Introduction

‘There is nothing so practical as a good theory’, the famous maxim of Kurt Lewin, has particular relevance for the reform of our public services. In that challenging task, there is need for a coherent theoretical perspective and clarity as to the fundamental goals we as a society wish to strive for in the coming decades. I want to argue for a radical new paradigm for public services and to describe such a paradigm. I will discuss the implications of this paradigm using the case example of health services and will seek to draw some broad applications for the community and voluntary sector in relation to the design and delivery of public services.

I believe that the OECD Public Management Review, Ireland: Towards an Integrated Public Service, completed in 2008, has a failed paradigm at the heart of the thinking it presents. The very opening sentence of the report is illustrative of this:

Ireland’s economic success story is one that many OECD countries would like to emulate. While the reasons underpinning Ireland’s success are varied, the Irish Public Service has played a central role in ensuring that the right economic, regulatory, educational and social conditions are in place to facilitate growth and development.1

Even without the benefit of hindsight, this would have to give rise to serious questioning.

The Need for Change

There are compelling reasons for reforming Irish public services. These include the many failures and defects documented in reports relating to these services, the unsustainable costs of providing services through the present delivery systems, and the mounting case that our public services are not ‘fit for purpose’, especially given the challenges facing a changing and crisis-laden society.

Confronted by the need for radical reform, it would be a fundamental error simply to surrender to a ‘neo-liberal’ recipe for withdrawal of services in order to achieve fiscal consolidation. Indeed, we need to recognise that there are powerful forces which see the current crisis as providing the ideal conditions for pursuing an ideology-based assault on the very notion of tax-funded, publicly provided or supported services. And we need to recognise also that there are those who see the ‘solution’ to the problems in our public services as requiring nothing more than adopting the precepts and practices of dominant management approaches in the private sector. This is advocated without regard to either the values and ethos of the public sector or the reality that some of these management approaches have led to catastrophic failures in the private sector. Instead, we need to grasp the opportunity provided by the current deep-seated crisis to explore fundamentally a model for Irish public services appropriate for the twenty-first century. We need to devise a new paradigm which will deliver essential and quality public services at a cost that people in Ireland will be able to support in the future.

A New Paradigm: The Human Development and Capability Approach

Our challenge is to build what might be described as a ‘citizen society’.2 There is an extensive philosophical and practical literature which describes the building blocks of such a society and the approaches essential to putting the citizen3 at the centre of the design and delivery of public services.

In this regard, there are two broad and converging streams of thought which are directly relevant to the challenges now facing Irish society. The first relates to the revival of civic republicanism as a normative political theory, and the second to a human development and capabilities approach. The former is associated with the Irish political philosopher, Philip Pettit, and the latter is associated with Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum.4

Both these vital streams of thought have as their essential focus the creation of what may be described as a ‘flourishing society’.5 The fundamental question we need to ask is: ‘what are citizens actually able to do and to be?’ It follows that the political and social arrangements that we, as a society, put in place, and in particular the design of our public services, should have as their raison d’etre the expansion of people’s capabilities – the freedom and equality of condition to achieve, for every person, valuable ‘beings’ and ‘doings’. This approach radically subverts the dominant paradigm whereby the national measure of progress relates only to GDP or GNP.

Fundamentally, the wisdom underlying this approach is very ancient indeed. Aristotle was adamant that the pursuit of wealth is not an appropriate overall goal for a flourishing society: in his Ethics, he states: ‘clearly wealth is not the good we are seeking, since it is [merely] useful [choiceworthy only] for some other end.’

The human development and capability approach sets out to measure our progress on the basis of human development across a wide range of dimensions and asks whether human capabilities are being developed in each key area of living. Eddie Molloy has advocated a ‘balanced scorecard’ to chart our progress, or lack of it, arguing that we need measures in the following key areas: wealth creation capacity, infrastructure, quality of life and social justice, and in regard to public services institutions that are ethical, competent and accountable.6

The core concepts around which a ‘citizen society’ may be developed include:

The Common Good: the public services of the State should serve the common good, the res publica, not private or vested interests.

Inclusion: the design and delivery of public services must involve and include citizens directly and as a matter of course.

Deliberation: every public service must be shaped by a process of public deliberation where reasoned justification is presented in open discussion as to how decisions and services pertain to the common good.

Independence and ‘non-domination’: public services should create conditions which prevent citizens dominating each other in social and economic life and seek to develop the human agency of each citizen on the basis of the equal regard and dignity of every person.

Participation: public services must facilitate citizens in developing their capabilities so that progressively we are able and willing to participate in collective decision-making in a public-spirited fashion.

Equality: public services must be based around the goal of creating ‘equality of conditions’ so that we achieve a fundamental equality of income and wealth in order to ensure the equality of citizenship essential to a republican and flourishing society.

These are extremely challenging concepts. In our political culture they are not well understood, and where they are articulated with effect they meet fierce ideological resistance. However, in a situation where the prevailing ideology has been shown to result in disastrous consequences, there are now opportunities for reconstruction of our failed political entities. We need to conceive of a new model of citizenship as the basis for a transformed state. We need to understand the potential for citizenship development which may reside in the design and delivery of public services: civic engagement must be at the heart of developing political communities at local level and at national level.

Our public services to date have been underdeveloped from a civic perspective because of passive models of delivery and narrow understandings of solidarity; indeed, they have evolved from a ‘Poor Law’ mentality and with impoverished concepts of human development. The task of collective government is to empower and enable all citizens to pursue a dignified and at least a minimally flourishing life: to achieve this we need participative public services that enrich citizenship as each person has a real opportunity to contribute to policy development, and to the design and provision of services.

Outcomes of services such as those in the health, education, security, environment, and other policy arenas, are ‘co-produced’ by users and providers; hence it makes sense to ensure public participation to facilitate successful outcomes. This simple truth is ignored by centralisers, bureaucrats, ‘power-hoarders’ and vested interests across every public service in Ireland: no wonder, then, that our outcomes are so appalling for the money invested.

Essence of Capability Approach

Before looking briefly at the implications of the human development and capability approach for public service reform in relation to one key set of public services – those concerning health – it may be helpful to say a little more as to what such an approach involves. Instead of conceiving of human beings as simply self-interested, as in the neo-liberal paradigm, the human development approach recognises that human beings are social beings with altruistic concerns and that they aspire to have regard for others. In this approach, people are seen to be active, creative and able to act on behalf of their aspirations – there is a fundamental concern for human agency and this means that participation, public debate, democratic practice and empowerment are to be fostered as essential to our human well-being.

If our state apparatus perceives people as dependants, supplicants, clients or ‘patients’, the result will be the phenomenon which might be described as ‘capability deprivation’. The realisation of this is not new: the words which John Stuart Mill wrote in the concluding section of his classic work, On Liberty, published in 1859, ought to be to the forefront of our approach when reforming our public services:

The worth of a State, in the long run, is the worth of the individuals composing it; and a State which postpones the interest of their mental expansion and elevation, to a little more of administrative skill, or that semblance of it which practice gives, in the details of business; a State which dwarfs its [people], in order that they may be more docile instruments in its hands even for beneficial purposes – will find that with small [people] no great thing can really be accomplished; and that the perfection of machinery to which it has sacrificed everything, will in the end avail it nothing, for want of the vital power which, in order that the machine might work more smoothly, it has preferred to banish.7

The words of Wilhelm Von Humboldt, used by Mill for his ‘Dedication’ in On Liberty, might be another guiding light in the debate on reforming public services:

The grand, leading principle, towards which every argument unfolded in these pages directly converges, is the absolute and essential importance of human development in its richest diversity.

So, in designing public services we need to ask how they are assisting the essential human functionings and capabilities – the valuable activities and states that make up people’s well-being. Martha Nussbaum’s proposal that we seek to secure for all citizens at least a threshold level of her ten ‘central capabilities’ provides one very thoughtful framework for a total reform of how we design and provide services. The ten central capabilities are spelled out under the headings: life; bodily health; bodily integrity; senses, imagination, thought; emotions; practical reason; affiliation; other species; play; control over one’s environment.

To ask how we are expanding human capabilities is an even more important question than asking what the State should provide in the way of public services.8 Sen’s important question is: ‘what substantive freedoms does one enjoy to lead the kind of life one has reason to value?’9 The key idea in the capability approach is that social arrangements should aim to expand people’s capabilities – their freedom to promote or achieve valuable ‘beings’ and ‘doings’.

This is a radically different paradigm to the one which has predominated to date and which is governed by goals of maximising income or commodities or utility. We now know that if policies aim only to increase these goals they distort and diminish people and the lives they have the potential to lead. Much conventional economic thinking is based upon a utilitarian approach – how best to have most ‘desire-fulfilment’, as measured by commodities or money. What the human development economists, such as Sen, are saying is that the basic objective ought to be to create an enabling environment for all people to enjoy long, healthy and creative lives. This may appear to be a simple truth but it has been quite ignored in the dominant concern for the accumulation of commodities and the growth of income. This may have resulted in rises in average incomes and wider access to consumer goods, but we are now increasingly aware that it has in the process led to staggering levels of inequality in incomes and wealth and a concentration of power in the hands of the elites in our society.

The Human Development Index, developed by the UN, is a better index of well-being and capability than GDP per capita because it includes income but also literacy and schooling and life expectancy as indicators of well-being. In Ireland, we have as yet inadequate levels of data in relation to many of the indicators we will need to measure if we are to adopt more a comprehensive measurement of development. However, much progress in relation to data collection and dissemination has been made by the Central Statistics Office and others in recent years and this will need to be built on if we are to begin to develop and use a ‘balanced scorecard’ of our progress.

Health Capability

Let us look at one area of our public services to explore how the capability approach might lead to a vast change in effectiveness and efficiency: our troubled health services.

Scale of Morbidity

First, consider some statistics from the most recent HSE Annual Report about the levels of morbidity in our society of just 4.58 million people. In 2010, 1.1 million people attended the 33 emergency departments of our public hospitals; of these, 30 per cent required admission to inpatient care. There were 3.5 million attendances in outpatients departments (of which one million were new attendances); 588,860 people received inpatient hospital care (involving the use of 3.6 million ‘bed days’); over 730,000 day case treatments were provided.10

These figures relate only to the levels of morbidity cared for in the public hospital sector and do not take account of illnesses cared for in the primary and community care sector where, in 2010, we spent €7.7 billion as against €5.2 billion in the hospital sector. The Irish College of General Practitioners estimates that each year in Ireland there are 16 million GP consultations with patients.11

Are we a sick society and getting sicker? People are living longer but why are so many living with chronic diseases? Such diseases are now at epidemic levels; treating them accounts for between 70 and 80 per cent of health care expenditure. The Chief Medical Officer has written:

Our ageing population, together with adverse trends in obesity, diet, exercise and other risk factors means that the level of chronic health conditions will certainly increase. There is much which can be done because approximately two thirds of the predicted disease burden is caused by risk factors which can be prevented …

In parallel with the ageing of the population there will be a very significant increase in the prevalence of chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, mental illness, dementia and locomotor disabilities.12

Resources and Health

It is clear that conventional approaches to health care are simply not adequate to cope with the challenges presented by the key public health issues now facing our society (including obesity levels, harmful patterns of alcohol consumption and socio-economic differentials in health status) and that these current approaches are becoming unsustainable.13 By looking at health from the perspective of the human development and capability approach, a sustainable public health service may be conceived and overall population health may also improve. What we need to reflect on very seriously is that the resources devoted to health systems are not the determining factor in achieving optimum health outcomes: what is key is how societal resources are used and distributed.

The USA is the classic warning case in this regard: there, over 16 per cent of national wealth is devoted to the health system for very poor returns in terms of either the outcome for large numbers of people who need to use health services, or overall population health. Economic growth only contributes to human flourishing (in terms of improved health) when it is followed by a shift in resource-allocation towards effective health interventions and by equitable distribution of income and employment opportunities.

Angus Deaton has highlighted how many contributions to health do not depend on economic growth or income – there are examples of countries where health gains have been achieved without high incomes.14 As Sen and others point out, we can improve health without high economic growth but that depends upon adopting a radical new paradigm for health improvement. One of the distinguishing features of the human development and capability approach is its focus on the process of generating health. Sen writes:

The factors that can contribute to health achievements and failures go well beyond health care, and include many influences of very different kinds, varying from (genetic) propensities, individual incomes, food habits and lifestyles, on the one hand, to the epidemiological environment and work conditions on the other… We have to go well beyond the delivery and distribution of health care to get an adequate understanding of health achievement and capability.15

‘Good Health Policy’ or ‘Good Policy for Health’?

Health policy and public services in health cannot be isolated from the overall set of public policies pertaining to the distribution of the ‘social determinants of health’. For example, health policy is not only about providing treatment for people with diabetes but about dealing with the social and economic drivers of the obesity epidemic. In relation to designing and delivering public services across all public service areas, what we need is to enable people to develop, to the maximum extent possible:

- the ability to be well nourished;

- the ability to be free from illness;

- the ability to live long lives.

The Department of Health: Willing to envisage

‘shared health governance’? © D. Speirs

Jennifer Prah Ruger’s book, Health and Social Justice, is a seminal work on the application of the capability approach to health and the promotion of social justice. Her argument is that justice demands that society should as far as possible ensure that individuals are capable of avoiding premature death and escapable morbidity to a threshold that is their unique maximum; that they are enabled to do this through appropriate and necessary medical care, public health interventions and health research; and that the implementation of these measures involves the active participation of all the relevant actors while using the least amount of resources. Health capabilities are the focal variable for assessing equality and efficiency in health policy. As Sen states, we need to distinguish between ‘good health policy’ and ‘good policy for health’: ‘The pursuit of health justice has to go well beyond getting the institutions of health care right, since people’s health depends on a variety of societal influences, of which health care is only one.’16 Ruger’s ‘health capability paradigm’ seeks to map out steps by which we get to the point where citizens – through their health functioning and health agency – voluntarily embrace changes in our economic and social structures, and in their own behaviour, to achieve a shared vision of the ‘flourishing society’. We need to articulate new public norms supporting our best aspirations. Here there is a vital role for the community and voluntary sector: grass-roots initiatives, strong leadership and public education are all part of the required norm-building process. The community and voluntary sector in Ireland is very extensive: it employs 36 per cent of the country’s healthcare staff and has the capacity to lead the debate towards the new paradigm.17

The ‘health capability paradigm’ envisions shared health governance in which citizens, providers, and public institutions work together to create a social system and environment enabling all to have the opportunity to be healthy. This will mean consensus-building around substantive principles and distribution procedures, accurate measures of effectiveness, changes in attitudes and norms, and open deliberation to resolve problems. Ensuring health capabilities requires promoting health agency and equipping individuals and communities with the tools they need to pursue and achieve health outcomes they value and have reason to value. We need to develop a people-based health culture which will equip our citizens to participate in designing public services, to deliver changes in their behaviour, to take responsibility for health outcomes and for the health status of their own areas and communities. We must re-imagine ‘an enabling State’ in place of the ‘controlling and dependency-creating State’ which now exists.

It is relevant to the current Irish health policy arena that Jennifer Prah Ruger maintains that the ‘health capability paradigm’ rests on medical necessity and appropriateness, not on the ability to pay. Writing in an American context, she argues that progressively financed universal health insurance is fundamental and essential for human flourishing: she argues that it reduces vulnerabilities and insecurity throughout our lives and this protective security supports ‘both overall health and capabilities beyond health – the capability to work, to manage a household and family, to engage in civic affairs, to live a flourishing life’.18

In sum, as a people we must seek good health and the ability to pursue it: our conventional approach to the provision of health services sees people as consumers or patients rather than as citizens and health agents. The ‘health capability paradigm’ integrates health outcomes and health agency – health agency being defined as the ability of people to achieve the health goals they value and to act as agents of their own health. Attributes such as self-management, decision-making ability, skills, knowledge and competence, and the exercise of personal responsibility are crucial to the citizen’s participation in all public services but especially with regard to their own and other people’s health status and health outcomes.

The notion of social obligation is central to the new paradigm: we have a fundamental societal obligation to ensure the conditions for all to be able to be healthy. This is underpinned by universal health insurance. We must enable and empower citizens to shape and design and help govern not only our health system but also the wider provision of public services; as already noted, the broader environment is as relevant to raising the health status of people as are the health services.19

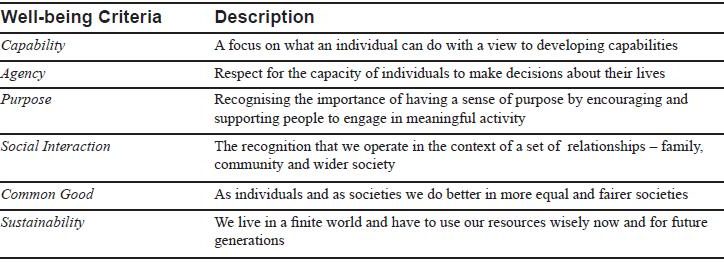

The National Economic and Social Council (NESC) report, Well-being Matters: A Social Report, published in October 2009, is the first major report to relate the human development and capability approach to public policy-making in Ireland. Placing policy-making in the context of a ‘developmental welfare state’ model, the report proposes a ‘Well-being Test’ (as outlined below)which ought to be applied in reforming our public services.20

The Role of the Community and Voluntary Sector in Public Services

A range of approaches or models is apparent in regard to the relationships which may exist between the voluntary sector and the State in the provision of public services:

The philanthropic approach – essentially, the State is content for charitable bodies to fund and provide services which it cannot currently fund – or does not want to;

The protest approach – voluntary bodies and social movements seek to advocate for changes in services;

The self-help approach – whereby citizens seek to provide some service by themselves without interaction with the State;

The co-production approach – where the voluntary sector and the State have an effective partnership in the design and provision of services.

The ‘co-production approach’ is similar to the ‘active partnership’ model which I outlined in a book published over ten years ago, Citizenship and Public Service.21 In it, I set out the philosophical basis for active citizenship in a pluralist democracy which legitimates voluntary action in our society. That key argument of that book I would make in even stronger terms in 2011. The co-production or ‘active partnership’ models stand in sharp contrast to the ‘dependent partnership’ model which still remains the experience of the vast majority of voluntary providers of public services through service agreements with State agencies.

Finally, the essence of the task of promoting the active involvement of citizens in the design and delivery of public services, including health care, is well captured in the ‘C.L.E.A.R. Framework of Factors Driving Public Participation’:

- People participate when they can – when they have the resources necessary to organise, mobilise and make their argument.

- People like to participate when they think they are part of something – because the arena is central to their sense of identity and their lifestyle.

- People participate when they are enabled – by an infrastructure of good civic organisations that channel and facilitate participation.

- People participate when they are asked for their opinion.

- People participate if they are listened to, not necessarily agreed with, but able to see a response.22

Well-Being Test

Notes

1. OECD, Public Management Reviews – Ireland: Towards an Integrated Public Service, Paris: OECD, 2008, p. 11.

2. I take the phrase from Stuart White and Daniel Leighton (eds.), Building a Citizen Society: The Emerging Politics of Republican Democracy, London: Lawrence and Wishart, 2008.

3. The word ‘citizen’ is used here not in an exclusive sense – referring only to those who live in Ireland and hold citizenship of this country – but rather in the broader sense of including those who are living here and are part of society.

4. See Philip Pettit, Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997, and Martha C. Nussbaum, Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

5. TASC – the progressive think-tank – has underway a project to articulate a vision for a flourishing society in Ireland and to produce a series of papers addressing aspects of this vision (see www.tascnet.ie).

6. See Eddie Molloy, ‘Ireland’s Sixth Crisis – Severe Implementation Deficit Disorder’, Paper to the 30th MacGill Summer School on ‘Reforming the Republic’, 19 July 2010; see also National Economic and Social Council, Well-Being Matters: A Social Report for Ireland (two volumes), Dublin: NESC, 2009 (Report No. 119), for an excellent overview. In a paper to the 2011 MacGill Summer School, Eddie Molloy drew attention to the fundamental importance of values, at both individual and institutional level, in bringing about political, economic and public sector reform (Eddie Molloy, ‘Public Service Reform: The Central Role of Character and Culture’, Paper to the 31st MacGill Summer School, 26 July 2011).

7. See John Stuart Mill, On Liberty (edited and with an introduction by Gertrude Himmelfarb), London: Penguin Books, 1974, p. 187.

8. See Nussbaum, op. cit., pp. 33–34.

9. The work of Nobel prize winning author, Amartya Sen, crosses many disciplines but his corpus may be best approached in the following: Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom, Oxford: Oxford University Press,1999 and The Idea of Justice, London: Penquin Books, 2009, and in Christopher W. Morris (ed.), Amartya Sen, Contemporary Philosophy in Focus Series, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

10. Health Service Executive, Annual Report and Financial Statements 2010, Dublin: HSE, 2011, pp. 40–41.

(www.hse.ie)

11. Irish College of General Practitioners, Submission to Joint Committee on Health and Children, January 2009, p. 2.

12. See Chief Medical Officer, ‘On the State of Public Health’, Brief for Minister for Health and Children, March 2011.

(http://www.dohc.ie/publications/briefings_foi_2011.html)

13. See Fergus O’Ferrall, ‘The Reform Challenges in Irish Healthcare’, Studies, An Irish Quarterly Review, Vol. 100, No. 398, Summer 2011, pp. 155–166. I have set out the argument for increasing citizen participation in more detail in Fergus O’Ferrall, ‘The Erosion of Citizenship in the Irish Republic: The Case of Healthcare Reform’, The Irish Review, Vol. 40, Nos. 40–41, Winter 2009, pp. 155–170; see also Fergus O’Ferrall, ‘Citizen Participation in Healthcare’, in Eilish McAuliffe and Kenneth McKenzie (eds.), The Politics of Healthcare: Achieving Real Reform, Dublin: The Liffey Press, pp. 179–206. On health inequalities see Sara Burke and Sinéad Pentony, Eliminating Health Inequalities: A Matter of Life and Death, Dublin: TASC, 2011.

14. See Angus Deaton, Global Patterns of Income and Health: Facts, Interpretations, and Policies, Cambridge, MA: The National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006 (Working Paper 12735).

15. See Amartya K. Sen, ‘Why Health Equity?’, Health Economics, Vol. 11, Issue 8, December 2002, pp. 659–666 (at p. 660).

16. Foreword by Amartya Sen in Jennifer Prah Ruger, Health and Social Justice, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, p. ix.

17. The Health Spoke, The Wheel, Scoping the Community and Voluntary Healthcare Sector in Ireland: A Literature Review, Dublin, 2005.

18. Jennifer Prah Ruger, op. cit. pp. xv–xvi.

19. See Jennifer Prah Ruger, ‘Health Capability: Conceptualization and Operationalization’, American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 100, No. 1, January 2010, pp. 41–49; see especially, Box 1, ‘Health Capability Profile’, which sets out select concepts and domains for a health capability classification and the components of a working health capability profile, and Figure 1, ‘Conceptual Model of Health Capability’.

20. National Economic and Social Council, op. cit., p. 156.

21. Fergus O’Ferrall, Citizenship and Public Services: Voluntary and Statutory Relationships in Irish Healthcare, Dublin: The Adelaide Hospital Society in association with Dundalgan Press, Dundalk, 2000. The contribution of community and voluntary healthcare organisations is the focus in: Fergus O’Ferrall, ‘People Centredness: The Contribution of Community and Voluntary Organisations to Healthcare’, Studies, An Irish Quarterly, Vol. 92, No. 367, Autumn 2003, pp. 266–277.

22. Vivien Lowndes, Lawrence Pratchett and Gerry Stoker, ‘Diagnosing and Remedying the Failings of Official Participation Schemes: The CLEAR Framework’, Social Policy and Society, Vol. 5, Issue 02, 2006, pp. 281–291, cited in National Economic and Social Forum, Improving the Delivery of Quality Public Services, Dublin: NESF, 2006 (Report 34), p. 48.

This is an edited version of a paper presented to a conference, ‘Putting People at the Heart of Public Services’, organised by The Wheel, and held in Dublin Castle on 7 July 2011.

Dr. Fergus O’Ferrall is Adelaide Lecturer in Health Policy, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Trinity College, Dublin.