Introduction

If money were scarce, and one had to prioritise where to invest in rehabilitative facilities within prison, where would you invest it? I suggest that the greatest return is likely to be found amongst the younger prison population who are still at a very decisive developmental period in their lives, namely the 16 -21 age group. Hence for evidence of any sort of political commitment to rehabilitation within prison, one might expect to look at the detention centres and services for young offenders.

Fort Mitchell had a capacity of 102, almost all under 25, the majority of them between 16 and 21. The regime was very much educational focused. Despite offering young people a far more rehabilitative programme than any other prison in the State, it was closed in the dispute about overtime between the Minister and the Prison Officers Association .

Shanganagh Castle, despite being the only open centre for young offenders, and despite the fact that it is widely recognised that imprisoning people in conditions that are unnecessarily secure is harmful to their rehabilitation, was closed, as it occupied a financially valuable site.

That leaves St. Patrick\’s Institution as the only dedicated prison for young offenders. Surely, the closure of Fort Mitchell and Shanganagh Castle were unfortunate, but, for reasons unknown to us lesser mortals, necessary decisions made by a Department of Justice whose commitment to rehabilitation can be found in that only institution for young offenders which remains, namely St. Patrick\’s Insitution?

St. Patrick\’s Institution

St. Patrick\’s Institution caters for about 200 young men, aged 16 to 21, of whom about 60 to 70 are under the age of 18, who are at a most impressionable age, still in adolescent development and full of vitality and energy.

‘St. Patrick’s Institution is a disaster,

an obscenity and it reveals the

moral bankruptcy of the policies of

the Minister for Justice’.

It accommodates the most difficult (and therefore the most damaged) children in our society. Many of them suffered abuse, violence or serious neglect in their earlier childhood, sometimes in other institutions of the State. That abuse was never adequately addressed, sometimes not even acknowledged. The failure to address that abuse is partly – largely – responsible for the subsequent behaviour which has led them to St. Patrick’s Institution. Almost all of them have left school early, without any qualifications. 50% are illiterate. In short, it contains young people who by and large have been victims of family and community dysfunctionality and have already been failed by all the important State services with which they have interacted during childhood and adolescent. What happens or does not happens to them during these years in St. Patrick\’s Institution can have a very significant impact on the rest of their lives.

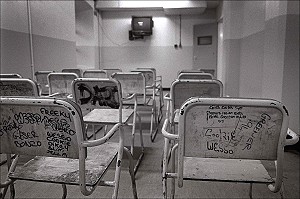

St. Patrick\’s Institution is a disaster, an obscenity and reveals the moral bankruptcy of the policies of the Minister for Justice. In the 1970s and 80s, when this country did not have two pennies to rub together, there were 18 workshops in St. Patrick\’s Institution providing a range of skills to those detained there. Until September 2006, there were none, all closed since 2003 because of funding cutbacks. (In September, following widespread criticism, a small number of workshops were rapidly opened).

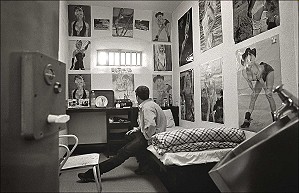

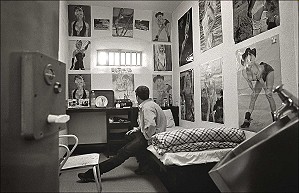

The one-to-one literacy scheme was closed, because of funding cutbacks. In 2004, out of 1300 committals to St. Patrick\’s, 24 sat for one or more subjects in their Junior Certificate. Most young men in St. Patrick\’s spend 19 hours each day alone in their cells and the other five hours mindlessly walking up and down a dreary, depressing yard with nothing to do except to scheme (with enormous ingenuity, it must be said) how to get drugs into the place to kill the boredom. Young people who explode in frustration, are punished by being placed in solitary confinement in the basement, where they are locked in their cells for 24 hours a day, with no contact with other prisoners, no cigarettes, and nothing to do except sleep for three days. Other lesser punishments for infringement of rules include deprivation of visits, letters and phone calls, the very things which help to make time in prison bearable.

Despite the fact that about one-third of the population of St. Patrick\’s are legally children, under the age of 18, there are no staff with child care qualifications, the various agreed standards for children in the care of the State do not apply, there is no inspection by Special Services Inspectorate, there are no care plans for the young people there as required for all children in the care of the State, the young people there do not necessarily have a social worker as required for all children in the care of the State, the required documentation detailing all interventions by staff with the young people in care is not kept and the Children\’s Ombudsman is prohibited from investigating complaints or allegations by the young people accommodated there. Nothwithstanding the fact that there are many fine prison officers who wish to do their best for the young people in St. Patrick\’s, the system dictates that any aggression shown to staff will frequently invite a totally inappropriate violent response towards the young person, which would, in any other residential institution, result in instant dismissal of the staff involved and possible prosecution for assault.

St. Patrick’s Institution is nothing but a “warehouse” for young people, many of whom were broken by their childhood experiences. In this harsh and punitive system, they are further broken down. It is a demoralising, destructive and dehumanising experience, with no redeeming features, characterised by idleness and boredom, for young people, who are full of energy, at a critical time in their development. One young person there summed it up very succinctly when he told me: “This place brings out the worst in you.”

Education and Literacy

Priority of Education within rehabilitation:

The young people in St. Patrick\’s Institution are, almost universally, characterised by educational failure. The educational system has failed them and they consequently have failed to achieve within the educational system. Given the critical importance of education for the future life prospects of a young person, rehabilitation must give priority to making up for the prior failure of the educational system, in order to give these young people some possibility, in future life, of competing on a level playing field. Low educational achievement reduces a young person\’s options in life to such a level that they are likely to no longer share agreed values.

Priority of Literacy within education:

Within the educational system, literacy is of course the most basic issue. In the Literacy Survey of 2003, 80% of the population of St. Patrick\’s scored at or below the second lowest literacy level, with one-third of the prisoners at such a low level that they have to be described as “illiterate”. Illiteracy, or low levels of literacy, not only contributes enormously to low self-esteem but also excludes a person from almost all further education. Rehabilitation then must first enable young people to achieve a competancy in literacy and numeracy, without which further educational achievement becomes impossible.

One would therefore expect that in St. Patrick\’s, a commitment of resources would be provided to enable every prisoner to achieve basic literacy levels. There would also be a commitment of resources to enable each prisoner, within the time-frame available to them, to make up for the failures of the educational system in their childhood. While acknowledging the commitment of the teachers in St. Patrick\’s which enables 50% of the prisoners to participate in at least one educational activity per week, and 25% to avail of at least 10 hours education per week, a serious attempt at rehabilitation would seek to achieve a lot more.

The biggest obstacle to achieving a lot more is the daily regime of St. Patrick\’s. Despite “serving” a client group whose needs are quite different from any other group within the prison system, St. Patrick\’s Institution has not only a physical structure which is identical to that of the adult Mountjoy Prison but much more seriously, has a daily regime that is also identical to that of adult prisoners in Mountjoy. By the time prisoners are actually unlocked and a prison officer collects them for the school, there is less than one and a half hours available for education in the morning and the same in the afternoon.

Apart from a futher hour and a half in the evening, when the school is closed, this is the only recreational time available to them. The desire to freely associate with their friends during these periods, the negative experience of school that they bring with them into prison, the embarassment of being illiterate and the total boredom and mindless meaninglessness of most of their day makes the effort needed to engage in educational activities distinctly unattractive for many.

Locking juveniles up on their own for 19 and a half hours a day, with educational activities having to compete with recreational activities for the other four and a half hours, does not encourage young people to engage in education. A serious attempt at rehabilitation would have made sure that the one-to-one literacy scheme was expanded to include all those who require it – instead it was abolished, because of funding cutbacks.

Training for post-release employment

Most of those committed to St. Patrick\’s Institution were unemployed at the time of committal, many had been unemployed for all or most of their lives. Helping such young people to obtain the personal and interpersonal skills which would help them to secure employment, which they could access on release, would surely be very worthwhile and might even make a significant difference to some offenders. The Connect programme, which sought to do just that and was already operating in some prisons, was due to be introduced into St. Patrick\’s in 2003.

‘The biggest obstacle to achieving a

lot more is the daily regime of

St. Patrick’s’.

It never happened – instead it was withdrawn from even those prisons in which it was operating and most of the €46 million allocated to expanding the programme to all prisons appears to have been used to compensate for prison officer overtime.

Drug Rehabilitation in prison

A majority of those being committed to prison these days have a drug problem. While, again, successful drug treatment within the confined and isolating environment of prison is difficult to achieve, some prisoners are more than willing to accept help even within prison.

The only dedicated drug treatment service within the prison system is the 12-bed detox facility in the Medical Unit in Mountjoy prison. There is a waiting list to get into it. On completion of the detox, prisoners are transferred to the Training Centre where the possibility exists of continuing their rehabilitation by engaging in training programmes, sometimes linked to outside agencies. Apart from the Medical Unit, any drug treatment that takes place in prison happens despite the system. In Mountjoy, there is absolutely no drug-free space to support a person who wishes to tackle their drug problem; in Wheatfield, out of 320 cells, there are 16 cells available to those who become drug free. For prisoners in Dublin who want to become and remain drug free, their best option is to go to the Midlands prison, but the isolation from family and reduced possibility of visits is a serious obstacle. There are no counsellors to support them, no incentives to encourage them, no nothing!

The Minister is planning to create drug-free prisons by a policy that has already been tried in Scotland for ten years and is now being abandoned as a failure, namely random drug tests with punitive sanctions for testing positive. Presumably (but that may be a presumption we cannot make!) the Minister has consulted with the management personnel of the Irish Prison Service. However, 15 minutes consultation with anyone who knows the prison system or anyone seriously connected with the lives of prisoners could tell the Minister to get real. The Minister\’s proposal appears based on the premise that prisoners\’ drug use is simply irresponsible and selfish pursuit of pleasure. Many prisoners take drugs to forget their past, it is their only way of coping with childhood traumas or other overwhelming experiences that they find too difficult to bear. As one drug user said so eloquently: “Wouldn\’t it be wonderful to be able to ride away so fast that our memories could not catch up.”

Being alone in your cell for 19 hours a day ensures that your memories are your constant companion. Indeed, when imprisonment was first introduced as a penal sanction, the whole rationale for imprisoning people was precisely to keep them alone with their memories so that they could learn the error of their ways! People can overcome their addiction, they can learn other ways of coping, but they need intensive support to enable them to do so successfully. One-to-one counselling, group therapy and the realistic expectation that the future can be different from the past is necessary. Many prisoners are afraid to become drug-free in prison, because on release they may be returning to homelessness, boredome, or family problems and they know that if they relapse they may have to wait many months to regain their place on a methadone programme. To try to force people to abandon their learnt mechanism for coping with their problems without giving them alternative ways of coping is a recipe for increased tension within prisons, mental health problems, violence and self-harm.

The Minister\’s proposals, recently publicised, never mention harm reduction policies, although such policies are now part of mainstream drug programmes. A drugs policy that focuses exclusively on the elimination of drug misuse has long since been abandoned almost everywhere, as evidence-based research shows it to be much less effective. But the Minister\’s proposals to end the supply of drugs in prison is quite detailed with very specific policies – although many of them are already in operation in most Dublin prisons – with a few new policies such as random testing of 5-10% of prisoners each month. However, the proposals on helping prisoners to deal with drug misuse is remarkably short on specifics, such as is the Minister planning to introduce full-time, trained drug counsellors into prison and in what numbers relative to the number of prisoners who need them.

Models

A serious attempt at rehabilitation within prison would necessitate a serious programme of evidence-based research which would try to identify what works. However, there is little serious research taking place on prisons or indeed on the whole criminal justice system. The absence of hard information or evaluation of programmes ensures that political expediency and the imminence of the next general election inform decision-making. It is not that there are no models available which could provide a much more rehabilitative experience while in prison. Three examples, within our own system, come immediately to my mind.

a) Wheatfield Prison might become a juvenile centre.

When Wheatfield Prison was being considered, the Department of Justice scoured Europe to examine different prison structures. The design of Wheatfield Prison was based on the best model then available. It is divided into separate units containing 16 single rooms per unit. Each unit has access to its own small, open-air, grass space. In that model, prisoners have free association from 7.30 in the morning until 10 in the evening. They have the key to their own room so that they can lock it when they are out. They have unrestricted access to the open-air space. They cook their own meals, taking it in turns to cook for the whole group – thus each prisoner has to learn basic cookery skills.

They have to learn the social skills of group living, how to reach decisions by compromise, how to deal with conflict in a positive way, skills which they may not have possessed before coming into prison. Prison therefore becomes much more demanding, both for prisoners and for staff. Each day prisoners have to make decisions (something that is almost forbidden in the current prison regime) and prison officers need a whole new range of skills. In such a regime, education becomes a more attractive option, the prisoner knowing that they have many more hours in the day to associate with their friends and engage in other recreational activities such as hobbies or football.

b) Training Unit.

It has been shown time and again that rehabilitation programmes are more successful when offered outside of prison. Prison isolates young people who have already been isolated from main-stream society and this makes rehabilitation all the more difficult. Rehabilitation, when it must take place in prison, will be much more successful when linked to outside agencies and programmes.

The Training Unit provides a model which could be expanded and improved. There, prisoners can undertake a range of educational programmes within the prison and graduate to programmes or to work opportunities outside the prison, as they prove their commitment and reliability. Prisoners leave each day to go to the PACE workshops or other training courses or to employment. A serious commitment to rehabilitation would ensure that each young person committed to prison would be helped to draw up a personal plan with a graduated programme of working or training in the community. This only requires resources, a bit of effort, a little creativity and a willingness to take risks. Not of these appear to be available in the Department of Justice.

c) Temporary Release and Sentence Review.

Every young person in St. Patrick\’s that I know describes the place as a “kip”. They do not want to spend their day in idle boredom, but they have little choice. They are well aware of their illiteracy, their lack of education and absence of skills. They are often so proud of the certificates that they gain in prison and give them to me with strict instructions that I am to keep them in a safe place for them for when they get out. Many of them have never received a certificate in their life before. Sometimes the certificate merely states that they have participated in such and such a programme – it doesn\’t say that they have achieved anything, or even successfully completed the programme, but they are still so proud of it!

I have no doubt that a little encouragement, a daily regime that is supportive and a choice of meaningful educational or training opportunities would attract an almost 100% participation. As evidence of this, when judges handed down a sentence, with a review to be held after a given period of time in prison, many prisoners spent their time doing programmes which offered them certificates. They tried to accumulate as many certificates as possible to show the judge at the time of review. They wanted to show that they had spent their time in prison constructively and therefore deserved a chance. Despite the Supreme Court decision which effectively abolished sentence reviews, some legislation to re-instate them should be considered. They provided a wonderful, and necessary, motivation to use their time in prison constructively.

Similarily, temporary release, as part of a planned, personal educational or training programme, with links to outside agencies and services, could be an integral part of the management of offenders, providing a goal for the prisoner to achieve by means of an agreed set of achievements, with the knowledge that they will be recalled to prison if they fail to maintain their agreed programme.

The Context

I would suggest three reasons why rehabilitation for prisoners is not on the agenda. There is an ideology, consisting of three concentric circles, as it were, which militates against rehabilitation.

1. First, money spent on rehabilitation is considered wasted money. The primary criterion by which rehabilitation is judged is whether prisoners, on release, will re-offend. With a current 70% recidivist rate, to pour money into programmes for prisoners is seen as ineffective and therefore inefficient. However, with a paucacity of resources, an absence of programmes and no support on release, such a recidivist rate is only to be expected. Would a serious attempt at rehabilitation reduce recidivism? We don\’t know because it has never been tried. However, common sense suggests that it might. Research, if seriously undertaken alongside rehabilitative programmes, would inform the rehabilitiative process, making it more successful and cost effective. However, in my view, programmes of rehabilitation are first and foremost an issue of justice, an attempt to compensate for the failure of the educational and other systems which have been part of their lives before imprisonment. They ought not to be an optional add-on, to be provided, or withdrawn, at the political whim of a Minister, still less to be a pawn in a dispute between the Minister and the Prison Officers Association.

2. Secondly, over the past twenty years, there has been a growing movement away from rehabilitation of offenders to control of offenders, a movement that has been accelerated in the past ten years. Our criminal justice system has traditionally been characterized by a fine balance between the needs of the offender and the seriousness of the offence. Whether an offender receives a prison sentence or not, and for how long, depends not only on the seriousness of the offence, but also on the circumstances of that person – their childhood experiences, the level of deprivation they may have endured, issues such as addictions, mental health or low intelligence and whether they have shown any remorse or motivation to deal with these issues and so on.

Current policies have been shifting the balance away from the offender and on to the offence. It is a shift of focus from rehabilitation and re-integration of offenders to the control and exclusion of offenders. It is a shift from rightful intolerance of the behaviour of the offender to intolerance of the offender him/herself. Control measures such as more powers for the gardai, tougher legislation, restrictions on the right to bail, mandatory sentences, legislation to reduce the rights of the offender, and yet more new powers for the gardai have been introduced. Most recently, the proposed introduction of Anti-Social Behaviour Orders, which can see people being imprisoned for behaviour which was not, in itself, criminal behaviour, continues this trend. This shift towards excluding offenders from society has widespread public support. This support arises because we live in an increasingly fearful society with little sign of it getting better. As long as an excessive desire to control offenders who disturbs us, by excluding them and keeping them apart from us, is dominant, then the desire to change their behaviour and thus to re-integrate them will be pushed into irrelevance.

3. Thirdly, the focus on the economy that has driven Governments for the past ten or fifteen years appears to see money spent on anything other than the economy as a waste of resources. Those, like prisoners, who are of little value to the economy or who are likely to be of little value in the future, are seen as a drain on valuable resources. This is not entirely a cynical or hard-hearted perspective. The ideological justification for such a perspective is that the route out of poverty is through employment and so investing as much as possible into the economy is the most efficient way of lifting all boats. Diverting money into rehabilitative programmes for people who will be, at best, marginal to the economy is to slow down the process of eliminating poverty. However, in my view, this ideological position is deficient – while the Celtic Tiger has certainly lifted many people out of poverty, people who had never or rarely worked before in their lives, there remain those, including prisoners, who find it extremely difficult to secure employment, despite their best intentions and efforts to do so. Furthermore, some of those who do find employment can only find low-paid, insecure employment which does not lift them out of poverty. The need for direct investment into the lives of those on the margins to enable them to find a greater sense of fulfillment and self-esteem will always be necessary, particularly for those who will be marginal to the needs of the economy.

The carnage on our roads

A rehabilitative programme which offers offenders early release, which gives offenders the opportunity to engage with outside agencies and programmes and which makes their time in prison more meaningful and constructive requires a willingness by the Minister of Justice to take risks. Many will fail and the public are unforgiving when they do. The Department of Justice is one in which enlightened leadership can easily lead to political extinction. A major public awareness campaign would be required to demolish the myth that is so prevelant in the community that “longer sentences make communities safer.” A public awareness campaign would focus on the very obvious question: “What do communities want prisoners to be like when they leave prison?”

Most people have absolutely no idea of what life in prison is like and most people don\’t care. How do we change that? Some high profile persons, like Jeffrey Archer, who have unexpectedly found themselves in prison have subsequently talked about how the experience of prison has been a real eye-opener for them. They discovered, to their amazement and shock, a prison system that was destructive and dehumanising. They discovered that prisoners were much like themselves, a mixture of good and bad. And most telling of all, they discovered how their former apathy and lack of interest in what happens in prison had enabled them to preserve myths which they had grown up with and to insulate themselves, by their ignorance, from the uncomfortable questions which their time in prison opened up for them.

The carnage on our roads is an issue that generates much discussion and much criticism of the lack of effective political action to reduce it. Perhaps it is time to consider much more drastic action.

My suggestion is somewhat ironic in that I spend much of my time trying to keep people out of prison. But perhaps we should consider introducing mandatory 30-day imprisonment for drunk driving. Drunk drivers injure and kill far more people each year than joyriders – yet a conviction for joyriding will almost guarantee a prison sentence while a conviction for drunk driving will rarely do so. This minister seems to love mandatory sentences, so here is another opportunity for him. He is also building a brand new prison to expand the prison capacity so here is a way of making use of it. A mandatory 30-day prison sentence would send a strong message that drinking and driving is not acceptable in this society. As the deterrent effect of imprisonment is largely a middle-class concept imported into a criminal justice system which focuses predominantly on the poor, it might even work in reducing the number of people killed or injured on our roads, as many of the 9,500 people who were arrested for drink driving each year over the past four years are middle-class people who would never consider that prison was a possibility for them. If so many middle-class people were to experience the destructive, dehumanising effect of imprisonment, perhaps it might create a move for reform. If so many middle-class people were to live alongside, and get to know, prisoners from a very different social background, they too, like Jeffrey, might begin to question the myths that they have grown up with.

Is it only a coincidence that the most humane prison regimes in Europe are to be found in Scandanavian countries which have mandatory prison sentences for drunk driving?

Conclusion

I appreciate that a commitment to rehabilitation is a difficult issue for any Minister for Justice. The public doesn’t care what happens to prisoners, most don’t want their tax money spent on improving the lives of prisoners, money spent on rehabilitation shows few visible results (as you cannot see someone not committing a crime!) and the investment needed to really make a difference is very substantial. Nevertheless, rehabilitation is an issue of justice towards people who are amongst the most excluded and marginalized in our society and as such should be, as a matter of principle, a fundamental cornerstone of prison policy.

Fr Peter Mcverry, SJ