Introduction

Any discussion of prison conditions or overall prison policy in Ireland cannot but give close attention to the question of the overcrowding that is pervasive throughout the prison system.

This overcrowding starkly reflects the reality that the numbers imprisoned, both on remand and under sentence, have grown significantly over the past thirty years, with the daily average number of people in prison increasing more than three-fold, reaching well over 4,000 in 2010.

There has been an expansion in prison places – with, for example, the building of large extensions to many prisons, but the number of additional places has not matched the increase in the number of people detained. The result is that, in most of the country’s prisons, cells designed for one person now routinely accommodate two or even more people. On 7 December 2010, 63 per cent of those detained in Irish prisons – 2,762 people out of a total prison population of 4,416 – were not accommodated in a single cell.1

It is, of course, very much open to debate whether the extent to which imprisonment is being used at present is justified, either in terms of the best use of the financial resources made available by our society for dealing with people who break the law, or in terms of trying to ensure that those convicted of a crime do not re-offend. This is a fundamental issue for penal policy – but is not one that can be explored here. Instead, the concern in this article is with the possible role of international standards regarding prison conditions, and of clear benchmarks as to what may constitute acceptable levels of cell capacity, in promoting greater commitment to addressing the issue of overcrowding.

What is ‘Overcrowding’ in a Prison?

Three terms are frequently used to describe the capacity of prisons: ‘design capacity’, ‘operational capacity’ and ‘bed capacity’.2 The terms, in effect, refer to increasingly larger numbers of people being accommodated in the same space. It is possible for a prison to be overcrowded in terms of one but not another of these definitions – or to be overcrowded under all three.

‘Design capacity’ refers to the number of people a prison has been designed to detain. The planner or architect is given specific instructions and guidelines and, on the basis of these, presents a design to meet the accommodation levels requested. The specifications may follow international standards as to building regulations, fire safety, general health and safety regulations, and minimum standards regarding space. The first ‘stage’ of overcrowding occurs when the stated design capacity is exceeded.

The second category, ‘operational capacity’, is not defined by the Irish Prison Service but a useful definition may be found in the regulations of HM Prison Service for England and Wales: ‘the total number of prisoners that an establishment can hold without serious risk to good order, security and the proper running of the planned regime’ (emphasis added).3 ‘Operational capacity’ permits a greater intake of people than design capacity, yielding to the need for extra places for those sent to prison by the courts, while still recognising the inherent limits imposed by the built capacity and safety requirements. Overcrowding that occurs as a result of the operational capacity being exceeded is clearly more serious than that resulting from a breach of design capacity.

Finally, there is the notion of ‘bed capacity’ – where capacity is defined in terms of the number of beds available. In the Irish prison system, the definition of a ‘bed’ includes a single bed and a bunk bed. Capacity is limited only by the number of beds that fit in the building. A cell designed for one person may end up accommodating a bed and a bunk bed, so that the ‘capacity’ of the cell increases from one to three. In effect, the focus is on fitting the maximum number of beds into the available space with little regard for ‘the proper running of a planned regime’. While it might be considered that ‘overcrowding’ under this definition occurs when there are more prisoners than beds available, it could be argued that, in fact, a level of overcrowding is an in-built, inescapable, feature under such an approach to defining capacity.

Overcrowding in Irish Prisons

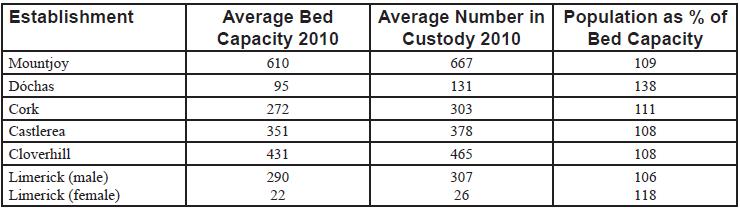

A look at six of Ireland’s fourteen prisons – Mountjoy Prison, the Dóchas Centre (for women), Cork, Castlerea, Cloverhill and Limerick – gives an idea of the seriousness of the problem of overcrowding in the system. Without considering the question of the degree of overcrowding in terms of ‘design’ or ‘operational’ capacity, it is evident that all these prisons exhibit overcrowding even at the level of ‘bed capacity’.4

Table 1: Overcrowding in Irish Prisons

As Table 1 shows, the average defined bed capacity of Mountjoy, in 2010, was 610 but there was an average of 667 people in the prison during the year; in Cork Prison, the average bed capacity was 272 but the average number in custody was 303. It is clear from Table 1, then, that each day Irish prisons are having to accommodate numbers significantly in excess of even their bed capacity. What exactly this means is not clear from the data provided. However, it is known that people in prison are placed in cells where there is no bed for them but where they sleep on a mattress on the floor; alternatively, they may be accommodated in rooms which are not designated for accommodation, and be given mattresses on the floor instead of a bed.

It is important to re-iterate how low a standard is being adopted if overcrowding is being assessed at the level of ‘bed capacity’: the assessment ought instead to be in terms of the capacity provided for by the original design of a prison, assuming this to be in line with best practice in prison design.

Implications of Overcrowding

Overcrowding has profound implications for the whole experience of being in prison. It must be remembered that, for the generality of people in Irish prisons, out-of-cell time is limited to around seven and a half hours each day, so in real terms overcrowding can mean being confined in a space originally designed for just one person which is now accommodating two or three people, for perhaps sixteen or seventeen hours out of every twenty-four.

The fact that most Irish prisons are full to capacity – or beyond – makes all the more difficult the task of dealing with feuds and threats of violence which are now a major problem within the Irish prison system, resulting in significant numbers of prisoners being deemed to require ‘protection’.

Overcrowding means there is reduced scope for moving people to different institutions where they could be safely detained without having to be locked up for their own protection for extended periods. In January 2011, there were 250 people in prison who were locked up for 23 hours or more a day. A further 250 were locked up for between 18 and 23 hours a day.5

The impact of overcrowding is felt not only in terms of the cell conditions in which people are detained but also in terms of access to facilities and services (such as education and work training). A greatly increased prison population over the past decade has not been accompanied by a corresponding increase in provision in such areas – indeed, in recent years, budgetary restrictions have resulted in cutbacks in some services.

Overcrowding is all the more problematic given the reality that a very high percentage of the people detained in Irish prisons suffer from mental illness and/or addictions.6 For such people, imprisonment inevitably imposes great difficulties – but these are compounded by enforced sharing of cramped cells.

One of the worst features of the increased incidence of double or multiple occupancy of cells is that greater numbers of prisoners are accommodated in cells which do not have internal sanitation and therefore are subjected to the degrading and unhealthy procedure of ‘slopping out’.

Moreover, double or multiple occupancy of cells means that prisoners in both cells without internal sanitation and cells with integral sanitation have to the use the toilet in the presence of others. Figures provided in a written reply to a Dáil Question show that on 17 December 2010 only 30 per cent of the 4,397 people detained in Irish prisons on that day were ‘sole occupants of a cell that has a normal flush toilet installed or have access to toilet facilities in private at all times’. Around 1,000 prisoners (22 per cent of the total) were required to slop out.7 The majority of prisoners who have to ‘slop out’ are accommodated in a shared cell.8

International Standards as Benchmarks?

Irish domestic legislation does not set down a clear minimum standard of provision which might be used as a benchmark to measure overcrowding in prisons. What guidance is provided by international standards regarding prison conditions?

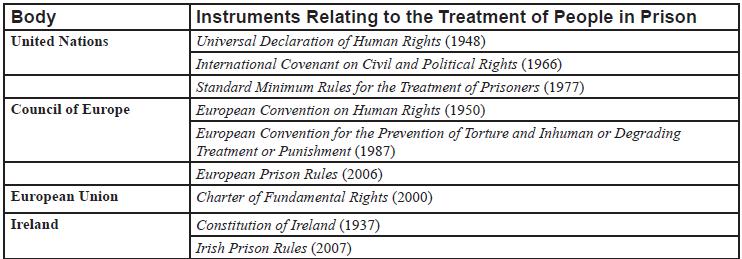

Several international agreements or covenants deal with the rights of people who are in prison and the responsibilities of States which have ratified these agreements to ensure that these rights are upheld. As a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, and the European Union, Ireland has signed up to a range of agreements touching on prison conditions, which have been drawn up by these international bodies.

Article 10 of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners states:

All accommodation provided for the use of prisoners and in particular all sleeping accommodation shall meet all requirements of health, due regard being paid to climatic conditions and particularly to cubic content of air, minimum floor space, lighting, heating and ventilation. (Emphasis added.)

In neither this nor in other international instruments is a specific figure given to indicate what is considered an acceptable minimum amount of space to be provided for each prisoner. The European Prison Rules adopted by the Council of Europe give only a fluid guide, stating in Article 18:

The accommodation provided for prisoners, and in particular all sleeping accommodation, shall respect human dignity and, as far as possible, privacy, and meet the requirements of health and hygiene, due regard being paid to climatic conditions and especially to floor space, cubic content of air, lighting, heating and ventilation. (Emphasis added.)

However, the Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT), the Council of Europe body which has responsibility for visiting countries which are signatories to the Council’s European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, has adopted as a ‘rough guideline’ the criterion that cells should be 7 square metres (‘2 metres or more between walls, 2.5 metres between floor and ceiling’).9

Table 2: Some Instruments Relating to the Treatment of People in Prison

Ireland’s Prison Rules 2007 do not set out in specific terms the minimum space to be provided for people in prison but instead lay down general standards:

The Minister shall, in relation to a prison or part of a prison, certify that all such cells or rooms therein as are intended for use in the accommodation of prisoners are, in respect of their size, and the lighting, heating, ventilation and fittings available in the cells or rooms in that prison or that part, suitable for the purposes of such accommodation.10 (Emphasis added.)

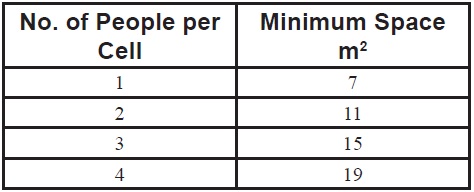

Given the apparent vagueness regarding what might be an agreed minimum floor area available for each person detained in a prison, and the consequent floating definitions of overcrowding, it is significant that in 2010 Ireland’s Inspectors of Prisons, Judge Michael Reilly, made specific recommendations regarding the space to be provided for each prisoner. In a report on the ‘duties and obligations owed to prisoners’, which he described as a ‘road map for our prisons which will ensure that we, as a country, adhere to our obligations’,11 Judge Reilly proposed the following minimum requirements for the size of cells:

- Single occupancy cells: these should be at least 7m2 in size, ‘with a minimum of 2m between walls’. Moreover, in-cell sanitation should be provided and ‘it would be preferable’, that the sanitary facilities be screened off from the rest of the cell.

- Multi-occupancy cells: In addition to the basic cell size of 7m2, there should be an extra 4m2 for each additional prisoner. Furthermore, in the case of multi-occupancy cells, ‘there must be in-cell sanitation which, in all cases, must be screened’.12

Table 3: Minimun Size of Prison Cells: Recommendations of the Inspector of Prisons.

The Inspector of Prisons states that in arriving at recommendations regarding the minimum acceptable size of prison cells he had ‘regard to’ the following:

… the Irish Constitution, our domestic laws and jurisprudence, the International Instruments that bind our country, the various reports of the CPT, the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, International Rules that refer to prisoners, the European Prison Rules, the Irish Prison Rules, Standards for the Inspection of Prisons in Ireland, best practice and my observations of prisons.13

The Inspector of Prisons turns to the European Court of Human Rights to support his proposals regarding cell size, and quotes from the decision in Kalashnikov v Russia (2002):

… the Court recalls that the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (“the CPT”) has set 7m2 per prisoner as an approximate, desirable guideline for a detention cell.14

The Inspector suggests that this clear and precise minimum standard has permitted the European Court of Human Rights to take the view that overcrowding per se amounts to a violation of Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights, as decided in Orchowski -v- Poland.15

While the setting of minimum standards by the Inspector of Prisons is a significant development, it is important to note the limitations of the proposals.

The most serious is the apparent acceptance of the continued use of multi-occupancy of cells. Over the past number of years, as plans emerged in relation to the development of a new prison at Thornton Hall, in North County Dublin, it has become apparent that the Irish Government and the Irish Prison Service have come to view multioccupancy as an ‘acceptable’, in-built, feature of prison development – no longer being seen as just an unfortunate outcome of the increasing overcrowding in Irish prisons.16 The principle of having single cells as the desired norm has apparently been abandoned. It is particularly disappointing that the Thornton Hall Review Group, established by the current Minister for Justice, Alan Shatter TD, accepted this approach: in its Report, published in July 2011, the Group recommended that: ‘the design of the prison should provide for 300 cells capable of accommodating 500 prisoners’.17

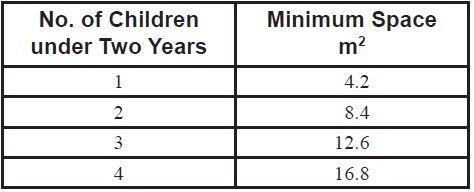

It should be noted also that in reality the minimum capacity proposed in the Inspector’s report would still mean a very limited amount of space for people who are locked up for more than half their waking hours. This is highlighted if we consider the Regulations, provided under Statutory Instruments, which are now in place in Ireland regarding the minimum ‘floor space’ to be made available to children being cared for outside their homes in pre-schools.18 The Explanatory Guide to the Regulations outlines the space requirements concerning facilities for rest and play: ‘If the sleep area for babies and children aged under 2 years is accommodated in the baby room, the overall space measurement of the baby room will then be 4.2 sq metres per child.’19

Table 4: Minimun Space Requirements under Pre-School Regulations

The fully grown person who is imprisoned might be five times the size of a child under two years of age. Furthermore, the person detained does not have a space outside the prison to which he or she returns every evening. If a baby who sleeps for only a couple of hours in a day at pre-school must be provided with a minimum of 4.2 sq metres per child for sleeping, as well as extra play space, then it could be suggested that an adult in confined conditions such as prison needs much more space and at a minimum twice the space requirement of a baby. Using this optic, the minimum space requirement for every person in places such as prisons would be 8.4 square metres. In effect, this approach would not permit a smaller space allocation per individual when more than one person was being detained in a shared cell.

Decisions of the Irish Courts

Irish courts have recognised that people in prison have rights (The State (C) v Frawley [1976]) and have underlined specific rights – the right to bodily integrity; the right of the person detained not to have his or her health exposed to risk or danger; the right not to be exposed to inhuman or degrading treatment.

However, actions by prison authorities must be glaringly wrong before any court considers it reasonable to criticise or condemn them. The possibility, held out by the decision in the 1976 Frawley case, that the courts might became a vehicle for defending the rights of people in prison was soon smothered. Just four years later, in The State (Richardson) v Governor of Mountjoy [1980], the court held that: ‘the prison authorities must be allowed a wide area of discretion in the administration of the prisons in the interests of security and good order’.20

It is clear that, thirty years on from that decision, this ‘wide area of discretion’ still applies in cases relating to prison conditions. In Mulligan -v- Governor of Portlaoise [2010], concerning the continued use of ‘slopping out’, the High Court readily accepted that this procedure is ‘repugnant by today’s standards’.21 However, it refused to accept that Mr Mulligan’s human rights had been breached. The court considered that it had to take account of the ‘overall conditions’,22 the ‘cumulative effects’23 and the ‘totality of circumstances’24 – and thereby even the repugnant becomes acceptable in the eyes of the court.

In Ireland, it is the Constitution which provides the fundamental law to be applied in the courts. Article 29.6 of the Constitution explicitly limits the extent to which international treaties may apply within the State: ‘No international agreement shall be part of the domestic law of the State save as may be determined by the Oireachtas’. (Emphasis added.)

The enactment of the European Convention on Human Rights Act 2003 introduced the European Convention of Human Rights into domestic Irish law. However, Chief Justice Murray, in McD. -v- L. & anor [2009] IESC 81, has set out in clear terms the limits on the application of the European Convention, and of the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights, in Ireland, relying on the provisions of Article 29 of the Constitution to support his position.

Early in his judgment he states:

… I think it is clear that the Convention is not directly applicable as part of the law of the State and may only be relied upon in the circumstances specified in the European Convention on Human Rights Act of 2003. (Emphasis added.)

He adds:

The European Convention may only be made part of domestic law through the portal of Article 29.6 and then only to the extent determined by the Oireachtas and subject to the Constitution. (Emphasis added.)

Furthermore, he states that the provisions of the Constitution mean that: ‘An international convention cannot confer or impose functions on our Courts’. He goes on to say:

Of course the Courts may be given jurisdiction to enforce or adjudicate on rights which the State has agreed, in an international treaty, to promote or protect. But it can only be conferred by national law and if sought to be done by making an international agreement, wholly or partially, part of domestic law then it must be done in accordance with Article 29.6 and in a manner consistent with the Constitution as a whole.

Given the reluctance on the part of the courts to meddle in the administration of the prison system, and the serious limitations on the application of relevant international treaties which Ireland has ratified, it seems prudent to recall the recommendation of the authors of a book on Irish prison law, published thirty years ago:

… the appropriate place to seek alterations or complete changes in these areas is not in a Court but through the Oireachtas. The function of the Judiciary is to interpret the law as it is, not as it ought to be.25 (Emphasis added.)

The courts walk a fine line between applying the law and making the law. In matters concerning prison law, the courts in Ireland seem to have taken the most cautious of approaches, trying not to trespass in any way on the role of the Oireachtas as the law-maker.

Conclusion

In the light of the restrictions on the courts as law-makers, of the requirement that they respect and uphold administrative decisions unless these are clearly in error, and the restriction imposed by the Constitution at Article 29 as regards the application of international human rights treaties, it seems clear that there is limited scope for a legal route towards expansion of the understanding of prisoners’ rights in Ireland.

However, the coming into force of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights could result in a situation whereby Irish courts may be obliged to follow the jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice of the EU, which is binding on Irish courts in matters of EU competence. It remains to be seen how Court of Justice decisions may affect Irish jurisprudence in relation to human rights, including the rights of EU citizens in Irish prisons.

In the meantime, given the gap between the desired treatment of people in prison and the actual conditions, there is much work to be done to persuade the public and politicians as to the necessity of change. Advocacy must attempt to influence not only the minds but also the hearts of those who can bring about change. The success of this advocacy depends on the whole institution of law-makers – the legislature, the judiciary, the executive and an informed public. Without this last element, the ‘established’ tripartite structure of law-makers (the legislature, the judiciary, and the executive) will continue to flounder in that crevice between how we actually house people detained in our prisons and the desire to uphold international standards in regard to prison accommodation.

Notes

1. See written reply on 8 December 2010 by the then Minister for Justice and Law Reform, Dermot Ahern TD, to a Dáil Question by Ciarán Lynch TD.

2. I am grateful to Fr Peter McVerry for his outlining of these categories.

3. HM Prison Service, Prison Service Order – 1900 Certified Prisoner Accommodation of 8 August 2001. ‘Operational capacity’ is often used with reference to other public buildings such as schools and offices: buildings are often modified, after they go into use, to accommodate changed conditions and needs.

4. Data from Irish Prison Service, Annual Report 2010, Longford: Irish Prison Service, 2011, Table 2.7, p. 13.

5. Written reply on 27 January 2011 to Dáil Question by Ciarán Lynch TD (information relates to 26 January 2011).

6. See for example, H.G. Kennedy et al, Mental Illness in Irish Prisoners: Psychiatric Morbidity in Sentenced, Remanded and Newly Committed Prisoners, Dublin: National Forensic Mental Health Service, 2005.

7. Written reply by the then Minister for Justice and Law Reform, Dermot Ahern TD, on 27 January 2011, to a Dáil question by Ciarán Lynch TD.

8. Judge Michael Reilly, Inspector of Prisons, The Irish Prison Population – An Examination of Duties and Obligations Owed to Prisoners, Nenagh: Office of the Inspector of Prisons, July 2010, par. 3.19, p. 20. (www.inspectorofprisons.gov.ie)

9. CPT, 2nd General Report on the CPT’s Activities Covering the Period 1 January to 31 December 1991, Strasbourg, CPT/Inf (92) 3 [EN], 13 April 1992. (www.cpt.coe.int/en/docsannual.htm)

10. Prison Rules 2007, n. 18.1, p. 21.

11. Judge Michael Reilly, Inspector of Prisons, op. cit.

12. Ibid., par. 2.3, p. 10.

13. Ibid., par. 2.4, p. 10.

14. Council of Europe, European Court of Human Rights, Kalashnikov v. Russia (Application no. 47095/99), Judgment, Strasbourg, 15 July 2002 (http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/416bb0d44.html ), quoted in Judge Michael Reilly, op.cit., par. 2.8, p. 13.

15. Council of Europe, European Court of Human Rights, Orchowski -v- Poland (Application no. 17885/04), Judgment, Strasbourg, 22 October 2009, Final 22/01/2010. (http://cmiskp.echr.coe.int/tkp197/view.asp?action=html&documentId=856497&portal=hbkm&source=externalbydocnumber&table=F69A27FD8FB86142BF01C1166DEA398649)

16. See Press Release from the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice in response to comments on single cells by Dermot Ahern TD, Minister for Justice, 28 July 2010 (www.jcfj.ie/news).

17. Report of the Thornton Hall Project Review Group, July 2011, p. 16 (www.justice.ie). See comment on the Review Group Report by the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice, ‘Inadequate Prison Conditions now Cemented in Policy of the New Government’, Press Release, 29 July 2011 (www.jcfj.ie/news).

18. Child Care (Pre-School Services) (No 2) Regulations 2006 (Statutory Instrument S.I. No. 604 of 2006) and Child Care (Pre-School Services) (No 2) (Amendment) Regulations 2006 (Statutory Instrument No. 643 of 2006).

19. See ‘Regulation 28: Facilities for Rest and Play’ in the ‘Explanatory Guide to Requirements and Procedures for Notification and Inspection’ regarding Child Care (Pre-School Services) Regulations.

20. The State (Richardson) v Governor of Mountjoy [1980] ILRM 82.

21. Mulligan v Governor of Portlaoise Prison & Anor [2010] IEHC 269, par. 14.1. (http://www.courts.ie/Judgments.nsf/09859e7a3f34669680256ef3004a27de/70edce35d14d515a80257761003be166?OpenDocument)

22. Ibid., par. 8.

23. Ibid., par. 129, quoting from the European Court of Human Rights decision Bakhmutsky v. Russia (Application No. 36932/02, 25th June, 2009) which specifically uses this phrase.

24. Ibid., par. 154–155; in par. 154 the court quotes from a Northern Ireland decision, Martin v. Northern Ireland Prison Service [2006] N.I.Q.B. 1.

25. Raymond Byrne, Gerard Hogan and Paul McDermott, Prisoners’ Rights: A Study in Irish Prison Law, Dublin: Co-op Books, 1981.

Patrick Hume SJ is a solicitor and works in the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice.