18, 2023, https://guardian.ng/news/unga-78-only-15-of-sdgs-targets-are-on-track-says-un/. ↩︎

- Robert Kagan, The Jungle Grows Back: America and Our Imperilled World (New York: Knopf, 2018) ↩︎

- Jeremy Hance, “Could Biodiversity Destruction Lead to a Global Tipping Point?,” The Guardian, January 16, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/radical-conservation/2018/jan/16/biodiversity-extinction-tipping-point-planetary-boundary. ↩︎

- Ciara Murphy, ‘Rewilding: Biodiversity’s Ability to Heal,” Working Notes 37, no.1 (2023):30 – 39. ↩︎

- Geosphere subcomponents: lithosphere (solid Earth), atmosphere (gaseous envelope), hydrosphere (liquid water), and cryosphere (frozen water). ↩︎

- Rosamunde Almond et al, Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature positive society (Switzerland:WWF, 2022) ↩︎

- Caspar A. Hallmann et al., “More than 75 Percent Decline over 27 Years in Total Flying Insect Biomass in Protected Areas,” ed. Eric Gordon Lamb, PLOS ONE 12, no. 10 (October 18, 2017): e0185809, https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185809. ↩︎

- IPCC Working Group II Sixth Assessment Report Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – WGII Summary for Policymakers Headline Statements. (IPCC, 2022), https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/resources/spm- headline-statements/ ↩︎

- Naomi Foley, Tom van Rensburg and Claire W. Armstrong, The Irish Orange Roughy Fishery: An Economic Analysis (The Socio-Economic

Marine Research Unit (SEMRU), National University of Ireland, Galway, 2010) https://www.universityofgalway.ie/media/researchsites/semru/ files/10-10.pdf ↩︎ - “Global CO2 Emissions by Year 1940-2023,” Statista, accessed August 14, 2024, https://www.statista.com/statistics/276629/global-co2- emissions/. ↩︎

- Robert Monroe, “The Keeling Curve,” The Keeling Curve, accessed August 14, 2024, https://keelingcurve.ucsd.edu. ↩︎

- Colin J. Carlson et al., “Climate Change Increases Cross-Species Viral Transmission Risk,” Nature 607, no. 7919 (July 2022): 555–62. ↩︎

- Klaus von Grebmer, et al., 2023 Global Hunger Index: The Power of Youth in Shaping Food Systems. (Bonn: Welthungerhilfe, 2023) https://www. globalhungerindex.org/pdf/en/2023.pdf ↩︎

- World Economic Forum, The Global Risks Report 2023 18th Edition. (World Economic Forum: Cologny/Geneva Switzerland, 2023) https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risks_Report_2023.pdf ↩︎

- “Water Wars: How Conflicts over Resources Are Set to Rise amid Climate Change,” World Economic

Forum, September 7, 2020, https:// www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/09/climate-change-impact-water- security-risk/. ↩︎ - “Water Conflict Chronology Timeline List,” accessed August 14, 2024, http://www.worldwater.org/conflict/list/. ↩︎

- James E Hansen et al., “Global Warming in the Pipeline,” Oxford Open Climate Change 3, no. 1, January 1, 2023. ↩︎

- Renée Cho, “Climate Migration: An Impending Global Challenge”, State of the Planet, May 13, 2021, https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/05/13/climate-migration-an-impending-global-challenge/. ↩︎

- IPCC Working Group III, Mitigation of Climate Change – WGIII Summary for Policymakers Headline

Statements. (IPCC, 2022), https:// www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_ SummaryForPolicymakers.pdf ↩︎ - Adelle Thomas et al., “Climate Change and Small Island Developing States,” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 45, no. Volume 45, 2020 (October 17, 2020): 1–27. ↩︎

- Ian G. Barbour, Religion in an Age of Science, (San Francisco: Harper, 1990). ↩︎

- David Ronfeldt and John Arquilla, “Origins and Attributes of the noosphere Concept,” Whose Story Wins (RAND Corporation, 2020), https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep26549.9. ↩︎

- Ilia Delio, 2013 ↩︎

- Boris Shoshitaishvili, “From Anthropocene to noosphere: The Great Acceleration,” Earth’s Future 9, no. 2 (2021). ↩︎

- Department of Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science, Global Citizens 2030 Ireland’s International Talent and Innovation Strategy, (Dublin: Government of Ireland, 2024). ↩︎

- John Donne, “No Man is an Island”, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, and several steps in my Sickness, 1624. ↩︎

- Ilia Delio, “2015: The Year of Love”, Global Sisters Report, December 13, 2014

https://www.globalsistersreport.org/column/speaking-god/ spirituality/2015-year-love-17406 ↩︎ - John Schwab, “Beautiful Quotes By George Bernard Shaw,” Inspiring Alley : Quotes, Thoughts & Readings (blog), May 7, 2020, https://www.inspiringalley.com/george-bernard-shaw-quotes/. ↩︎