David Moriarty

Introduction

We cannot allow the Mediterranean to become a vast cemetery! The boats landing daily on the shores of Europe are filled with men and women who need acceptance and assistance. (Pope Francis)1

During 2015, over one million migrants and asylum seekers risked crossing the Mediterranean Sea in unsafe boats in an attempt to enter the territory of the European Union. For many, though, this hazardous journey led not to the possibility of a new life in a place of safety and opportunity but tragically to their death: over 3,700 men, women and children, including in some cases several members of the same family, died by drowning while attempting to cross into Europe.

Asylum and immigration systems categorise people seeking entry from other states as ‘asylum seekers’, ‘refugees’, ‘forced migrants’, ‘economic migrants’. Yet it is important to remember that first and foremost these are people – people who share the same human condition that we do, who share the same hopes and dreams of a better life for themselves and their families. Behind the numbers and statistics are people with names and faces.

The response to the ongoing migrant and refugee crisis in Europe raises questions about the value systems which underpin European societies and the principles which the European Union espouses. Defining an appropriate and effective response is complicated by competing political narratives, the nature of forced migration and the scale of human need. European leaders face significant political difficulties in framing a coherent policy to address the immediate humanitarian needs arising out of the crisis as well as the structural causes underlying it.

The spontaneous gathering of German citizens at train stations to applaud arriving refugees, and the Uplift campaign where thousands of people in Ireland pledged an offer of accommodation for refugees,2 are examples of positive action being taken by communities on the ground in response to the crisis. On the other hand, the assaults in Cologne on the eve of 1 January 2016 highlight unacceptable behaviours and challenging attitudes among some sections of the recently-arrived refugee and migrant population – behaviours and attitudes to which host communities have to respond appropriately. In the long term, there exists the challenge of integration: how to ensure that all people living in EU Member States, long-term residents and those recently-arrived, can live together in dignity and mutual respect and participate fully in the life of the community, irrespective of their colour, creed or culture.

Statistics on Forced Displacement

The term ‘forcibly displaced’ refers to people who have been forced to move from their habitual place of residence because of conflict, generalised violence, persecution or other human rights violations. It includes people who have been displaced from their home but continue to live within the borders of their own state, and those who have crossed into another state where they have applied for asylum or have been accepted as a refugee or granted some other form of protection.

There has been a marked upward trend in the number of forcibly displaced persons in recent years. Data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), presented in Table 1 (overleaf), show that the total number of people worldwide officially recorded as displaced grew from 42.5 million in 2011 to 59.5 million in 2014. The number ‘newly displaced’ in 2014 was more than three times greater than in 2011. Table 1 also shows the increases in specific categories of displaced persons: refugees, including people in a ‘refugee-like situation’; asylum seekers; and internally displaced people. (Also included in the UNHCR totals for displacement – but not shown in Table 1 – are figures for a number of other specific categories of displaced persons: ‘stateless persons’; ‘returned refugees’; ‘returned internally displaced persons’; ‘others of concern’.) Statistics for the overall number of displaced persons in 2015 have not yet been published but a mid-year report by the UNHCR stated: ‘As the number of refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons (IDPs) continued to grow in 2015, it is likely that this figure has far surpassed 60 million.’3

European Union

The number of first-time applicants for asylum in EU Member States has been rising since 2008 but, as Table 2 below shows, the increase since 2013 has been very significant. During 2015, there was an unprecedented rise in applications, with over 1.2 million people claiming asylum in the EU ‒ over three times the number in 2013 and more than double the number in 2014.4 In the first two months of 2016, there were a further 168,175 first-time asylum applications.5

Transit Routes into the EU

A distinguishing feature of the current European refugee crisis is the number of people prepared to risk their lives to reach Europe by attempting the Mediterranean Sea crossing. Despite the hazardous nature of this journey, which often involves passage on grossly overcrowded vessels, including rubber dinghies and boats with unreliable engines, the number attempting to cross the Mediterranean has grown exponentially since 2010 (see UNHCR data, presented in Table 3 below). The number of refugees and migrants making this journey more than quadrupled between 2014 and 2015 – rising from just under 220,000 to over one million. A further 170,000 people arrived in Europe by sea during the first three months of 2016.6

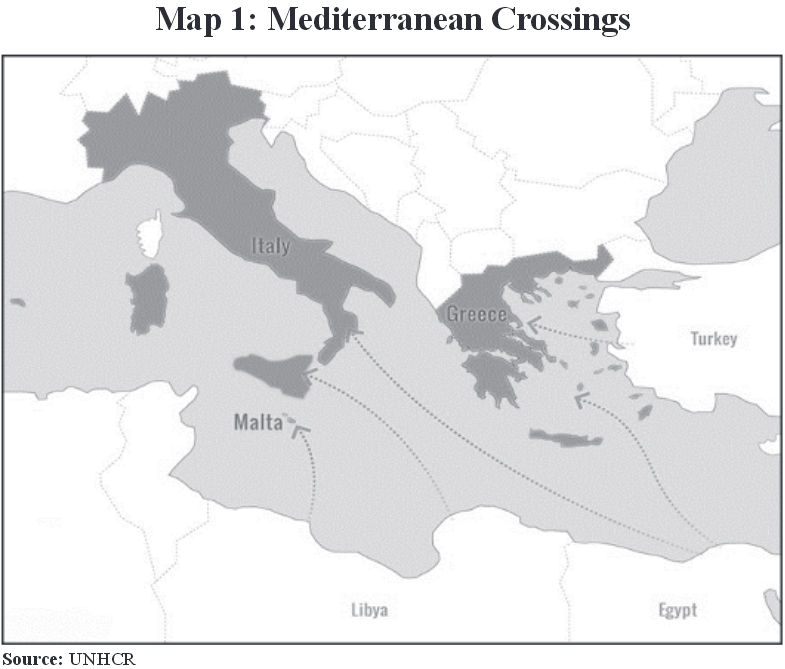

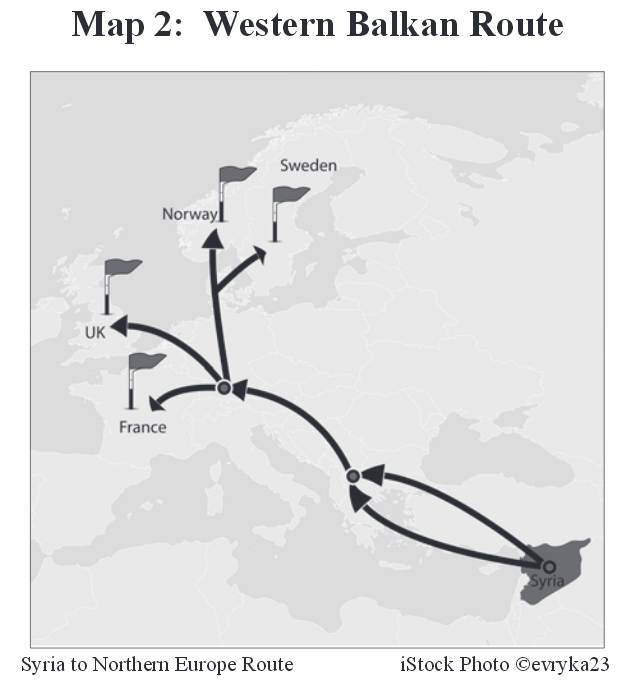

For asylum seekers and migrants, there are two main ways of entering Europe: via a Central Mediterranean route and via an East Mediterranean/Western Balkan route. Access to these routes often necessitates relying on smugglers, traffickers and other criminal networks.

The Central Mediterranean route encompasses the flow of people departing from North African countries – with Libya acting as a focal point – and arriving in Italy and Malta (see Map 1 above). The main groups traversing this route in 2015 were Eritrean, Nigerian and sub-Saharan nationals.

The East Mediterranean/Western Balkan passage involves first of all a sea crossing from Turkey onto one of the Greek islands – a distance of just a few kilometres. Since the beginning of 2015, this crossing, which is utilised primarily by Syrian, Afghan and Iraqi nationals, has become the principal route into Europe. Its increased significance as an entry point is indicated in the fact that that the numbers entering Greece in 2015 totalled 856,700, as compared to 43,500 in 2014.7 In other words, 85 per cent of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe in 2015 came via the East Mediterranean. In the first three months of 2016, an additional 152,152 people arrived in Greece.8

The East Mediterranean/Western Balkan route in fact entails entering, then leaving, and subsequently coming back into European Union territory. The initial entry, onto one of the islands of Greece and from there onto the mainland, is followed by a land route (the Western Balkan stage) from Greece through one of the former Yugoslav republics with the purpose of re-entering the EU. Originally, re-entry was via Hungary. However, following the huge increase in the number of people using this route in 2015, Hungary and then neighbouring states re-introduced border control measures. This culminated in a decision by the authorities in Macedonia in March 2016 to effectively close the country’s border with Greece.

Causal Factors

Syrian Conflict

The conflict in Syria has triggered one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises since World War II and is the principal driver of the current increase in global refugee numbers. There are estimated to be 13.5 million people in need of humanitarian assistance within Syria itself and, to date, the conflict has resulted in the internal displacement of approximately 6.5 million people and the registration of 4.6 million people from Syria as refugees in neighbouring countries (mainly Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey).9 It has been estimated that in excess of 250,000 men, women and children have lost their lives since the outbreak of violence in 2011.10

Despite mobilisation of over €5 billion in European aid for the region, and the efforts of numerous NGOs, including the Jesuit Refugee Service,11 the ongoing violence, destruction and threats to life continue to force thousands of people to flee Syria and cross into other states in search of safety and refuge.

The arrival of huge numbers of refugees from Syria into neighbouring states, such as Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq, has placed an unbearable strain on the resources of those countries and has stretched to the limit their capacity to manage inflows and offer refuge. These countries can no longer cope with the sheer numbers of people arriving and conditions in their refugee camps have been rapidly deteriorating. The situation in Lebanon is particularly acute: it is now host to 1.1 million refugees from Syria, roughly 25 per cent of the country’s original population. Refugees feel compelled to move on. In the words of one person aiming to make the journey to Europe: ‘It would be better to die with dignity crossing the sea than stay here [in Lebanon] and die slowly’.12

Poverty and Instability in Africa

The roots of the present crisis also include the political, social and economic ‘push factors’ driving people from Sub-Saharan Africa and other regions of the continent towards the North African departure points for Europe.

The major land routes that facilitate the migration flows towards North Africa are:13

• From Central and West Africa, mainly through Senegal, Mali, and Niger;

• From East African countries, in particular Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia, through Sudan and Chad.

From the early 1990s, thousands of people each year attempted to cross into Europe from North Africa, via the Central Mediterranean Sea route. Since the end of 2010, however, the political and economic upheavals occurring in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya have had the effect of greatly increasing flows to Europe.

In Libya, the political vacuum which followed the overthrow of General Muammar Gaddafi in 2011 resulted in the descent of the country into political instability, violence and lawlessness. A security void created by weak state institutions, in particular the military and police, has been exploited by militia who have assumed control of large swathes of Libyan territory, including sections of the coastline. In these circumstances, and given its strategic geographical position, Libya has become the focal point for sea crossings into Europe from North Africa, with smuggling and human trafficking operations growing exponentially.

In July 2014, a report by JRS Europe and Jesuit Migrant Service Spain drew attention to the particular situation in the area of Morocco adjoining Ceuta and Melilla, two Spanish-owned enclaves on the North African Mediterranean coast. Gaining access to either enclave means, in effect, entering EU territory and so hundreds of migrants have congregated close to their borders in the hope of being able to make the crossing. The reality is that few succeed and the vast majority suffer greatly in the harsh and even dangerous living conditions they are forced to endure.14

The net result of the multiple ‘push factors’ operating in many African nations is that hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees have congregated in North African states with a common goal of gaining access to Europe and to a better life for themselves and their families. In 2014, Frontex, the European border agency, recorded 170,664 detections of illegal border crossings from a North African departure point and via the Central Mediterranean route; in 2015, a further 153,946 detections were recorded.15 As long as the structural economic and political failings that drive forced migration across the African continent remain, the strong flow of people towards Europe along this route will continue.

EU Response

The EU has been reactive and divided in its response to the migrants and asylum seekers who have been arriving at its borders and transiting Member States in ever-greater numbers in the past few years. The crisis has revealed a sharp divergence of views among Member States, and especially between Western and former Eastern bloc states, in relation to how the EU should respond. The terrorist attacks in Paris (November 2015) and Brussels (March 2016) have added a security dimension to EU policy considerations and have resulted in heightened concerns among politicians and the public about who might be travelling in refugee and migrant flows.

European Agenda on Migration

During 2015, the EU agreed the ‘European Agenda on Migration’ as the primary mechanism for responding to the unfolding crisis. This initiative, originally announced in May16 and enhanced in September 2015,17 attempted to establish a framework for a comprehensive approach to migration management.Some of the concrete actions agreed were:

• In terms of relocation within the EU, 160,000 people in clear need of international protection were to be relocated over two years from the Member States most affected (Italy and Greece) to other EU Member States;

• In terms of resettlement from countries outside the EU, 22,000 recognised refugees from countries neighbouring Syria were to be resettled across EU Member States over two years;

• EU funding was to be mobilised in support of the Member States most affected by the arrival of large numbers of migrants;

• The EU was to triple its presence at sea;

• There were to be significant increases in aid for Syria and Africa.

However, this package of measures by the EU has so far been ineffective due to political differences and lack of sufficient commitment.

Political Division: The EU response has been largely characterised by division in approach and values. At the policy level, unilateral actions by Member States have deepened divisions. Germany initially adopted an open borders approach by effectively suspending the operation of aspects of ‘the Dublin system’ – the mechanism for determining which EU Member State should be responsible for examining an application for asylum lodged within the EU – in order to facilitate access by Syrian refugees. In contrast, the authorities in Hungary and several other Member States have been steadily closing their country’s borders by erecting fences to control the influx of refugees and migrants.

The depth of political division in the EU was starkly highlighted in September 2015 when decision by qualified majority was needed in order to force through mandatory relocation quotas, in the face of strong opposition from several Eastern European Member States. The values debate has centred on the cultural and religious traditions of arriving refugees and migrants. Some Member States have warned that the influx is a threat to the values, including those rooted in Christianity, which underpin European culture and politics. In sharp contrast, Pope Francis has argued that differences of race, national origin and religion can be a gift and a source of richness – something to welcome, not fear.

Insufficient Scale: The combined commitments under the EU relocation and resettlement schemes have the capacity to reach fewer than 100,000 persons annually over a twenty-four month period. This is not even a tenth of the refugees and migrants who crossed into Europe by sea during 2015. It is abundantly clear that, against the scale of human need represented by the current crisis, the agreed common response of the EU is severely inadequate and so responsibility will continue to be inequitably shared across Member States.

Lack of Implementation: In order to qualify for protection and relocation under EU programmes, individuals are required to first apply for asylum in either Italy or Greece. This, however, has not been happening. On the one hand, there are serious inadequacies in the reception infrastructure, services and registration procedures in pressure points. This is particularly so in the case of Greece, a country of just under 11 million people, which for several years has been experiencing enormous economic problems but which, because of its geographical location, has become the entry point for the great majority of refugees and migrants now arriving in Europe. On the other, there is the reality on the ground that many refugees seek to reach their preferred country of destination directly rather than risk a ‘relocation lottery’ which may result in their being moved to a location other than the one preferred.

The fact is that, as of 15 March 2016, out of a proposed target of 160,000, just 937 people had been relocated. Only eighteen Member States had pledged to relocate people from Greece and nineteen Member States had pledged relocations from Italy. The total number of places formally pledged was just 3,723.18

The EU–Turkey Agreement

On 18 March 2016, the European Council announced details of the EU–Turkey agreement, an escalation in Europe’s response to the crisis and one which includes the overarching aim of ending ‘irregular migration from Turkey to the EU’.19

The negotiation of this agreement was not an isolated event but rather the culmination of consistently closer cooperation on the migration issue between the EU and Turkey over the preceding months.

The three main components of the deal are:

• Return of all irregular migrants crossing from Turkey onto the Greek islands.

• Resettlement of Syrians on a one-for-one basis, i.e., for every Syrian returned to Turkey from one of the Greek islands, another Syrian from Turkey is to be resettled in the EU. In this process, priority will be given to Syrians ‘who have not previously entered or tried to enter the EU irregularly’.

• Prevention of the opening up of any new sea or land routes for illegal migration from Turkey into the EU.

At the time of writing, the full scope, impact and consequences of this agreement cannot be adequately evaluated. However, there are significant legal, procedural and operational challenges facing the deal. In addition, serious questions remain about its compliance with EU law and, critically, the potential of the one-for-one procedure to act as an inherent barrier to accessing fair asylum procedures in the EU.

Returns to Turkey have already commenced.20 Another immediate consequence of the agreement has been the scaling back or suspension of services for refugees and migrants on Greek islands by a number of organisations, including UNHCR and NGOs such as Oxfam and Médecins Sans Frontières. They have taken this action on the basis of their concern that the system now in operation means that facilities on these islands have been effectively transformed into detention centres.

Additional Policy Challenges

In the context of the failings in the EU response, two central planks of EU policy have been increasingly challenged.

Firstly, the Schengen Agreement, which underpins the free movement of people across EU internal borders, is under threat as a result of Member States reintroducing border controls.

Secondly, the Dublin system (i.e., the mechanism for determining which Member State is responsible for processing an asylum application) has proven unfit for purpose in ensuring an equitable distribution of responsibility across Member States.

In a Communication in April 2016 on proposed EU asylum policy reform, the European Commission identified two options for amending the Dublin system.21 The first suggests preserving the existing apparatus and supplementing that system with a corrective fairness mechanism (similar to the EU relocation scheme) which could be triggered at times of mass inflows. The alternative proposal is to replace the existing structures by creating a new system, where allocation of responsibility would be determined on the basis of a distribution key (according to a Member State’s size, wealth, etc.).

Ultimately, fundamental reform of the Dublin System is unavoidable, if there is to be a more equitable sharing of responsibility for the reception of those seeking protection, for the determination of protection applications, and for the integration of those who remain in Europe. The options outlined by the European Commission make reference to expressions of solidarity, to taking into account the economic strength and capacity of Member States, and to the need for emergency mechanisms at times of crisis. However, if any new structures are to operate efficiently they must not only secure the agreement of Member States but also, and critically, foster the trust and cooperation of asylum applicants and address the coercive dimensions associated with the Dublin system. A study for the European Parliament, published in 2015, highlighted that avoiding excessive coercion of asylum seekers and refugees is key to ensuring workable asylum systems and effective mechanisms for allocating responsibility between states.22

Finally, there is need to acknowledge that the lack of safe and legal ways of entering Europe (such as enhanced resettlement, family reunification, humanitarian visas and ‘refugee friendly’ student and labour market schemes) is a major factor influencing the huge increase in the number of asylum seekers attempting perilous Mediterranean Sea crossings.

There are also cohorts of people seeking to enter Europe who do not qualify for international protection but are nevertheless deserving of refuge, including those forcibly displaced by dire poverty, environmental degradation or other life-threatening circumstances. Thus, in addition to increasing safe and legal routes to enable people seek protection in the EU, there is need for an increase in legal avenues for migration

The Irish Response

In response to the crisis, the Irish Government, in September 2015, agreed to establish the ‘Irish Refugee Protection Programme’ and made a commitment to accept 2,900 people under EU relocation and resettlement programmes.23 This was in addition to a commitment made in July 2015 to accept 600 people as part of an EU relocation programme, as well as a promise to admit 520 people under an EU resettlement programme. In all, therefore, the Irish Government has made commitments to accept around 4,020 persons under the EU relocation and resettlement programmes and has stated that it expects these numbers to be augmented by family reunifications.24

The key ambitions of this nascent programme are: the creation of a network of Emergency Reception and Orientation Centres; assessments and decisions on refugee status to be made within weeks; special attention to be given to the plight of unaccompanied children; the provision of additional budgetary resources; and the establishment of a cross-departmental taskforce to coordinate and implement the programme.

In a context where the focus is, understandably, on the crisis emanating from the arrival of large numbers of people into Europe, it is important that the needs of asylum seekers already in the application process in this country, especially those residing long-term in Direct Provision, are not forgotten. The number of new asylum applications in Ireland in 2015 was twice that in the previous year, having increased from 1,448 in 2014 to 3,276 in 2015.25 Irish relocation and resettlement initiatives under EU programmes represent commitments which are additional to dealing with these applications.

Ensuring consistent, equal and fair determination processes and procedures which operate regardless of how protection applicants arrive in Ireland is critical.

While the proactive response indicated in the Irish Government’s statement in September 2015 was broadly welcomed, key questions remain, including:

Scale of Response: Can and should Ireland do more? A joint briefing paper, Protection, Resettlement and Integration, issued by a number of Irish NGOs, including JRS Ireland, contends that the country has the capacity to respond much more generously to the scale of human need presented by the arrival in Europe of hundreds of thousands of refugees and migrants. The paper advocates that the Government should: ‘Keep the number of relocated and resettled people under review with a view to increasing the number to approximately 0.5% of the population (22,000)’.26

Accommodation: How will the proposed Emergency Reception and Orientation Centres for the accommodation of those relocated or resettled under EU programmes differ from the existing Direct Provision centres? Will the opening of these centres lead to a two-tier accommodation system for people seeking protection in Ireland?

Prioritisation: Will applications for protection made under the European relocation scheme be given priority in the determination process? If so, what will be the impact on the length of time taken to process the claims of existing applicants, many of whom have already spent years in the system? Is there a danger that there will emerge a two-tier case processing system for persons seeking protection in Ireland?

Resources: The Final Report of the Government-appointed Working Group on the Protection Process, issued in June 2015, identified the elimination of backlogs and the provision of additional resources for case processing as key requirements for the reform of the Irish protection system.27 Will sufficient additional resources now be provided not only to implement the recommendations of the Working Group but to fulfil the new commitments arising out of the EU relocation and resettlement programmes being operated under the ‘Irish Refugee Protection Programme’?

Integration Planning: What steps will be taken to ensure that there are adequate resources to meet the education, English-language acquisition, welfare and employment needs of people granted protection status under EU programmes and of people given status under the existing protection application system, and thus exiting Direct Provision?

The key to Ireland responding appropriately and generously to the crisis is to have a fair and transparent asylum process that is operating efficiently and producing final determinations in a timely manner. The introduction of a ‘single procedure’ for determining protection applications, under the International Protection Act 2015, is a welcome first step.28 However, its effectiveness in eliminating excessive delays in the asylum system will be undermined if the Government fails to fully implement the key recommendations of the Working Group on the Protection Process.

At the time of writing, it is unclear to what extent the EU–Turkey agreement will impact on the approach adopted by Ireland in response to the crisis. However, regardless of the potential ramifications of that deal and any operational difficulties that may exist, there is nothing to prevent this country from significantly enhancing its own resettlement programme or unilaterally exploring and scaling up other safe and legal ways to facilitate greater access to protection in the State. Fundamentally, Ireland could and should be doing more in response to the vast scale of human need arising from the current crisis.

Response by Individuals

In many EU Member States, including Ireland, there has been considerable public goodwill and support for refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea into Europe, especially those fleeing Syria. Individuals and communities have pledged accommodation, time and skills to assist refugees being resettled or relocated. Following the call from Pope Francis for religious communities to play a role in responding to the refugee crisis, there has been dialogue among faith-based stakeholders and church groups as to how to welcome and assist refugees in a coordinated and effective way.

It remains the case, however, that due to the dynamic nature of the crisis, and its enormity and complexity, individuals may be unsure as to what are the most effective ways they can respond to the urgent humanitarian needs of refugees and migrants arriving in Europe. Concrete actions which individuals might take include:

• Donate: Support Jesuit Refugee Service International appeals (for example, its ‘Urgent Appeal for Syrians’ or ‘Give a Warm Welcome to Refugees in Europe’ or ‘Mercy in Motion’ appeals). These appeals are for funds to provide food, blankets, first aid, other basic necessities, and educational services for refugees.29

• Volunteer: Contact JRS Ireland, the Irish Red Cross or local parish and community groups to pledge services or time in order to welcome victims of forced displacement living in Ireland.

• Advocate: Urge politicians from across the political spectrum to not only work for improvements in the State’s protection process, including the Direct Provision system, but show support for Ireland making a greater contribution to the EU response to migrants and refugees arriving in Europe.

Conclusion

The unprecedented scale of the refugee and migrant crisis casts a shadow over the European Union that is unlikely to fade in the foreseeable future. Stark divisions among EU Member States, the ad hoc implementation of border control measures, and the inadequacy of policy responses adopted to date threaten the very foundations of the European project. But it must not be forgotten that failures in the response also threaten the lives of thousands of refugees and migrants.

Peter Sutherland, the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Migration and Development, has contended that the EU, with a population of just under 510 million people, should have been able to welcome the arrival of a million refugees ‘had the political leadership of the member states wanted to do so and had the effort been properly organised’. Instead, he said, ‘ruinously selfish behaviour by some members has brought the EU to its knees’.30

In the immediate future, the EU must find solutions which save lives by diverting people from perilous sea crossings and ensure a fair and equitable sharing across Member States of responsibility for receiving and processing applications for protection. In addition, it must contribute to efforts to address the root causes of the crisis.

Other fundamental questions arise:

• How will the arrival of large numbers of refugees and other migrants be managed to ensure the founding values of Europe are strengthened and not undermined?

• What steps must be taken to foster integration and avoid the marginalisation of refugee and migrant cohorts and the risk of radicalisation?

• How do we, as European citizens, embrace difference and welcome the stranger?

In conclusion, it is worth reflecting on the words of the President of the Conference of European Jesuit Provincials, John Dardis SJ:

While asylum and migration are certainly complex issues, the simple fact is that, in the end, people are dying. At this defining moment, we can and we must reach out.

… There has been debate in recent years about the Christian roots of our continent. This is a time to show that this is not a debate only about language and terminology. Let us together try to help our continent and our societies move forward, to show that we are Christian not just in name but in fact, to show our love ‘not just in words but in deeds’.31

Notes

1. Address of Pope Francis to the European Parliament, Strasbourg, France, Tuesday, 25 November 2014. (http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/speeches/2014/november/documents/papa-francesco_20141125_strasburgo-parlamento-europeo.html)

2. ‘Over 6,000 people pledge to home refugees as humanitarian crisis worsens’, the journal.ie, 4 September 2015. (http://www.thejournal.ie/pledge-a-bed-uplift-campaign-2310752-Sep2015/)

3. UNHCR, Mid-Year Trends June 2015, Geneva: UNHCR, p. 3. (http://www.unhcr.org/56701b969.html)

4. (i) Eurostat, ‘Asylum and First Time Asylum Applicants by Citizenship, Age and Sex, Annual Aggregated Data’. (http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do); (ii) Eurostat, ‘Asylum in the EU Member States: Record number of over 1.2 million first time asylum seekers registered in 2015’, Eurostat News Release, 44/2016 – 4 March 2016.

5. Eurostat, ‘Asylum and First-Time Asylum Applicants – Monthly Data’. (http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do)

6. UNHCR, Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean, Information Sharing Portal hosted by UNHCR, data as of 1 April 2016. (http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

7. UNHCR, Greece Refugee Emergency Response, Update #8, 29 November–31 December 2015. Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean, Information Sharing Portal hosted by UNHCR. (http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/country.php?id=105)

8. UNHCR, Refugees/Migrants Emergency Response – Mediterranean, Information Sharing Portal hosted by UNHCR, data as of 1 April 2016. (http://data.unhcr.org/mediterranean/regional.php

9. European Commission, Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (ECHO), ECHO Factsheet: Syria Crisis – March 2016. Brussels: Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection, 2016. (http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/aid/countries/factsheets/syria_en.pdf)

10. United Nations Security Council estimate, August 2015. See: UN Security Council, ‘Alarmed by Continuing Syria Crisis, Security Council Affirms Its Support for Special Envoy’s Approach in Moving Political Solution Forward’, 7504th Meeting, 17 August 2015. (http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sc12008.doc.htm)

11. In response to immediate humanitarian needs, the Jesuit Refugee Service is present in Syria, distributing emergency relief and providing educational activities to promote reconciliation and peaceful co-existence. In Damascus, Homs, and Aleppo, staff and volunteers have assisted an estimated 300,000 people through the provision of food support, hygiene kits, basic healthcare, shelter management and rent support.

12. Anecdotal evidence from development workers in the region.

13. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Smuggling of Migrants Into, Through and From North Africa: A Thematic Review and Annotated Bibliography of Recent Publications,Vienna: UNODC, 2010, p. 13.

14. Jesuit Migrant Service Spain and Jesuit Refugee Service Europe, Lives at the Southern Borders – Forced Migrants and Refugees in Morocco and Denied Access to Spanish Territory, Brussels: JRS Europe, 2014. (https://www.jrs.net/assets/Publications/File/lives_at_the_southern_borders.pdf)

15. See: Frontex, FRAN Quarterly, Quarters 1, 2, 3 and 4, 2015, Warsaw: Frontex. (http://frontex.europa.eu

16. European Commission, A European Agenda on Migration, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 13.5.2015 COM(2015) 240 final. (http://ec.europa.eu/lietuva/documents/power_pointai/communication_on_the_european_agenda_on_migration_en.pdf)

17. European Commission, ‘Managing the Refugee Crisis: Immediate operational, budgetary and legal measures under the European Agenda on Migration’, Press Release, Brussels, 23 September 2015. (http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5700_en.htm)

18. European Commission, First Report on Relocation and Resettlement, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, Brussels, 16.3.2016 COM(2016) 165 final.

19. European Council, ‘EU-Turkey Statement’, 18 March 2016. (http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement/).

20. Damian Mac Con Uladh, ‘Migrants deported to Turkey from Greece under EU deal’, The Irish Times, 4 April 2016. (http://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/migrants-deported-to-turkey-from-greece-under-eu-deal-1.2597583)

21. European Commission,Towards a Reform of The Common European Asylum System and Enhanced Legal Avenues to Europe, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council, Brussels, 6.4.2016 COM(2016) 197 final.

22. Elspeth Guild, Cathryn Costello, Madeline Garlick, Violeta Moreno-Lax and Sergio Carrera, Enhancing the Common European Asylum System and Alternatives to Dublin: Study for the LIBE Committee, Brussels: European Parliament, 2015. (http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analysis)

23. Department of Justice and Equality, ‘Government approves ‘Irish Refugee Protection Programme’’, Press Release, 10 September 2015. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/PR15000463)

24. Ibid.

25. Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner, Monthly Statistical Report, January 2016. (http://www.orac.ie)

26. Protection, Resettlement and Integration: Ireland’s Response to the Refugee and Migration ‘Crisis’, Briefing Paper by NGOs, Dublin, December 2015. (http://www.jrs.ie/hearing-voices/policy)

27. Working Group to Report to Government on Improvements to the Protection Process, including Direct Provision and Supports to Asylum Seekers, Final Report, Dublin: Department of Justice and Equality, 2015. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Report-to-Government-on-Improvements-to-the-Protection-Process-including-Direct-Provision-and-Supports-to-Asylum-Seekers)

28. The introduction of a ‘single procedure’ for processing applications for protection was the most far-reaching provision of the International Protection Bill 2015, which was signed into law on 30 December 2015. A ‘single procedure’ means that an application for protection is simultaneously assessed on whether it meets the requirements for refugee status, some other form of protection, or leave to remain. By contrast, a sequential determination process, in operation in Ireland up to the coming into force of the new legislation, first assesses eligibility for refugee status; if that is not granted, then the person’s eligibility for some subsidiary form of protection is assessed.

29. Donations to the work of the Jesuit Refugee Service can be made online. (https://en.jrs.net/donate)

30. Remarks by Peter Sutherland, ‘Migration – The Global Challenge of Our Times’, Michael Littleton Memorial Lecture, 17 December 2015, broadcast RTE Radio 1, Saturday, 26 December 2015; reported in: Ruadhán Mac Cormaic, ‘Selfishness on refugees has brought EU ‘to its knees’’, The Irish Times, 26 December 2015. (http://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/selfishness-on-refugees-has-brought-eu-to-its-knees-1.2477702)

31. John Dardis SJ, President, Conference of European Jesuit Provincials, ‘The Refugee Crisis in Europe – Call for our Response’, Letter to Major Superiors of Europe about the current refugee crisis in Europe, 7 September 2015. (http://www.jesuits-europe.info/news/2015/nf_15_09_06.htm)

David Moriarty is Policy and Advocacy Officer, Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland