Deborah Burton and Dr Ho-Chih Lin

Deborah Burton is one of the co-founders of Tipping Point North South, a non-profit set up by former debt, trade and tax justice campaigners to work across both the creative and NGO sectors through campaigns, events and cinema documentary production. She leads on Tipping Point North South’s primary policy/advocacy project: Transform Defence for Sustainable Human Safety.

Ho-Chih Lin is deputy project manager and lead researcher/writer for the Transform Defence project, Prior to his involvement with TPNS social-issue documentaries and research, he trained as a quantum physicist and holds a PhD from University College London and an MSc from London School of Economics and Political Science.

WHERE WE ARE AT

Wars in Ukraine and Gaza are fuelling a new arms race. We are in a new nuclear arms race too, 1 not to mention drones, AI and space wars. We are currently spending more than $2.4 trillion on the global military, and the amounts keep rising every year. 2 At least a quarter of global military spending goes to

arms and military service companies. 3 For some countries, like top military spenders US and UK, more than half of national military spending goes to private military contractors, such as Lockheed Martin and BAE Systems. 4

The war in Ukraine has also led to NATO calling for its members to extend military budgets further to 2% or more of GDP – had this been in place between 2021 and 2028, it would have resulted in an estimated total military expenditure of $11.8 trillion and a collective military carbon footprint of 2 billion metric tonnes of CO₂ equivalent (tCO₂e). 5 In other words, totally incompatible with climate targets and net zero.

Unless we change course, in the six years to 2030, the global military will receive more than $14 trillion while necessary climate finance to achieve the UNFCCC 2030 targets remains severely underfunded. At

the moment, public climate finance − all government expenditure on climate − was estimated globally to be less than one sixth of military spending.6 As for the pledge by the developed countries under the Paris Agreement to finance climate actions in developing countries, the ratio is even worse. The richest countries (categorised as Annex II in the UN climate talks) are spending ($7.3 trillion between 2013 and 2020) 30 times as much on their armed forces as they spend on providing climate finance ($243.9 billion) for the world’s most vulnerable countries.7

But some, including the arms industry and its lifeblood, the oil industry, are more than happy with this status quo, making obscene profits while polluting and destroying the only habitat we have. The top 100 arms companies in the world made $592 billion in arms sales in 2021, the year before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The top 20 alone accounts for two thirds of the total and come from just a handful of countries: US, China, Russia, UK, France and Italy. The global military carbon footprint, including emissions from both the military and the arms industry (but excluding emissions from conflict or post-conflict reconstruction), is estimated to be 5.5% of annual global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, more than

emissions from civilian aviation and shipping combined.8

THE WORLD IS AT THE TIPPING POINT

Nearly all past and present IPCC climate scientists now believe the Paris Agreement’s 1.5oC target will not be met and almost half believe the average global temperatures will rise to at least 3oC above pre industrial levels this century. 9 Even the head of UNFCCC, a rather conservative organisation by its track record, issued an urgent warning in early 2024 that humanity has two years left to ‘save the world’. 10

It is not the ‘averages’ that damage or even destroy a society. Rather, it is the frequency and intensity of ‘extremes’ that can destroy a civilisation. Even at 1.5oC of heating, which the world is currently experiencing,11 the climate extremes are making many places in the world (especially in the global south) inhospitable, whether by unprecedented and prolonged flooding, heatwaves or drought. Professor Tim Lenton, the world’s leading expert on planetary tipping points, warned, “if we carry on the way we are going, I can’t see this civilisation lasting the end of this century.”12 When global heating exceeds 3oC, the physical laws of thermodynamics lead us to expect that most, if not all, societies will be hit by climate extremes so hard and so frequently that there will barely be time to recover, let alone expect economic growth. Simply put, there is no meaningful local or global economy if the planet is in meltdown and humanity is left to fire-fight extreme weather. Our current fossil-fuel-driven neoliberal capitalism is – on most counts – on its last legs. Beyond 2oC of heating, the survival of our civilisation will be on the line.

OVERTURNING THE ECONOMICS OF WAR:

Why we must kickstart degrowth and place the military economy in the degrowth narrative

The world has been following alarmingly close to the trendlines predicted by the Club of Rome’s 1972 book, Limits to Growth, which pointed to an eventual collapse of global civilisation.13 We urgently need to ‘degrow’ until our economy reaches a steady state where the extraction and replenishment rates of resources are at equilibrium, bringing our society to co-exist harmoniously within itself and with nature,14and it will be too late if we do not start now. 15

Degrowth is a planned and democratic reduction of production and consumption in rich countries to lower environmental pressures and inequalities while improving people’s well-being.16 So, if all areas of human activity must decarbonise and be considered for degrowth, why are we letting the oil dependent militaries follow a different path? Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel made this point: “We can reduce resource use in rich nations quite dramatically while still meeting human needs at a high standard by scaling down forms of economic activity that are socially less crucial. SUVs, fast fashion, private jets, advertising, planned obsolescence, the military industrial complex… there are huge chunks of production that are organised primarily around corporate power and elite consumption and are irrelevant to human needs.” 17

Applying degrowth to the military means raising necessary questions about defence in this climate changing era. A post-growth zero-carbon world demands we reduce military spending to sustainable levels and fully decarbonise our militaries, with less cash for their big-ticket hardware, overseas bases, war and, by extension, much fewer emissions. This is not about delivering ‘green ways to conduct war’- weaponry and war will always kill living beings, will always destroy and pollute environments. Instead, this is the starting point for much needed, if challenging, discussions that can lead us to a paradigm shift in geopolitics.

The IPCC 2022 ‘Mitigation of Climate Change’ report offers up routes to degrow the economy: avoid (by consuming less), shift (by substituting one for another), and improve (by greening the existing).18 We applied this model to the military economy.19

Avoid locking into expensive and gas-guzzling weapon systems. While the imperative now is to avoid retail therapy and civilian flights, the global military has a free pass to buy and operate as many big-ticket gas guzzlers (e.g., F-35s and Eurofighter Typhoons) as it wants, with no questions asked by politicians. When the whole world is expected to reach carbon net-zero by 2050, isn’t it absurd that the F-35 will still be the backbone of the US Air Force (and many other national air forces) at that time, flying above and laughing at us at a rate of 1 tCO₂e per 80km?20

Avoid military aggressions. After the humanitarian (and climate) disasters of invasions by some of the top military spenders into Iraq, Yemen, Ukraine and Gaza, to name but a few in recent times, wars are incompatible and an ‘absurdity’ in the new zero-carbon world. 21

Substitute “great power competition” with “non-offensive defence”. Defence should be about our collective human safety, not power projection and exploitation. Whichever nationality, friend or foe, we all share the same planet we call home. Cooperation is the only way forward for humanity to deal with the climate crisis.

Substitute the defence industry with the green economy. Many skills in the high-tech defence industry are interchangeable with those required by the clean-energy industry. The continued growth of weapon production will only lead humanity to doom, either before or during full-on climate chaos.

Improve (by electrifying) the existing defensive weapons while gradually getting rid of offensive weapons, including nuclear weapons. We may never be able to get rid of all offensive weapons but if we are well protected by defensive weapons, isn’t it reasonable to expect sometime in the zero-carbon future that we should start the conversation around how few offensive weapons we actually need to not just to feel safe but be literally safe?

Improve our (energy, transport and health) infrastructure to make them more resilient to crises and disasters in the understanding that when human safety is protected, it follows that national security is also secured.

Green New Deals are an expression of degrowth – and the military must be a part of GND thinking because we need peaceful green prosperity

Alternative narratives to the growth agenda are encouragingly becoming mainstream; a leading idea in the US, UK and elsewhere is a Green New Deal (GND), an initiative to bring about green prosperity by transforming the economy, creating good and green jobs while at the same time tackling the climate emergency. It’s a monumental, difficult task across myriad industries and areas of human activity. Nevertheless, notably absent in present day GNG thinking is an awareness about the role of the world’s militaries and their significant (and profoundly underreported) contribution to climate change.22

Furthermore, high military spending inhibits economic and social development.

In societies with big military budgets, there is a huge dividend to be reaped if there is enough political will to take the military into account in the GND and convert a significant part of the arms industry to other socially and environmentally beneficial industries, such as clean tech and green energy. Current defence

policies and budgets of all major economies (primarily G20) are both socially and environmentally incompatible with the spirit of Green New Deals. Military spending is the least effective way to create jobs; for example, spending on health care, education, clean energy, and infrastructure instead of ‘War on

Terror’ would have created a net increase of 1.3 million jobs in the US.23

The $2.4tn military economy is maintained by an enormous workforce that will continue to pump substantial amounts of GHG emissions unless a GND that includes actions to cut and divert military spending is enacted This could be a major source of funds for urgently needed and under-invested areas, such as universal healthcare and the wholesale electrification of the economy. It also leads to ‘conversion’

− converting the skills of workers in the arms industry towards equally highly skilled jobs in a sustainable low carbon economy by ‘Just Transition’.24 It is estimated that, compared to the military economy, 40% more jobs would be created in infrastructure or the clean energy industry, 100% more jobs in healthcare

and 120% more jobs in education25 for the same amount of spending.

Ever-mounting evidence shows that people and the planet get far greater value for money when we scale back the fossil-fuel reliant and carbon-intensive militaries of the world and invest that money into a peaceful, equitable, green economy. Green New Deal Plus (GND Plus), an economic proposal developed by our organisation ‘Tipping Point North South’, therefore argues the need to include the military and the arms industry in all GND thinking and is a way to bring GND thinking to meet the hidden reality of military carbon footprint.26

The G7 nations (especially the UK and US) are historically responsible for disproportionate levels of GHG emissions. A GND Plus is an opportunity for the G7 and the rest of the advanced economies to convert their arms sector into a green jobs revolution domestically while also diverting their military spending to

support global climate justice − reparations for those injustices through transfers of finance and resources to support energy transitions and climate adaptation internationally.

Annual climate adaptation costs in developing countries are estimated at $70 billion.27 This figure is expected to reach $140-300 billion in 2030 and $280-500 billion in 2050. These are tiny sums in comparison to what is spent annually by the big military spenders. $70bn is 6% of what G7 spends annually on military (a ratio of 1:16) and 3% of the annual global military spending (1:30). Simply by reallocating a few cents per dollar military spend, the top spenders would have enough money to fully fund vulnerable developing countries to adapt to the climate-changed world.

Ambitious and equitable − a route to driving down military spending and redirecting to ‘human safety’ needs

The UN is calling for a climate finance increase from billions to trillions28 – it says we need $2.4 trillion every year from now on to address climate change. Global military spending is also $2.4 trillion per annum. Evidently, the money is there for militaries but not for the world’s most climate vulnerable nations, which have done absolutely nothing to create the climate chaos era we are now in. Furthermore, military spending positively correlates to military carbon footprint – the more you spend on big ticket weaponry, the more the emissions.29

We need concrete routes by which to start to reverse this climate injustice.

The Five Percent Formula proposal is a proposal to drive down military spending via a two part mechanism to achieve major, year on-year cuts to global military spending over 10 years and beyond in order to fund human safety needs and thus deliver a green peace dividend.30 It aims to get back to that

post-cold war ‘Gorbachev’ era of annual military spending of $1 trillion from the current excessive $2 trillion, and additionally to implement a ‘5% threshold rule’ linking reductions in military spending to the annual rate of change in GDP.

The first-part calls on the top 20 military spenders (who account for 85%) to cut their military spending by 5% each year for 10 years. This would see a compound cut to annual global military spending by 40% after the first decade and could deliver $960 billion in total to be redirected for human safety needs. After

the first decade, part-two of the formula kicks in as we call upon all nations to adopt the 5% threshold rule, where the % change of military spend in a given year is determined by the previous year’s rate of change in GDP, less 5 percentage points. For example, 2% GDP growth (+2%) means a 3% cut to the annual defence budget, and 1% GDP degrowth (-1%) leads to a 6% spending cut. This way, nations will sustainably degrow their military economy, such that every country reduces their military spending in a way that is faster and deeper than their overall economy.

$960bn in total savings in annual global military spending over the first decade, could be redirected to fund:31 international climate finance or global biodiversity conservation fund at $100bn p.a. for 9 years, or WHO at $2bn p.a. for 480 years, or UN disaster risk reduction at $500mn p.a. for 1920 years, or UN peacekeeping at current $5bn p.a. for 192 years.

There is certainly money available to fund critical human safety needs.

And there is one more funding source for the money pot – in addition to runaway military spending, there are excess profits made by the arms industry, it is imperative for us to have the political will to rein in it’s profiteering.

Excess profits tax on the arms industry

As we write this, the world has been witnessing Israel’s indiscriminate carpet bombing in Gaza. It is the most destructive of this century and among the worst in history with respect to the size and density of the area, the built environment and the population. So much ammunition has been used that the total

explosive yield was compared to multiple nuclear bombs on an area a quarter of the size of London but as densely populated.32 All this destruction is not possible without the ammunition supplied by Israel’s allies. Gaza, Ukraine and many other such victims of wars, be they past, present or future, have the highly

profitable global arms industry as the key enabler.

The current global military spending is a $2.4 trillion feeding trough for arms companies in a sector infamous for corruption (an estimated 40% of all trade corruption) and with scant regard for human rights.33 Arms companies, by definition, profit from the human, environmental and climate destruction of war. Moreover, many of these companies also profit by securing government contracts as part of

the militarisation of emergency response to conflict and climate disasters. Arms companies can never make good the profound cost to humanity that they have caused over many decades. But the time has certainly come to put them in the climate polluter and profiteer frame. It is time for them to pay up.

We estimate that a global excess profits tax on arms companies could deliver $30 billion dollars every year to fund international climate finance.34 In times of war, an additional punitive war profiteers’ tax could deliver considerably more. Had this war profiteers’ tax been applied in 2024 (for Ukraine and Gaza

wars), an extra $52bn would have brought the 2024 annual total to $82 billion. This tax alone would be more than four fifths of the pledged (but never fully fulfilled) $100 billion a year climate finance by developed countries to developing countries.

ALONGSIDE THE ECONOMIC ‘SYSTEM CHANGE’, WE NEED NEW THINKING ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Military power and spending has always been central to re-enforcing power, poverty, unjust distribution of resources, and economic and environmental collapse. Dr Martin Luther King’s ‘triple evils’— economic exploitation, racism and militarism — are alive and well in the 21st century. There is, and always has been, a direct correlation between military power (and spending) and economic power with the former existing to reflect and protect the latter.

Meantime, geopolitical threats – real, perceived, exaggerated or invented – will likely always be with us and it is the job of the government to defend its citizens from such threats. But climate change, habitat loss, mass species extinction and the threat of future pandemics and the attendant global economic instability (poverty and inequality) are now, collectively, overriding all other conventional ‘security’ threats and are the clear and present threats to all humanity.

These multiple and entangled threats – as ever – hit the poorest of our family members hardest. In response, our collective $2 trillion annual global ‘defence’ spending offers humanity no protection whatsoever in dealing with these threats to our collective safety. You can’t address climate change with a Trident nuclear missile or stop a pandemic with the F-35. Yet neither received the scale of funding needed for effective prevention or mitigation.

We are stuck with an out-of-date and not fit-for-purpose defence and foreign policy paradigm, reflected in excessive and wasteful global military spending.

If we accept that we need a system change to transform the economic landscape to meet the challenges of this 21st century, then we must also appreciate that we need an accompanying transformation in security, defence and ultimately foreign policy, able to fully meet the enormities of the task we face.

REPLACING THE ‘SECURITY’ NARRATIVE WITH ‘SUSTAINABLE HUMAN SAFETY’

We need to take back the narrative by replacing the loaded word ‘security’ with ‘safety’.35 Outdated notions of national security should now be replaced by the concept of ‘sustainable human safety’. The

‘peace of mind’ derived from fossil-fuel driven militarism is — on many critical counts — no longer fit for the 21st century. In its place, we need a new sustainable human safety foreign and defence framework, emphasizing collective well-being over self-centred interests and cooperation over competition.

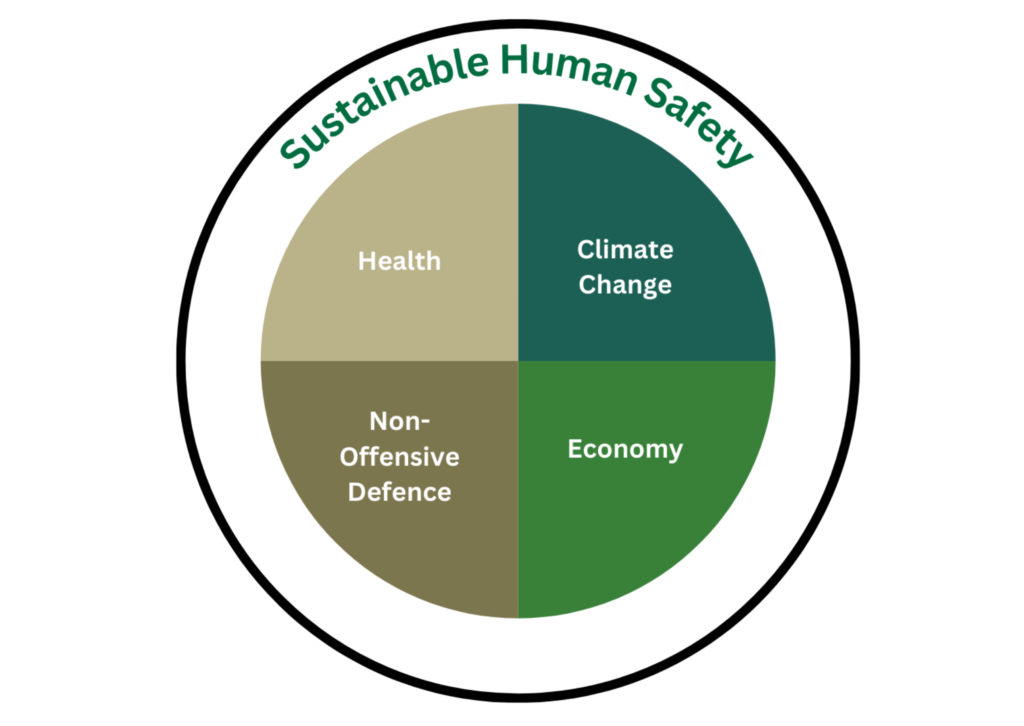

Under the sustainable human safety framework, ‘defence’ is not a standalone area that is only concerned with ‘national security’. Rather, it is but one quadrant of a whole circle, also comprising economy (eg, inequality and poverty reduction), health (pandemic prevention, well-being) and environment (climate change, biodiversity), and has the principle of ‘non offensive defence’ at its heart.

Sustainable human safety builds on the concept of ‘human security’ (introduced by UNDP in 1994) and differs from the traditional notion of defence in that it does not put ‘national security’ over all other concerns of human safety. By emphasising the interwoven linkage between economy, environment, health and defence, it forces us to take a comprehensive and systemic approach to formulate defence policies fit for the 21st century. The sustainable human safety framework ensures that defence policies do

not just look at ‘national security’ in isolation (the 20th century way).

Critically, the principle of non-offensive defence is firmly embedded in the sustainable human safety framework. Non-Offensive Defence is a defence strategy that aims to have a minimum of offensive strength while maximising defensive capability. Fundamentally, non-offensive defence focuses on defensive equipment, structure, deployment and tactics, while offensive and force projection capabilities

are minimised. Furthermore, non-offensive defence focuses on territorial defence and a contribution to an international peacekeeping and reconstruction force that can carry out UN endorsed humanitarian interventions. Under this defence framework, major offensive platforms, including the US or Russian nuclear triads, the British Trident ballistic missile system, aircraft carriers and conventional nuclear submarines would be cancelled. A new international security architecture based on global disarmament should also be actively pursued by the world’s leading powers.

COUNTERBALANCE TO THE BIG MILITARY POWERS.

Ireland, Spain and Norway’s recognition of Palestine has illustrated the efficacy of smaller nations to show moral power through ethical political action. Without, often smaller, nations acting as a counterweight to their bigger economic counterparts, international debate and decision-making – whether the UN, IMF,

World Bank or UNFCCC – is denuded of integrity.

Neutrality can also play a hugely important part in this. As a neutral country, Ireland has a proud UN history including its outstanding commitment to peace-keeping. Ireland could be the closest thing in Europe to a non offensive defence nation. In a debate about ‘the gaping gap’ in Irish air defence, a retired

senior Air Corps officer recommended instead of purchasing overpriced top-of-the-range fighters such as the F-35, the Government could invest in “light combat aircraft” providing “90 per cent of the capability of

their far more expensive cousins, at a fraction of the cost, and would provide an adequate, if limited, air policing capability.”36 Such a sensible suggestion – let alone public debate – would be close to impossible to have in any big military-spending nation, NATO members included. Ever since its inception, the F-35 has been mired with myriads of problems.37 Dubbed ‘the part-time fighter jet’ by the Project on Government Oversight, it entered service in 2015, nearly 10 years later, the fleet can still only perform its assigned missions 30% of the time.38 They went on to conclude in their analysis that the weak oversight and negligent accountability made the F-35 “the most expensive and least ready modern combat aircraft in our history.” In spite of these, according to Lockheed Martin, at least 400 of its F-35s will be delivered by 2030 to European NATO members, in addition to more than 2,000 to the US.

Compared to many other nations, Ireland is well placed to build on its much understood, respected and longstanding neutrality by going even further and developing groundbreaking, future-looking policies of non-offensive defence. Moreover, Ireland’s military spending is low and its military carbon footprint is relatively small, precisely because it lacks a strong vested interest in the military-industrial complex. Like Ireland’s position on Palestine, Ireland could lead the world again on these matters of international cooperation, human safety and investment in the things that really matter, if we are to avoid the consequences of catastrophic climate change.

In the same way we see ever more imaginative, urgent and necessary thinking on economic transformation, we need that parallel transformation in thinking when it comes to foreign and defence policy.

“What we urgently need now is a rethinking of the entire concept of security. Even after the end of the Cold War, it has been envisioned mostly in military terms. Over the past few years, all we’ve been hearing is talk about weapons, missiles and airstrikes… The overriding goal must be human security: providing food, water and a clean environment and caring for people’s health. To achieve it, we need to develop strategies, make preparations, plan, and create reserves. But all efforts will fail if governments continue to waste money by fueling the arms race… I’ll never tire of repeating: we need to demilitarize world affairs, international politics and political thinking.”

Former President of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, April 15, 2020, TIME39

Footnotes:

- François Diaz-Maurin, ‘The US and China Re-Engage on Arms Control. What May Come Next’, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (blog), 15 November 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/11/theusandchinareengage-on-arms-control-what-may-come-next/ ↩︎

- Nan Tian et al., ‘Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2023’ (SIPRI, April 2024), https://www.sipri.org/publications/2024/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-world-military-expenditure-2023. ↩︎

- Xiao Liang et al., ‘The SIPRI Top 100 Arms-Producing and Military Services Companies, 2022’, SIPRI Fact Sheet (SIPRI, December 2023),

https://www.sipri.org/publications/2023/sipri-fact-sheets/sipri-top-100armsproducingandmilitaryservices-companies-2022. ↩︎ - Stephen Semler, ‘Biden Sends Stimulus Checks to Military Contractors Instead of Ordinary People’, Substack newsletter, Polygraph (blog), 30 December 2021, https://stephensemler.substack.com/p/biden-sendsstimulus-checks-to-military. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin et al, ‘Climate Crossfire: How NATO’s 2% Military Spending Targets Contribute to Climate Breakdown’, Tipping Point North South, Stop Wapenhandel and Transnational Institute, 2023, https://transformdefence.org/publication/climate-crossfire-how-natos-2-military-spending-targetscontribute-to-climate-breakdown/; Carbondioxide equivalents (CO₂e) are a measure of the effect of different greenhouse gases (GHGs) on the climate, where other GHGs (e.g. methane) are compared to a unit of CO₂. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton ‘Stockholm+50 and Global Military Emissions’, Tipping Point North South, 2022, https://transformdefence.org/publication/stockholm50-and-global-military-emissions/ 7 Mark Akkerman et al., ‘Climate Collateral: How military spending accelerates climate breakdown’, Transnational Institute, Stop Wapenhandel and Tipping Point North South, 2022, https://www.tni.org/en/publication/climate-collateral ↩︎

- Mark Akkerman et al., ‘Climate Collateral: How military spending accelerates climate breakdown’, Transnational Institute, Stop Wapenhandel

and Tipping Point North South, 2022, https://www.tni.org/en/publication/climate-collateral ↩︎ - Stuart Parkinson and Linsey Cottrell ‘Estimating the Military’s Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions’, Scientists for Global Responsibility, https://www.sgr.org.uk/publications/estimating-military-s-global-greenhouse- gas-emissions ↩︎

- Damian Carrington, ‘World’s Top Climate Scientists Expect Global Heating to Blast Past 1.5C Target’, The Guardian, 8 May 2024, sec. Environment, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/may/08/worldscientistsclimatefailuresurveyglobal-temperature. ↩︎

- “Two Years to Save the World: Simon Stiell at Chatham House |UNFCCC,”, https://unfccc.int/news/two-years-to-save-the-worldsimon-stiell-at-chatham-house. ↩︎

- Mark Poynting, ‘World’s First Year-Long Breach of Key 1.5C Warming Limit’, BBC News, 8 February 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/scienceenvironment68110310 ↩︎

- ‘Extinction Rebellion (XR) on TikTok’, TikTok, accessed 4 June 2024, https://www.tiktok.com/@extinctionrebellionxr/video/7067669420750998789 ↩︎

- Ian Sutton, ‘Limits and Beyond: No More Growth’, Substack newsletter, Net Zero by 2050 (blog), 2 June 2022, https://netzero2050.substack.com/p/limits-and-beyond. ↩︎

- Hubert Buch-Hansen and Iana Nesterova, ‘Less and More: Conceptualising Degrowth Transformations’, Ecological Economics 205 (1 March 2023): 107731. ↩︎

- Charles Fletcher et al., ‘Earth at Risk: An Urgent Call to End the Age of Destruction and Forge a Just and Sustainable Future’, PNAS Nexus 3, no.4 (1 April 2024): page 106. ↩︎

- Timothée Parrique, ‘Sufficiency Means Degrowth’ (blog), https://timotheeparrique.com/sufficiency-means-degrowth/ ↩︎

- Jason Hickel, ‘Degrowth Is About Global Justice’, Green European Journal, January 2022, https://www.greeneuropeanjournal.eu/degrowthis-about-global-justice/. ↩︎

- Priyadarshi R. Shukla et al., eds., Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change., 2022. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, “Placing the Military in the Degrowth Narrative” 2023 Degrowth Journal, 21 August 2023. ↩︎

- To put this figure into context 1 tCO₂e would be similar to driving 5,000km in a petrol car (varies depending on type of car etc) and the emissions per capita in Ireland in 2023 was 10.4 tonnes CO₂e/person. ↩︎

- ‘Guterres in Ukraine: War Is “Evil” and Unacceptable, Calls for Justice | UN News’, 28 April 2022, https://news.un.org/en/story/2022/04/1117132. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, “Indefensible: The True Cost of the Global Military to Our Climate and Human Security’, Tipping Point North South, 2020, https://transformdefence.org/publication/indefensible/ ↩︎

- Heidi Garrett-Peltier, ‘War Spending and Lost Opportunities’, Costs of War, 2019. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2019/March%202019%20Job%20Opportunity%20Cost%20of%20War.pdf ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, ‘Military Emissions, Military Spending & Green New Deals’, Tipping Point North South, 2022, https://transformdefence.org/publication/militaryemissionsmilitaryspendinggreen-new-deals/ ↩︎

- ‘Employment Impact | Costs of War’, The Costs of War, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/economic/economy/employment. ↩︎

- ‘Green New Deal Plus’, Tipping Point North South, 19 June 2019, https://transformdefence.org/transformdefence/economics/green-new-dealplus/ ↩︎

- United Nations Environment Programme (2021). Adaptation Gap Report 2020. Nairobi, http://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gapreport-2020 ↩︎

- ‘From Billions to Trillions: Setting a New Goal on Climate Finance’, UNFCCC, https://unfccc.int/news/from-billions-to-trillions-setting-anew-goal-on-climate-finance. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin et al, ‘Climate Crossfire’. ↩︎

- ‘The Five Percent Proposal’, Tipping Point North South, 6 June 2019, https://transformdefence.org/the-five-percent-proposal/ ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, ‘Global Military Spending, Sustainable Human Safety and Value for Money’, Tipping Point North South, 2020, https://transformdefence.org/publication/value-for-money/ ↩︎

- Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor, ‘Israel Hits Gaza Strip with the Equivalent of Two Nuclear Bombs’, Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor,

https://euromedmonitor.org/en/article/5908/Israel-hits-Gaza-Stripwith-theequivalentoftwonuclearbombs. ↩︎ - A Feinstein, P Holden, and B Pace, ‘Corruption and the Arms Trade: Sins of Commission’, in SIPRI Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security (online: SIPRI, 2011), https://www.sipri.org/yearbook/2011/01. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, ‘Excess Profits Tax on the Arms Industry to Fund International Climate Finance’, Tipping Point North South, 2023, https://transformdefence.org/publication/excessprofitstax/ ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin and Deborah Burton, ‘Global Military Spending, Sustainable Human Safety and Value for Money’. ↩︎

- ‘The “Gaping Gap” in Ireland’s Airspace Defence’, The Irish Times, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/the-gaping-gap-in-irelands-airspace-defence-1.4597124. ↩︎

- Ho-Chih Lin, ‘The Military Industrial Complex: How I Learnt to Stop Worrying and Love the F-35 Lightning Jet’, Tipping Point North South, 2016, https://transformdefence.org/publication/the-military-industrial-complex-how-i-learnt-to-stop-worrying-and-love-the-f-35-lightning- jet/ ↩︎

- Dan Grazier, ‘F-35: The Part-Time Fighter Jet’, POGO, https://www.pogo.org/analysis/f-35-the-parttime-fighter-jet. ↩︎

- Mikhail Gorbachev, ‘Mikhail Gorbachev: When the Pandemic Is Over, the World Must Come Together’, TIME, 15 April 2020, https://time.com/5820669/mikhail-gorbachev-coronavirus-human-security/. ↩︎