Eugene Quinn

Introduction

The Statement of Government Priorities 2014–2016, which was issued by the Fine Gael and Labour Party Coalition Government in July 2014, included a commitment to ‘treat asylum seekers with the humanity and respect that they deserve … [and] reduce the length of time the applicant spends in the system …’.1

This commitment came against a background where the Irish system of Direct Provision for asylum seekers was featuring regularly in the media, with reports from around the country of protests, enforced transfers, hunger strikes and calls for the closure of accommodation centres. The growing concern about the Direct Provision system was encapsulated in a comment by the then Minister of State with special responsibility for New Communities, Culture and Equality, Aodhán Ó Ríordáin TD, who said: ‘None of us can stand over it, it’s just not acceptable’.2

In mid-September 2014, a roundtable consultation was held by the government ministers with responsibility for the operation of the asylum and immigration systems in Ireland to hear the concerns and analyses of NGOs working in the area. Subsequently, in October, the Government established a Working Group which was asked to undertake the first comprehensive review of the protection process, including the Direct Provision system introduced in 2000, and report back to Government with recommendations.3

This article describes the approach of the Working Group, including the consultation process undertaken; the main findings and recommendations put forward in the Working Group’s Final Report, published in June 2015, and the response from Government since then in terms of implementation of key recommendations.

Membership and Mandate

The membership of the Working Group on the Protection Process comprised:

• Representatives of NGOs concerned with asylum and refugee issues – Irish Refugee Council;4 Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland; NASC; SPIRASI; the Children’s Rights Alliance;

• Represenatives of those seeking protection – the Core Group of Asylum Seekers and Refugees;

• A representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR);

• A representative of each of the following statutory bodies: Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner; Refugee Appeals Tribunal; Office of the Attorney General; Health Service Executive; Tusla – Child and Family Agency;

• Representatives from all relevant government departments.

The non-affiliated members of the Group were: Tim Dalton, Dan Murphy and Dr. Ciara Smyth and the Group was chaired by retired High Court judge, Justice Bryan McMahon.5

As noted, one of the NGOs represented on the Working Group was the Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland (henceforth referred to as JRS Ireland). In light of its mission ‘to accompany, advocate and serve’, JRS Ireland has been supporting asylum seekers living in Direct Provision since 2002 and its services now include regular outreach and support to residents of thirteen Direct Provision centres, located in Dublin, Kildare, Portlaoise, Meath, Clare and Limerick.

Terms of Reference

The terms of reference of the Working Group on the Protection Process were:

… to recommend to the Government what improvements should be made to the State’s existing Direct Provision and protection process and to the various supports provided for protection applicants; and specifically to indicate what actions could be taken in the short and longer term which are directed towards:

(i) improving existing arrangements in the processing of protection applications;

(ii) showing greater respect for the dignity of persons in the system and improving their quality of life by enhancing the support and services currently available;

ensuring at the same time that, in light of recognised budgetary realities, the overall cost of the protection system to the taxpayer is reduced or remains within or close to current levels and that the existing border controls and immigration procedures are not compromised.6

Crucially – and, for some, controversially – the terms of reference were restricted to identifying potential improvements to the existing system, thus excluding consideration of alternatives to Direct Provision for the reception and accommodation of people seeking protection in the state.

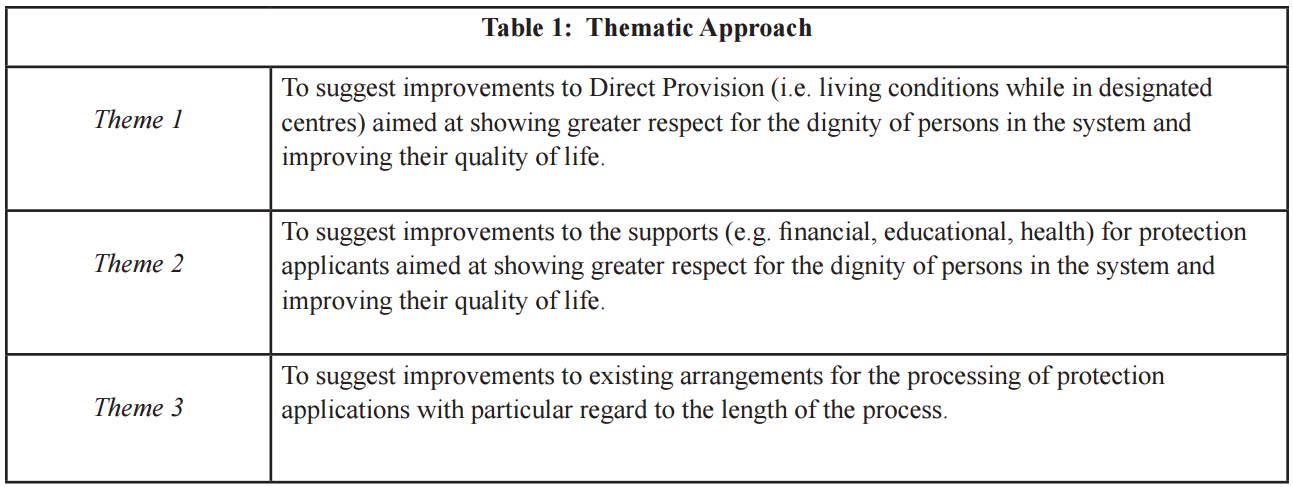

The Working Group adopted a thematic approach, appointing three sub-groups (see Table 1 below).7 These sub-groups met on thirty-eight occasions, submitting recommendations to plenary meetings of the Working Group, which itself met eight times. Deliberations at both levels were informed by academic research, commentary from national and international bodies, submissions from interested parties, the experience of Working Group members and, most importantly, the views of people in the protection process.

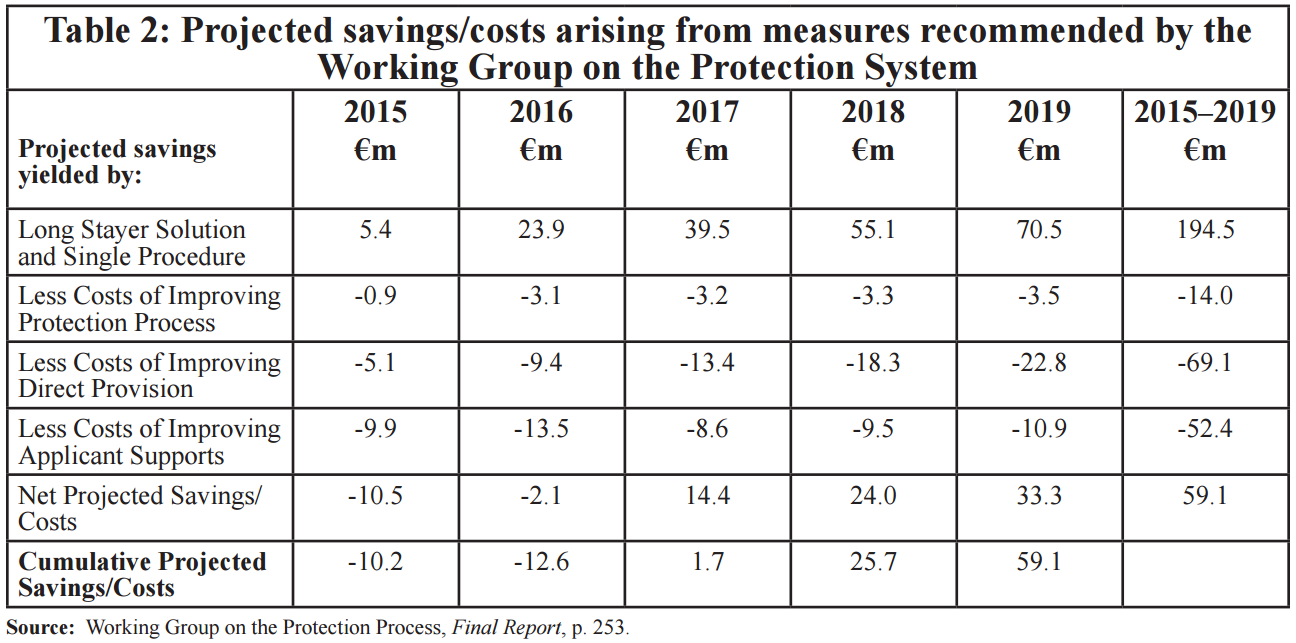

As part of its consideration of proposals for reform, the Working Group undertook a detailed costings exercise, by developing a financial model which projected the overall cost of the protection system, including case processing and costs associated with reception and accommodation in Direct Provision, over a five-year period. Estimates were made of the savings or additional costs expected to arise from the implementation of each recommendation put forward.

Voices of Asylum Seekers

It is self-evident that the voice and experience of asylum seekers should inform any proposals for the improvement of the protection system. The Working Group therefore undertook an extensive consultation process, which involved:

• A call for written submissions from adult and child residents of Direct Provision accommodation centres;

• Ten regional consultation sessions with 381 residents, and visits to fifteen accommodation centres;

• Consultations with particular groups of people in the system, including victims of torture, victims of trafficking and of sexual violence, members of the LGBT community;

• An invitation to participants at the ten regional consultation sessions to nominate a person to make an oral submission to the full Working Group; nine of the sessions nominated a representative.8

The Working Group’s consultations highlighted a wide range of concerns, including many which had previously been the focus of discussion and research: the detrimental impact of the system on mental health;9 the adverse effects on family life;10 inadequacies in relation to the food available to residents in centres, including lack of choice and of access to ethnic food preferences;11 and the prevalence of social exclusion.12

However, the clearest and most consistent message emerging from the consultations was that the principal source of distress and frustration for residents in Direct Provision was the length of time they had to spend in the system.13

One resident noted:

What could be said to be wrong with the system is, in one way or another, directly linked to the length of time spent in it.14

Another said:

Ten years later I still live in the same bed, in the same shared room, of the same direct provision centre – a full decade spent in limbo.15

The significance of the length of time issue, which emerged so clearly in the Working Group’s consultation, was consistent with the experience of JRS Ireland. As outlined in its 2014 Working Paper, No End in Sight – Lives on Hold Long Term in the Asylum Process, the most negative aspects of life in Direct Provision arise from or are exacerbated by the excessive length of time that applicants spend in the system, and include a range of detrimental impacts on children, family life and relationships, the rendering obsolete of skills and qualifications, and the creation of dependency.16

Length of Time Data

To gain a picture of the length of time applicants had been in the system, the Working Group conducted an analysis of data relating to 16 February 2015.

This analysis covered data in respect of applicants in the protection process (that is, persons who have applied for refugee status or subsidiary protection); applicants in the ‘leave to remain’ process (those who have been unsuccessful in their application for protection but whose eligibility for ‘leave to remain’ is yet to be determined); the deportation order stage (where the protection process and ‘leave to remain’ stages have been concluded and a deportation order has been issued); and the judicial review process (where an individual has applied to the courts for judicial review of how their application has been handled).

The analysis of the data for 16 February 2015 showed that there were, in all, 7,937 applicants, of whom 4,350 (almost 55 per cent) had been in the system for over five years. The numbers in the different stages of the application process were as follows:

• 3,876 persons (49 per cent) were in the protection process, of whom almost one-third had been in the system for more than five years;

• 3,343 (42 per cent) were in the ‘leave to remain’ process, of whom three-quarters had been in the system for more than five years;

• 718 (9 per cent) were at the deportation order stage, of whom 88 per cent had been in the system for over five years;

• Approximately 1,000 people from among those in the three groups above were involved in judicial review proceedings. When a person is involved in a judicial review, the further processing of their application is suspended pending the outcome of the review.17

Of the 7,937 applicants, 3,607 (45 per cent) were living in Direct Provision accommodation centres; 1,480 people in this group (42 per cent) had been in the system for more than five years.18

More than half of all applicants (4,330 persons) were living outside Direct Provision; in the case of 66 per cent of this group, five years or more had elapsed since their initial application. Some of the people in this group were believed to have left the state.19

Addressing the Length of Time Issue

In considering the length of time issue, the Working Group took into account a range of matters, including:

• the views of persons in the system;

• the particular situation of children and vulnerable persons;

• the need to deliver efficient and effective solutions that can be easily understood;

• the need to maximise existing resources and the need for additional resources;

• the need to maximise the impact of the solutions proposed on those in the system for lengthy periods; and

• the consequences of the solutions proposed for those in the system, the system itself and the integrity of the protection process.20

The finally agreed recommendation of the Working Group in regard to the length of time question was that the principle be adopted that no person should be in the system for more than five years.21 Essentially, it was recommended that those now in the asylum process for longer than this would be granted a protection status or leave to remain within six months, subject to certain conditions.22 It was estimated that 3,350 people, including 1,480 people living in Direct Provision, would benefit from this proposal.

The Working Group recommended that a start date for the implementation of this solution should be set as soon as possible. It further recommended that at the close of the designated six-month period the authorities should commit to a review of how the solution had operated in practice, and then prioritise the remaining ‘legacy cases’, that is, those of over four years’ duration, then those of over three years’ duration, and so on.

The proposed ‘long stayer’ solution addresses the primary concern articulated by those people for whom the Working Group was established. It is an approach that is likely to be perceived positively by the general public and by several international agencies which, over a number of years, have been critical of Ireland’s asylum system – and, in particular, of the length of time many people spend in that system – and it would thus be a step towards repairing reputational damage. In addition, the implementation of such a measure would be recognition of the reality that in Ireland, as in Europe generally, the majority, if not all, ‘long stayers’ are ultimately never removed from the state’s territory.23

A further consideration is that the exit of those longest in the process would make physical room for new asylum applicants whose arrival is already putting pressure on accommodation resources.24 It would also help create administrative space to enable a smooth transition towards the operation of the long-awaited ‘single procedure’ – that is, a procedure which provides for an integrated assessment of whether an application meets the requirements for being granted refugee status, or subsidiary protection status, or leave to remain, as opposed to a sequential determination process, which requires each stage to be completed before the next can begin.

Recommendations

The Final Report of the Working Group, published on 30 June 2015, set out a total of 173 recommendations which were fully costed.Significantly, each recommendation was ultimately agreed to by all members of the Working Group, including the representatives of government departments and statutory agencies.25 This consensus approach was adopted to effect the removal of any legal or operational barriers to implementation and to facilitate the speedy roll-out of the measures proposed. The Working Group’s key recommendations included:

• Implementation of the proposed ‘long stayer’ solution for people in the system for five years or more.

• Creation of a transition taskforce to support implementation of the ‘long stayer’ solution.

• The enactment of the International Protection Bill and the implementation of the single application procedure as a matter of urgency.

• The inclusion in the International Protection Bill of a right to work for those asylum seekers who are awaiting a ‘first instance’ decision for nine months or more, and who have cooperated with the protection process; this provision should be commenced when the proposed ‘single procedure’ is operating efficiently.

• Increasing the weekly allowance paid to those in Direct Provision from the then current rates of €19.10 for an adult and €9.60 for a child. It was proposed that the rate for an adult should be increased by €19.64. The rationale for this was that, when originally introduced in 2000, the allowance represented 20.83 per cent of the adult rate under Supplementary Welfare Allowance but by 2015 it represented only 10.27 per cent. Restoring the original ratio would mean that the allowance would be set at €38.74 and this was recommended by the Working Group. With regard to the allowance for children, it was recommended that this be increased to €29.80 per child per week, bringing it into line with the sum paid under Supplementary Welfare Allowance in respect of a dependent child. Part of the rationale for the recommended increases was that adults in Direct Provision do not have the right to work and, since 2004, parents are not entitled to receive Child Benefit for dependent children.

• Providing all families with access to cooking facilities (whether in a self-contained unit or through use of a communal kitchen) and their own private living space in so far as practicable.

• Extension of the mandate of the Ombudsman, and of the Ombudsman for Children, to include complaints relating to ‘services provided to residents of Direct Provision centres’, and ‘transfer decisions following a breach of the House Rules’.

• Establishment of a standards-setting committee for Direct Provision accommodation.

It is important to note that the costings exercise undertaken by the Working Group demonstrated that the savings which would arise from resolving the situation of those in the system for five years or more, and from eliminating delays in the determination process, would outweigh the costs associated with implementing the Group’s recommendations for improved living conditions in Direct Provision centres and enhanced supports for protection applicants (see Table 2 below).

Progress in Implementation

‘Long Stayer’ Solution

Since the publication of the Working Group’s report in June 2015, there has been no official statement from Government regarding the Group’s recommendations on the ‘long stayer’ issue. Nevertheless, there appears to be a de facto acceptance at official level of the principle that people should not be in the protection application system for more than five years. This is reflected in an increase in the number of applicants of this duration being granted leave to remain. During 2015, approximately 1,400 people who had been longest in the system had their situation resolved by being given leave to remain – in contrast to just over 700 in 2014.

Despite this progress, it is clear that there still remains a significant challenge to ensure that all those the Working Group estimated would benefit from its ‘long stayer’ solution – a total of 3,350 individuals – will have their situation resolved. This can only be achieved in a timely fashion if the recommended additional resources are provided in full.

It needs to be remembered also that over a year has now elapsed since the date (16 February 2015) in respect of which the Working Group analysed data to establish the length of time applicants had been in the process. The 684 people whose application was then of four years’ duration,26 are now more than five years in the system and are thus eligible for the ‘long stayer’ solution.

Single Procedure

Having been passed by the Oireachtas, the International Protection Bill 2015 was signed into law by President Michael D. Higgins on 30 December 2015 and is expected to be commenced in the latter part of 2016. The Act’s provision for a ‘single procedure’ for processing applications for protection is a significant and welcome development. However, there are grounds for concern that the reformed procedure may not be successful in the key task of expediting the processing of new applications, since the system will have to cope not only with the marked increase in the number of new applications for protection, but will have to take responsibility for transferring over and dealing with cases pending at the time the new system comes into operation.

On 31 December 2015, the Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner (ORAC), the body responsible for making ‘first-instance’ decisions, had 2,582 cases in hand, more than three times the number (743) outstanding at the end of 2014. The median case-processing time doubled during 2015, increasing from 15 weeks to nearly 30 weeks. Yet, during 2015, the number of cases processed to completion by ORAC increased significantly – rising from 1,060 in 2014 to 1,552. The delays in the system reflect the sharp rise in new applications for asylum since 2013, when the total was 946. In 2014, the number of new applications was 1,448, and in 2015 it was 3,276 (that is, an increase of 246 per cent since 2013). In the first two months of 2016, there were 406 new applications. 27

In addition to pending cases in the ‘first instance’ stage of the process (that is, cases being dealt with by ORAC), the new single procedure will also have to deal with outstanding refugee appeal cases from the ‘second instance’ stage. On 11 March 2016, the Refugee Appeals Tribunal, the body responsible for dealing with such cases, had 1,070 appeals pending.28

As of early 2016, therefore, there would be in excess of 3,600 cases (that is, the combined totals from ORAC and the Refugee Appeals Tribunal of cases pending) to be transferred to the new Office of the Chief International Protection Officer. It is imperative that this considerable backlog is fully dealt with prior to the commencement of the single procedure. Otherwise, these cases will have to be transferred over into the single procedure system, with the result that the processing of new applications will be delayed. The inevitable outcome will be the re-emergence under the new system of the excessive delays that have characterised the protection process for well over a decade.

Resources

In September 2015, the Department of Justice and Equality stated in a Press Release that the Government had agreed that ‘an additional budget allocation’ would be made available to deal with demands on the asylum and immigration systems, including ‘backlog cases identified in the recent report of the Working Group on the Protection System’.29

However, the delays in implementing the ‘long stayer’ solution and the evidence of increasing backlogs in the processing system, as outlined above, highlight that there remains a need to greatly enhance the capacity of the various authorities charged with making decisions on protection applications. The Working Group provided an outline of the additional resources required by the decision-making bodies and emphasised that in the absence of extra resources the anticipated benefits of the single procedure in terms of speeding up the processing of applications would not be realised, particularly in a context of growing numbers of new applications.30

As well as highlighting the need for additional resources for the processing system, the Working Group demonstrated that investing in decision-making not only yields benefits in reducing the time spent in the system, but also makes financial sense. Its costings exercise showed that each year a person remains in the system gives rise to accommodation costs of, on average, almost €11,000 per applicant. The cost of decision-making is a fraction of this.31

The principal conclusion is that if the State fails to adequately resource the status determination process it will incur far higher costs in accommodating and supporting applicants over a prolonged period. However, it is asylum applicants and their families who will pay the greatest price, in terms of the long-term human costs of excessive delays in the process.

Transition Task Force

A key issue for people whose application has been successful is the transition from the protection process to becoming part of mainstream Irish society, in terms of accommodation, employment, education, access to services and participation in community life. The Working Group noted that different groups (for example, those granted status after spending years in the system and those relatively newly arrived in Ireland whose application may be processed more speedily under the new single procedure) will face different transition issues and have different needs.

The Working Group recommended that, as a matter of priority, the Minister of State for New Communities, Culture and Equality ‘should convene a taskforce of cross-departmental representatives, State agencies and relevant NGOs’ to address the wide range of transition needs of those granted status, warning that ‘in the absence of a consistent plan for the legacy group, in particular, they may not be able to leave Direct Provision’.32

In July 2015, the Minister of State announced the establishment of a Government Task Force to examine the transition needs of those who had been given protection status but continued to live in Direct Provision.33 The Transition Task Force has published a guide to living independently and has developed information sessions on transition to be delivered to Direct Provision residents who have been granted status.

Against the backdrop of a national housing crisis, securing accommodation remains the greatest problem facing people who, having obtained status, are entitled to leave Direct Provision accommodation. In a submission to the Transition Task Force, JRS Ireland advocated that there should be more structured support in regard to housing for this group, and recommended the adoption of the Homeless Action Team model as an appropriate template for assisting vulnerable long-term residents exiting Direct Provision.34 To date, the Task Force has not recommended that specialised support in regard to finding suitable accommodation in the community be offered to people with status exiting Direct Provision.

Right to Work

As already noted, the Working Group recommended that applicants for protection should be able to access the labour market if still awaiting a decision after nine months, once the single procedure was operating effectively. A particularly disappointing feature of the International Protection Act 2015 is the fact that it does not include any provision in respect of this issue. Ireland therefore remains the only Member State of the EU, apart from Lithuania, which does not provide for a right to work at any stage during the application process.35

Direct Provision Conditions and Supports

Regrettably, key recommendations of the Working Group regarding conditions in Direct Provision centres – namely, access to cooking facilities and additional living space for families – have not been implemented. The increase in new applications during 2015, combined with the slow rate of implementation of the ‘long stayer’ solution, have placed pressure on bed spaces and resulted in new Direct Provision centres being opened. In January 2016, the Government announced the first increase in the Direct Provision weekly payment since its introduction in 2000. The allowance for each child was raised by €6.00 to a rate of €15.60 per week, but this is far short of the rate of €29.80 recommended by the Working Group.36 The adult weekly allowance has not been increased, however, and so remains at €19.10.

As already noted, one of the recommendations of the Working Group was that the mandate of the Ombudsman, and of the Ombudsman for Children, should be extended to include complaints from residents in Direct Provision. In February 2016, the holders of the two Ombudsman offices issued a public statement welcoming the Minister for Justice’s ‘commitment in principle’ to extend their remit.37 It is vital that the measures necessary to implement this commitment will be put in place at the earliest opportunity.

An inflatable boat filled with refugees and other migrants approaches the north coast of the Greek island of Lesbos. Turkey is visible in the background. More than 500,000 migrants have crossed by boat from Turkey to the Greek islands so far in 2015.

Migrants in inflatable boat between Turkey and Greece October 2015 iStock Photo ©Joel Carillet

Conclusion

The announcement by the Government in 2014 that it was establishing a Working Group to undertake a systematic review of the protection process, including the system of Direct Provision, was a significant first step towards reform of an area of public policy that had become the subject of increasing concern.

The Working Group was unanimous in its opinion of the importance and urgency of taking action to resolve the situation of thousands of people, a third of them children, living in limbo for years in the protection application system. It put forward fully-costed recommendations, which respected existing immigration and border controls, to address this.

Equally, it emphasised the need to ensure that lengthy backlogs do not again develop in the system. It stressed too the importance of taking immediate steps to improve living conditions and supports for people in Direct Provision centres.

Since the Working Group reported in June 2015 there has been progress with regard to resolving the situation of those whose applications have been longest in the system, although considerable work remains to be done. In addition, long-awaited legislation to underpin reform of the protection process has been enacted in the International Protection Act 2015. Obviously, these are welcome developments. However, there is also emerging a picture of increased delays and backlogs in dealing with applications at the earlier stages of the process. This reflects a significant increase in new applications since 2013. It also reflects a failure to allocate the level of additional resources identified by the Working Group as necessary to enable the full and speedy implementation of an appropriate solution for those longest in the system and to address processing backlogs.

A failure to implement the key recommendations in the Working Group’s report will mean that the lengthy waiting times and the unsuitable living conditions which prompted the establishment of the Working Group will continue. Above all, a failure of implementation will inevitably impose heavy costs on the individuals, families and children living for prolonged periods in Direct Provision centres. The toll of spending years with ‘no end in sight’ was summed up in a comment made by one protection applicant during the Working Group’s consultation: ‘As we kill the time, the time kills us’.

In light of the evidence from protection applicants assembled by the Working Group during its consultations, and given that all its members, including representatives of government departments and statutory agencies, agreed to the Group’s final report, there are no justifiable reasons for delaying the implementation of its key recommendations. The time to act is now.38

Notes

1. Department of the Taoiseach, Statement of Government Priorities 2014–2016, Dublin, 2014. (http://www.taoiseach.gov.ie/eng/Work_Of_The_Department/Programme_for_Government/)

2. Christian Finn, ‘“Direct Provision”: None of us can stand over it, it’s just not acceptable’, thejournal.ie, 23 July 2014. (http://www.thejournal.ie/direct-provision-reform-1586753-Jul2014/)

3. Department of Justice and Equality, ‘Ministers Fitzgerald and O Ríordáin announce composition of Working Group to examine improvements to the Protection process and the Direct Provision system’, Press Release, 13 October 2014. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/PR14000280)

4. Sue Conlan, CEO, Irish Refugee Council tendered her resignation from the Working Group as of 26 March 2015.

5. Working Group to Report to Government on Improvements to the Protection Process, including Direct Provision and Supports to Asylum Seekers, Final Report, Dublin: Department of Justice and Equality, 2015, p. 28. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/Report-to-Government-on-Improvements-to-the-Protection-Process-including-Direct-Provision-and-Supports-to-Asylum-Seekers)

6. Ibid., p. 12.

7. Ibid., par. 11, pp. 29–30. See also Appendix 2, ‘Membership of the Thematic Sub-groups’, pp. 262–64.

8. Ibid., par. 19, p. 15.

9. Magzoub Toar, Kirsty K. O’Brien and Tom Fahey, ‘Comparison of Self-Reported Health and Healthcare Utilisation between Asylum Seekers and Refugees: An Observational Study’, BMC Public Health, 2009, 9: 214.

10. Samantha K. Arnold, State Sanctioned Child Poverty and Exclusion – The Case of Children in State Accommodation for Asylum Seekers, Dublin: Irish Refugee Council, 2012.

11. Keelin Barry, What’s Food Got to Do With It: Food Experiences of Asylum Seekers in Direct Provision, Cork: NASC, The Irish Immigrant Support Centre, 2014.

12. Ruth McDonnell, ‘Social Exclusion and the Plight of Asylum Seekers Living in Ireland’, Socheola, Limerick Student Journal of Sociology, Vol. 1, Issue 1, 2009.

13. Working Group on the Protection Process, Final Report, par. 213, p. 59; par. 3.3, p. 64; see also Appendix 3, pp. 270–72.

14. Ibid., par. 2.12, p. 59.

15. Ibid., Appendix 3, p. 272.

16. See: Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland, No End in Sight – Lives on Hold Long Term in the Asylum Process, Dublin: JRS Ireland, 2014. (http://www.jrs.ie)

17. Working Group on the Protection Process, Final Report, par. 3.8, pp. 65–6.

18. Ibid., pars. 3.10–3.11, p. 66.

19. Ibid., par. 3.13, p. 66.

20. Ibid., par. 3.125, p. 86.

21. Ibid., par. 25, p. 16; par. 3.126, p. 86.

22. These conditions are outlined in the Report of the Working Group, pars. 3.129–3.130, p. 87.

23. In reports in 2007 and 2010, the Jesuit Refugee Service Europe highlighted the phenomenon of non-returnable forced migrants, including unsuccessful asylum seekers, who had exhausted all avenues for obtaining a legal right to remain. See: We are Dying Silent: Report on Destitute Forced Migrants, Brussels, JRS Europe, 2007; Living in Limbo – Forced Migrant Destitution in Europe, Brussels: JRS Europe, 2010.

24. Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner, Monthly Statistical Report, January 2016. (http://www.orac.ie)

25. The government departments concerned were: Department of Justice and Equality; Department of Public Expenditure and Reform; Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government; Department of Social Protection; Department of Children and Youth Affairs; Department of Education and Skills. The statutory agencies were: Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner; Refugee Appeals Tribunal; Office of the Attorney General; HSE; Tusla – Child and Family Agency.

26. Working Group on the Protection Process, Final Report, Appendix 6, Table 1, p. 350.

27. Office of the Refugee Applications Commissioner, Monthly Statistical Report, February 2016. (http://www.orac.ie)

28. Information provided by the Refugee Appeals Tribunal on 14 March 2016, in response to a request under the Freedom of Information Act 2014.

29. Department of Justice and Equality, ‘Government approves ‘Irish Refugee Protection Programme’’, Press Release, 10 September 2015. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/PR15000463)

30. Working Group on the Protection Process, Final Report, par. 6.41, pp. 255–56.

31. Ibid., par. 6.45, p. 256.

32. Ibid., pars. 5.169–170, p. 239.

33. Department of Justice and Equality, ‘Minister of State Ó Ríordáin to chair Taskforce established by Government to assist with transition of persons from Direct Provision’, Press Release, 16 July 2015. (http://www.justice.ie/en/JELR/Pages/PR15000418)

34. JRS Ireland, Submission to the Transition Taskforce, ‘Leaving Direct Provision: Assisting Persons with Status Transition to Independent Living’, August 2015.

35. Working Group on the Protection Process, Final Report, par. 535, p. 209.

36. See: Mags Gargan, ‘Child Direct Provision payment increase ‘paltry’’, The Irish Catholic, 14 January 2016.

37. ‘Commitment to allowing residents in Direct Provision to make complaints to Ombudsman offices welcomed’, Press Release issued jointly by the Ombudsman for Children and the Office of the Ombudsman, 4 February 2016. (https://www.ombudsman.gov.ie/en/News/Media-Releases/2016-Media-Releases/Direct-Provision-complaints.html)

38. Six groups which were represented on the Working Group have come together to campaign for the implementation of the key recommendations of the Working Group’s Final Report. These groups are: Core Group of Asylum Seekers; Children’s Rights Alliance; JRS Ireland; NASC; SPIRASI; UNHCR. They have established a website, ‘Time to Act’, which enables organisations to endorse the call for action to implement the recommendations of the Working Group (http://www.timetoact.ie/).

Eugene Quinn is Director of Jesuit Refugee Service Ireland and was a member of the Working Group on the Protection Process.