Eugene Quinn, April, 2011

Introduction

The maintenance of a low tax regime was a key tenet of national policy during the years of Ireland’s economic boom. However, there were also demands from many quarters for improved public services and for greater protection for the most vulnerable. For a time, Ireland appeared to achieve the impossible – remaining a low tax economy while spending ever greater amounts on public services. It was a mirage.

International events in 2008 lit the fuse to a crisis that would ultimately overwhelm the State’s finances. But at the heart of our woes was not the international financial crisis but a home-grown problem. Ireland found itself facing a double-sided structural deficit problem, in which the crash in tax revenues was not being mitigated by equivalent reductions in public spending. In particular, the massive growth in unemployment represented a dual blow, with the consequent reduction in tax revenue occurring alongside a huge increase in the number of people dependent on the State for social welfare payments.

At the same time, Ireland found itself engaging in massive and unforeseen expenditure in order to save its banking sector. Having guaranteed all the domestic banks’ liabilities on 30 September 2008, Ireland has been facing a mounting bill ever since.

The escalating cost of bailing out the banks, combined with the massive structural deficit in the public finances, caused international bond markets to lose faith in Ireland’s capacity to repay its debts. In November 2010, Ireland came to a point of no return when the cost of raising funds on international markets reached prohibitive levels. The result was the humiliating experience of the country being forced to accept a bailout from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The arrival of the IMF sounded the final death knell of the Irish economic ‘miracle’.

A condition of the EU/IMF funding is that Ireland is placed in a four-year fiscal straitjacket that will require the public finance deficit (that is, the difference between taxes raised and public expenditure by the State) to be lowered to 3% of GDP – or in monetary terms, to be reduced by €15 billion – by 2014. (The Fine Gael/Labour Party Programme for Government sets 2015 as the date for achieving this target.1)

The 2011 Budget, which ‘frontloaded’ €6 billion of the adjustment through tax increases and expenditure cuts, signalled the beginning of the process of achieving this target – and of the period of austerity that will inevitably accompany it. Much of the debate in the recent General Election centred on how the remaining €9 billion (or more) reduction will be sourced. Will it be from increases in taxation or cuts in public expenditure?

Erosion of the Tax Base

The Irish tax system is constructed on the basis of a number of main tax categories (or heads). Income of employees is taxed on a pay-as-you-earn (PAYE) basis and that of the self-employed is based on a self-assessment of their income. Dividends and rents are taxed as income. Capital Gains Tax is levied on appreciation in asset values. Stamp Duty is paid on transactions, such as property sales. Inheritances are subject to Capital Acquisition Tax. Company profits are taxed at a standard rate of corporation tax. In addition, a large proportion of central government tax revenue is derived from value added tax (VAT), excise duties and other taxes on consumption.

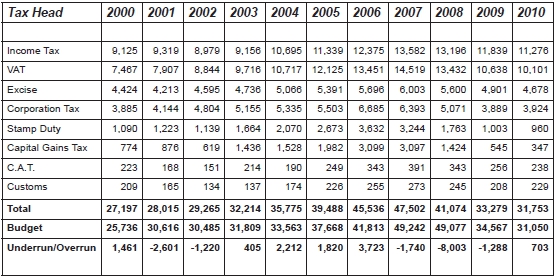

During the Celtic Tiger years, Ireland significantly eroded its tax base; the degree to which this was unsustainable became all too evident with the collapse in tax revenues in 2008. Table 1 tracks the movement in net revenue receipts from 2000 to 2010. It is notable that, up until the crisis in 2008, there were Exchequer surpluses in each year except 2001 and the General Election years 2002 and 2007.

| Table 1: Net Exchquer Returns 2000-2010 (€m.) |

|

| Source: Revenue Commisioners,Annual Reports 2000 to 2009 andHeadline Results for 2010 |

Income Tax

For more than a decade, Government policy aimed to remove a greater proportion of those on lower incomes from the income tax net. Since 2000, income tax bands have widened by 105% for a single person and married couples with both earning. (In comparison, consumer price inflation in the period 2000 to 2010 was 35%.2) Income tax credits have increased by 92% since their introduction in 2001. Standard and higher income tax rates fell from 26% and 48% in 1997/98 to, respectively, 20% and 41% in 2007. In the period since 2000, the combined effect of these changes was that, for PAYE earners, the entry point to income tax rose from €7,238 to €18,300.

The outcome of the process of reducing income tax liability is noted inThe National Recovery Plan 2011–2014, which points out: ‘… the proportion of income earners exempt from income tax increased from 34% in 2004 to an estimated 45% in 2010. It is now estimated that for the current year, 42% of income earners will pay tax at the standard rate and just 13% will be liable at the top rate’.3

However, the outcome of tax policy during the years of the economic boom wasn’t only that people who were less well-off paid less, or no, income tax: an array of property related tax breaks, to which there was widespread recourse, meant that many on higher incomes were able to minimise their income tax liability.

In his Budget speech in December 2010, the then Minister for Finance, Brian Lenihan TD, stated:

Our income tax system, as it stands today, is no longer fit for purpose. At one level, too few income earners pay any income tax. This year, just 8%, earning €75,000 or more, will pay 60% of all income tax while almost 80%, earning €50,000 or less will contribute just 17%. At another level, too many high earners have opportunities to shelter their income from tax. We must address both these structural defects.4

Inequities in the system

Inequities in the income tax system can be illustrated by outlining the experience of a ‘captive’ PAYE worker who has been paying tax since the mid-1970s. This worker would have started his or her career subject to a crippling and penal income tax regime, with marginal income tax rates as high as 70%. Over time, the income tax regime became progressively less onerous due to Government policy during the Celtic Tiger years, leading to the kind of reductions in income tax already noted. However, recent budgets have seen income tax levels rise once more.

The National Recovery Planproposes further cuts in tax credits and reductions in tax bands. The Fine Gael/Labour Party Programme for Government promises there will be no increases in income tax.5However, this is likely to prove hard to deliver, especially if the economy does not hit the target growth rates – rates which many commentators feel are unrealistic.

The compliant PAYE tax payer might well feel aggrieved at the ways fellow taxpayers reduced, legitimately avoided, or illegitimately evaded income tax throughout the period since the 1970s:

Self-Employed and Farmers: PAYE taxpayers shouldered the major part of the tax burden because they were captive. Self-assessment allows self-employed individuals latitude to manage income in a tax efficient wayviacapital allowances (for example, purchase of machinery), deductible expenses for the running of their business, and the timing of realised gains.

Tax Amnesties:Non-compliant taxpayers in the late 1980s and early 1990s were ‘rewarded’ for earlier evasion by being able to avail of amnesties from prosecution and liability to interest penalties. The 1993 amnesty included not only an amnesty from interest and prosecution but introduced a special 15% tax rate for individuals with arrears in income tax, Capital Gains Tax or levies. In each amnesty, there was a windfall for the Exchequer – the 1988 amnesty, for example, brought in more than five times the projected yield of €100 million6– pointing to widespread previous evasion.

Tax Breaks and Shelters:High income earners can avail of the best tax advice and take advantage of tax breaks and shelters. While many tax breaks were introduced initially to support important social goals, such as the regeneration of urban areas, they were retained long after there was need for them. At the height of the Celtic Tiger era, these tax provisions pressed the accelerator on the property boom, inflating property prices and encouraging runaway property speculation. Schemes aimed exclusively at people with incomes in excess of €250,000 allowed them to avail of tax breaks on car parks, nursing homes, etc., that could minimise or eliminate their tax bill completely. Famously, Joan Burton TD highlighted in the Dáil the eleven individuals in 2006 earning in excess of a million euro who legitimately reduced their income tax bill to zero due to extensive recourse to tax breaks and shelters. It appeared that in the mind of many, ‘taxes were for the little people’.

Tax Havens and Residency:Many of Ireland’s richest individuals are able, because of their global business interests, to take advantage of residency rules to situate themselves in locations that minimise their tax liabilities.

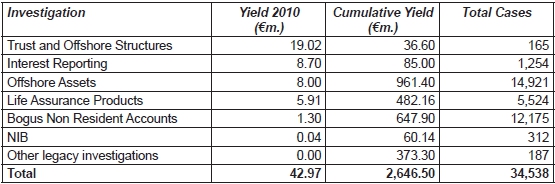

Tax Evasion:During 2010, Revenue Commissioner auditors completed 11,008 audits with an overall yield of €435 million; in the previous year, the yield was €602 million from 12,419 audits.7Since their inception, Revenue special investigations – such as those into the Bogus Non Resident Accounts, Single Premiums, and others – have yielded a total of €2.65 billion in taxes and penalties (see Table 2). As a result of these investigations, 34,538 cases of unpaid or underpaid taxes have been successfully pursued.8

| Table 2: Yields from Revenue Special Investigations |

|

| Source: Revenue Commisioners, Headline Results for 2010 |

Consumption Taxes

Tax on the consumption of goods and services is raised principally from VAT and from Excise and Customs duties. The combined receipts under these two headings stood at €12.1 billion in 2000, rose to a high of €20.8 billion in 2007, and fell to €15 billion in 2010.

VAT receipts yielded €7.5 billion in 2000, grew to a peak of €14.5 billion in 2007 and fell to €10.1 billion in 2010. This trend reflects the consumer boom which developed alongside the huge increase in incomes and wealth during the years of strong economic growth, but which was followed by a significant retrenchment in spending after the downturn in the economy. Excise returns in 2010 stood at €4.7 billion; this was similar to the yield in 2000 (€4.4 billion); in between, however, there was a significant rise, with receipts in 2007 amounting to €6.0 billion.

The fall in Exchequer returns in these categories reflects the erosion of consumer confidence since 2008, and highlights the risk of relying on bumper tax receipts from a consumer spending boom. Budgetary planning needs to reflect the inherent volatility of such taxes.

Corporate Profits

The low corporate tax rate in Ireland has been credited with attracting mobile inward investment to the country and contributing to the economic boom. It remains a cornerstone of Irish economic policy.

The origins of this low rate go back to the 1998 Budget (introduced in December 1997), when the then Minister for Finance, Charlie McCreevy TD, announced plans for a new regime for corporation tax, to be phased in between 1998 and 2003. Under the plan, a series of reductions would see the corporation tax rate fall from 32% in the 1998 financial year to 12.5% from 1 January 2003 onwards.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, the reduction in corporation tax rates led to an increase in yield. This is accounted for, in part, by the ingenuity of the tax planners for multinational companies who can advise these companies on how to utilise transfer pricing and other mechanisms to move profits through branches in Ireland. Even though the Irish-based section might be only a very small element of an international company, these mechanisms to allow profits to be ‘located’ in Ireland for tax purposes can result in a very significant reduction in the company’s tax bill.9

While the low corporation tax rate has undoubtedly been a major factor in enticing multinationals to locate here, with associated economic and employment benefits, Ireland has also incurred reputational damage, especially among its EU partners, as a result of its corporation tax regime.

Capital Gains and Stamp Duty

From 1997 to 2000, the then Minister for Finance, Charlie McCreevy TD, cut the rate of Capital Gains Tax from 40% to 20%. The rate is currently 25%.

The reduction in Capital Gains Tax and the extension of Section 23 tax allowances – measures which were implemented against the advice of the Department of Finance – are generally considered to have contributed significantly to the explosion in housing and commercial property speculation, which ultimately led to the collapse of the Irish banking system.

Revenues from Capital Gains Tax rocketed throughout the period 2002–2007, reflecting an asset bubble in both property and equity prices. The huge losses sustained in recent years mean that revenue from Capital Gains Tax has collapsed despite an increase in rates. Stamp Duty revenues, which also grew in parallel to the property boom, have likewise shown a sharp decline since 2007.

The windfall returns from asset-based tax heads were a significant factor in the Exchequer surpluses from 2003 onwards. But relying on what were fundamentally volatile tax heads to fund increases in public spending was not a sustainable approach, as was starkly revealed when the revenue in these categories fell sharply. That decline has been so precipitous that by 2010 the yield from Capital Gains Tax and Stamp Duty was just 19% of what it had been in 2006.

Other Taxes

A notable feature of the Irish taxation system is what hasnotbeen taxed.

The absence of a property tax or a speculative land tax has not only resulted in the loss of a revenue stream but meant that during the boom years potentially useful instruments for ‘cooling’ the property market could not be used. The removal, by the Fianna Fáil government of 1977–1981, of rates on residential property has had a profound effect on the resourcing of local government in Ireland. The Fianna Fáil/Green Party Coalition Government committed itself to introducing a property tax, extending carbon taxes and introducing water charges; these commitments are reflected in the EU/IMF bailout programme.10

Wealth, as opposed to income, is not taxed. There is likely to be public support for the notion that people who accumulated massive wealth in the boom should pay their fair share in the bust, through a tax on wealth. The Commission on Taxation concluded that while there was merit in a wealth tax the difficulties in definition and collection would outweigh the potential return, and so it came down against the introduction of such a tax.11

Summary of Trends

Returning to Table 1, the significance of the erosion of the income tax base during the Celtic Tiger years was masked by burgeoning receipts from the greatly increased number of people in employment and by runaway returns from an asset and property bubble and a consumer-led spending boom.

The main focus of taxation policy in the budgets since the beginning of the crisis has been to increase tax on income and close the door on property breaks – but long afterthat horse has bolted. In my view, a balance of taxes needs to be achieved between income, capital, spending and other sources such as wealth, property and direct charges. Part of the case for a wealth tax is that it would lead to greater transparency as to the distribution of wealth in this country.

In addition, I believe the tax base needs to be broadened within each tax head. The approach to the taxation of corporate profits needs perhaps to be more pragmatic. The benefits of higher tax rates would likely be outweighed by the negative impact on jobs and growth resulting from a consequent flight of mobile foreign direct investment.

Purposes and Principles

One of the primary purposes of taxation is to fund the operations of the State including:

- ensuring the basic security of the State (for example, the Army and Gardaí);

- maintaining public amenities such as roads, water supplies, public transport, parks and amenities;

- providing public services (for example, social welfare, education, health, and social care services).

A further function of taxation is to contribute to the creation a more equal and fair society through the redistribution of income. In this context, it needs to be remembered that Ireland has one of the most unequal distributions of income among OECD countries.12

The Commission on Taxation highlighted that taxation also has a role in incentivising labour and supporting economic activity which has the potential to sustain and increase employment.13

The payment of taxes is effectively a contract between a citizen or a corporate body and the State. A key principle underlying taxation is equity or fairness: the taxation system should take account of people’s ability to pay the taxes levied and should be informed by the concept of progressivity – those who can afford most, pay the highest taxes. Other key principles are simplicity – the system should be easy to understand and implement – and efficiency.

But an equally important principle is the effective and fair use of taxes – in other words that revenue raised is spent appropriately and transparently.

Waste and the Erosion of Public Trust

From the late 1990s, Ireland was awash with seemingly ever-increasing asset-based revenues (for example, stamp duty returns) and receipts from a boom in consumption. The benefits of our booming economy were felt across every section of the population. Social welfare rates for people of working-age are now more than twice what they were in 2000. Over the same period, the State pension almost doubled. These increases were well ahead of the cost of living. Public service pay also increased significantly: from 2000 to 2009 average public service salaries increased by 59%.

But as public spending increased sharply alongside the increase in tax receipts, there was also very visible and venal waste of taxpayers’ money. This led to frequent statements along the following lines: ‘I wouldn’t mind paying tax – if only so much of it wasn’t being wasted’. There developed a deep-seated lack of public trust that those responsible for allocating and spending the money raised in taxation were falling short in their ‘duty of care’ to respect the money contributed by taxpayers and use it as prudently as if it were their own.

Politicians who failed in their primary duty to safeguard the interests of the country and its citizens, who failed to regulate, who capitulated to vested interests and ultimately wrecked the public finances, awarded themselves massive increases in pay and benefits. In the some quarters, flying first class, staying in five-star hotels, lavish expenses accounts and maximising travel expense claims were deemed to be ‘entitlements’ attaching to elite positions in the political and administrative system. Such behaviour significantly eroded public trust in the political system and in the state sector.

However, this lack of trust has taken on a whole new dimension with the massive bailout of banks and other financial institutions. The recklessness of developers and bankers and the failure of regulators and politicians to ensure adherence to best practice mean that the compliant tax payer is footing an extraordinary bill for risks taken for which they could receive no reward. While the profits of the boom years were privatised, the risk and the burden of adjustment have been well and truly socialised. Any sense of social solidarity with regard to taxation has been trampled into the ground over the past three years.

Ways Forward

The contract between taxpayer and Irish State has been demonstrated to be weak, with strong recourse to tax avoidance measures and a perceived indifference to tax evasion: ‘your only sin is to be caught’. In recent years, this process accelerated with the destruction of public confidence in how tax revenues were being spent.

Invariably, commentators refer to ‘the burden of taxation’ and there has been a failure in public discourse to get beyond this position to understand the potential of taxation to be a ‘moral good’ and a mechanism for social solidarity.14This is reinforced when hard-earned income is taxed more heavily so that banks can be bailed out rather than the money being used to fund the type of quality public services in health, education and welfare that people desire.

The current crisis seems to have precipitated a two-dimensional challenge. The first is the fiscal challenge of restoring stability through broadening the tax base and prudent public spending. The second is a deeper challenge in terms of the values we wish to espouse and the type of society that people in Ireland want to create.

The Fiscal Challenge

In terms of the fiscal challenge, the path forward requires a return to basic principles of sound economic management. The Commission on Taxation in its report identified a number of fundamental issues as informing its approach to the reform of the Irish tax system.

Balance of Taxation:The Commission emphasised the need for ‘an appropriate balance of taxation between income, capital and spending’, and said that in striking the appropriate balance Government should seek ‘to broaden the base within each tax head’ and look to the potential for this in ‘property taxes, spending taxes (especially environmental taxes), and income taxes in that order’.15

Stable Revenue Base:The Commission took the view that the design of the tax system should, as far as possible, seek to eliminate volatility in tax receipts. It added:

A consideration in achieving a stable tax base is to tax those factors that cannot avoid the charge to tax. The most obvious example of this is immovable property … Introducing an annual tax on residential property represents an important step towards providing a stable and non-volatile tax base.16

Equity:The Commission described equity as ‘a key aspect of a tax system’. Noting the role of taxation in the redistribution of income, it pointed out that:

… redistribution occurs not only in the tax system but also through the welfare system and both systems should operate in a coordinated way. Equity should be considered in the context of the overall tax system.17

Sustainable fiscal balance:The Commission highlighted the danger of ‘pro-cyclical’ tax measures which serve to intensify what is occurring in the business and economic cycle. Such measures were, of course, a feature of the Celtic Tiger years, with, on the one hand, tax breaks fuelling the property boom and, on the other, an approach to expenditure summed up in the phrase, ‘when we have it, we spend it’.

The Commission recommended that fiscal policy ‘should pursue a counter-cyclical budgetary approach’, and it went on to say:

Taking into account the position of the economic cycle involves the accumulation of resources in good times so that in less benign times fiscal policy can be expanded in order to support greater economic activity.18

The Challenge in Terms of Values

The difficult choices to be made in order to restore stability to the public finances (choices in relation to both the balance of taxation and how public spending can be reduced) lead inevitably to questions regarding the kind of values we wish to see informing those choices, and thus to the kind of society we want to create in Ireland.

During the Celtic Tiger years, Ireland embraced an economic and social model with an unfettered, unregulated form of capitalism creating massive increases in wealth, high levels of employment and windfall tax revenues. The increased yield from taxation allowed significant growth in spending on public services – but these services were often costly and inefficient.

Ireland sought the impossible: a low tax economyandhigh levels of public provision. The current dire state of the country’s finances inevitably means that a choice has to be made between the two.

The type of value questions and issues that need now to be considered include:

- What kind of society do we want and what is the role of taxation in bringing about that society?

- What kind of public services will the taxation regime we choose allow us to provide?

- How can quality public services be provided in an efficient manner and at an affordable cost?

- If we want a low tax regime in the long term what does that imply for the provision of public services? On the other hand, can sufficient economic growth and resources be generated without a low tax regime?

- How can wealth be generated in a sustainable and regulated manner that takes cognisance of the common good? How can tax policy support this ethical and sustainable wealth generation?

- How do we ensure a system characterised by fairness – a system where people pay in proportion to their ability and where there is a strong commitment to ensuring compliance?

- How do we ensure value for money in the spending of tax receipts – given the reality that there will continue to be public resentment and widespread resistance to taxation if the State fails in its responsibility to regulate effectively and in its duty of care in regard to taxpayers’ money?

- Is there a case for the introduction of a wealth tax – a case that arises not necessarily from the amount of revenue that might be generated but from the symbolic value in terms of social solidarity of such a tax?

- Does Irish society consider taxation as a question only of public policy – is it prepared to see it also as an issue of both personal ethics and the common good?

The answer to these questions – or a failure to address them – will have a profound impact on Irish society for generations to come.

TheCompendium of the Social Doctrine of the Churchis instructive as to the importance of a values based approach to taxation and public expenditure policy:

Tax revenues and public spending take on crucial economic importance for every civil and political community. The goal to be sought is public financing that is itself capable of becoming an instrument of development and solidarity.19

All crises present opportunities as well as challenges. Perhaps the present crisis in Ireland will see the start of a process of creating systems for the collecting and spending of public money that are firmly based on a commitment to social solidarity and to development that is sustainable.

Notes

- Towards Recovery: Programme for a National Government 2011–2016, March 2011, p.16 (www.taoiseach.gov.ie).

- Central Statistics Office, Annual Percentage Change in Consumer Price Index (%) by Year (All Items), data downloaded from www.cso.ie 28 March 2011.

- The National Recovery Plan 2011–2014, Dublin: Stationery Office, 2010, p. 6.

- Financial Statement of the Minister for Finance, Mr Brian Lenihan, T.D., 7 December 2010(www.budget.gov.ie).

- The National Recovery Plan 2011–2014,op. cit.

- Alan Murdock, ‘Irish Run out of Luck for Tax Amnesty’,The Independent, 4 July 1993.

- Revenue Commissioners,Headline Results for 2010andAnnual Report 2009(www.revenue.ie).

- Revenue Commissioners,Headline Results for 2010(www.revenue.ie).

- Laura Slattery, ‘How Google Dines on Double Irish or Dutch Sandwich’,The Irish Times, 25 October 2010.

- EU/IMF Programme of Financial Support for Ireland, 16 December 2010, pp. 25–26.

- Commission on Taxation,Report 2009, Dublin: Stationery Office, 2009, p. 130.

- OECD,Growing Unequal? Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries, Paris: OECD, 2008 (see www.oecd.org/els/social/inequality).

- Commission on Taxation,op. cit., p. 2.

- Polly Toynbee, ‘Taxes are a Moral Good, and Avoiding your Fair Share is a Moral Disgrace’,The Guardian, 15 September 2006 .

- Commission on Taxation,op. cit., p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace,Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, Dublin: Veritas, 2005, n. 355, p. 168.

Eugene Quinn is National Director of the Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland. He worked in the insurance industry as an actuary for twelve years.