People are notoriously bad at assessing risk – we instinctively overestimate the likelihood of very scary events and underestimate the likelihood of familiar hazards. When this is combined with the power of gradual change, we end up collectively accepting situations that we would never rationally choose. The motorcar is the classic example: if we could objectively weigh the advantages (fast, autonomous personal transport) against the disadvantages (high risk of personal injury/death, environmental pollution, stress, dedicating large tracts of land to sole use of cars, etc.) we would likely come up with a very different system.

The modern Internet is another excellent example of our failure to assess and respond to risk. Discussions about risk and the Internet are often individualistic: What if my credentials are stolen? What if my search history is revealed? But we ought to be concerned about the wider impact. Our individual choices—however minor—add up to collective action.

Smartphones, social media, the Internet of Things: these tools have been broadly integrated into our lives with very little oversight. How are they changing our society? What risks have we (unwittingly) taken on with their adoption? Who is driving the change, and how do their priorities and incentives line up with those of broader society?

Our data is being collected in ways that were inconceivable 20 years ago. Indeed, the idea of “personal data” would have been irrelevant to most people then. This technological shift has brought about tremendous social, political, and economic changes which are still being processed: for example, in our attitudes to privacy, citizenship, and work. In this essay, I want to explore the digital transformation of capitalism and how it introduces a range of risks that could not have been imagined before the development of the Internet.

Privacy

We are all influenced by the old maxim “if you have done nothing wrong you have nothing to hide”, inclined to think that we’re too small to be interesting. Like dead skin cells, we spend our days shedding data.. Almost invisible, but it adds up to a lot of dust.

Individually, perhaps we are too small to be interesting, but our collated data reveals things that leave us open to manipulation. And in reality, we all do have something to hide. Firstly, we all have done something wrong, but we also organise surprises for loved-ones, or ponder questions that would be embarrassing or awkward if made known. Many of us have (for example) political opinions, family history, or medical history that could conceivably be used against us.

Privacy is also analogous to vaccination. National immunisation programs provide “herd immunity”: illnesses cannot take hold and reach epidemic levels, because so many members of the community are immune. Vulnerable people (for example those with suppressed immune systems) are protected because of the actions of the group. Similarly, a general expectation and protection of privacy is important for specific individuals who are interesting, such as whistleblowers and journalists. If Edward Snowden had not been able to act in secret, he could not have made the revelations that he did. There are other marginalised groups, whose race, gender, or non-mainstream lifestyles make them targets for bullying and harassment. By protecting everyone’s freedom to act in a reasonable amount of secrecy, we protect those who require secrecy to resist oppression. And so we all benefit, and we protect vulnerable members of our society. Solidarity with the marginalised is a way of preserving the common good.

The powerful have always dreamed of controlling the masses by close supervision, but it has never been such a realistic prospect as it is today. The new reality is that corporations have the means and the incentives to extrapolate a great deal of our internal state from the trail of data we leave as we surf. It has become a common occurrence to see an ad and think “how do they know I want that?” It is unlikely that this is a result of direct surveillance of your conversations, but neither is it a coincidence. In fact, you have left behind such a detailed web of data that algorithms can predict your desires. This is much, much worse.

At the same time, it is ever more difficult to live in the modern world without interacting with data-hungry websites. Social groups typically organise themselves on one of the big proprietary social media platforms. Therefore, the decision to not sign up isolates oneself. Almost every website is collecting huge amounts of data through technologies like cookies and Internet Protocol geolocation. The requirements introduced by the General Data Protection Regulation have highlighted the extent of this reality for many people, but hardly solved the problem.

Since mid-2019, almost anyone who applies for a US visa will be required to provide their social media usernames. If you’ve chosen not to use those websites because you don’t trust them, you risk looking abnormal, and thereby suspicious.

Smartphones offer amazing convenience, and social networks offer feelings of connectedness in an increasingly lonely world. The average smartphone user has a limited understanding of computer security. The average software developer has a limited sense of responsibility for the moral and ethical implications of their work. It can be more lucrative for corporations to play fast and loose with data. These factors have resulted in software that offers inadequate protections, and an erosion of our expectations of privacy online.

It is interesting to see what happens when an individual tries to challenge these new privacy norms. In 2013, Janet Vertesi decided to keep her pregnancy secret from the algorithms. No doubt she had many reasons for this decision, but as a sociologist of technology, one of them was scientific curiosity as to whether it was even possible. Her attempts to maintain her privacy often looked suspicious. When her husband tried to buy a large number of gift cards (in an attempt to anonymize their purchase of a buggy) he was confronted by a notification stating that the store “reserves the right to limit the daily amount of prepaid card purchases and has an obligation to report excessive transactions to the authorities.”

Our everyday choices are being closely observed and their implications analysed. And it is rapidly leading to a situation where attempting to protect your privacy looks like criminal activity.

Citizenship

Every day we voluntarily hand over information that previous generations recognised the need to guard, but who are we handing it to? Over the last few decades there has been a shift from government surveillance to surveillance by private enterprises, and where governments are undertaking digital surveillance, they are often outsourcing it to private companies.

Governments, at least nominally, act in the public interest. In modern liberal democracies, governments are expected to justify their actions in terms of the public good. Companies are not bound by such requirements; their primary responsibility is to their shareholders, including venture capitalists.

It is companies who are collecting and analysing every scrap of information they can about us. They are not doing it for ideological reasons: they are doing it to maximise profit, in part to play on our fears and sell us “solutions.” They are not subject to oversight in the way that public and academic bodies are. There are rarely ethics committees deciding whether their experiments are acceptable and where such oversight does exist, its remit is to serve the corporation’s best interests, which reduces to profit.

We have known for generations that the human mind is frighteningly hackable; bad actors with the required knowledge and access can (in limited, but significant ways) make us think and feel things that they choose. The ubiquity of smart devices, and the extent of the access we have granted them to our lives has led to unprecedented vulnerability to these techniques, both in terms of the number of people and the degree of access. And of course the large number of potential victims involved allows for selection of those most susceptible.

Cambridge Analytica have been accused of interfering in the electoral process in Trinidad (among other places). While the truth of such claims remains to be settled, it is a plausible story. It is conceivable that a bad actor with sufficient data and enough people’s attention could alter the outcome of an election.

Science fiction has long predicted the replacement of elected government by for-profit corporate power. Mega-corporations that war with each other through trade, espionage, and violence, unfettered by elected government, have featured in many a cyberpunk novel. As time goes on, these scenarios are seeming less and less fanciful. European governments have ceded a lot of power, and abdicated a lot of responsibility, through privatisation since the 1980s. That trend continues with outsourcing. Trans-national corporations are—if not dictating—heavily influencing public policy around the world. Governments are outsourcing their functions so that private companies are becoming the de-facto arbiters in law-enforcement, education, and health-care (among other things).

It is all too easy to imagine a kind of New Feudalism, in which our status as consumers and employees is more important than our status as citizens. And God help those who cannot get a prestigious job, or afford the right purchases.

The advertising industry is at the heart of the modern web. The spread of Internet access beyond military and university use came at a time when the provision of public utilities as a public good was being replaced by privatisation in the name of competition and efficiency. There was never any question that the Internet must be self-sustaining financially. While there are some websites with successful subscription models, it is undeniable that the majority of the money changing hands is paying for attention in the form of advertising.

In order to “target” ads, websites and platforms collect as much data as possible about individual users, and categories of users. The advertising industry has earned a reputation for ruthlessness. There’s no reason to believe they would hesitate to use amoral practices in analysing and deploying such data.

The advent of the Internet of Things (IoT) is extending privacy breaches and de-facto corporate power further into the “real world.” Media headlines about data concerns abound: landlords requiring all of their tenants to use insecure “smart” locks, deals struck between police forces and manufacturers of “smart” home security systems, facial recognition software being used on CCTV footage from the London Underground, or even at football matches. But in an atmosphere of fast-paced “disruption” very little seems to be done about it. As computer professionals like to joke: the “s” in IoT stands for “security”.

Of course, we would not want to overestimate the competence of these companies. To quote Maciej Cegłowski “… this talk of secret courts and wiretaps is a little bit misleading. It leaves us worrying about James Bond scenarios in a Mr. Bean world.” But if the owners of these vast databases are not handling them competently, then they are handling them incompetently. I’m not sure which is worse.

The ideal of a State where every individual has equal value and power is really not that old, and it certainly hasn’t been achieved yet, but it is well on its way to seeming quaint.

Work

The automation of human work has been accelerating since the dawn of the industrial revolution, if not before. Somehow, instead of increasing leisure time for everyone, those who have work are working longer and more intensely.

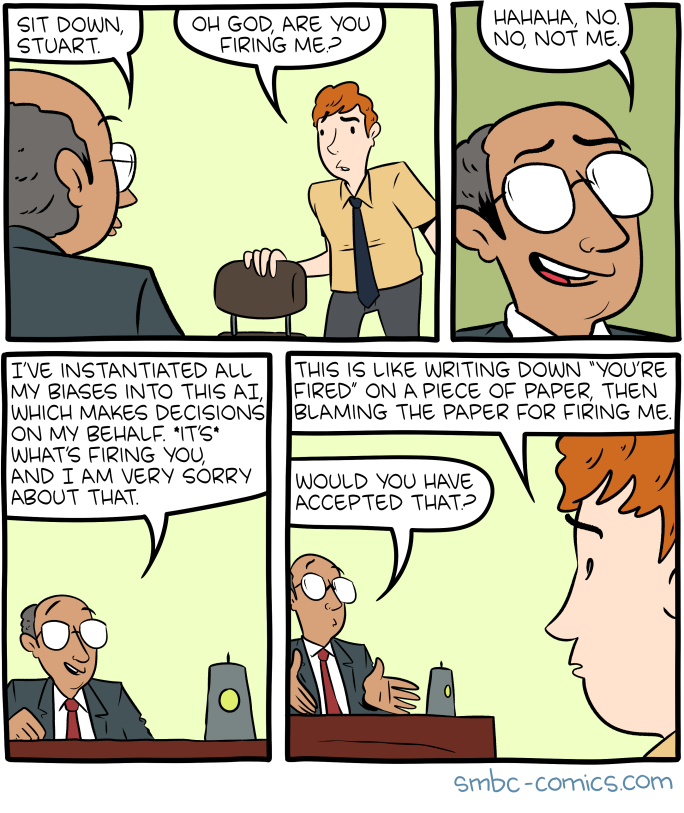

The advent of modern artificial intelligence (AI) promises—or threatens—to automate areas of work never before imagined susceptible. But these AI systems are not the impartial truth-tellers that some would have us believe. They are, in Cegłowski’s words “like money laundering for bias”. They embed prejudice and inequality behind an implacable “computer says “no”,” while accumulating the wealth that formerly supported the people doing the work.

As more and more of the productivity encompassed by Gross Domestic Product is produced by machines, the labour that can only be performed by human beings is becoming restricted to care work (which has always been undervalued within capitalism ) and the production of the data on which the algorithms depend.

If we are going to insist that profits be distributed by contribution, rather than need, we must begin to consider ways to compensate people for their production of data. Since these AI systems are completely dependent on inconceivably huge datasets, a strong analogy exists here with mining. There have been countless examples of communities in possession of natural resources, but no means to exploit them, who therefore received completely inadequate compensation from those who funded the digging. Artificial intelligence systems are as dependent on our data as the industrial revolution was on steel. To avoid the rampant inequalities of the first industrial revolution, this digital industrial revolution requires a new approach to sharing profits.

It can be hard for the lay-person to understand just how much information can be gleaned from a large enough database. Here is a small example: imagine an AI that had access to anonymised credit card histories. It could reveal that two credit-card users spent the weekend together, by discovering a series of pairs of transactions where the two cards were used in quick succession. Machine-learning algorithms are capable of analysing very, very large amounts of data and discovering patterns we could never have found. That data is key: they cannot function without it, and they cannot produce it.

The advent of high-speed communication technologies is also negatively impacting workers in another way, through the so-called ‘gig-economy’. Companies dole out work, piecemeal. They claim to be ‘disrupting’ markets but often they are side-stepping regulations which were introduced to protect workers.

If we allow the process discussed in the previous section—that is, the transfer of political power from elected governments to profit-making organisations—then we have no reason to expect a humanitarian solution to the burgeoning employment crisis. There is an argument that says the system requires consumers to function, and therefore the market will demand that consumers have the means to make purchases. We must recognise the risk entailed in trusting this as the basis of our collective response to the problem.

Work done by humans is subject to scrutiny in a way that work done by computers does not seem to be. There may be many psycho-socio-historical reasons for this, but among them is a pervasive belief in the objectivity of computers; an idea that they follow logic relentlessly, that their conclusions have a kind of mathematical purity. In fact, computers can only do exactly what they are told to do, whether or not the programmer understands what that is. As the old computer-science aphorism goes: garbage in, garbage out. The AIs that are being developed as part of this automation revolution will not overturn prejudice and systemic injustice unless we figure out how to tell them to.

The Irish Context

We need look no further than the introduction of the Public Services Card for an example of a system that poses a potential surveillance threat, which has been introduced in a haphazard way. It could well be that a national identity card, tied to a secure database containing medical records and similarly sensitive information, would be worth having. If we were to carefully examine the trade-offs between privacy and convenience, we might choose convenience. But that is not a debate which has been undertaken. Instead the government has tried to introduce the card using stealth and threats, for unclear motives, and without adequate security measures.

The card was introduced on a pilot basis in 2011, and the process of rolling it out across the nation began the following year. The order in which demographics were required to register for the card arguably targeted “groups who traditionally don’t have a particularly loud voice in the public sphere.” By 2017, Minister for Public Expenditure, Pascal Donohoe, was still claiming that the card was voluntary, despite the growing list of “consequences for not volunteering” (including having social welfare payments cut off, being unable to get a new driver’s licence, or replace a lost or stolen passport, or even to get your first passport or become a citizen). There were a number of red-flags raised by the project including a lack of transparency, a push to force uptake rather than making the card genuinely attractive to potential users, and scope creep.

Simon McGarr, a solicitor who has been a gadfly to successive Irish governments on several important topics, spent a lot of time challenging the introduction of the card, but it was the mistreatment of a pensioner that really pushed the problems with the card into the light. Her pension had been withheld for 18 months because she refused to register for the card unless and until she was shown proof that it was a legal requirement.

This card is just the latest in a long list of IT projects where the Irish government have failed to evaluate risk before pushing forward with ill-conceived systems: Pulse, PPARS , e-voting, and the Public Services Card all betray a deep failure to understand the complexity of, and risks associated with, modern technology. In each case, genuine concerns voiced by informed members of the Irish public were dismissed as scare-mongering. In each case, reality dawned gradually. But the Irish state has still not learned how to procure high-quality IT systems that provide adequate security safeguards for citizens’ private data.

Conclusion

Shoshanna Zuboff has coined the phrase “surveillance capitalism” to describe the context discussed in this essay. Her definitive book on this topic is an eloquent survey of the history and implications of the “darkening of the digital dream and its rapid mutation into a voracious and utterly novel commercial project.”

Zuboff cautions against ”confusion between surveillance capitalism and the technologies it employs.” We have taken on new risks with our new technologies—risks to the protections provided by our entitlement to privacy, to the sovereignty of our electorates, and to hard-won protections for workers—but it is not the technologies themselves that threaten us. It is the policies under which they are deployed, and the power structures we have allowed to be created around them.

I miss the Internet as it was in 1997. We told each other that “data wants to be free,” that the web was too wild a thing to be captured by commerce. We believed that we had discovered a new frontier that was so open and connected that it would change humanity for the better. We were naive to think that such a thing would develop on its own, unopposed, but perhaps if we are intentional, we can still make it happen.

Author: Margaret McGaley

For a pdf of this article, with footnotes, click here