by Pauline Conroy

Pauline Conroy is currently a member of a Prison Visiting Committee and a graduate of social science from UCD and the London School of Economics. She has worked across Europe with the European Commission’s programmes against poverty and has been a member of the Mental Health Review Tribunals in Ireland.

Introduction

One of the things that always surprised me…was that this Dáil had a series of Ministers who were what you might call distinguished jail birds in their time – men who for very good reason had spent a long time in jail and very honourably in jail but few of them… showed the House how stupid and futile and degrading is the whole principle of locking up people and how utterly sterile it is and unproductive of any change. It is quite valueless from the point of view of the individual and from the point of view of society.[1]

Noel Browne TD (Houses of the Oireachtas, 1970)

Prison reform, particularly the creation of opportunities for people in prison to rehabilitate and reintegrate, has been slow to emerge from the Department of Justice. This delay from the 1960s to present day has been in spite of the strong efforts of individual senior civil servants. It is certainly not for lack of discussion and debate. The 1980s was a period of considerable research and reporting on prisons by prisoner and social justice-oriented bodies,[2] emphasising rehabilitation amongst other themes. Academics have described this period of increasing concern with rehabilitation as the goal of imprisonment as one of “penal welfarism.”[3] The reports, while attracting mild approval among a small elite of decision-makers in the civil service and main political parties, generated no considerable change decades later.

In this essay, I will consider the role of rehabilitation within the Irish prison system. Firstly, I will briefly trace the development of rehabilitation, both in discourse and practice, within Ireland with a specific focus on parole. Then I will discuss the challenges to rehabilitation within our prisons, the risks for former prisoners upon release, and barriers to integration. Finally, I will reflect upon these risks and barriers in the context of forgiveness for the prisoner.

Development of Rehabilitation

Modern prison systems claim to offer opportunities and rehabilitation to prisoners. The Irish Prison Service declares that part of its mission is “providing safe and secure custody, dignity of care and rehabilitation to prisoners for safer communities.” [4] But what is meant by rehabilitation of prisoners, and how can a system provide for it? These are both conceptual and practical problems. The idea of rehabilitation only entered the vocabulary of the Irish prison system in 1962 when an Inter-Departmental Committee on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders was established. Until then, deterrence and incapacitation of prisoners were the prevailing values of prisons. The Committee’s results were never published. Speaking of the outcome, the Minister of Justice Charles Haughey TD stated that they had “in the main as their aim the social rehabilitation of the offender.”[5]

While Haughey attempted a few reforms in the area of parole and psychiatric care, his successor Patrick Cooney TD did not believe in rehabilitation at all. Three decades later, the Jesuit Centre for Faith and Justice concluded that certain sections of the media “sees justice in terms of imprisonment with a vengeance and ignores the rehabilitative element that is part of the stated aim of penal sanctions.”[6] Have things changed? In 2022, the Minister of Justice Helen McEntee TD announced a plan to change the duration of a sentence after which a prisoner could apply for parole from 12 years to 20 years, or even 30 or 40 years.[7]

Successful rehabilitation demands a level of acknowledgement of wrongdoing by a prisoner where s/he has been convicted of an offence which has led to a custodial sentence and that the principal way to avoid a future incarceration is to desist from committing future offences. This is rehabilitation at the most basic level. Elements of this idea are implicit in Ireland’s two open prisons and those prison regimes where prisoners have the opportunity to mix in the local area, to take up jobs outside the prison or attend further education, returning to the prison in the evenings. Rehabilitation cannot be “delivered” to prisoners. It is neither a gift nor a service.

In terms of specific effects, much may be attributed to the particular conditions of detention, whether they are harsh or humane. This is a view with which the Irish Penal Reform Trust agrees in their critical discussion of reintegration of prisoners after release.[8] Warren Graham, a prisoner speaking from Loughan House open prison, to a Joint Oireachtas Committee on Rehabilitation in 2022 said:

Studying criminology and sociology at third level has enabled me to see my life from the experts’ position and using their opinions and theories I have seen that prison is often considered as containment for the purpose of retribution, not rehabilitation. I see this in Irish prisons. I see that some people are considered no-hope, beyond reach and are merely in prison to serve out their time. They are released and return again continuing the same vicious cycle for the duration of their life.[9]

The European Court of Human Rights in interpreting the European Convention on Human Rights does not guarantee, as such, a right to rehabilitation. The Court’s case-law presupposes that convicted persons, including prisoners with life sentences, should be allowed to rehabilitate themselves. Even though States are not responsible for achieving the rehabilitation of life prisoners, they nevertheless have a duty to make it possible for such prisoners to rehabilitate themselves. In this interpretation, prisoners cannot be the objects of rehabilitation – they are the subjects who make decisions for themselves to change their outlook on life and on their own lives. In this sense, a prison system cannot offer rehabilitation but it can offer opportunities for prisoners to rehabilitate themselves.

In 2016, the European Court of Human Rights discussed rehabilitation in a judgement of some length in the unusual case of a life-sentenced prisoner, Mr James Murray, who had been imprisoned in the Caribbean Netherlands[10] for murder, but who had died before his case was heard. His siblings pursued the case on his behalf. The following are extracts from that judgement:

[T]he obligation to offer a possibility of rehabilitation is to be seen as an obligation of means, not one of result. However, it entails a positive obligation to secure prison regimes to life prisoners which are compatible with the aim of rehabilitation and enable such prisoners to make progress towards their rehabilitation. In this context the Court has previously held that such an obligation exists in situations where it is the prison regime or the conditions of detention which obstruct rehabilitation.[11]

In Ireland, the Parole Act 2019 extended the custodial period of life sentenced and long sentence prisoners from eight to 12 years before they can apply for parole or a sentence review.[12] The current average amount of time served by a prisoner prior to obtaining parole is 20 years. This reinforces the custodial, as opposed to the rehabilitative policy of prisons. The Act provided an opportunity to define rehabilitation, which is at the heart of its significance as a policy change. Section 24 of the Parole Act 2019 proposes that prisons should have the objective of ensuring that there is an incentive for persons serving sentences of imprisonment to be rehabilitated.

A decision on parole for an applicant is to take into account that the parole applicant “has been rehabilitated and would, upon being released, be capable of reintegrating into society.”[13] However, the 2019 Act does not contain a definition of rehabilitation, or how it is to be measured, so both parole applicants and Parole Board members may be in the dark as to the basis on which decisions are to be made in terms of rehabilitation, despite the several other factors on which their decision is made being based in law. The Act creates legal uncertainty about rehabilitation by omitting to define it. What is clear is that the Act distinguishes between rehabilitation – whatever that may be – and reintegration into society. Non-nationals who have been convicted of a crime and will be subject to deportation orders are apparently not eligible for parole. The right to parole therefore is not universal. This is curious since Ireland adopted an EU Directive permitting cooperation in probation and serving of sentences of prisoners but perhaps only applies this to EU nationals.

Social and economic integration is a distinct approach from rehabilitation. The European Union Peace and Reconciliation Programme for Northern Ireland and the Border Counties promoted the concept of reintegration into society for ex-prisoners, sometimes referred to as former combatants, between 1989 and 2020.[14] Reintegration measures for politically motivated ex-prisoners, eligible for release, were based on the principle of self-help with autonomous, ex-prisoner-controlled organisations delivering services to themselves. This was a form of peer-to-peer provision in which some ex-prisoners took responsibility for other ex-prisoners. The question of rehabilitation did not arise. Prisoners were not expected to express remorse. This had been agreed at the level of negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement. The European Union Peace and Reconciliation Fund provided funding to support prisoner re-integration schemes distributed by the Northern Ireland Voluntary Trust – which assisted in financing a “self-help model for reintegration” managed by former prisoners e.g., the Republican organisation Coiste na n-Iarchimi. EU funds were expended on ex-prisoner integration projects in Louth, Cavan, Monaghan, Leitrim, Sligo and Donegal. What the Peace Programme experience demonstrated is that it is possible to have publicly funded self-managed reintegration programmes without insisting on rehabilitative content.

Challenges Within Prison

To promote engagement with prison services and reward good behaviour, the Prison Service has operated an incentivised regime programme for the last 12 years, which adds or subtracts privileges according to a prisoner’s level of regime: basic level, standard or enhanced. The advantages of moving up the levels are considerable, with the prospect of more spending power in the tuckshop and better visiting arrangements. Protection prisoners cannot get an enhanced regime as they do not engage with many services. Prisoners on an enhanced level for some time can apply to go to an open prison. For the system to work there must be sufficient services and activities for prisoners to engage in. Some prisons have excellent workshops, some have not. Some can offer drug treatment, others cannot. This calls into question the universal validity of the incentivised regime as a general road to opportunities for rehabilitation.

The Integrated Sentence Management System (ISM) is widely reported by the Prison Service as a mechanism to facilitate prisoner sentence planning.[15] It applies to prisoners serving sentences of 12 months and more. The idea of individualised sentence planning by and with prisoners is a good idea, supported by the European Prison Rules.[16] Implementing it has been a mixed experience relying sometimes on paper-based reporting, while a prisoner has no copy of her/his plan. If the ISM were to function effectively it would involve a very large number of prison officers interviewing and following up individual prisoners along with new arrivals and imminent departing prisoners. One of the ways around this would be to have officers on prison landings playing a greater part in the process.

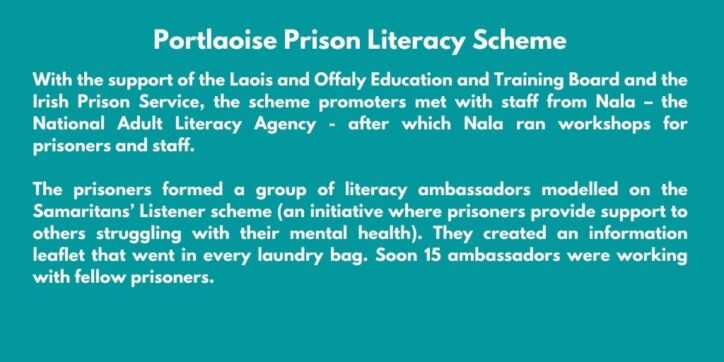

Opportunities for second chance education is a serious contribution to prisoners’ outlook on life. A prisoner is five times more likely to have had only basic or primary school education compared to the population as a whole, with almost 70% of people in prisons leaving school before the age of 14.[17] Education can open up another view of the world, facilitate the acquisition of new qualifications and support family life with school-going children. Education can reinforce personal identity and esteem often damaged by early experiences of school (see Figure 1 below).

A significant minority of prisoners enter and exit prison without any apparent relationship to the State other than as a prisoner in custody. They have no PPS number, have never claimed social welfare, have no driving license, no PAYE Revenue number, have never applied for housing assistance or enrolled in Further Education. This unusual state of affairs was revealed in a Central Statistics Office (CSO) study and follow-up of the almost 3,800 prisoners in custody on the night of Census 2016.[18] Twenty-five per cent of prisoners – almost 1,000 women and men were not just marginal to the State, they functioned outside the State altogether. In this regard these outsider prisoners were state-less or akin to displaced persons.

Offending behaviour, and stepping out of it, is so complex that often the most effective intervention is this communication that takes place between one who is a couple of steps further on than the other and who knows how to navigate his thoughts and feelings and provide information on what one must do to stop offending.[19]

Mark Johnson (User Voice, 2013)

The CSO study found that more than half of all prisoners did not continue education beyond primary school. Levels of education were substantially lower than for the population of Ireland. Only 12 per cent had what the CSO describes as “substantial employment” – that is, they earned at least €100 per week. Of those 1,720 prisoners not in education or substantial employment in 2019 on leaving prison, 12 per cent were in insubstantial employment. Examples of employment include selling race cards on race days, selling rosettes outside football matches, casual labouring, and events, temporary agency cleaning, car park attendant.

This poses the question of what rehabilitation means to those prisoners who arrived in prison already unintegrated into civil society, from disadvantaged areas, operating outside the formal labour market and with minimal levels of education. They have no civil society identity.

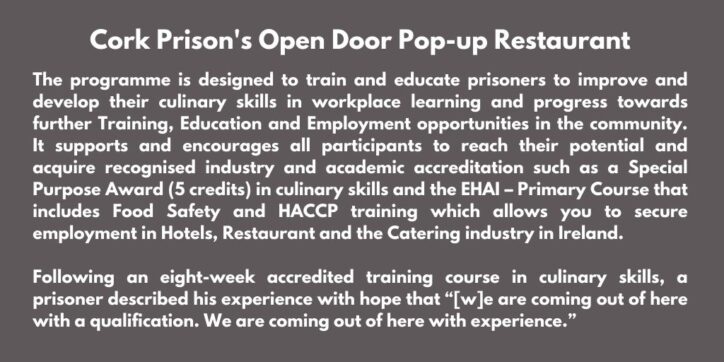

In theory, opportunities for rehabilitation should begin at the start of a prison sentence. This is not always the case. There can be long queues for psychological therapy, an absence of occupational therapy, insufficient workshops with accredited vocational training—though some examples exist, see Figure 2 above— and some prisons have no provision for drug detoxification and treatment.

Risks on Release

Release from prison has its own risks. International Probation expert Charlie Brooker has devoted extensive research resources to examining how probation works in the UK and other comparable countries from the perspective of the prisoner and the probation service. Speaking in Dublin in 2021, he presented data which showed very high death rates among UK prisoners on probation compared with the death rates of prisoners in custody, as did a significant report from the UK Howard League for Penal Reform.[20]

In the case of Ireland, an alternative measure of release risk can be calculated using the reports on deaths in custody and on temporary release investigated by the Inspector of Prisons.[21] This has the advantage of including those who are not on probation and not serving long sentences. There were 50 deaths in custody investigated between 2016 and 2020 of which 25 were on temporary release. Of the 25 prisoners who died on temporary release, there was no information on the circumstances of two, 15 died of illnesses. The remaining eight died in other circumstances such as found dead, died in fire, shot dead, suspected drug overdose, died shortly after suicide attempt, found dead at home or elsewhere, and single vehicle collision. This measure reveals that almost one in three prisoners on temporary release for reasons other than illness do not survive release.

In the words of a former prisoner, “It’s like there’s a tin of biscuits and we’re all the broken biscuits at the bottom of it.”

Of those who do survive release, a crude measure of rehabilitation is recidivism – the rate at which men and women released from a prison sentence are reconvicted within a period of time. This rate is high in Ireland. For those released from prison in 2018, almost 48 per cent had reoffended within a year. For those under 21 years of age, 70 per cent had reoffended a year after release. On the face of it, these figures suggest that a sentence of imprisonment is not effective in rehabilitation in terms of prisoners sustaining a crime-free life.

Before leaving prison, every prisoner should have a wallet or purse containing their immediate address, their social welfare office, and a copy of their application for benefits. If not on probation they should have a named key worker where they can get advice. Where appropriate they should have already been registered with a methadone clinic.

Barriers to Integration

For example, some prisoners on release may not have family support. While the prison sentence is the punishment, for many prisoners, punishment begins or continues upon release.

Paddy Richardson (IASIO, 2014)

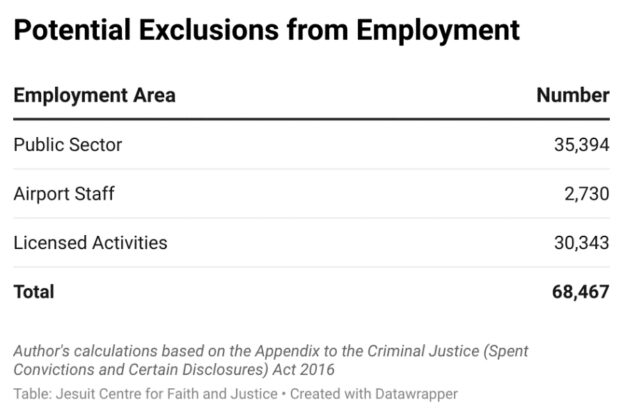

A barrier to prisoner reintegration is a practice ostensibly designed to protect the general public from the risk of prisoner release, namely Garda vetting. Employment candidates must disclose convictions prior to or in employment in specific jobs.[22] Certain other jobs or economic activities which are “licensed” carry compulsory Garda vetting prior to obtaining or not obtaining a licence for holding a security industry post or taxi licence. The number of potential exclusions are considerable (see Table 1 below).

The Garda Vetting system and obligatory disclosure of convictions has been designed to protect the public, and are in many instances necessary, but for the prisoner it can seem like a second punishment where s/he is denied the second chance after serving her/his time. The life sentence prisoner released on license has no sense of an ending. His/her sentence ends at death.

Secondly, voluntary activity is affected through a legal prohibition on a former convicted prisoner becoming a charity trustee. The ban can only be appealed to the High Court. Former convicted or sentenced prisoners are disqualified from any decision-making role in a Charity, including voluntary bodies working with ex-prisoners. Section 55 disqualifies a person who is, either, convicted on indictment of an offence, or is sentenced to a term of imprisonment by a court of competent jurisdiction.

The third barrier arises in education. Higher Education Universities and Institutes of Technology can require student applicants to be Garda vetted and may refuse a place on a course to an aspiring student who has been convicted of a crime. It is comprehensible that jobs with children, minors and vulnerable persons should be protected employment. However, the reach is much greater than these employments. The University of Limerick, as an example, requires Garda Vetting for admission to 21 courses including: BA in Performing Arts, BSc in Sport and Exercise Sciences, BSc in Physical Education, B. Ed Languages. The Teaching Council has wide ranging powers in the registration and re-registration of teachers, including vetting and in disclosures.

Education has been and still proves to be a proven method of reducing criminal behaviour. It allows individuals become productive members of society, break away from a cycle of poverty and imprisonment and improves their life opportunities. This legislation has the potential to lead to safer communities, parents engaged in their children’s lives and not in prison.

Niall Walsh (Pathways Project Dublin, 2019)

On the one hand, prisoners are supposed to prepare for integration into employment, education or voluntary work but, on the other hand, the pathways are strewn with dozens of barely visible and unexpected barriers.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have highlighted the presence of “rehabilitation” within penal policy discourse and practice for over sixty years. Yet many challenges, risks and barriers remain for those within our prisons and those re-entering society. Rehabilitation is an individual determination to change an outlook on the world. It is encouraged by actions, measures, environmental alterations, services, and programmes providing opportunities. Rehabilitation is a transformative process by an individual who rehabilitates him or herself. It cannot be imposed, donated, or promised by others. It is a means not an outcome.

There are many reasons why prisoners might not be able or do not have the opportunity to avail of rehabilitation opportunities. The barriers to rehabilitation and reintegration opportunities remain high for those released from prison; both as potential students and employees. Rehabilitation opportunities can be provided on both sides of the wall: in prison and outside in neighbourhoods and townlands. The many and unexpected barriers suggest that prisoners are not forgiven for their convictions when out of prison. Their punishment continues in a different form of separation and exclusion once their sentence has ended.